Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPRING 2020, Vol. 34, Issue 1 SPRING 2020 1

SPRING 2020, Vol. 34, Issue 1 SPRING 2020 1 MISSION NAWJ’s mission is to promote the judicial role of protecting the rights of individuals under the rule of law through strong, committed, diverse judicial leadership; fairness and equality in the courts; and ON THE COVER 19 Channeling Sugar equal access to justice. Innovative Efforts to Improve Access to Justice through Global Judicial Leadership 21 Learning Lessons from Midyear Meeting in New Orleans addresses Tough Cases BOARD OF DIRECTORS ongoing challenges facing access to justice. Story on page 14 24 Life After the Bench: EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE The Honorable Sharon Mettler PRESIDENT 2 President's Message Hon. Bernadette D'Souza 26 Trial Advocacy Training for Parish of Orleans Civil District Court, Louisiana 2 Interim Executive Director's Women by Women Message PRESIDENT-ELECT 29 District News Hon. Karen Donohue 3 VP of Publications Message King County Superior Court, Seattle, Washington 51 District Directors & Committees 4 Q&A with Judge Ann Breen-Greco VICE PRESIDENT, DISTRICTS Co-Chair Human Trafficking 52 Sponsors Hon. Elizabeth A. White Committee Superior Court of California, Los Angeles County 54 New Members 5 Independent Immigration Courts VICE PRESIDENT, PUBLICATIONS Hon. Heidi Pasichow 7 Resource Board Profile Superior Court of the District of Columbia Cathy Winter-Palmer SECRETARY Hon. Orlinda Naranjo (ret.) 8 Global Judicial Leadership 419th District Court of Texas, Austin Doing the Impossible: NAWJ work with the Pan-American TREASURER Commission of Judges on Social Hon. Elizabeth K. Lee Rights Superior Court of California, San Mateo County IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT 11 Global Judicial Leadership Hon. Tamila E. -

2014 STUDENT EDITION INCLUDING OUTLINE and DISCUSSION TOPICS John R Berger

CHANGE OF VENUE CHANGE OF VENUE A LAW STUDIES TEXTBOOK INCLUDING THE TRUE STORY OF AN INDIANA TRIAL FOR TRIPLE MURDER 2014 STUDENT EDITION INCLUDING OUTLINE AND DISCUSSION TOPICS John R Berger 1 CHANGE OF VENUE Copyright 2008 by John R. Berger. [email protected] All rights reserved. This book or parts thereof may not be reproduced in any form without permission of the author. Published 2014 by Lake James Press 20 Lane 200H Lake James Angola IN 46703 NOTE: The page references below may not be correct due to scribd formatting. However, by downloading and selecting DOC, it should download in MS Works, the page references should be correct, and the document can be saved, edited, selected and printed. The entire materials in this textbook are available as a Survey of Law course in MS PowerPoint with narration as a free MOOC (Massive Open Online Course). To access the course go to or click on the following link http://www.coursesites.com/s/_LAW-INTRODUCTION Then click on Content. Then click on Change of Venue PowerPoint. Then click on Browse as a Guest to view and listen to the entire course. THE AUTHOR: John R. Berger is a graduate of Harvard Law School (JD 1953), Hillsdale College (BS Summa Cum Laude 1950), and a retired Circuit Court Judge and Professor of Law, Tri-State University. He is the author of a non fiction novel, The Red Gas Can, based upon the triple murder trial described in Change of Venue, and his autobiography, The Bubbles Rise. These books including Change of Venue are available in paperback at Amazon. -

Members by Circuit (As of January 3, 2017)

Federal Judges Association - Members by Circuit (as of January 3, 2017) 1st Circuit United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit Bruce M. Selya Jeffrey R. Howard Kermit Victor Lipez Ojetta Rogeriee Thompson Sandra L. Lynch United States District Court District of Maine D. Brock Hornby George Z. Singal John A. Woodcock, Jr. Jon David LeVy Nancy Torresen United States District Court District of Massachusetts Allison Dale Burroughs Denise Jefferson Casper Douglas P. Woodlock F. Dennis Saylor George A. O'Toole, Jr. Indira Talwani Leo T. Sorokin Mark G. Mastroianni Mark L. Wolf Michael A. Ponsor Patti B. Saris Richard G. Stearns Timothy S. Hillman William G. Young United States District Court District of New Hampshire Joseph A. DiClerico, Jr. Joseph N. LaPlante Landya B. McCafferty Paul J. Barbadoro SteVen J. McAuliffe United States District Court District of Puerto Rico Daniel R. Dominguez Francisco Augusto Besosa Gustavo A. Gelpi, Jr. Jay A. Garcia-Gregory Juan M. Perez-Gimenez Pedro A. Delgado Hernandez United States District Court District of Rhode Island Ernest C. Torres John J. McConnell, Jr. Mary M. Lisi William E. Smith 2nd Circuit United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Barrington D. Parker, Jr. Christopher F. Droney Dennis Jacobs Denny Chin Gerard E. Lynch Guido Calabresi John Walker, Jr. Jon O. Newman Jose A. Cabranes Peter W. Hall Pierre N. LeVal Raymond J. Lohier, Jr. Reena Raggi Robert A. Katzmann Robert D. Sack United States District Court District of Connecticut Alan H. NeVas, Sr. Alfred V. Covello Alvin W. Thompson Dominic J. Squatrito Ellen B. -

Circuit Circuit

December 2019 Featured In This Issue In Memoriam Randall Crocker, By Jeffrey Cole An Interview with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, By Hon. Elaine Bucklo TheThe A Historic Chief, By Steven J. Dollear An Interview with Judge Charles P. Kocoras, Editor’s Note By Jeffrey Cole A Life Well Lived: An Interview with Justice John Paul Stevens, By Jeffrey Cole and Elaine E. Bucklo CirCircuitcuit Appeals: The Classic Guide, By William Pannill John Paul Stevens: A True Gentleman of Justice, By Rachael D. Wilson Reversing the Magistrate Judge, By Jeffrey Cole Answering the Call, part 2: The Northern District of Illinois’ Rockford Bankruptcy Help Desk, By Laura McNally RiderRiderT HE J OURNALOFTHE S EVENTH In Recognition of Barbara Crabb, Comments By Diane P. Wood C IRCUITIRCUIT B AR A SSOCIATION Around the Circuit, By Collins T. Fitzpatrick J u d g e s The Circuit Rider In This Issue Letter from the President . 1 In Memoriam Randall Crocker, By Jeffrey Cole . 2 An Interview with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, By Hon. Elaine Bucklo . 3-12 A Historic Chief, By Steven J. Dollear . .13-15 An Interview with Judge Charles P. Kocoras, Editor’s Note By Jeffrey Cole . .16-28 A Life Well Lived: An Interview with Justice John Paul Stevens, By Jeffrey Cole and Elaine E. Bucklo . 29-38 Appeals: The Classic Guide, By William Pannill . .39-48 John Paul Stevens: A True Gentleman of Justice, By Rachael D. Wilson . 49-51 Reversing the Magistrate Judge, By Jeffrey Cole . 52-59 Answering the Call, part 2: The Northern District of Illinois’ Rockford Bankruptcy Help Desk, By Laura McNally . -

2019 Judicial Year in Review 2019 INDIANA JUDICIAL SERVICE REPORT JUDICIAL YEAR in REVIEW

Indiana Judicial Service Report HONORED TO SERVE 2019 Judicial Year in Review 2019 INDIANA JUDICIAL SERVICE REPORT JUDICIAL YEAR IN REVIEW The Supreme Court of Indiana The Honorable Loretta H. Rush, Chief Justice The Honorable Steven H. David The Honorable Mark S. Massa The Honorable Geoffrey G. Slaughter The Honorable Christopher M. Goff Justin P. Forkner, Chief Administrative Officer Office of Judicial Administration 251 North Illinois St., Ste. 1600 Indianapolis, IN 46204 Phone: (317) 232-2542 courts.in.gov ii | Judicial Year in Review ON THE COVER History of the Sullivan County Courthouse Sullivan County was named for Daniel Sullivan, American Revolutionary War hero and later the leader of the Vincennes area militia. The town of Carlisle was the county seat from 1816-1819. A log building in the town of Merom served as the courthouse from 1819 to 1842. The City of Sullivan became the county seat in 1843. The Sullivan County courthouse has been located in the center of the downtown city square in Sullivan since 1843. The construction of the current courthouse began in 1926 and was completed in 1928. The courthouse was built in the Beau Arts architectural style by architect John Bayard and builder Walter Heath. John Bayard was also the architect of the Vermillion County Courthouse, and the Sullivan County Courthouse and the Vermillion County Courthouse are nearly identical in style. It was the conscious choice of the Sullivan County Commissioners to construct the courthouse in Sullivan based on the design of the Vermillion County Courthouse, which had been completed in 1924. The Sullivan County Courthouse is nearly square, constructed with a steel frame and concrete. -

Women in Leadership

1 Women in Leadership Women in Leadership and Their Influence on Rural Community Development by Christina Pearison Final Project Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Leadership Development Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College August 22, 2020 Women in Leadership 2 Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College Graduate Program in Leadership Development Date: August_22, 2020__ We hereby recommend that the Final Project submitted by: Christina Pearison Entitled: Women in Leadership and Their Influence on Rural Community Development Be accepted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Leadership Development. Advisory Committee: __8/27/2020_ _Jennie Mitchell, Ph.D._________________ date __9/01/2020__ Lamprini Pantazi, Ph.D.______ date We certify that in this Final Project all research involving human subjects complies with the Policies and Procedures for Research involving Human Subjects, Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College, Saint Mary-of-the-Woods, Indiana 47876 Women in Leadership 3 Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................................. 5 The Mission ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 The Vision ......................................................................................................................................................... -

United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

Case: 10-3903 Document: 34 Filed: 08/16/2011 Pages: 23 In the United States Court of Appeals For the Seventh Circuit No. 10-3903 LADY DI’S, INC., Plaintiff-Appellant, v. ENHANCED SERVICES BILLING, INC. AND ILD TELECOMMUNICATIONS, INC. d/b/a ILD TELESERVICES, INC., Defendants-Appellees. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana, Indianapolis Division. No. 1:09-cv-00340-SEB-DML—Sarah Evans Barker, Judge. ARGUED MAY 11, 2011—DECIDED AUGUST 16, 2011 Before ROVNER and HAMILTON, Circuit Judges, and LEFKOW, District Judge. HAMILTON, Circuit Judge. Plaintiff Lady Di’s, Inc. alleged in this proposed class action that defendants Enhanced The Honorable Joan Humphrey Lefkow of the Northern District of Illinois, sitting by designation. Case: 10-3903 Document: 34 Filed: 08/16/2011 Pages: 23 2 No. 10-3903 Services Billing, Inc. (“ESBI”) and ILD Telecommunica- tions, Inc. are billing aggregators engaged in “cramming” by placing unauthorized charges on customers’ tele- phone bills. The plaintiff alleged that the defendants arranged to have unauthorized charges placed on its telephone bill and, in the six years before this suit was filed, have been responsible for unauthorized charges being placed on the telephone bills of more than one million Indiana telephone numbers. The complaint alleged that plaintiff “never requested, authorized, or even knew about” the services for which defendants charged it. The evidence, however, turned out differently. Both defendants produced evidence proving that the plaintiff actually ordered the services in question. Despite that evidence, plaintiff has pursued the case, arguing that although it actually ordered the services, the charges were never properly authorized. -

Judge Sarah Evans Barker

March 29, 2015 Women quietly do extraordinary things every day. To help shed light on the resilience and strength of Hoosier women and celebrate their accomplishments and contributions to history we are releasing an article every day in the month of March. These articles showcase how women have moved Indiana and our country forward and who inspire others to do great things in their own lives. Women in Indiana have an important role to play. You can make a difference by: . Learning more about the issues affecting women in Indiana. Voicing your opinion on issues important to you Judge Sarah Evans Barker . Serving as an advocate for women Judge Sarah Evans Barker became the first female federal judge in Indiana . Mentoring another woman when she was appointed to the United States District Court, Southern . Join ICW’s mailing list or social media outlets to be notified of upcoming events, District of Indiana, in March 1984 and served as chief judge between 1994 programs and resources available to and 2001. Prior to her appointment, Judge Barker was United States women Attorney for the Southern District of Indiana. From 1977 to 1981, she was both an associate and partner at the Indianapolis law firm of Bose, Go to www.in.gov/icw to learn more about McKinney & Evans. She started her Indianapolis legal career as an assistant the Indiana Commission for Women and their current initiatives. United States Attorney, after working as a legislative assistant to Senator Charles H. Percy and Congressman Gilbert Gude in Washington, D.C., and special counsel to the Senate Government Operations Subcommittee. -

JUDICIAL HONORS Commission Dates This Spring

Published by the Bolch Judicial Institute at Duke Law. Reprinted with permission. © 2021 Duke University School of Law. All rights reserved. JUDICATURE.DUKE.EDU BRIEFS6 VOL. 101 NO. 1 MILESTONES These federal judges (active status) are celebrating milestone anniversaries of their JUDICIAL HONORS commission dates this spring. Senior Judge MICHAEL M. BAYLSON Article III judge. Justice Elena Kagan Kuehn teaches evidence workshops at years of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern chaired the selection committee. her alma mater, the University of Tulsa. 35 District of Pennsylvania received the ELIZABETH ANNE KOVACHEVICH James Wilson Award from the University Genesee County Family Court Judge Elon Law School honored PATRICIA U.S. District Court, of Pennsylvania Law School in honor of DUNCAN M. BEAGLE received the TIMMONS-GOODSON, a former North Middle District of Florida a lifetime of service to the legal profes- Daniel J. Wright Lifetime Achievement Carolina Supreme Court associate sion. Judge Baylson has served on the Award for his service to Michigan’s justice and vice chair of the U.S. years bench since 2002; he previously served children. He has been on the bench in Commission on Civil Rights, with its 25 in private practice and as a U.S attorney. Flint, Michigan, for more than 25 years Leadership in the Law Award. STEVEN D. MERRYDAY U.S. District Court, and has worked to improve Michigan’s Middle District of Florida Criminal District Court Judge MARC child support enforcement system and The Nebraska Supreme Court honored KEVIN M. MOORE C. CARTER of Harris County, Texas, legislation relating to foster children. -

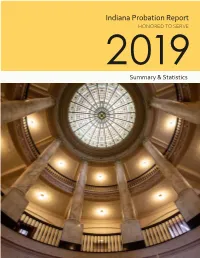

2019 Probation Summary & Statistics

Indiana Probation Report HONORED TO SERVE 2019 Summary & Statistics 2019 INDIANA PROBATION REPORT SUMMARY & STATISTICS The Supreme Court of Indiana The Honorable Loretta H. Rush, Chief Justice The Honorable Steven H. David The Honorable Mark S. Massa The Honorable Geoffrey G. Slaughter The Honorable Christopher M. Goff Justin P. Forkner, Chief Administrative Officer Office of Judicial Administration 251 North Illinois St., Ste. 1600 Indianapolis, IN 46204 Phone: (317) 232-2542 courts.in.gov ii | Indiana Probation Report ON THE COVER History of the Sullivan County Courthouse Sullivan County was named for Daniel Sullivan, American Revolutionary War hero and later the leader of the Vincennes area militia. The town of Carlisle was the county seat from 1816-1819. A log building in the town of Merom served as the courthouse from 1819 to 1842. The City of Sullivan became the county seat in 1843. The Sullivan County courthouse has been located in the center of the downtown city square in Sullivan since 1843. The construction of the current courthouse began in 1926 and was completed in 1928. The courthouse was built in the Beau Arts architectural style by architect John Bayard and builder Walter Heath. John Bayard was also the architect of the Vermillion County Courthouse, and the Sullivan County Courthouse and the Vermillion County Courthouse are nearly identical in style. It was the conscious choice of the Sullivan County Commissioners to construct the courthouse in Sullivan based on the design of the Vermillion County Courthouse, which had been completed in 1924. The Sullivan County Courthouse is nearly square, constructed with a steel frame and concrete. -

Message from the Dean

cover 12/19/07 1:58 PM Page 1 cover 12/19/07 1:58 PM Page 2 Message From the Dean Dear Alumni and Friends, My first semester as Dean of the IU School of Law-Indianapolis is coming to a close. It has been a hectic and exhilarating six months! As I have mentioned before, we have a great school—and the longer I am here, the more convinced I am that we have the potential to be one of the finest institutions of legal education in the country. As you read the articles in this magazine/dean’s report, you will see that our school is involved in some very exciting initiatives. You will read about our LL.M. program creating new campuses in Egypt, and you will learn about our many students, faculty and alumni who are making a significant impact, not just in Indiana, but across the country and around the world. I hope you will take the time to read about the many programs that have taken place at the school so far this year—such as this fall’s Conference on Relations Between Congress and the Federal Courts, which featured U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito—the fourth Supreme Court Justice to visit Inlow Hall since its dedication in 2001 and the second in the span of five months. Recently I spent a fair amount of time comparing our financial status with that of other Big Ten law schools, and I have to tell you that it is quite astonishing that our school has been able to maintain its reputation and high quality of programs given that we rank dead last in virtually every financial metric among Big Ten schools. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

In the United States Court of Appeals For the Seventh Circuit No. 12-1232 PRESTWICK CAPITAL MANAGEMENT, LTD., PRESTWICK CAPITAL MANAGEMENT 2, LTD., PRESTWICK CAPITAL MANAGEMENT 3, LTD., Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. PEREGRINE FINANCIAL GROUP, INC., Defendant-Appellee. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division. No. 1:10-CV-00023—Elaine E. Bucklo, Judge. ARGUED JANUARY 24, 2013—DECIDED JULY 19, 2013 Before MANION and WOOD, Circuit Judges, and BARKER, District Judge. BARKER, District Judge. Author-cum-rabbi Chaim Potok once observed that life presents “absolutely no guarantee The Honorable Sarah Evans Barker, United States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana, sitting by designation. 2 No. 12-1232 that things will automatically work out to our best advan- tage.”1 Given the regulatory mandate that certain financial entities guarantee other entities’ performance, and acknowledging that guarantees of all sorts can turn out to be ephemeral, we grapple here with the truth of Potok’s aphorism. More specifically, the instant lawsuit requires us to clarify the scope of a futures trading “guar- antee gone wrong,” presenting sunk investments and semantic distractions along the way. In 2009, Prestwick Capital Management Ltd., Prestwick Capital Management 2 Ltd., and Prestwick Capital Man- agement 3 Ltd. (collectively, “Prestwick”) sued Peregrine Financial Group, Inc. (“PFG”), Acuvest Inc., Acuvest Brokers, LLC, and two of Acuvest’s principals (John Caiazzo and Philip Grey), alleging violations of the Com- modity Exchange Act (“CEA”), 7 U.S.C. § 1 et seq. Prestwick asserted a commodities fraud claim against all defendants, a breach of fiduciary duty claim against the Acuvest defendants, and a guarantor liability claim against PFG.