Influences of the Ideas of Jay Hambidge on Art and Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Painting by the Numbers: a Porter Postscript

Painting by the Numbers: A Porter Postscript Chris Bartlett Art Department Towson University 8000 York Road Towson, MD, 21252, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract At the 2005 Bridges conference the author presented a paper titled, “Fairfield Porter’s Secret Geometry”. Porter (1907-1975), an important American painter, is known for his “naturalness” and seems to eschew any system of proportioning. This paper briefly traces other influences on Porter’s use of geometry in art and offers an analysis of two more of his paintings to reveal detailed and sophisticated geometric structures based on the Golden Ratio and Dynamic Symmetry. Introduction Artists throughout history have sought a key to beauty in proportioning systems in composition, a procedural method for compositional structure. Starting in the late 19th century there was a general resurgence of interest in geometrical structure as a basis for painting. Artists were researching aids to producing analogous and self-similar areas and repetitions of ratios in assigning the elements of a painting. In the 1920’s in America compositional methods gained new popularity fueled by Matila Ghyka and Jay Hambidge such that Milton Brown was prompted to title a critical article in the Magazine of Art, “Twentieth Century Nostrums: Pseudo-Scientific Theory in American Painting”. [1] More recently there have been growing circles criticizing the hegemony of the Golden Mean as a universal aesthetic panacea. [2] The principle of beauty underlining the application of the Golden Ratio and Dynamic Symmetry proportioning in a composition is not irrefutable, but what seems like a more useful exercise than to debate research in perception of elegant proportion is to look at the works of artists who seem to have fallen under its spell. -

Aesthetical Issues of Leonardo Da Vinci's and Pablo Picasso's

heritage Article Aesthetical Issues of Leonardo Da Vinci’s and Pablo Picasso’s Paintings with Stochastic Evaluation G.-Fivos Sargentis * , Panayiotis Dimitriadis and Demetris Koutsoyiannis Laboratory of Hydrology and Water Resources Development, School of Civil Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, Heroon Polytechneiou 9, 157 80 Zographou, Greece; [email protected] (P.D.); [email protected] (D.K.) * Correspondence: fi[email protected] Received: 7 April 2020; Accepted: 21 April 2020; Published: 25 April 2020 Abstract: A physical process is characterized as complex when it is difficult to analyze or explain in a simple way. The complexity within an art painting is expected to be high, possibly comparable to that of nature. Therefore, constructions of artists (e.g., paintings, music, literature, etc.) are expected to be also of high complexity since they are produced by numerous human (e.g., logic, instinct, emotions, etc.) and non-human (e.g., quality of paints, paper, tools, etc.) processes interacting with each other in a complex manner. The result of the interaction among various processes is not a white-noise behavior, but one where clusters of high or low values of quantified attributes appear in a non-predictive manner, thus highly increasing the uncertainty and the variability. In this work, we analyze stochastic patterns in terms of the dependence structure of art paintings of Da Vinci and Picasso with a stochastic 2D tool and investigate the similarities or differences among the artworks. Keywords: aesthetic of art paintings; stochastic analysis of images; Leonardo Da Vinci; Pablo Picasso 1. Introduction The meaning of beauty is linked to the evolution of human civilization, and the analysis of the connection between the observer and the beauty in art and nature has always been of high interest in both philosophy and science. -

John Sharp Spirals and the Golden Section

John Sharp Spirals and the Golden Section The author examines different types of spirals and their relationships to the Golden Section in order to provide the necessary background so that logic rather than intuition can be followed, correct value judgments be made, and new ideas can be developed. Introduction The Golden Section is a fascinating topic that continually generates new ideas. It also has a status that leads many people to assume its presence when it has no relation to a problem. It often forces a blindness to other alternatives when intuition is followed rather than logic. Mathematical inexperience may also be a cause of some of these problems. In the following, my aim is to fill in some gaps, so that correct value judgements may be made and to show how new ideas can be developed on the rich subject area of spirals and the Golden Section. Since this special issue of the NNJ is concerned with the Golden Section, I am not describing its properties unless appropriate. I shall use the symbol I to denote the Golden Section (I |1.61803 ). There are many aspects to Golden Section spirals, and much more could be written. The parts of this paper are meant to be read sequentially, and it is especially important to understand the different types of spirals in order that the following parts are seen in context. Part 1. Types of Spirals In order to understand different types of Golden Section spirals, it is necessary to be aware of the properties of different types of spirals. This section looks at spirals from that viewpoint. -

Toward How to Add an Aesthetic Image to Mathematics Education

TOWARD HOW TO ADD AN AESTHETIC IMAGE TO MATHEMATICS EDUCATION Paul Betts University of Winnipeg [email protected] Abstract: The goal of this paper is to suggest how an aesthetic image can be added to mathematics education. Calls for reform in mathematics education (e.g., National Council for Teachers of Mathematics, 1989, 2000) are premised on shifting teacher attention from an absolutist toward a social constructivist philosophy of mathematics and mathematics education. The goal of reform is success for all students of mathematics. In a previous paper, I used ideas from art education to suggest that success for all might be achieved by fostering an aesthetic image of mathematics (Betts & McNaughton, 2003). This paper continues the argument by shifting from questions of why to how. Introduction In 1989, the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) published an influential mathematics curriculum framework document (see National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 1989) calling for reform in mathematics and success for all mathematics students. This call for reform is based on social constructivism as a philosophy of mathematics and mathematics education. Proponents of social constructivism, as a philosophy of mathematics, view mathematics as fallible, changing and a product of human endeavor (Ernest, 1998). For example, the genesis of mathematical knowledge is a continual cycle of conjecture and refutation, and deduction is not the logic of mathematical discovery (Lakatos, 1976). In other words, mathematical truths are socially constructed via a process of error correction. Social constructivsm as a philosophy of mathematics education is based on fostering opportunities for students to experience, discover, discuss and re-construct the socially negotiated nature of mathematics. -

An Annotated Bibliography of Books for Architecture and Mathematics

The Virtual Library An Annotated Bibliography of Books for Architecture and Mathematics ACKERMAN,JAMES S. Distance Points: Essays in Theory and Renaissance Art and Architecture. (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1991). Referenced in Lionel March’s article, NNJ vol. 3 no. 2. ———. Origins, Imitation, Conventions (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2002). Reviewed by Michael Chapman in the NNJ vol. 5 no. 1. AICHER,OTL. Analogous and Digital (Berlin: Ernst & Sohn, 1994). Referenced in Marco Frascari’s article in NNJ vol. 1. ALBERTI,LEON BATTISTA. The Ten Books of Architecture, 1755. (Rpt. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1986). Referenced in Marco Frascari’s article in NNJ vol. 1 no. 3 and in Reza Sarghangi’s article in NNJ vol. 1. ———. On the Art of Building in Ten Books. Joseph Rykwert (Introduction), Robert Tavernor and Neil Leach, trans. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991). Referenced in Stephen Wassell’s article in NNJ vol. 1. ALEXANDER,CHRISTOPHER. A Pattern Language (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977). Referenced in Nikos Salingaros’ article in NNJ vol. 1. ———. A Timeless Way of Building (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979). Referenced in Nikos Salingaros’ article in NNJ vol. 1. ARTMANN,BENNO. Euclid: The Creation of Mathematics (Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 1999). This is the long awaited book by Benno Artmann, who presented a paper on the Cloisters of Hauterive at Nexus ‘96. Reviewed by Kim Williams in NNJ vol.2. BALMAND,CECIL. Number Nine: The Search for the Sigma Code (Munich: Prestel,1999). Reviewed by Jay Kappraff in the NNJ vol. 2. BARRALLO,JAVIER (ed.). Mathematics and Design 98. Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Mathematics and Design. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9123572 Art and mathematics: Enhancing achievement through curricular design Winter, June Frances M., Ph.D. The American University, 1991 Copyri^t ©1991 by Winter, June Prances M. -

Miszellaneen Miscellanea

miszellaneen MISCELLANEA c.g. boerner in collaboration with harris schrank fine prints Israhel van Meckenem ca. 1440–45 – d. Bocholt 1503 1. Die Auferstehung – The Resurrection (after the Master E.S.) ca. 1470 engraving with extensive hand-coloring in red, blue, green, reddish-brown and gold leaf; 94 x 74 mm (3 11�16 x 2 ⅞ inches) Lehrs and Hollstein 140 provenance C.G. Boerner, Leipzig, sale 153, May 3–4, 1927, lot 43 sub-no. 49 (ill. on plate 3) S.F.C. Wieder, Noordwijk, The Netherlands William H. Schab Gallery, New York, cat. 40 [1963], no. 64 (the still-intact manuscript), the Meckenem ill. on p. 69 private collection, Switzerland Sotheby’s, London, December 4, 1969, lot 18 William H. Schab Gallery, New York, cat. 52, 1972, no. 46 (ill. in color) C.G. Boerner, Düsseldorf, acquired April 25, 1972 private collection, Germany Sotheby’s, London, December 3–4, 1987, lot 579 (GBP 27,500) private collection Unikum. Very little is known about the early life of Israhel van Meckenem. His family probably came from Meckenheim near Bonn. He might have received his first artistic training with the so- called Master of the Berlin Passion who was active in the Rhine-Meuse region in 1450–70 (and whom Max Geisberg even tried to identify as Van Meckenem’s father). This is supported by 13 copies that Van Meckenem made after prints by this early “Anonymous.” However, the Master E.S. played an even more important role in the formation of the young artist. He worked in the Upper Rhine valley, most likely in Strasbourg, and his importance for the development of the relatively new medium of engraving can hardly be overestimated. -

Hateful Contraries: Studies in Literature and Criticism

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Comparative Literature Arts and Humanities 12-31-1965 Hateful Contraries: Studies in Literature and Criticism W. K. Wimsatt Yale University Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Wimsatt, W. K., "Hateful Contraries: Studies in Literature and Criticism" (1965). Comparative Literature. 9. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_comparative_literature/9 Hateful Contraries This page intentionally left blank Hateful Contraries STUDIES IN LITERATURE AND CRITICISM By W. K. WIMSATT With an Essay on English Meter Written in Collaboration with Monroe C. Beardsley KENTUCKY PAPERBACKS UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY PRESS Lexington, 1966 Copyright© 1965 by the University of Kentucky Press Printed in the United States of America by the University of Kentucky Printing Division Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 65-11823 F. W. H. HUMANITATE INSIGNI DOCTOR! ET DUCTORI D. D. D. W. K. W. This page intentionally left blank ACKNOWLEDGMENT THE ESSAYS in criticism and critical history which compose this book were published (all but one), in their original versions, over a period of about twelve years, from 1950 to 1962. The first essay in the collection, "Horses of Wrath: Recent Critical Lessons," has been rewritten from parts of the fol lowing three: "Criticism Today: A Report from America," in Essays in Criticism, VI (January, 1956); "Poetic Tension: A Summary," in the New Scholasticism, XXXII (January, 1958); and "Horses of Wrath: Recent Critical Lessons," in Essays in Criticism, XII (January, 1962). -

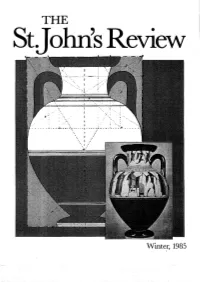

Winter, 1985 '· Editor: to the Editor: J

THE St. o 'sReview I : ... ::: ............... ~--'~---1. ....... I ' ··.. I )·<·· ·.. : .. · _:.-·· •. - .• Winter, 1985 '· Editor: To the editor: J. Walter Sterling At the urging of alumni and col leagues, and with the co-operation of Mrs. Klein, I am undertaking to Poetry Editor: gather material for a brieflife ofjacob Richard Freis Klein. I shall be pleased to have documents, reminiscences, or other Editorial Assistant: memorabilia. Jason Walsh I would be particularly pleased to hear from alumni who were members Editorial Board: of his classes in his first years of Eva Brann teaching, especially his first seminar. S. Richard Freis, Alumni representative Wye J. Allanbrook Joe Sachs St. John's College Cary Stickney Curtis A. Wilson Unsolicited articles, storieS, and poems are welcome, but should be accom panied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope in each instance. Reasoned comments are also welcome. The St. John's Review (formerly The Col lege) is published by the Office of the Dean, St. John's College, Annapolis, Maryland 21404. Edwin J. Delattre, President, George Do'skow, Dean. Published thrice yearly, in the winter, spring, and summer. For those not on the distribution list, subscriptions: $12.00 yearly, $24.00 for two years, or $36.00 for three years, payable in ad vance. Address all correspondence to The St. John's Review, St.John's College, Annapolis, Maryland 21404. Volume XXXVI, Number 1 Winter, 1985 © 1985 St. John's College; All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited. ISSN 0277-4720 Cover: A Black-Figured Amphora from the Boston Museum (Drawn, measured and analyzed by L.D. -

Aistarch-N.-1.Pdf

Edizioni Caracol Studi e Ricerche di Storia dell’Architettura Rivista dell’Associazione Italiana Storici dell’Architettura anno I - 2017 NUMERO 1 Direttore Responsabile Marco Rosario Nobile Comitato scientifico Donata Battilotti, Federico Bellini, Amedeo Belluzzi, Federico Bucci, Claudia Conforti, Giovanna Curcio, Francesco Dal Co, Alessandro De Magistris, Vilma Fasoli, Adriano Ghisetti Giavarina, Anna Giannetti, Antonella Greco, Fulvio Irace, Giovanni Leoni, Costanza Roggero, Rosa Tamborrino, Alessandro Viscogliosi Capo Redattore Francesca Mattei Redazione Armando Antista, Giovanni Bellucci, Lorenzo Ciccarelli, Rosa Maria Giusto, Anna Pichetto Fratin, Monica Prencipe, Domenica Sutera Impaginazione e grafica Giovanni Bellucci Le proposte, nel rispetto delle norme editoriali, devono essere inviate all’indi- rizzo [email protected]. I saggi, valutati preventivamente dal con- siglio direttivo e dal comitato editoriale, sono valutati dai referees del comitato scientifico secondo il criterio del double blind peer review. La redazione declina ogni responsabilità per i materiali inviati in visione non espressamente richiesti. Vietata la riproduzione o duplicazione con qualsiasi mezzo. Per abbonamenti rivolgersi a [email protected] © 2017 Caracol, Palermo Edizioni Caracol s.n.c. - via Villareale, 35 - 90141 Palermo In copertina: e-mail:_ [email protected] Quartiere Le Vallette: gli edifici del settore G in costruzione nel 1960 ISSN: 2532-2699 (Archivio ATC Torino, Faldone n.1 Busta 13) ISBN: 978-88-98546-81-7 INDICE Editoriale 6 MARCO ROSARIO NOBILE Saggi Vanishing architects, shifting nations. Writing the history of Bohemian 8 DIRK DE MEYER Baroque architecture, 1880-1945 Francesco Maria Ricchino (1584-1658), 28 ISABELLA BALESTRERI progetti milanesi fra storia e storiografia L’oscuro contributo degli “inclassificabili” storici-ingegneri civili italiani 48 GIOVANNI BELLUCCI allo studio della storia dell’ingegneria e dell’architettura contemporanea Lo specchio distorto di un quartiere. -

The Plan-Net As a Geometry for Analysis of Pre-Modern Architectural Design and Layout

THE PLAN-NET AS A GEOMETRY FOR ANALYSIS OF PRE-MODERN ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN AND LAYOUT Arthur John Lawton submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology December 2013 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Doctoral Committee Henry Glassie, Ph.D. Jason Jackson, Ph.D Pravina Shukla, Ph. D. Eric Sandweiss, Ph. D. November 12, 2013 ii Copyright © 2013 Arthur J. Lawton iii Arthur Lawton PLAN-NET GEOMETRY AND ANALYSIS OF PRE-MODERN ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN AND LAYOUT Limited Pre-Modern calculating skills favored geometry for design and layout. Technical limitations precluding durable, detailed measured drawings favored sequentially proportional steps transmitting information from design to construction. The Ancient Egyptian phrase “Casting the plan-net on the ground” implies a rectilinear network of geometrical lines serving to locate plan elements on the ground. Reconstruction of Polykleitos’ Kanon demonstrates design parameters based on sequential proportionality that extracts a “correctly” proportioned human figure from an original square base figure. Fifteenth century booklets describe extraction of a completed architectural form from the base figure. Iconographic sources trace these Ancient World methods from their use in practical implementation to symbolization as eighteenth century remembrances in Free Mason paraphernalia. To associate floor plan elements with a rectilinear network, plan-net geometry manipulates proportional relationships of squares and rectangles in sequentially proportional steps. Geometrical design steps by divider and straightedge are identical to ground-lines steps by cord and peg, eliminating calculation from scale change. -

Jay Hambidge & Charles Henry

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 369 691 SO 023 791 AUTHOR McWhinnie, Harold J. TITLE The Development of a Psychological Aesthetic: Jay Hambidge & Charles Henry. PUB DATE 91 NOTE 17p. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Art; *Art Education; *Art History; *Artists; Higher Education; Interdisciplinary Approach; *Mathematics IDENTIFIERS Golden Section; *Greek Theory; *Hambidge (JaY); Hambidge (Mary Crovatt); Henry (Charles) ABSTRACT This article reviews several movements in late 19th and early 20th century art and psychological research that are related to the early Greek method of proportional analysis generally known as the Golden Section. The document discusses the work of the artist Jay Hambidge on the nature of Greek art and design and his thcory of dynamic symmetry. Hambidge and his wife, Mary, have been neglected by art historians because their efforts have not been seen as part of a larger development within the story of the modern movement. The view of Plato that states th., mathematical objects are intermediate between the ideas and the sensible world, reflect eternal relationships, and are separate from the external world, is contrasted to that of Aristotle that while mathematical objects are intermediate between ideal being and the sensible world, they cannot be deducted from an analysis of being, and have no separate existence. Interrelationships between art and science that can be related to the newest developments in science, computer graphics, and computer assisted design re examined. Relativity is seen as complex not because of the mathematics, but because of its novelty in providing a simpler view of the world. The emphasis of this research is on the continuity of research and ideas in the arts as well as the sciences from the past to the present.