Learning Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MS 5110 National Aboriginal Conference, National Office And

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 5110 National Aboriginal Conference, National Office and Resource Centre records, 1974-1975, 1978-1985 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY .......…………………………………………………....…........ p.3 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT ……………………………………........... p.3 ACCESS TO COLLECTION .………………………………...…….……………….......... p.4 COLLECTION OVERVIEW ………...……………………………………..…....…..…… p.5 ADMNISTRATIVE NOTE …............………………………………...…………........….. p.6 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................... p.7 SERIES DESCRIPTION ………………………………………………………..……….... p.8 Series 1 NAC, National Executive, Meeting papers, 1974-1975, 1978-1985 p.8 Subseries 1/1 National Aboriginal Congress, copies of minutes of meetings and related papers, 1974-1975 ................................................ p.8 Subseries 1/2 National Aboriginal Conference, Minutes of meetings and related papers, 1979-1985 ......................................................... p.9 Subseries 1/3 National Aboriginal Conference, Resolutions and indexes to resolutions, 1978-1983 .............................................................. p.15 Subseries 1/4 Department of Aboriginal Affairs, Portfolio meeting papers, 1983-1984 .................................................................................. p.16 Series 2 NAC, National Office, Correspondence and telexes, 1979-1985.... p.20 Subseries 2/1 Correspondence registers, 1983-1985 ………………………… p.20 Subseries -

Dapto High School

DAPTO HIGH SCHOOL Legal Studies Preliminary and HSC Courses MEDIA FILE Media Articles for use in course information, referencing in essay responses and study material. CONTENTS Sources and Framework of International Law Australia will sign UN charter on indigenous rights: Dodson 4 Federal law aims to stop death penalty 5 Operation of the legal system in relation to native title Native title to be presumed in proposed law reforms 6 Victoria revamps native title 7 Native title claimants die before justice done 8 A few home truths, after Mabo 9 Power and Authority Bikie laws sideline the rule of law 10 Legal controls on state power Endangered Animal – charity worker biker now in firing line 11 Men of colours stand united in face of bikie bill 12 Duties GP hid abuse, niece alleges 13 Rights Bikie laws a threat to rights, says Cowdery 14 Focus Group: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples $525,000 - the price of one stolen life 15 Tasmania pays $5m to stolen generations 16 Activists say intervention must be reviewed 17 Labor acts to close Aboriginal health gap 18 Howard years a dark age for progress: Labor 19 Anger reigns in a place shamed before the world 20 Between the Rock and a hard place 21 A long, slow detour in the Northern Territory 22 Promises galore, but change slow to come 23 End culture of racism, says UN inspector 28 UN finds ray of hope in ‘racist’ Australia 29 Focus Group: Women Women stretched to snapping point 30 Pay rises skipping female workers 31 Women pay dearly as earnings gap widens 32 Gender pay gap ‘should be declared’ 33 Women urged to sue to fix pay gap 34 Crime Boy on trial for railway death 35 Bail a fine balancing act by beaks 36 Police may win power to veto bail orders 37 New bail laws- presumption of innocence is the victim 38 2 Contents cont.. -

To Nuclear Waste

= FREE April 2016 VOLUME 6. NUMBER 1. TENANTSPG. ## HIT THE ROOF ABOUT REMOTE HOUSING FAILURE BIG ELECTION YEAR 2016 “NO” TO NUKE DUMP CRICKETERS SHINE P. 5 PG. # P. 6 PG. # P. 30 ISSN 1839-5279ISSN NEWS EDITORIAL Land Rights News Central Australia is published by the Central Land Council three Pressure rises as remote tenants take government to court times a year. AS A SECOND central The Central Land Council Australian community has 27 Stuart Hwy launched legal action against the Northern Territory Alice Springs government and an Alice NT 0870 Springs town camp is following tel: 89516211 suit, the Giles government is under increasing pressure to www.clc.org.au change how it manages remote email [email protected] community and town camp Contributions are welcome houses. Almost a third of Papunya households lodged claims for compensation through SUBSCRIPTIONS the Northern Territory Civil Land Rights News Central Administrative Tribunal in Australia subscriptions are March, over long delays in $20 per year. emergency repairs. A week later, half of the LRNCA is distributed free Larapinta Valley Town Camp Santa Teresa tenant Annie Young says the state of houses in her community has never been worse. to Aboriginal organisations tenants notified the housing and communities in Central department of 160 overdue water all over the front yard, sort told ABC Alice Springs. “Compensation is an Australia repairs, following a survey of like a swamp area,” Katie told “There’s some sort of inertia entitlement under the To subscribe email: by the Central Australian ABC. Some had wires exposed, or blockage in the system that [Residential Tenancies] Act,” [email protected] Aboriginal Legal Aid Service air conditioners not working, when tenants report things he told ABC Alice Springs. -

Barunga Agreement Signed

FREE August 2018 VOLUME 8. NUMBER 2. BARUNGA AGREEMENT SIGNED P. 6 NATIVE TITLE NEW CDP PENALTIES OUTSTATION PROJECT CONSENT DETERMINATIONS THREATEN JOBSEEKERS KICKS OFF P. 9 PG. # P. 5 PG. # P. 4 ISSN 1839-5279ISSN NEWS EDITORIAL Barunga Agreement signed, hard work on treaty begins Land Rights News Central Australia is published by the THE four Northern Territory Central Land Council three land councils made history times a year. at Barunga for the second time on June 8, when they The Central Land Council signed an agreement to start 27 Stuart Hwy working towards a treaty Alice Springs between the NT government NT 0870 and Aboriginal Territorians. tel: 89516211 “This is a momentous day in the history of the www.clc.org.au Territory, a chance to reset email [email protected] the relationship between the Contributions are welcome Territory’s First Nations and the government,” Northern Land Council chair Samuel Bush-Blanasi said. SUBSCRIPTIONS Mr Bush-Blanasi said the Barunga Agreement Land Rights News Central “gives us high hopes about Australia subscriptions are the future and I hope the $22 per year. government stays true to the It is distributed free of spirit” of the memorandum of charge to Aboriginal understanding (MoU). organisations and The Barunga Agreement communities in Central comes 30 years after NT Central Land Council deputy chair Sammy Butcher signs the Barunga Agreement. Australia. Aboriginal leaders delivered the Barunga Statement to then but we don’t want to stay the On the morning before The next step along this To subscribe email prime minister Bob Hawke only players in this game. -

The Gweagal Shield SARAH KEENAN Birkbeck University of London

NILQ 68(3): 283–90 The Gweagal shield SARAH KEENAN Birkbeck University of London The Gweagal shield © Trustees of the British Museum † Abstract When British naval officer James Cook first landed on the continent now known as Australia in April 1770, he was met by warriors of the Gweagal nation whose land he was entering uninvited. The Gweagal were armed with bark shields and wooden spears. Cook fired a musket at them, hitting one. The shield from that first encounter, complete with musket hole, is today displayed in the British Museum. It is subject to a repatriation request from Gweagal man Rodney Kelly, who wishes the shield to be displayed in Australia where Aboriginal people will be able to care for and view it. In this article, I outline the contested legal status of the shield. Centring Kelly’s perspective, I argue that, regardless of whether he is able to prove the precise genealogy of either the shield as object or himself as owner, as an Aboriginal man he has a better claim to the shield than the British Museum. What is at stake in the dispute between Kelly and the British Museum is not just rights over the shield but also the broader issue of basic colonial reparations: in this instance returning an Aboriginal object to Aboriginal control. The issue of ownership/possession of the Gweagal shield cannot be separated from the historical reality of Britain’s mass theft of Aboriginal land, decimation of Aboriginal people and destruction of Aboriginal culture. Keywords: Gweagal shield; property; colonialism; repatriation; Aboriginal Australia. -

The Dancing Trope of Cross-Cultural Language Education Policy | Janine Oldfield and Vincent Forrester 64

The dancing trope of cross-cultural language education policy | Janine Oldfield and Vincent Forrester 64 The dancing trope of cross-cultural language education policy Janine Oldfield Vincent Forrester Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Mutitjulu Elder Education [email protected] [email protected] Keywords: Decolonising research, Indigenous methodologies, Indigenous research methods, culturally responsive research Abstract The language education policy research based on the views of remote Indigenous communities that is the subject of this paper involved a complex metaphoric dance but one centred on the lead of Aboriginal collaborative research participants. The researchers in this dance, fortunately, had enough experience in traditional Aboriginal decision-making processes and so knew the tilts and sways that ensured the emergence of a reliable picture of remote Indigenous knowledge authority. However, as with most Indigenous research, the de-colonisation process and the use of Indigenous research methods hit a misstep when it came to the academy’s ethical procedures and institutional gatekeeping. This almost led to a position from which the research would not recover and from which a contentious but important Indigenous topic on Indigenous language education remained unvoiced. Introduction The introduction of the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER) in 2007 resulted in a set of sweeping changes to remote communities such as the suspension of their human rights; forced acquisition and management of their assets, land and housing; and income management (Altman & Russell, 2012). This ensured a dramatic reduction in self-determination, school attendance, employment and employment prospects but an increase in violence, suicides and social dysfunction (Altman, 2009; Oldfield, 2016). -

Aussie Magician Raising Funds to Perform the Biggest Illusion in the World: Making Uluru Vanish and Reappear EMBARGOED: NOVEMBER 16, 2019

Aussie magician raising funds to perform the biggest illusion in the world: Making Uluru Vanish and Reappear EMBARGOED: NOVEMBER 16, 2019 Sydney magician Dave Welzman , aka ‘Dave Legend,’ has today revealed plans to stage one of the largest illusions ever attempted - making Australia’s most famous monolith, Uluru, vanish and reappear in the " Goodbye Ayers Rock, Hello Uluru " show. The illusion, which has the support of Uluru’s Traditional Owners, the Anangu, will see Ayers Rock ‘disappear’ and Uluru ‘reappear’ before the eyes of a lucky audience . Welzman’s illusion will take place early next year, and forms the pinnacle of the Screen Australia supported documentary, Uluru & The Magician, which releases in cinemas in 2020. If successfully funded, Welzman's illusion will challenge David Copperfield - the current Guinness World Record-holder for the ‘Largest Illusion Ever Staged'. Copperfield famously made New York’s Statue of Liberty Vanish in 1983. The documentary will follow Welzman’s journey, as a Sydney magician who learns from Uluru's Traditional Owners, then creates a magical show to celebrate the profound cultural significance of Uluru, on a grand scale witnessed in magic’s heyday. Collaborating with Luritja Elder, Vincent Forrester , Welzman aims to promote the Anangu's message that Uluru is a sacred place to respect - and to seek the answers to some of life’s big topics along the way, like spirituality vs. the internet, illusion vs. belief and capitalism vs. community. “When I tell people my plans to make Uluru disappear using magic, I’m often faced with the same shocked, slightly puzzled reaction,” Welzman said. -

Annual Report 2016–17

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT 2016–17 CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms and where otherwise noted, all material presented in this report is provided under a http://creativecommons.org/licences/byl3.0/licence. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/byl3.0/legalcode. The document must be attributed as the Central Land Council Annual Report 2016–17. Third party copyright for publications This organisation has made all reasonable effort to: • clearly label material where the copyright is owned by a third party • ensure that the copyright owner has consented to this material being presented in this publication. ISSN 1034-3652 All photos Central Land Council, unless otherwise credited. 20 September 2017 Senator Nigel Scullion Minister for Indigenous Affairs Senate Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister In accordance with the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, the Native Title Act 1993 and the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, I am pleased to approve and submit the 2016-17 Annual Report on the operations of the Central Land Council. I am authorised by the Central Land Council to state that the Accountable Authority is responsible under section 46 of the PGPA Act for the preparation and content of the report. Yours faithfully Mr Francis Kelly Chair Central Land Council CLC ANNUAL REPORT 2016–17 1 OVERVIEW OF THE CLC Chair’s report -

Spring 2019 a Publication of South Australian Native Title Services

Aboriginal Way www.nativetitlesa.org Issue 76, Spring 2019 A publication of South Australian Native Title Services Above: Anangu travelled from communities around Uluru for Inma to celebrate the close of the climb. Anangu celebrate climb close The gate to the climb at Uluru has now Tijangu Thomas, an Anangu Park Ranger honouring the old people and so many “The reason for getting the land right closed permanently and hundreds was also there at the base of the climb and of them have passed away now” he said. back was to close the climb because of Anangu from communities across explained some of the emotion of the day. it’s a sensitive area and the previous Tourists have been consistently climbing Central Australia have gathered to people who’ve passed away, the “Its rather emotional, having elders who Uluru since 1963 when a climbing celebrate the historic moment of traditional owners were suffering and picked up this long journey before I was chain was drilled into the rock without self-determination. ended up being distressed because born, to close the climb. And now they’re consultation with Anangu. they treading on a important place The gate was shut at 4pm on Friday no longer here but we’re carrying on their and disrespectful” he said. 25 October, to remain closed from the legacy to close the climb” he said. In recent weeks the numbers of visitors permanent close date of Saturday 26 climbing the rock has increased with On the day of the permanent close, Sammy Wilson, past Chair of the Uluru- October, which came on the anniversary of tourists flocking to make the climb before Tjulapai Carroll said that anyone visiting Kata Tjuta National Park and Chair of the the day ownership of the Uluru-Kata Tjuta the closure. -

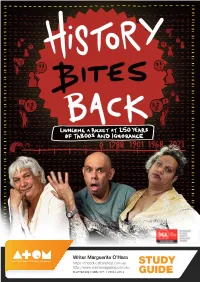

Click Here to Download a PDF of the ATOM Study Guide for HISTORY BITES BACK

Writer Marguerite O’Hara https://theeducationshop.com.au STUDY http://www.metromagazine.com.au © ATOM 2021 ISBN: 978-1-76061-416-4 GUIDE Aboriginal filmmaker Trisha Morton- Thomas (Destiny Does Alice, Occupation: Native) teams up again with Comedy Director/Writer, Craig Anderson (Black Comedy, Occupation: Native), and some of Australia’s freshest comedic talent (Steven Oliver and Elaine Crombie) to bite back at negative social media comments and steer the conversation to look into the historical context of the fortunes and misfortunes of Aboriginal Australians from social security, citizenship and equal wages to nuclear bombs and civil actions. Extras on location - Telegraph Station SYNOPSIS History Bites Back is the antidote to the boring, faceless and overly sincere docos that often populate Indigenous issues. It’s comical, self-aware, and not afraid to launch a rocket into taboo issues. Our continent has over a hundred thousand years of black history but when the whitefellas began to build their country on top of Aboriginal mob’s countries, they believed that the Aboriginal people would die out. Luckily, they were wrong, but ever since then the whitefellas haven’t really known what to do with the blackfellas and the blackfellas haven’t been able to get rid of the whitefellas. Content hyperlinks ….and now there’s other fellas, biggest mob of fellas from Telling the story 3 all over the world sharing this place called Australia. Still, our schools concentrate on the last 250 odd years of Themes 3 colonisation and most of that through a white colonial lens. The Directors’ Statements 4 So, in this day of modern technology, unlimited information and the World Wide Web, Aboriginal people still put up Curriculum Guidelines 5 with a boatload of ignorance and misconceptions from our fellow Australians. -

JULY 2012 Clarion

CLArion No 1207 – 01 July 2012 Email newsletter of Civil Liberties Australia (A04043) Email: Secretary(at)cla.asn.au Web: http://www.cla.asn.au/ Airport scanners set to embarrass breast/gender groups ‘Porn’ on the 1st of July...just to keep our American friends happy Full body scanners which start operating at Australian airports this 1 July will identify prosthesis wearers, including breast cancer survivors, and transgender passengers. Earlier this year the federal government announced that the new scanners to be installed in eight international terminals would show only a generic stick figure image to protect passengers' privacy. But documents released under FOI show that, in meetings with stakeholders, Office of Transport Security representatives confirmed the machines would detect passengers wearing a prosthesis. Breast Cancer Network Australia has alerted its 70,000 members that prosthesis wearers should carry a letter from their doctor and speak to security staff before passing through the body scanner to ensure discreet treatment. While breast implants would not be detected, prosthetic breasts used by those who have had a mastectomy will be. During the meetings, OTS officials confirmed the situation would also apply to transgender passengers, the SMH reported. http://tiny.cc/xs5pfw The scanners – forced on the Australian Government by the US Administration – won’t achieve their aim, which is to stop a copycat “underwear” bomber. “They are simply impractical and literally a waste of time, as well as being privacy-invasive,” CLA’s CEO Bill Rowlings said. “Nobody, not even the Australian Dept of Transport, believes these scanners will make people feel safer and more comfortable. -

November 2005 Newsletter

The Newsletter of the Australian–American Fulbright Commission promoting educational and cultural exchange between Australia and the United States. TheFulbrighterA ustra l ia brilliant scientist, was the intended recipient U.S. Fulbright Scholars of my award? land in the Capital “The Enrichment Seminar was the perfect beginning to my time in Australia. They Nine newly arrived U.S. Fulbright [Commission staff] made clear what an Scholars descended on Canberra in honour it was to be a Fulbright Scholar and August for the sixth Enrichment Seminar. made us all feel special. They drove 650 kms from Melbourne, jetted I returned to Melbourne invigorated and excited 3930 kms across the desert and hung-up their to begin my Fulbright experience down-under.” diving equipment in the Great Barrier Reef to Per Henningsgaard added, “I was delighted attend the Enrichment Seminar in Canberra. to hear of the variety of projects that were The Enrichment Seminar for the 2005 U.S. being pursued, as well as the passion that Fulbright Scholars was changed from each of my fellow Fulbright Scholars brought February to August to bring together the to their particular field. scholars in the earliest part of their Fulbright We were honoured at a dinner hosted by the year. Nine of the twenty U.S. Fulbright ACT Fulbright Alumni at the Axis Restaurant Volume 18 NUmber 3 NovEmber 2005 Scholars attended the Enrichment Seminar in the National Museum of Australia and and formed friendships and networks. Further received Fulbright pins from Susan Crystal, events will welcome other U.S. Fulbright Counselor for Public Affairs, U.S.