Violent Extremism and Insurgency in Bangladesh: a Risk Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odhikar's Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel

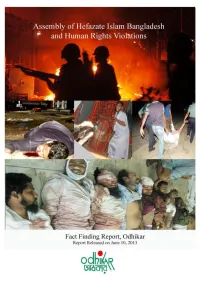

Odhikar’s Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel/Page-1 Summary of the incident Hefazate Islam Bangladesh, like any other non-political social and cultural organisation, claims to be a people’s platform to articulate the concerns of religious issues. According to the organisation, its aims are to take into consideration socio-economic, cultural, religious and political matters that affect values and practices of Islam. Moreover, protecting the rights of the Muslim people and promoting social dialogue to dispel prejudices that affect community harmony and relations are also their objectives. Instigated by some bloggers and activists that mobilised at the Shahbag movement, the organisation, since 19th February 2013, has been protesting against the vulgar, humiliating, insulting and provocative remarks in the social media sites and blogs against Islam, Allah and his Prophet Hazrat Mohammad (pbuh). In some cases the Prophet was portrayed as a pornographic character, which infuriated the people of all walks of life. There was a directive from the High Court to the government to take measures to prevent such blogs and defamatory comments, that not only provoke religious intolerance but jeopardise public order. This is an obligation of the government under Article 39 of the Constitution. Unfortunately the Government took no action on this. As a response to the Government’s inactions and its tacit support to the bloggers, Hefazate Islam came up with an elaborate 13 point demand and assembled peacefully to articulate their cause on 6th April 2013. Since then they have organised a series of meetings in different districts, peacefully and without any violence, despite provocations from the law enforcement agencies and armed Awami League activists. -

Charting a New Course: Women Preventing Violent Extremism

Charting a New Course I 2301 Constitution Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20037 www.usip.org © 2015 by the Endowment of the United States Institute of Peace. All rights reserved. First published 2015 To request permission to photocopy or reprint materials for course use, contact the Copyright Clearance Center at www.copyright.com. For print, electronic media, and all other subsidiary rights e-mail [email protected] Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standards for Information Science—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. II Charting a WOMEN PREVENTING VIOLENT EXTREMISM New Course 2 Acknowledgments 3 Introduction 7 Why Gender Matters 9 Women on the Front Lines by Alistair Millar 11 Exercise: Act Like a Woman/ Act Like a Man 12 Blindspots by Jayne Huckerby 13 Exercise: Spheres of Influence 15 Women and the Dynamics of Extremist Violence 17 Listen to the Women Activists by Sanam Naraghi-Anderlini 19 Exercise: Gendered Motivations 20 When Women are the Problem by Mia Bloom 21 Exercise: Multiple Interpretations: Who is Right? 22 Motivations of Female Fighters by Nimmi Gowrinathan 25 Engaging Communities in Preventing Violent Extremism 27 Building Resilience to Violent Extremism by Georgia Holmer 29 Exercise: Allies and Challengers 30 Charting New Ways with New Partners by Edit Schlaffer 31 Resource: Active Listening Techniques 32 Everyday Technologies Can Help Counter Violence and Build Peace by Nancy Payne 33 Resource: Enabling Technologies for Preventing Violent Extremism 34 Increasing Understanding through Words by Alison Milofsky 35 Resource: Debate versus Dialogue 36 Acronyms 36 Resources 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS he creation of the thought for action kit, “Charting a New Course: Women TPreventing Violent Extremism,” has been a team effort. -

In Their Own Words: Voices of Jihad

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CHILD POLICY a public service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY the public and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. in their own words Voices of Jihad compilation and commentary David Aaron Approved for public release; distribution unlimited C O R P O R A T I O N This book results from the RAND Corporation's continuing program of self-initiated research. -

The Birth of Al-Wahabi Movement and Its Historical Roots

The classification markings are original to the Iraqi documents and do not reflect current US classification. Original Document Information ~o·c·u·m·e·n~tI!i#~:I~S=!!G~Q~-2!110~0~3~-0~0~0~4'!i66~5~9~"""5!Ii!IlI on: nglis Title: Correspondence, dated 24 Sep 2002, within the General Military Intelligence irectorate (GMID), regarding a research study titled, "The Emergence of AI-Wahhabiyyah ovement and its Historical Roots" age: ARABIC otal Pages: 53 nclusive Pages: 52 versized Pages: PAPER ORIGINAL IRAQI FREEDOM e: ountry Of Origin: IRAQ ors Classification: SECRET Translation Information Translation # Classification Status Translating Agency ARTIAL SGQ-2003-00046659-HT DIA OMPLETED GQ-2003-00046659-HT FULL COMPLETED VTC TC Linked Documents I Document 2003-00046659 ISGQ-~2~00~3~-0~0~04~6~6~5~9-'7':H=T~(M~UI:7::ti""=-p:-a"""::rt~)-----------~II • cmpc-m/ISGQ-2003-00046659-HT.pdf • cmpc-mIlSGQ-2003-00046659.pdf GQ-2003-00046659-HT-NVTC ·on Status: NOT AVAILABLE lation Status: NOT AVAILABLE Related Document Numbers Document Number Type Document Number y Number -2003-00046659 161 The classification markings are original to the Iraqi documents and do not reflect current US classification. Keyword Categories Biographic Information arne: AL- 'AMIRI, SA'IO MAHMUO NAJM Other Attribute: MILITARY RANK: Colonel Other Attribute: ORGANIZATION: General Military Intelligence Directorate Photograph Available Sex: Male Document Remarks These 53 pages contain correspondence, dated 24 Sep 2002, within the General i1itary Intelligence Directorate (GMID), regarding a research study titled, "The Emergence of I-Wahhabiyyah Movement and its Historical Roots". -

Strategic Cooperation Between Japan and UNODC -The Joint Plan of Action

Strategic Cooperation between Japan and UNODC -The joint plan of action- The Government of Japan (hereafter referred to as Japan) and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (hereafter referred to as UNODC) have a long history of collaboration in countering illicit narcotic drugs, in crime prevention and criminal justice reform, as well as in countering terrorism. Japan has also been a leading provider of core support to the operations of UNODC. Japan and UNODC share mutual interest in further enhancing cooperation. During the first Strategic Policy Dialogue between Japan and UNODC, held in Yokohama on 2 June 2013 in the margins of the 5th Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD V), they identified regional, thematic and other areas for strategic cooperation, and developed a joint plan of action. They also agreed to hold Strategic Policy Dialogue at the senior level annually in Tokyo or Vienna (alternately). Japan and UNODC reviewed the progress of the implementation of the plan of action during the Strategic Policy Dialogue recently held, and amended it as follows. 1. Regional Cooperation (1) Africa Japan welcomes the participation of UNODC in the TICAD V in June 2013 and the TICAD VI in August 2016 in the TICAD process. Through the follow-up of TICAD VI, Japan and UNODC will enhance substantive and operational collaboration in Africa, in particular, in areas related to peace and security such as strengthening of criminal justice systems, countering transnational organized crime (illicit trafficking of narcotic drugs, firearms, and persons), corruption and cybercrime as well as combating terrorism, violent extremism and piracy. -

France 2016 International Religious Freedom Report

FRANCE 2016 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution and the law protect the right of individuals to choose, change, and practice their religion. The government investigated and prosecuted numerous crimes and other actions against religious groups, including anti-Semitic and anti- Muslim violence, hate speech, and vandalism. The government continued to enforce laws prohibiting face coverings in public spaces and government buildings and the wearing of “conspicuous” religious symbols at public schools, which included a ban on headscarves and Sikh turbans. The highest administrative court rejected the city of Villeneuve-Loubet’s ban on “clothes demonstrating an obvious religious affiliation worn by swimmers on public beaches.” The ban was directed at full-body swimming suits worn by some Muslim women. ISIS claimed responsibility for a terrorist attack in Nice during the July 14 French independence day celebration that killed 84 people without regard for their religious belief. President Francois Hollande condemned the attack as an act of radical Islamic terrorism. Prime Minister (PM) Manuel Valls cautioned against scapegoating Muslims or Islam for the attack by a radical extremist group. The government extended a state of emergency until July 2017. The government condemned anti- Semitic, anti-Muslim, and anti-Catholic acts and continued efforts to promote interfaith understanding through public awareness campaigns and by encouraging dialogues in schools, among local officials, police, and citizen groups. Jehovah’s Witnesses reported 19 instances in which authorities interfered with public proselytizing by their community. There were continued reports of attacks against Christians, Jews, and Muslims. The government, as well as Muslim and Jewish groups, reported the number of anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim incidents decreased by 59 percent and 58 percent respectively from the previous year to 335 anti-Semitic acts and 189 anti-Muslim acts. -

Bangladesh Jobs Diagnostic.” World Bank, Washington, DC

JOBS SERIES Public Disclosure Authorized Issue No. 9 Public Disclosure Authorized DIAGNOSTIC BANGLADESH Public Disclosure Authorized Main Report Public Disclosure Authorized JOBS DIAGNOSTIC BANGLADESH Thomas Farole, Yoonyoung Cho, Laurent Bossavie, and Reyes Aterido Main Report © 2017 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA. Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org. Some rights reserved This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the govern- ments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: Thomas Farole, Yoonyoung Cho, Laurent Bossavie, and Reyes Aterido. -

United Arab Emirates (Uae)

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: United Arab Emirates, July 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: UNITED ARAB EMIRATES (UAE) July 2007 COUNTRY اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴّﺔ اﻟﻤﺘّﺤﺪة (Formal Name: United Arab Emirates (Al Imarat al Arabiyah al Muttahidah Dubai , أﺑﻮ ﻇﺒﻲ (The seven emirates, in order of size, are: Abu Dhabi (Abu Zaby .اﻹﻣﺎرات Al ,ﻋﺠﻤﺎن Ajman , أ مّ اﻟﻘﻴﻮﻳﻦ Umm al Qaywayn , اﻟﺸﺎرﻗﺔ (Sharjah (Ash Shariqah ,دﺑﻲّ (Dubayy) .رأس اﻟﺨﻴﻤﺔ and Ras al Khaymah ,اﻟﻔﺠﻴﺮة Fajayrah Short Form: UAE. اﻣﺮاﺗﻰ .(Term for Citizen(s): Emirati(s أﺑﻮ ﻇﺒﻲ .Capital: Abu Dhabi City Major Cities: Al Ayn, capital of the Eastern Region, and Madinat Zayid, capital of the Western Region, are located in Abu Dhabi Emirate, the largest and most populous emirate. Dubai City is located in Dubai Emirate, the second largest emirate. Sharjah City and Khawr Fakkan are the major cities of the third largest emirate—Sharjah. Independence: The United Kingdom announced in 1968 and reaffirmed in 1971 that it would end its treaty relationships with the seven Trucial Coast states, which had been under British protection since 1892. Following the termination of all existing treaties with Britain, on December 2, 1971, six of the seven sheikhdoms formed the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The seventh sheikhdom, Ras al Khaymah, joined the UAE in 1972. Public holidays: Public holidays other than New Year’s Day and UAE National Day are dependent on the Islamic calendar and vary from year to year. For 2007, the holidays are: New Year’s Day (January 1); Muharram, Islamic New Year (January 20); Mouloud, Birth of Muhammad (March 31); Accession of the Ruler of Abu Dhabi—observed only in Abu Dhabi (August 6); Leilat al Meiraj, Ascension of Muhammad (August 10); first day of Ramadan (September 13); Eid al Fitr, end of Ramadan (October 13); UAE National Day (December 2); Eid al Adha, Feast of the Sacrifice (December 20); and Christmas Day (December 25). -

PERSPECTIVES on TERRORISM Volume 11, Issue 5

ISSN 2334-3745 Volume V, Issue 5 October 2017 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 11, Issue 5 Table of Contents Welcome from the Editors......................................................................................................1 Articles Countering Violent Extremism in Prisons: A Review of Key Recent Research and Critical Research Gaps.........................................................................................................................2 by Andrew Silke and Tinka Veldhuis The New Crusaders: Contemporary Extreme Right Symbolism and Rhetoric..................12 by Ariel Koch Exploring the Continuum of Lethality: Militant Islamists’ Targeting Preferences in Europe....................................................................................................................................24 by Cato Hemmingby Research Notes On and Off the Radar: Tactical and Strategic Responses to Screening Known Potential Terrorist Attackers................................................................................................................41 by Thomas Quiggin Resources Terrorism Bookshelf.............................................................................................................50 Capsule Reviews by Joshua Sinai Bibliography: Terrorist Organizations: Cells, Networks, Affiliations, Splits......................67 Compiled and selected by Judith Tinnes Bibliography: Life Cycles of Terrorism..............................................................................107 Compiled and selected by Judith -

Mass-Fatality, Coordinated Attacks Worldwide, and Terrorism in France

BACKGROUND REPORT Mass-Fatality, Coordinated Attacks Worldwide, and Terrorism in France On November 13, 2015 assailants carried out a series of coordinated attacks at locations in Paris, France, including a theater where a concert was being held, several restaurants, and a sporting event. These attacks reportedly killed more than 120 people and wounded more than 350 others. The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) claimed responsibility for the attack.1 To provide contextual information on coordinated, mass-fatality attacks, as well as terrorism in France and the attack patterns of ISIL, START has compiled the following information from the Global Terrorism Database (GTD).2 MASS-FATALITY TERRORIST ATTACKS Between 1970 and 2014, there have been 176 occasions on which terrorist Number of Times More than 100 People Were Killed attacks killed more than 100 people by Terrorist Attacks on a Single Day in a Single Country (excluding perpetrators), in a particular 30 country on a particular day. This includes both isolated attacks, multiple attacks, 25 and multi-part, coordinated attacks. The first such event took place in 1978, when 20 an arson attack targeting the Cinema Rex Theater in Abadan, Iran killed more than 15 400 people. Frequency Since the Cinema Rex attack, and until 10 2013, 4.2 such mass-fatality terrorist events happened per year, on average. In 5 2014, the number increased dramatically when 26 mass-fatality terrorist events 0 took place in eight different countries: Afghanistan (1), Central African Republic (1), Iraq (9), Nigeria (9), Pakistan (1), Source: Global Terrorism Database Year South Sudan (1), Syria (3), and Ukraine (1). -

Binary Framings, Islam and Struggle for Women's Empowerment In

Feminist Dissent Binary Framings, Islam and Struggle for Women’s Empowerment in Bangladesh Sohela Nazneen* Address *Correspondence: [[email protected]] Abstract In this paper, I investigate how binary framings of women’s identity have influenced struggles for women’s rights and the interpretations of the relationship between Islam and women’s empowerment in Bangladesh. These binary framings position women at opposite ends by dividing them between ‘Muslim/religious/moral/authentic/traditional’ or ‘Bengali/ secular/immoral/Westernised/ modern’. I trace the particular genealogies of these binary constructs which emerged during specific historical junctures and are influenced by the shifts in regional and international Peer review: This article politics. Drawing on primary research with women in religious political has been subject to a double blind peer review parties and women’s movement actors and newspaper reports, I provide process an account of how binary framings have been used by the Islamist actors and the counter framings used by the feminists to make claims over the state. I show how these framings have influenced the politics of © Copyright: The Authors. This article is representation of gender equality concerns, and reflect on what this means issued under the terms of the Creative Commons for possibilities of women’s empowerment and strategies for resistance. Attribution Non- Commercial Share Alike License, which permits use and redistribution of the work provided that Keywords: Bangladesh, women’s empowerment, gender, Islam, Hefazat the original author and source are credited, the work is not used for commercial purposes and that any derivative works are madentroduction available under the same license terms. -

Bangladesh Other Countries and Regions Monitored

BANGLADESH OTHER COUNTRIES AND REGIONS MONITORED KEY FINDINGS RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE U.S. GOVERNMENT In 2016, the frequency of violent and deadly attacks against religious minorities, secular bloggers, intellec- USCIRF recommends that the U.S. government should: tuals, and foreigners by domestic and transnational provide technical assistance and encourage the Ban- extremist groups increased. Although the government, gladeshi government to further develop its national led by the ruling Awami League, has taken steps to inves- counterterrorism strategy; urge Prime Minister Sheikh tigate, arrest, and prosecute perpetrators and increase Hasina and all government officials to frequently and publicly denounce religiously divisive language and acts protection for likely targets, the threats and violence of religiously motivated violence and harassment; assist have heightened the sense of fear among Bangladeshi the Bangladeshi government in providing local govern- citizens of all religious groups. In addition, illegal land ment officials, police officers, and judges with training on appropriations—commonly referred to as land-grab- international human rights standards, as well as how to bing—and ownership disputes remain widespread, investigate and adjudicate religiously motivated violent particularly against Hindus and Christians. Other con- acts; urge the Bangladeshi government to investigate cerns include issues related to property returns and the claims of land-grabbing and to repeal its blasphemy law; situation of Rohingya Muslims. In March 2016, a USCIRF and encourage the Bangladeshi government to continue staff member traveled to Bangladesh to assess the reli- to provide humanitarian assistance and a safe haven for gious freedom situation. Rohingya Muslims fleeing persecution in Burma. BACKGROUND the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).