The Tipaimukh Dam, Ecological Disasters and Environmental Resistance Beyond Borders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stratified Random Sampling - Manipur (Code -21)

Download The Result Stratified Random Sampling - Manipur (Code -21) Species Selected for Stratification = Cattle + Buffalo Number of Villages Having 100 + (Cattle + Buffalo) = 728 Design Level Prevalence = 0.126 Cluster Level Prevalence = 0.03 Sensitivity of the test used = 0.9 Total No of Villages (Clusters) Selected = 85 Total No of Animals to be Sampled = 1785 Back to Calculation Number Cattle of units Buffalo Cattle DISTRICT_NAME BLOCK_CODE BLOCK_NAME VILLAGE_NAME Buffaloes Cattle + all to Proportion Proportion Buffalo sample Bishnupur 2 Bishnupur Potsangbam And Upokpi 19 253 272 303 20 1 19 Bishnupur 15 Kumbi Kumbi (NP) - Ward No.3 32 296 328 328 20 2 18 Bishnupur 2 Bishnupur Nachou 0 704 704 726 21 0 21 Nambol (M Cl) (Part) - Bishnupur 29 Nambol 15 1200 1215 1222 21 0 21 Ward No.15 Chandel 3 Chakpikarong Charoiching 1 105 106 129 19 0 19 Chandel 24 Machi Laiching Minou 5 113 118 118 19 1 18 Chandel 51 Tengnoupal A.Khullen 0 124 124 124 19 0 19 Chandel 4 Chandel Khudei Khunou 14 114 128 145 19 2 17 Chandel 4 Chandel New Chayang 0 173 173 173 20 0 20 Chandel 24 Machi Laiching Khunou 17 165 182 216 20 2 18 Chandel 24 Machi M.Ringpam 0 190 190 190 20 0 20 Chandel 24 Machi Konaitong 0 196 196 196 20 0 20 Chandel 24 Machi Khunbi 0 222 222 222 20 0 20 Chandel 24 Machi Heinoukhong 0 249 249 249 20 0 20 Chandel 3 Chakpikarong Khullenkhallet 111 140 251 314 20 9 11 Chandel 4 Chandel Beru Khudam 0 274 274 274 20 0 20 Chandel 24 Machi Laiching Kangshang 0 308 308 414 20 0 20 Churachandpur 46 Singngat Tuikuimuallum 4 116 120 120 19 1 18 Churachandpur -

District Census Handbook Senapati

DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK SENAPATI 1 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK SENAPATI MANIPUR SENAPATI DISTRICT 5 0 5 10 D Kilometres er Riv ri a N b o A n r e K T v L i G R u z A d LAII A From e S ! r Dimapur ve ! R i To Chingai ako PUNANAMEI Dzu r 6 e KAYINU v RABUNAMEI 6 TUNGJOY i C R KALINAMEI ! k ! LIYAI KHULLEN o L MAO-MARAM SUB-DIVISION PAOMATA !6 i n TADUBI i rak River 6 R SHAJOUBA a Ba ! R L PUNANAMEIPAOMATA SUB-DIVISION N ! TA DU BI I MARAM CENTRE ! iver R PHUBA KHUMAN 6 ak ar 6 B T r MARAM BAZAR e PURUL ATONGBA v r i R ! e R v i i PURUL k R R a PURUL AKUTPA k d C o o L R ! g n o h k KATOMEI PURUL SUB-DIVISION A I CENTRE T 6 From Tamenglong G 6 TAPHOU NAGA P SENAPATI R 6 6 !MAKHRELUI TAPHOU KUKI 6 To UkhrulS TAPHOU PHYAMEI r e v i T INDIAR r l i e r I v i R r SH I e k v i o S R L g SADAR HILLS WEST i o n NH 2 a h r t I SUB-DIVISION I KANGPOKPI (C T) ! I D BOUNDARY, STATE......................................................... G R SADAR HILLS EAST KANGPOKPI SUB-DIVISION ,, DISTRICT................................................... r r e e D ,, v v i i SUB-DIVISION.......................................... R R l a k h o HEADQUARTERS: DISTRICT......................................... p L SH SAIKUL i P m I a h c I R ,, SUB-DIVISION................................ -

In the High Court of Manipur at Imphal Writ Petition(C) No

1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF MANIPUR AT IMPHAL WRIT PETITION(C) NO. 943 OF 2014 Mr. Guangbi Dangmei, aged about 58 years, s/o late Kakhuphun, a resident Of Longmai/Noney Bazar, Nungba Sub-Divn BPO & PS Noney,Tamenglong District, Manipur. ...Petitioner. Versus 1. The Union of India through the Defence Secretary, Ministry of Defence, Govt. Of India, Central Secretariat, South Block, New Delhi-110011. 2. The Commanding Officer, 10 Assam Rifles, c/o 99 APO 3. The State of Manipur through the Principal Secretary (Home), Govt. Of Manipur, Manipur Secretariat, South Block, PO & PS Imphal, Imphal West District, Manipur. 4. The Director General of Police, Manipur, Police HQs, PO & PS Imphal, West District, Maipur. 5. The Superintendent of Police, Tamenglong District, Manipur PO & PS Tamenglong District, Manipur. ..Respondents. BEFORE HON’BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE R. R .PRASAD HON’BLE MR.JUSTICE N.KOTISWAR SINGH For the Petitioner :: Mr. M.Rakesh, Advocate For the Respondents :: Mr. RS Reisang, Sr.G.A. Mr. S.Rupachandra,ASG Date of hearing :: 23.02.2017 Date of judgment/order :: ................. JUDGMENT & ORDER Chief Justice This application has been filed by the petitioner seeking compensation of a sum of Rs.20 lakhs on account of the death of his son, Guangsingam 2 Dangmei caused by the personnel of 10 th Assam Rifles in a fake/fictitious encounter. [2] It is the case of the petitioner that the petitioner’s son(victim), Guangsingam Dangmei, was studying in class-VIII in Tentmaker’s Academy, Longmai-III (Noney), Tamenglong District. While studying he was also helping his parents as a quarry labour and thereby petitioner’s son was earning at least Rs.600/-per day. -

1 District Census Handbook-Churachandpur

DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK-CHURACHANDPUR 1 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK-CHURACHANDPUR 2 DISTRICT CENSUSHANDBOOK-CHURACHANDPUR T A M T E MANIPUR S N A G T E L C CHURACHANDPUR DISTRICT I O L N R G 5 0 5 10 C T SENAPATI A T D I S T R I DISTRICT S H I B P Kilpmetres D To Ningthoukhong M I I From From Jiribam Nungba S M iver H g R n Ira N A r e U iv k R ta P HENGLEP ma Lei S Churachandpur District has 10 C.D./ T.D. Blocks. Tipaimukh R U Sub - Division has 2 T.D. Blocks as Tipaimukh and Vangai Range. Thanlon T.D. Block is co-terminus with the Thanlon r R e Sub-Diovision. Henglep T.D. Block is co-terminus with the v S i r e R v Churachandpur North Sub-Division. Churachandpur Sub- i i R C H U R A C H A N D P U R N O R T H To Imphal u l Division has 5 T.D. Blocks as Lamka,Tuibong, Saikot, L u D L g Sangaikot and Samulamlan. Singngat T.D. Block is co- l S U B - D I V I S I O N I S n p T i A a terminus with the Singngat Sub-Division. j u i R T u INDIAT NH 2 r I e v i SH CHURACHANDPUR C R k TUIBONG ra T a RENGKAI (C T) 6! ! BIJANG ! B G ! P HILL TOWN (C T) ! ZENHANG LAMKA (C T) 6 G! 6 3 M T H A N L O N CCPUR H.Q. -

List and Details of Resource Persons of Study Centres for D.El.Ed. Course (Manipur)

List and Details of Resource Persons of Study Centres for D.El.Ed. Course (Manipur) Sl. Name of Study Study Centre District Name of Resource Person School/ Institute of Resource Person No. Centre Code 1 Senapati Namdiliu Shingbengmai Maiba Govt. High School M. S. Thomas Bashou Koide Govt. High School Apex Christian H/S 471401001 Henia Kashi Prii Koide Govt. High School Pheiga Gangmei Kakhujei R. N. Phuba H/S 2 Senapati Th. Sharmila Devi DIET, Senapati Bethany Hr. Sec. A. Shambhuji DIET, Senapati 471401002 School H. Jamuna Devi DIET, Senapati Kh. Tombi Devi DIET, Senapati 3 Senapati L. Mirabati Lamlong Hr. Sec. School L. Nando Singh Lamlong Hr. Sec. School Bishnulal H/S 471401003 Tunapui Kamei Lamlong Hr. Sec. School Y . Sarita Devi Lamlong Hr. Sec. School 4 Senapati Ms. Loli Komuha Brook Dale Hr. Sec. School Brook Dale Hr. Sec. Mrs. Amos Pao Brook Dale Hr. Sec. School 471401004 School Baremron Surbala Kabui Willong H/S Rana R Maram Khullen High School 5 Senapati T. Thuamkhanvung Thangtong Hr. Sec. School Lalkai Chongloi Thangtong Hr. Sec. School Christian English H/S 471401005 Veihoinei Kipgen Goma Devi H/S Usham Nodiyachand Singh Thangtong Hr. Sec. School 6 Senapati O. Dashumati Chanu DIET, Senapati Daikho Va School G. Enakhunbi DIET, Senapati 471401006 (D.V) N. Santa Devi DIET, Senapati Y. Nandini Devi DIET, Senapati 7 Senapati Th. Sarojbala Damdei Christian College Damdei Christian Mercy Haokip Damdei Christian College 471401007 College Angom Thajamanbi Damdei Christian College Lhingjakim Lhouvum Damdei Christian College 8 Senapati S. Aruna Devi DIET, Senapati Th. Premila Devi DIET, Senapati DIET, Senapati 471401008 N. -

List of School

Sl. District Name Name of Study Centre Block Code Block Name No. 1 1 SENAPATI Gelnel Higher Secondary School 140101 KANGPOKPI 2 2 SENAPATI Damdei Christian College 140101 KANGPOKPI 3 3 SENAPATI Presidency College 140101 KANGPOKPI 4 4 SENAPATI Elite Hr. Sec. School 140101 KANGPOKPI 5 5 SENAPATI K.T. College 140101 KANGPOKPI 6 6 SENAPATI Immanuel Hr. Sec. School 140101 KANGPOKPI 7 7 SENAPATI Ngaimel Children School 140101 KANGPOKPI 8 8 SENAPATI T.L. Shalom Academy 140101 KANGPOKPI 9 9 SENAPATI John Calvin Academy 140102 SAITU 10 10 SENAPATI Ideal English Sr. Sec. School 140102 SAITU 11 11 SENAPATI APEX ENG H/S 140102 SAITU 12 12 SENAPATI S.L. Memorial Hr. Sec. School 140102 SAITU 13 13 SENAPATI L.M. English School 140102 SAITU 14 14 SENAPATI Thangtong Higher Secondary School 140103 SAIKUL 15 15 SENAPATI Christian English High School 140103 SAIKUL 16 16 SENAPATI Good Samaritan Public School 140103 SAIKUL 17 17 SENAPATI District Institute of Education & Training 140105 TADUBI 18 18 SENAPATI Mt. Everest College 140105 TADUBI 19 19 SENAPATI Don Bosco College 140105 TADUBI 20 20 SENAPATI Bethany Hr. Sec. School 140105 TADUBI 21 21 SENAPATI Mount Everest Hr. Sec. School 140105 TADUBI 22 22 SENAPATI Lao Radiant School 140105 TADUBI 23 23 SENAPATI Mount Zion Hr. Sec. School 140105 TADUBI 24 24 SENAPATI Don Bosco Hr. Sec. School 140105 TADUBI 25 25 SENAPATI Brook Dale Hr. Sec. School 140105 TADUBI 26 26 SENAPATI DV School 140105 TADUBI 27 27 SENAPATI St. Anthony’s School 140105 TADUBI 28 28 SENAPATI Samaritan Public School 140105 TADUBI 29 29 SENAPATI Mount Pigah Collage 140105 TADUBI 30 30 SENAPATI Holy Kingdom School 140105 TADUBI 31 31 SENAPATI Don Bosco Hr. -

File No. 8-63/2005-FC

10 Agenda -3 File No. 8-63/2005-FC 1. The State Government of Manipur vide its letter dated 12.11.2006 submitted a proposal to obtain prior approval of the Central Government, in terms of the Section-2 of the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 for diversion of 20,464 ha. forest land for construction of Tipaimukh Hydroelectric Project in Manipur. 2. Later on the State Government of Manipur vide their letter dated 4th April 2007 submitted a revised proposal for diversion of 25,822.14 hectares of forest land (and not 20,464 ha. as submitted earlier) for construction of said project. 3. Details indicated in the said revised proposal submitted by the State Government of Manipur are as below: FACT SHEET 1. Name of the Proposal Diversion of 25,822.14 ha. forest land for construction of Tipaimukh Hydroelectric Project in Manipur 2. Location: State Manipur District Churachandpur and Tamenglang 3. Particular of Forests Name of Forest Division Division Area of Forest land (ha.) Crown Area of Forest land for RF Un- Total Density Diversion classed Legal Status of Forest Southern Forest 2,812.50 5,938.00 8,750.50 Less land Div., than 40 Churachandpur % Density of Vegetation Western Forest 7,237.50 (area of Reserved Tree 30 Division, Forest and unclassed forest % Tamenglang has not been provided Bamboo separately 70 % Jiribam FD, 1,612 8,222.14 9,834.14 10% to Tamenglang 55 % 4. Species wise scientific Girth-class wise distribution of species available in the names and diameter forest land proposed for diversion are as below: class wise enumeration Division Girth Class (cm) of trees to be enclosed (in case of irrigation/hydel project enumeration in FRL, 20-50 50-100 100-150 150-200 200-250 250-300 Total FRL-2 mtr,& FRL-4 mtr. -

An Assessment of Dams in India's North East Seeking Carbon Credits from Clean Development Mechanism of the United Nations Fram

AN ASSESSMENT OF DAMS IN INDIA’S NORTH EAST SEEKING CARBON CREDITS FROM CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM OF THE UNITED NATIONS FRAMEWORK CONVENTION ON CLIMATE CHANGE A Report prepared By Mr. Jiten Yumnam Citizens’ Concern for Dams and Development Paona Bazar, Imphal Manipur 795001 E-add: [email protected], [email protected] February 2012 Supported by International Rivers CONTENTS I INTRODUCTION: OVERVIEW OF DAMS AND CDM PROJECTS IN NORTH EAST II BRIEF PROJECT DETAILS AND KEY ISSUES AND CHALLENGES PERTAINING TO DAM PROJECTS IN INDIA’S NORTH EAST SEEKING CARBON CREDITS FROM CDM MECHANISM OF UNFCCC 1. TEESTA III HEP, SIKKIM 2. TEESTA VI HEP, SIKKIM 3. RANGIT IV HEP, SIKKIM 4. JORETHANG LOOP HEP, SIKKIM 5. KHUITAM HEP, ARUNACHAL PRADESH 6. LOKTAK HEP, MANIPUR 7. CHUZACHEN HEP, SIKKIM 8. LOWER DEMWE HEP, ARUNACHAL PRADESH 9. MYNTDU LESHKA HEP, MEGHALAYA 10. TING TING HEP, SIKKIM 11. TASHIDING HEP, SIKKIM 12. RONGNINGCHU HEP, SIKKIM 13. DIKCHU HEP, SIKKIM III KEY ISSUES AND CHALLENGES OF DAMS IN INDIA’S NORTH EAST SEEKING CARBON CREDIT FROM CDM IV CONCLUSIONS V RECOMMENDATIONS VI ANNEXURES A) COMMENTS AND SUBMISSIONS TO CDM EXECUTIVE BOARD ON DAM PROJECTS FROM INDIA’S NORTH EAST SEEKING REGISTRATION B) MEDIA COVERAGES OF MYNTDU LESHKA DAM SEEKING CARBON CREDITS FROM CDM OF UNFCCC GLOSSARY OF TERMS ACT: Affected Citizens of Teesta CDM: Clean Development Mechanism CC : Carbon Credits CER: Certified Emissions Reductions CWC: Central Water Commission DPR: Detailed Project Report DOE: Designated Operating Entity DNA: Designated Nodal Agency EAC: -

(Ii) the Organization Will Not Obtain Grant for the Same Purpose Or Activity from Any Other Ministry Or Department of Government

Re-imbursement of Expenditure UC not required No.8- 257/2013-leadership Government of India Ministry of Minority Affairs 11 th Floor, Paryavaran Bhavan, C.G.O.Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003 Dated: 11 )11 1'4; 2015 To The Pay & Accounts Officer, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Paryavaran Bhavan, CGO Complex, New Delhi Subject: Release of 2" installment (40%) of non-residential of non-recurring Grant-in-Aid for the year 2013-14 to `Goodwill Group for Rural and Urban Development , Thanagong Village,Khoupum BPO, Nungba Sub- Divi,Tamenglong Manipur-795147' for organizing Leadership Development training programme at Tamenglong (Manipur) under the "Scheme for Leadership Development of Minority Women" during the year 2014-15. Sir, In continuation to this Ministry's sanction letter of even dated 2-1 frni. b91 , I am directed to convey the sanction of the President of India for the release an amount of Rs. 1,43,100/- (Rupees One Lakh Forty Three thousand One hundred only), as 2" d installment (40%) of Non-Residential training out of the total sanctioned amount of Rs. 3,57,750/-(Rupees three lakh fifty Seven Thousand seven hundred and fifty only) as Non-recurring grant-in-aid for the year 2013-14 during the year 2014-15 , under the scheme for Leadership Development of Minority Women to the 'Goodwill Group for Rural and Urban Development , Thanagong Village,Khoupum BPO,Nungba Sub- Divi,Tamenglong Manipur-795147 ' on the following terms and conditions: 2 (i) Grant-in-aid has been given to the above mentioned organizations on the basis of the recommendation of Government of Manipur. -

Impacts of Tipaimukh Dam on the Down-Stream Region in Bangladesh: a Study on Probable EIA

www.banglajol.info/index.php/JSF Journal of Science Foundation, January 2015, Vol. 13, No.1 pISSN 1728-7855 Original Article Impacts of Tipaimukh Dam on the Down-stream Region in Bangladesh: A Study on Probable EIA M. Asaduzzaman1, Md. Moshiur Rahman 2 Abstract Amidst mounting protests both at home and in lower riparian Bangladesh, India is going ahead with the plan to construct its largest and most controversial 1500 mw hydroelectric dam project on the river Barak at Tipaimukh in the Indian state Manipur. In the process, however, little regard is being paid to the short and long-term consequences on the ecosystem, biodiversity or the local people in the river’s watershed and drainage of both upper and low reparian countries . This 390 m length and 162.8 m. high earthen-rock filled dam also has the potential to be one of the most destructive. In India too, people will have to suffer a lot for this mega project. The total area required for construction including submergence area is 30860 ha of which 20797 ha is forest land, 1195 ha is village land, 6160 ha is horticultural land, and 2525 ha is agricultural land. Cconstruction of the massive dam and regulate water flow of the river Barak will have long adverse effects on the river system of Surma and Kushiyara in the north-eastern region of Bangladesh which will obviously have negative impacts on ecology, environment, agriculture, bio-diversity, fisheries, socio-economy of Bangladesh. To assess the loss of Tipaimukh dam on downstream Bangladesh, an Eivironmental Impact Assessment (EIA) has been conducted based on probable affect parametes. -

Slno Name Designation 1 S.Nabakishore Singh Assoc.Prof 2 Y.Sobita Devi Asso.Proffessor 3 Kh.Bhumeshwar Singh

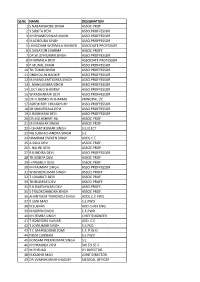

SLNO NAME DESIGNATION 1 S.NABAKISHORE SINGH ASSOC.PROF 2 Y.SOBITA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 3 KH.BHUMESHWAR SINGH. ASSO.PROFFESSOR 4 N.ACHOUBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 5 LUNGCHIM WORMILA HUNGYO ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR 6 K.SANATON SHARMA ASSOC.PROFF 7 DR.W.JOYKUMAR SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 8 N.NIRMALA DEVI ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR 9 P.MUNAL SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 10 TH.TOMBI SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 11 ONKHOLUN HAOKIP ASSO.PROFFESSOR 12 M.MANGLEMTOMBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 13 L.MANGLEMBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 14 LUCY JAJO SHIMRAY ASSO.PROFFESSOR 15 W.RADHARANI DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 16 DR.H.IBOMCHA SHARMA PRINCIPAL I/C 17 ASHOK ROY CHOUDHURY ASSO.PROFFESSOR 18 SH.SHANTIBALA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 19 K.RASHMANI DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 20 DR.MD.ASHRAF ALI ASSOC.PROF 21 M.MANIHAR SINGH ASSOC.PROF. 22 H.SHANTIKUMAR SINGH S.E,ELECT. 23 NG SUBHACHANDRA SINGH S.E. 24 NAMBAM DWIJEN SINGH ADDL.C.E. 25 A.SILLA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 26 L.NALINI DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 27 R.K.INDIRA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 28 TH.SOBITA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 29 H.PREMILA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 30 KH.RAJMANI SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 31 W.BINODKUMAR SINGH ASSCO.PROFF 32 T.LOKABATI DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 33 TH.BINAPATI DEVI ASSCO.PROFF. 34 R.K.RAJESHWARI DEVI ASSO.PROFF., 35 S.TRILOKCHANDRA SINGH ASSOC.PROF. 36 AHANTHEM TOMCHOU SINGH ADDL.C.E.PWD 37 K.SANI MAO S.E.PWD 38 N.SUBHAS ADD.CHIEF ENG. 39 N.NOREN SINGH C.E,PWD 40 KH.TEMBA SINGH CHIEF ENGINEER 41 T.ROBINDRA KUMAR ADD. C.E. -

To Improve the Durability, Function and Life of Infrastructure in NER, While Bringing Down the Life Cycle Cost Ofthe Projects;

Progress on Scheme for Promoting the Usage ofGeotechnical Textiles in North East Reeion (NER) as on 01.09.2017 Ministry oi Textiles, Govemment of India has launched a Scheme for Promoting Usage of Geotechnical textiles in North Eastem Region in the 12th five year plan with an outlay ofRs. 427 crore for a period of 5 years from 2014-15 to 2018-19. The aim is to utilize Geotextiles in development of the infrastructure of the NE states by providing technological and financial support by meeting additionality in project cost due to the usage of Geotextiles in existing/ new project in road, hil[/ slope protection and water reservoir. The Scheme was approved on 03rd Deeember 2014 & launched on24.03.2015. Geo-climatic and topographic characteristics in NER make infrastiucture in this region amenable to the use of geotechnical textiles. The region is fraught with heavy rainfall, fragile terain, landslides and sinking zones, river bank erosion, high seismic activity, weak soil conditions, young mountains, and problems in water harvesting and storage. The North Eastern Region of India is yet ro adopt this innovative technology, baning a few roads in Assam, which were taken-up as pilot projects under PMGSY. The scheme has the following basic objectives To demonstrate use of geotechnical textiles as a modern cost-effective technology in the development of infrastructure in fragile geological conditions of NER; To improve the durability, function and life of infrastructure in NER, while bringing down the life cycle cost ofthe projects; llt, To promote the use of geotechnical textiles material and create a market for these products in the NER by inducing demand in infrastructure development; lv.