Intelligence Testing at Whittier School, 1890–1920

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 11 Case No. 21-10632 (MBK)

Case 21-10632-MBK Doc 249 Filed 04/06/21 Entered 04/06/21 16:21:35 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 92 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY In re: Chapter 11 L’OCCITANE, INC., Case No. 21-10632 (MBK) Debtor. Judge: Hon. Michael B. Kaplan CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I, Ana M. Galvan, depose and say that I am employed by Stretto, the claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned case. On April 2, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following documents to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A, and via electronic mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit B: Notice of Deadline for Filing Proofs of Claim Against the Debtor L’Occitane, Inc. (attached hereto as Exhibit C) [Customized] Official Form 410 Proof of Claim (attached hereto as Exhibit D) Official Form 410 Instructions for Proof of Claim (attached hereto as Exhibit E) Dated: April 6, 2021 /s/ Ana M. Galvan Ana M. Galvan STRETTO 410 Exchange, Suite 100 Irvine, CA 92602 Telephone: 855-434-5886 Email: [email protected] Case 21-10632-MBK Doc 249 Filed 04/06/21 Entered 04/06/21 16:21:35 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 92 Exhibit A Case 21-10632-MBK Doc 249 Filed 04/06/21 Entered 04/06/21 16:21:35 Desc Main Document Page 3 of 92 Exhibit A Served via First-Class Mail Name Attention Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 City State Zip Country 1046 Madison Ave LLC c/o HMH Realty Co., Inc., Rexton Realty Co. -

Gateway Final Municipal Service Review

GATEWAY FINAL MUNICIPAL SERVICE REVIEW Report to the Local Agency Formation Commission for Los Angeles County Prepared by Burr Consulting November 30, 2005 GATEWAY FINAL MUNICIPAL SERVICE REVIEW Report to the Local Agency Formation Commission for Los Angeles County Submitted to: LAFCO for Los Angeles County Larry J. Calemine, Executive Officer 700 North Central Blvd, Suite 350 Glendale, CA 91203 (818) 254-2454 Submitted by: Burr Consulting Beverly Burr, Project Coordinator 612 N. Sepulveda Blvd, Suite 8 Los Angeles, CA 90049 (310) 889-0077 November 30, 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .........................................................................................................................................1 MUNICIPAL SERVICE REVIEW FINDINGS....................................................................................................................2 SPHERE OF INFLUENCE FINDINGS ..............................................................................................................................5 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................6 LAFCO OVERVIEW...................................................................................................................................................6 MUNICIPAL SERVICE REVIEW ORIGINS .....................................................................................................................7 SPHERE OF INFLUENCE UPDATES.............................................................................................................................10 -

Short Range Transportation Plan FY 2015 - 2017

Short Range Transportation Plan FY 2015 - 2017 City of Montebello Transportation Department City of Montebello – Transportation Department FY 2015 - 2017 SHORT RANGE TRANSPORTATION PLAN Table of Contents SECTION 1 – OVERVIEW OF THE TRANSIT SYSTEM 1.1 History of the City of Montebello and Montebello Bus Lines ................................ 3 1.2 Governance and Organizational Structure ............................................................. 4 1.3 Transit Services and Areas Served .......................................................................... 5 1.4 Ridership ................................................................................................................. 7 1.5 Fare Structure ......................................................................................................... 7 1.6 Fleet, Facility and Equipment ................................................................................. 8 SECTION 2 – BUDGET, FUNDING, AND REGULATION 2.1 Operating and Capital Budget............................................................................... 10 2.2 Funding Sources.................................................................................................... 10 2.3 Regulatory Requirements ..................................................................................... 11 SECTION 3 – ACCOMPLISHMENTS, GOALS AND OBJECTIVES 3.1 Past Accomplishments........................................................................................... 13 3.2 Goals and Objectives ............................................................................................ -

La Rhonda Apartments 7621 WASHINGTON AVENUE, WHITTIER, CA 90602

La Rhonda Apartments 7621 WASHINGTON AVENUE, WHITTIER, CA 90602 Offering Memorandum NON-ENDORSEMENT & DISCLAIMER NOTICE CONFIDENTIALITY & DISCLAIMER The information contained in the following Marketing Brochure is proprietary and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from Marcus & Millichap and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of Marcus & Millichap. This Marketing Brochure has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. Marcus & Millichap has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation, with respect to the income or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCB’s or asbestos, the compliance with State and Federal regulations, the physical condition of the improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant’s plans or intentions to continue its occupancy of the subject property. The information contained in this Marketing Brochure has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, Marcus & Millichap has not verified, and will not verify, any of the information contained herein, nor has Marcus & Millichap conducted any investigation regarding these matters and makes no warranty or representation whatsoever regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information provided. All potential buyers must take appropriate measures to verify all of the information set forth herein. -

Csa Welfare Fund

\ ,,"-CSA WELFARE FUND Hearing Aid Providers SEPTEMBER 2008 EDITION TABLE OF CONTENTS COMPREHENSIVE PROFESSIONAL SERVICES , HEARx ...•...........................•.......•................. 5 GENERAL HEARING SERVICES (General Vision Services) •...........•. 9 CRYSTAL CLEARIBELTONE .•...............•.................... 12 INDEPENDENT DEALERS •.............•.•.•.................•... 56 COMPREHENSIVE PROFESSIONAL SERVICES BROOKLYN MANHATTAN QUEENS Dennis Kisiel, PhD. J. Eduardo Bravo Lewis Breslau Audiology Affiliates a.k.s. Audio Help Associates Hearing Health Associates AB Hearing Aid Center 1421 Third Avenue 32-44 Francis Lewis Blvd 142 Joralemon Street, #6A New York, NY 10028 Bayside, New York 11358 Brooklyn, New York 11201 866-530-7500 718-460-3100 718.875-3131 J. Eduardo Bravo John Kenul Dennis Kisiel, PhD. Audio Help Associates Otohealth Hearing Aid Centers Audiology Affiliates a.k.s. 5t Vincent's Hospital 38-03 31 Avenue AB Hearing Aid Center 153 West 11th Street Astoria, NY 11103 355 Ovington Street, #102 New York, NY 10011 718-274.4327 Brooklyn, NY 11209 866-530-7500 718-858-6734 Mindy Duboff Laurence Deutsch, PhD. 107-21 Queens Blvd Mrs. Mandel Pelham Audiology Associates Forest Hills, NY 11375 228 Livingston Street PC/Audlonics 718-520-1594 (Near Macy's Annex) 515 Madison Avenue, Suite 2302 Brooklyn, New York 11201 New York, NY1oo22 J. Eduardo Bravo 718-625-2905 or 2137 212-755-5100 Audk> Help Associates 30-16 30th Drive Mark Zelnick Sheila Flaxman Astoria, NY 11102 2204 Flatbush Avenue New York Audiology Center 866-530-7500 At Avenue "R" 444 East 82 Street, #280 Brooklyn, New York 11234 New York, NY1OO28 Gary Rubin 718-252.0057/0058 212-499-0691 FranhilJ Opitcal & Hearing 87-87 Francis Lewis Blvd Mark Zelnick Kung Y. -

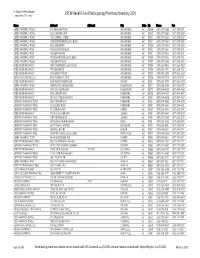

Network Pharmacy Listing from CVS from Optum

To Display the Find toolbar - select key CTRL and F UFCW Benefit Fund Participating Pharmacy Directory 2021 Name Address1 Address2 City State Zip Phone Fax CARRS PHARMACY #0520 3101 PENLAND PKWY ANCHORAGE AK 99508 (907) 339-5260 (907) 339-5219 CARRS PHARMACY #0720 2920 SEWARD HWY ANCHORAGE AK 99503 (907) 339-0660 (907) 339-0619 CARRS PHARMACY #1802 1340 GAMBELL STREET ANCHORAGE AK 99501 (907) 339-0260 (907) 339-0219 CARRS PHARMACY #1805 1650 W NORTHERN LIGHTS BLVD ANCHORAGE AK 99517 (907) 339-0560 (907) 339-0519 CARRS PHARMACY #1809 5600 DEBARR RD ANCHORAGE AK 99504 (907) 339-0960 (907) 339-0919 CARRS PHARMACY #1812 4000 W DIMOND BLVD ANCHORAGE AK 99502 (907) 339-1260 (907) 339-1219 CARRS PHARMACY #1813 1501 HUFFMAN RD ANCHORAGE AK 99515 (907) 339-1360 (907) 339-1319 CARRS PHARMACY #1817 7731 E NORTHERN LIGHTS BLVD ANCHORAGE AK 99504 (907) 339-1760 (907) 339-1719 CARRS PHARMACY #2628 1725 ABBOTT ROAD ANCHORAGE AK 99507 (907) 339-2860 (907) 339-2819 FRED MEYER PHARMACY 1000 E NORTHERN LIGHTS BLVD ANCHORAGE AK 99508 (907) 264-9633 (907) 264-9627 FRED MEYER PHARMACY 7701 DEBARR RD ANCHORAGE AK 99504 (907) 269-1733 (907) 269-1727 FRED MEYER PHARMACY 2300 ABBOTT ROAD ANCHORAGE AK 99507 (907) 365-2033 (907) 365-2027 GENOA HEALTHCARE, LLC 4020 FOLKER ST STE 5 ANCHORAGE AK 99508 (907) 891-7079 (907) 331-3147 FRED MEYER PHARMACY 2000 WEST DIMOND BLVD DIMOND AK 99515 (907) 267-6733 (907) 267-6739 CARRS PHARMACY #1807 11431 BUSINESS BOULEVARD EAGLE RIVER AK 99577 (907) 726-0760 (907) 726-0719 FRED MEYER PHARMACY 13401 OLD GLENN HWY EAGLE RIVER AK -

Regular Meeting Agenda

CITY COUNCIL MEETING AGENDA CITY OF MONTEBELLO CITY COUNCIL/SUCCESSOR AGENCY CITY HALL COUNCIL CHAMBERS 1600 WEST BEVERLY BOULEVARD MONTEBELLO, CALIFORNIA1 1[2] WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 18, 2020 5:30 P.M. MONTEBELLO CITY COUNCIL SALVADOR MELENDEZ MAYOR KIMBERLY A. COBOS-CAWTHORNE ANGIE M. JIMENEZ MAYOR PRO TEM COUNCILMEMBER DAVID N. TORRES JACK HADJINIAN COUNCILMEMBER COUNCILMEMBER CITY CLERK CITY TREASURER IRMA BARAJAS RAFAEL GUTIERREZ CITY STAFF CITY MANAGER CITY ATTORNEY René Bobadilla Arnold M. Alvarez-Glasman DEPARTMENT HEADS Assistant City Manager Arlene Salazar Fire Chief Fernando Pelaez Police Chief Brad Keller Director of Finance Michael Solorza Director of Human Resources Nicholas Razo Director of Planning/Community Development Joseph Palombi Director of Public Works James Enriquez Director of Recreation and Community Services David Sosnowski Director of Transportation Young-Gi Kim Harabedian OPENING CEREMONIES 1. CALL MEETING TO ORDER: Mayor Melendez 2. ROLL CALL: City Clerk I. Barajas 1 In compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, if you need special assistance to participate in this meeting, please contact the Building Official at 323/887-1497. Notification 48 hours prior to the meeting will enable the City to make reasonable arrangements to ensure accessibility to this meeting. (28 CFR 35.102-35.104 ADA Title II1203). If you require translation services, please contact the City Clerk’s Office 24 hours before this meeting. Si necesita servicios de traducción, comuníquese con la Oficina del Secretario Municipal 24 horas antes de esta reunión. 1 3. STATEMENT OF PUBLIC ORAL COMMUNICATIONS FOR CLOSED SESSION ITEMS: Members of the public interested in addressing the City Council on any agenda item or topic must fill out a form provided at the door, and turn it in to the City Clerk prior to the beginning Oral communications. -

Chapter 11 Case No. 21-10632 (MBK) Judge

Case 21-10632-MBK Doc 449 Filed 07/23/21 Entered 07/23/21 18:07:04 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 79 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY In re: Chapter 11 L’OCCITANE, INC., Case No. 21-10632 (MBK) Debtor. Judge: Hon. Michael B. Kaplan CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I, Amanda L. Hinchey, depose and say that I am employed by Stretto, the claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned case. On July 19, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following documents to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A: • Cover Letter (Attached hereto as Exhibit C) • Order (I) Approving the Disclosure Statement on an Interim Basis; (II) Scheduling a Combined Hearing on Final Approval of the Disclosure Statement and Plan Confirmation and Deadlines Related Thereto; (III) Approving the Confirmation Hearing Notice; and (IV) Granting Related Relief (Docket No. 408) • First Amended Joint Plan of Reorganization of L’Occitane, Inc. and the Official Committee of Unsecured Creditors Pursuant to Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code (Docket No. 410) • First Amended Disclosure Statement for the First Amended Joint Plan of Reorganization of L’Occitane, Inc. and the Creditors’ Committee Pursuant to Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code (Docket No. 411) • Notice of (I) Interim Approval of Disclosure Statement, (II) Hearing to Consider Confirmation of Plan, and (III) Deadline for Filing Objections to Confirmation of Plan (Docket No. 415) [THIS SPACE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK] Case 21-10632-MBK Doc 449 Filed 07/23/21 Entered 07/23/21 18:07:04 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 79 Furthermore, on July 19, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following document to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit B: • Notice of (I) Interim Approval of Disclosure Statement, (II) Hearing to Consider Confirmation of Plan, and (III) Deadline for Filing Objections to Confirmation of Plan (Docket No. -

HCD Draft 2021-2029 Housing Element

HCD Draft 2021-2029 Housing Element City of Whittier 13230 Penn Street Whittier, CA 90602 Contact: Sonya Lui, Principal Planner [email protected] June 8, 2021 This page intentionally left blank. Table of Contents Page 1. introduction I1 overview I1 housing element scope and purpose I2 relationship to other general plan elements I2 public participation I3 2. community profile/housing need assessment N1 population and employment characteristics N1 stock characteristics N5 special housing needs N8 energy conservation opportunities N11 at-risk housing analysis N12 preservation and replacement options N12 projected housing need (RHNA) N13 3. constraints on housing production C1 non-governmental constraints C1 governmental constraints C3 4. housing resources R1 regional housing needs assessment R1 progress towards the RHNA R2 consistency with affirmatively furthering fair housing R15 5. 2014-2021 housing element program accomplishments A1 6. housing plan H1 goals and policies H2 implementing programs H4 summary of quantified objectives H15 appendix This page intentionally left blank. 1. introduction overview This Housing Element provides the City of Whittier with a coordinated and comprehensive strategy for promoting the production of safe, decent, and affordable housing for all community residents. Whittier has a strong commitment to implementing a vision that embraces new opportunities, supports housing development, and provides diverse housing options. Realizing that new housing opportunities for all income levels was challenging to achieve during the 5th Cycle, Whittier initiated a comprehensive General Plan update that rethinks residential development opportunities throughout the City. The General Plan update provides for a diversity of housing in a new Transit Oriented District, along Whittier Boulevard, in Uptown, and in expanded mixed-use districts. -

14316 CHRISTINE DR Whittier, CA 90605

14316 Christine Dr Whittier, CA 90605 OFFERING MEMORANDUM NON-ENDORSEMENT & DISCLAIMER NOTICE CONFIDENTIALITY & DISCLAIMER The information contained in the following Marketing Brochure is proprietary and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from Marcus & Millichap and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of Marcus & Millichap. This Marketing Brochure has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. Marcus & Millichap has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation, with respect to the income or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCB's or asbestos, the compliance with State and Federal regulations, the physical condition of the improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant's plans or intentions to continue its occupancy of the subject property. The information contained in this Marketing Brochure has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, Marcus & Millichap has not verified, and will not verify, any of the information contained herein, nor has Marcus & Millichap conducted any investigation regarding these matters and makes no warranty or representation whatsoever regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information provided. All potential buyers must take appropriate measures to verify all of the information set forth herein. -

Leasing Brochure

@FIGAT7TH DTLA FIGAT7TH.COM WELLS FARGO CENTER NORTH TOWER GAS COMPANY TOWER BANK OF AMERICA WELLS FARGO CENTER PLAZA SOUTH TOWER FIGUEROA AT HALO WILSHIRE 777 TOWER EY PLAZA TOWER 7TH ST. / METRO CENTER STATION FIGAT7TH 110 FREEWAY BROOKFIELD PROPERTIES ASSETS WHY DTLA? OVERVIEW 5.84 SQ. MILES $34 BILLION radius of DTLA invested in DTLA since 1999 1,000+ MOST ACCESSIBLE New Restaurants, Bars, Retail, Nightlife region in Greater Los Angeles linked and Amenities Opened from 2010-2019 by public transit/metro system STRONG MARKET DEMOGRAPHICS 80,000 $123,000 38 YRS Residents Residents Avg. HH Income Median Age of Residents 500,000 $122,000 41 YRS Weekday Population Workers Avg. HH Income Median Age of Workers BOOMING RESIDENTIAL MARKET 37,759 95% 4,829 29,338 Units Constructed Occupied in Units Under Units proposed Since 1999 Current Stock Construction TOURISM* 22 MILLION 1.6 MILLION $142 Total Number of Hotel Guests Average Daily Spend Visitors to DTLA Per Person in DTLA Source: Downtown Center Business Improvement District DTLA 2020 Survey & L.A. Tourism and Convention Board 2018 “ Every structure seems to house artists, musicians, designers, tech developers, chefs— the whole Who are the people in your neighborhood of the creative class. After decades of being all but forgotten, Downtown has approached a critical mass of cool...” GQ MAGAZINE 101 IN GOOD COMPANY CIVIC CENTER CITY WEST THE MUSIC BUNKER HILL CENTER WALT DISNEY GRAND DTLA HAS SO MUCH GRAND AV ARTS PARK BUNKER HILL CONCERT HALL CIVIC CENTER GRAND PARK TO OFFER THE BROAD 1 MOCA HOLLYWOOD WILSHIRE PASADENA HISTORIC FIGUEROA ST GRAND AVE EAST L.A. -

Case No. 17-42267-659 ) CHAPTER 11 PAYLESS HOLDINGS LLC, Et Al., ) ) Jointly Administered ) Debtors

Case 17-42267 Doc 997 Filed 06/07/17 Entered 06/07/17 18:43:26 Main Document Pg 1 of 16 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF MISSOURI EASTERN DIVISION In re: ) Case No. 17-42267-659 ) CHAPTER 11 PAYLESS HOLDINGS LLC, et al., ) ) Jointly Administered ) Debtors. ) Hearing Date: June 8, 2017 ) Hearing Time: 10:00 a.m. ) Hearing Location: Courtroom 7 North NOTICE OF REVISED SECOND LIST STORE CLOSINGS PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that on May 24, 2017, the debtors (the “Debtors”) in the above-captioned chapter 11 cases filed the Debtors’ Motion for Entry of an Order (I) Authorizing Second List Store Closings and (II) Granting Related Relief [Docket No. 883] (the “Motion”). PLEASE TAKE FURTHER NOTICE that, as further set forth in the Motion, the Debtors filed the Motion with the hope that continued negotiations between the date of filing of the Motion and the date of the hearing to consider the Motion would result in consensual modifications and rent concessions with respect to the Second List Stores.1 PLEASE TAKE FURTHER NOTICE that such negotiations have indeed resulted in a substantial number of consensual modifications and rent concessions, and as a result the Debtors are now seeking authority to close only 216 stores, rather than the 408 initially requested. As a result, the Debtors have removed 192 stores from the Second List Stores, as further set forth in the revised list of Second List Stores (the “Revised Second List Stores”) annexed hereto as “Exhibit A.” In addition, a redline of the Revised Second List Stores to the Second List Stores is annexed hereto as “Exhibit B.” 1 Capitalized terms used but undefined herein shall have the meanings ascribed to them in the Motion.