Recoveries and Reclamations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A HISTORY of CLUB CRICKET in COUNTY DURHAM Chapter One

A HISTORY OF CLUB CRICKET IN COUNTY DURHAM Chapter One..........The eighteenth century In the beginning The first recorded cricket match in Durham was at Raby Castle in 1751. It was five years after the Duke of Cumberland and bayoneted Redcoats slogged through the county’s mud on their way to the Battle of Culloden. Defoe’s account of his travels through Great Britain had not long been published. Defoe found nothing remarkable in Darlington or Chester-le-Street except “dirt” but was impressed by Lumley Castle and acknowledged Lumley coal the best in the country. He thought Durham a “compact neatly contriv’d city” where clergy lived “in all the splendour and magnificence imaginable”. Durham cathedral and Saint Cuthbert’s remains were a shrine for pilgrims but the city was a vulnerable haven riding on a cut-throat sea. The poor lived in slums; the populace was prey to vagabonds, footpads and highwaymen. The Bishop of Durham bewailed “the scorn of religion”. His flock scratched a living on the land or burrowed beneath it for lead and coal; their leisure centred upon drinking and blood sports like cock-fighting. In 1742 John Wesley came across a village “inhabited by colliers only, and as such had been always in the first rank for savage ignorance, and wickedness of every kind. Their grand assembly used to be on the Lord’s Day on which men, women and children met together to dance, fight, curse, and swear, and play chuck-ball, span farthing, or whatever came to hand.” Somehow, sometime the game of cricket took root in these parts. -

Abandoned Mines and the Water Environment

Abandoned mines and the water environment Science project SC030136-41 Product code: SCHO0508BNZS-E-P The Environment Agency is the leading public body protecting and improving the environment in England and Wales. It’s our job to make sure that air, land and water are looked after by everyone in today’s society, so that tomorrow’s generations inherit a cleaner, healthier world. Our work includes tackling flooding and pollution incidents, reducing industry’s impacts on the environment, cleaning up rivers, coastal waters and contaminated land, and improving wildlife habitats. This report is the result of research commissioned and funded by the Environment Agency’s Science Programme. Published by: Author(s): Environment Agency, Rio House, Waterside Drive, Dave Johnston Aztec West, Almondsbury, Bristol, BS32 4UD Hugh Potter Tel: 01454 624400 Fax: 01454 624409 Ceri Jones www.environment-agency.gov.uk Stuart Rolley Ian Watson ISBN: 978-1-84432-894-9 Jim Pritchard © Environment Agency – August 2008 Dissemination Status: Released to all regions All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced Publicly available with prior permission of the Environment Agency. Keywords: The views and statements expressed in this report are Minewater, abandoned mine, Coal Authority, Water those of the author alone. The views or statements Framework Directive, non-coal mine expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of the Environment Agency and the Environment Agency’s Project Manager: Environment Agency cannot accept any responsibility for Dave Johnston –Ty Cambria, Cardiff such views or statements. Collaborator(s): This report is printed on Cyclus Print, a 100% recycled Coal Authority stock, which is 100% post consumer waste and is totally Scottish Environment Protection Agency chlorine free. -

Stanley Activity and Support Information Directory

Stanley Activity and Support Information Directory Altogether better Durham Spring 2019 Stanley 5th Edition Area Action Partnership www.durham.gov.uk/stanleyaap Welcome to the fifth edition of the Stanley Activity and Support Information Directory There is a wide variety of activities such as Coffee Mornings, Boot Camps, Carpet Bowls, Ladies Clubs, Football Clubs, Men’s Clubs, and much more, which you can get involved in. Information about local organisations that provide support and advice to local residents is also included for your reference. We hope you’ll enjoy the booklet and find an activity that suits you. 2 Altogether better Durham Stanley Area Action Partnership What is an Area Action Partnership? Area Action Partnerships, or AAPs for short, are a way for you to get involved in the work of Durham County Council (DCC), Stanley Town Council, Karbon Homes, Health Service, Durham Police, the Fire & Rescue Service, local businesses and the Voluntary and Community Sector, placing you at the heart of local decision making. There are 14 AAPs throughout County Durham and they work with you to identify and address your local issues and improve the area you live in, its services, its facilities and its appearance. The Priorities for 2019/20 for Stanley AAP are: 4 Stronger Stanley – Children Young People & Families and Community Safety 4 Supporting Stanley – Older People and Health & Wellbeing 4 Successful Stanley – Employment, Enterprise and Training If you would like to come along to our monthly task group meetings or just receive our monthly e-bulletin keeping you up to date with local news, please get in touch. -

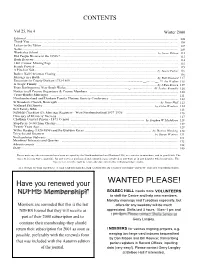

Have You Renewed Your NDFHS Membership? WANTED PLEASE!

CONTENTS Vol 25, No 4 Winter 2000 Editorial ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 106 Thank You .................................................................................................................................................................................... 106 Letters to the Editor .................................................................................................................................................................... 107 News ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 109 Waskerley School .............................................................................................................................................. by Joyce Wilson 112 Did People Divorce in the 1850's? ............................................................................................................................................ 113 Book Reviews .............................................................................................................................................................................. 114 1861 Census: Missing Page ........................................................................................................................................................ 115 French Proverb -

Recoveries and Reclamations

Advances in Art & Urban Futures Volume 2 Recoveries and Reclamations Edited by Judith Rugg Daniel Hinchcliffe Advances in Art & Urban Futures Volume 2 Recoveries and Reclamations intellect TM BRISTOL, ENGLAND PORTLAND, OR, USA Edited by Judith Rugg and Daniel Hinchcliffe First Published in Hardback 2002 by Intellect Books, PO Box 862,Bristol, BS99 1DE, UK First Published in USA in 2002 by Intellect Books, ISBS, 5824 Hassalo St, Portland, Oregon 97213-3644, USA Copyright ©2002 Intellect Ltd All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission. Consulting Editor: Masoud Yazdoni Book and Cover Design: Joshua Beadon – Toucan Copy Editor: Holly Spradling Set in Joanna A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Electronic ISBN 1-84150-828-4 / ISBN1-84150-055-0 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Cromwell Press,Wiltshire Contents Series Introduction 5 Malcolm Miles Foreword 7 Jane Rendell General Introduction 11 Judith Rugg and Daniel Hinchcliffe Contributors 15 Section One – Issues of Regeneration and Cultural Change Regenerating Public Life? A Sensory Analysis of Regenerated 19 Public Places in El Raval, Barcelona Monica Degen Utopia from Dystopia: 37 TheWomens PlayhouseTrust and theWapping Project Judith Rugg New Urban Spaces: 49 Regenerating a Design Ethos PaulTeedon Section Two – Artists’ Reclamations/Ecological Spatial Actions Art, -

Skilled! Report, Guidance & Materials on Basic Skills & Youth Work

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 427 179 CE 078 048 AUTHOR Merton, Bryan TITLE Skilled! Report, Guidance & Materials on Basic Skills & Youth Work. INSTITUTION Community Education Development Centre, Coventry (England). SPONS AGENCY National Literacy Trust, London (England). ISBN ISBN-0-947607-41-2 PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 47p. AVAILABLE FROM Community Education Development Centre, Woodway Park School, Wigston Road, Coventry CV2 2RH, England, United Kingdom (7.95 British pounds plus 80 pence postage). PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055)-- Reports Evaluative (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; *Basic Skills; Demonstration Programs; Disadvantaged Youth; Education Work Relationship; Employment Potential; Foreign Countries; *Integrated Curriculum; *Literacy Education; National Programs; Nonformal Education; Numeracy; Partnerships in Education; *Program Effectiveness; School Business Relationship; *Work Experience Programs; Youth Employment; *Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS *England ABSTRACT This document includes materials from and about Skilled!, a national demonstration project that was implemented in 10 areas of England in partnership with local authority youth services and further education colleges to provide educational opportunities for disaffected and underachieving young people aged 16 and over. The first half of the document is a project evaluation that explains how more than 200 young people participated in the project, which sought to develop basic skills through youth work and informal learning, featured a recruitment and delivery style adopted from youth work approaches, and integrated basic skills instruction into youth work activities. The evaluation report covers the following topics: the Skilled! initiative, publicity and recruitment, young people's special needs, assessment outcomes, resources, accreditation, positive and negative factors, support, case studies, and young people's writing.