Salpingectomy for Ovarian Cancer Prevention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When to Consider Tubal Reversal Vs IVF Success Rates Point to Greater Outcomes with IVF for Women in Their Mid-Thirties and Older

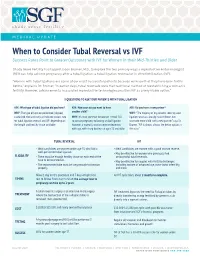

MEDICAL UPDATE When to Consider Tubal Reversal vs IVF Success Rates Point to Greater Outcomes with IVF for Women in their Mid-Thirties and Older Shady Grove Fertility has tapped Jason Bromer, M.D., to explore the two primary ways a reproductive endocrinologist (REI) can help achieve pregnancy after a tubal ligation: a tubal ligation reversal or in vitro fertilization (IVF). "Women with tubal ligations are some of our most successful patients because we know that they have been fertile before," explains Dr. Bromer. "In earlier days, tubal reversals were the traditional method of reestablishing a woman’s fertility. However, advancements in assisted reproductive technologies position IVF as a very viable option." 3 QUESTIONS TO ASK YOUR PATIENTS WITH TUBAL LIGATION ASK: What type of tubal ligation did you have? ASK: How soon do you want to have ASK: Do you have a new partner? WHY: The type of ligation performed (clipped, another child? WHY: "The majority of my patients seeking tubal cauterized, tied and cut) can indicate success rate WHY: It’s most common for women in their 30s ligation reversals already have children, but for tubal ligation reversal and IVF, depending on to pursue pregnancy following a tubal ligation. want one more child with a new partner," says Dr. the length and healthy tissue available. However, a woman’s ovarian reserve decreases Bromer. "IVF is almost always the better option in with age, with sharp declines at ages 35 and older. this case." TUBAL REVERSAL IVF • Ideal candidates are women under age 35 who had a • Ideal candidates are women with a good ovarian reserve. -

Successful Pregnancies After Removal of Intratubal Microinserts

2. Tonni G, De Felice C, Centini G, Ginanneschi C. Cervical and 5. Levine AB, Alvarez M, Wedgwood J, Berkowitz RL, Holzman oral teratoma in the fetus: a systematic review of etiology, I. Contemporary management of a potentially lethal fetal pathology, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Arch Gynecol anomaly: a successful perinatal approach to epignathus. Obstet Obstet 2010;282:355–61. Gynecol 1990;76:962–6. 3. Calda P, Novotna M, Cutka D, Brestak M, Haslik L, Goldova 6. Berrington JE, Stafford FW, Macphail S. Emergency EXIT for B, et al. A case of an epignathus with intracranial extension preterm labour after FETO. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed appearing as a persistently open mouth at 16 weeks and 2010;95:F376–7. subsequently diagnosed at 20 weeks of gestation. J Clin Ultra- 7. Hedrick HL, Flake AW, Crombleholme TM, Howell LJ, sound 2011;39:164–8. Johnson MP, Wilson RD, et al. The ex utero intrapartum 4. Marwan A, Crombleholme TM. The EXIT procedure: principles, therapy procedure for high-risk fetal lung lesions. J Pediatr pitfalls, and progress. Semin Pediatr Surg 2006;15:107–15. Surg 2005;40:1038–44. Successful Pregnancies After and who would like to conceive have two options: in vitro fertilization and sterilization reversal. Successful Removal of Intratubal Microinserts pregnancies resulting from in vitro fertilization after intratubal microinsert sterilization have been described.2 Charles W. Monteith, MD, Based on a literature search of the entire PubMed and Gary S. Berger, MD, MPH database up to August 2011 (using the key words “Essure” and “pregnancy”), these are the first two re- BACKGROUND: Patients with intratubal microinsert ports of successful pregnancy after surgical outpatient sterilization later may request reversal. -

Monash Health Referral Guidelines – Gynaecology

Monash Health Referral Guidelines (Incorporating Statewide Referral Criteria) GYNAECOLOGY EXCLUSIONS Services not offered In Vitro Fertilisation by Monash Health CONDITIONS CONTRACEPTIVE COUNSELLING MENSTRUAL MANAGEMENT Contraception Persistent, heavy menstrual bleeding Pregnancy Choices Bartholin's cysts / vaginal lesions Post-Menopausal bleeding Post-Coital bleeding DYSPLASIA Persistent or unexplained intermenstrual Dysplasia/Abnormal Cervical bleeding Screening Test Fibroids Vulval ulcers Vulval disorders PELVIC FLOOR/UROGYNAECOLOGY Genital warts Pelvic organ prolapse Urinary incontinence Recurrent UTI’s GYNAECOLOGY ENDOSCOPY Ovarian and other adnexal pathology Dyspareunia REPRODUCTIVE MEDICINE Pelvic Inflammatory disease Infertility Persistent pelvic pain Amenorrhea Male infertility Recurrent miscarriages GYNAECOLOGY ONCOLOGY Tubal & vasectomy reversal Cancer of the cervix Endocrine problems (Polycystic Ovarian cancer Ovarian Syndrome) Gynae cancers -suspected and confirmed SEXUAL MEDICINE & THERAPY CLINIC Sexual & relationship counselling MENOPAUSE Turner 's Syndrome Cancer and menopause PAEDIATRIC & ADOLESCENT GYNAE Premature menopause Paediatric and Adolescent Gynaecology General menopause ENDOMETRIOSIS Endometriosis Head of unit: Program Director: Last updated: Professor Beverley Vollenhoven Associate Professor Ryan Hodges 06/02/2020 Monash Health Referral Guidelines (Incorporating Statewide Referral Criteria) GYNAECOLOGY PRIORITY For emergency cases please do any of the following: EMERGENCY - send the patient to the Emergency -

A Personal Choice with Dr. Monteith Where Permanent

A Personal Choice With Dr. Monteith Where Permanent THE MAGAZINE Is Not Forever FOR HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS A Personal Choice with Dr. Monteith Specializing in Male and Female Sterilization Reversal and No-Needle No-Scalpel Vasectomy Women and men travel across the United Many within the medical community re- The new practice name is a reflection of States and around the world to A Personal call the practice when it was Chapel Hill the broader vision, says Dr. Monteith. “Our Choice of Raleigh, a unique practice dedi- Tubal Reversal Center, founded by Gary S. new name may not be understandable to cated to outpatient, minimally invasive Berger, M.D. Dr. Monteith joined Dr. Berger the general public but for those who seek sterilization and sterilization reversal ser- there in 2008, and together they provided our services the immense meaning of our vices in a state-of-the-art facility. a unique form of tubal ligation reversal name is readily apparent,” he says. that allows faster patient recovery, avoids The surgical specialty practice exclusively prolonged hospitalization and decreases A Personal Choice is conveniently located offers tubal ligation reversal, and vasec- patient recovery time. near North Hills Mall and Midtown Raleigh, tomy and vasectomy reversal. Tubal rever- so patients can stay in one of the nearby sal and vasectomy reversal have proven to After Dr. Berger retired in 2013, Dr. Monte- luxury hotels and walk to many restaurants be more effective and are more affordable ith expanded on his health care vision by and entertainment venues. The area also than alternative treatments, and vasectomy giving male patients greater reproductive provides closer access to Raleigh Durham is safer than tubal ligation. -

Post Sterilization Tuboplasty: Boon Or Bain !

Indian Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Case Report 107 Volume 5 Number 1, January - March 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21088/ijog.2321.1636.5117.19 Post Sterilization Tuboplasty: Boon or Bain ! Mukti S. Harne*, Sumedha Harne**, Urmila Gavali*** Abstract fertilization for the next pregnancy, leading to compulsion on women to undergo tubal reversal. The incidence of a successful India is developing country, yet pregnancy after tubal ligation is 40%. There the development is less in the are many predisposing factors for the success medical sector. Though the of the pregnancy like the tubal length after awareness of tubal ligation is vividly surgery should be >4 cm, absence of present in the rural set up, pressure hydrosalpingnx and previous birth within on females are increasing due to 5 years [1]. preference of male child in the society. Some unfortunate We, at our institution encountered, an circumstances, may it be pressure unfortunate case of a couple, with history of from the family members or secondary infertility and belonging to the unfortunate death of the existing muslim community, who were anxious to children or poor economic status of conceive since 3 years and weren’t the family to afford the In vitro investigated previously. This 24 years, fertilization for the next pregnancy, Shabana Shaikh, P1D1, housewife by leading to compulsion on women to occupation and resident of Ahmednagar, undergo tubal reversal. Hence, this came with her husband in the gynaec opd. case was brought to notice,while Detailed history of the couple was taken . emphasis was laid on the surgical Her menstrual history was regular, management of a case that we monthly interval, soaking 1-2 pads per day, managed. -

Tubal Ligation Reversal (English)

Tubal Ligation Reversal What is tubal ligation reversal? Tubal ligation reversal is an operation that may be done in some cases after you have had tubal sterilization. Tubal sterilization, also called tubal ligation or having your tubes tied, is a permanent way to prevent pregnancy by surgically closing a woman's fallopian tubes. It is considered to be a permanent type of birth control. Normally, the fallopian tubes carry the eggs from the ovaries to the uterus. Tubal ligation closes the tubes by cutting, tying, clipping, or burning the tubes, or by plugging the opening of the tubes. It prevents pregnancy because it stops sperm from reaching and fertilizing eggs after you have sex. It also prevents eggs from reaching the inside of the uterus (womb). Tubal ligation reversal is an operation to try to reconnect or unblock the fallopian tubes so that you may be able to get pregnant again, naturally. Tubal ligation reversal is difficult, expensive, and often not successful. Health insurance may not cover the cost. Talk to your healthcare provider to see if this procedure is right for you. When is this procedure used? If you decide that you want to become pregnant again after sterilization, having surgery to reverse tubal ligation is one way that might make this possible. It does not always work, but it may be less expensive than other procedures. If it is successful, you will not likely need any other treatments to have more children. Another way to try to get pregnant after sterilization is assisted reproduction technology (ART). When ART is done, eggs are removed from your body and fertilized with the father’s sperm in a lab. -

2009 Nhamcs Micro-Data File Documentation Page 1

2009 NHAMCS MICRO-DATA FILE DOCUMENTATION PAGE 1 ABSTRACT This material provides documentation for users of the public use micro-data files of the 2009 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS). NHAMCS is a national probability sample survey of visits to hospital outpatient and emergency departments, conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The survey is a component of the National Health Care Surveys, which measure health care utilization across a variety of health care providers. There are two micro-data files produced from NHAMCS, one for outpatient department records and one for emergency department records. Section I of this documentation, “Description of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey,” includes information on the scope of the survey, the sample, field activities, data collection procedures, medical coding procedures, and population estimates. Section II provides detailed descriptions of the contents of each file’s data record by location. Section III contains marginal data for selected items on each file. The appendixes contain sampling errors, instructions and definitions for completing the Patient Record forms, and lists of codes used in the survey. PAGE 2 2009 NHAMCS MICRO-DATA FILE DOCUMENTATION SUMMARY OF CHANGES FOR 2009 The 2009 NHAMCS Emergency Department and Outpatient Department public use micro-data files are, for the most part, similar to the 2008 files, but there are some important changes. These are described in more detail below and reflect changes to the survey instrument, the Patient Record form. Emergency Departments 1. New or Modified Items a. In item 1, Patient Information, there is a new checkbox item “Arrival by Ambulance.” This replaces the 2008 item, “Mode of Arrival.” b. -

BIRTH and GROWTH MEDICAL JOURNAL Year 2019, Vol XXVIII, Suplemento II

Birth and Growth Medical Journal CMIN SUMMIT’19 2019 Desafios da Doença Crónica Resumo das Comunicações Suplemento II Suplemento NASCER E CRESCER BIRTH AND GROWTH MEDICAL JOURNAL year 2019, vol XXVIII, Suplemento II PEDIATRIA COMUNICAÇÕES ORAIS PED_0219 PED_0319 ATTENTION DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVITY SYMPTOMS AND LEFT VENTRICULAR NONCOMPACTION IN A PEDIATRIC SLEEP HABITS AMONG PRESCHOOLERS: POPULATION IS THERE AN ASSOCIATION? Cláudia João LemosI, Filipa Vila CovaII, Isabel SáIII, Sílvia AlvaresII Rita GomesI, Bebiana SousaI, Diana GonzagaII, Marta RiosIII, Catarina PriorII, Inês Vaz MatosII Introduction: Left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC) is a rare congenital cardiomyopathy (CMP) characterized by presence of Introduction: Sleep-related problems and complaints are prevalent prominent ventricular myocardial trabeculations in absence of among children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). other structural heart defects. This CMP has a heterogeneous Few studies have focused on a possible direct causal association clinical presentation and is associated with progressive myocardial between ADHD symptoms and sleep-related problems, but only some dysfunction, thromboembolic events and dysrhythmia. of them have focused on nonclinical samples, namely preschoolers. Methods: Review of medical records of patients diagnosed with The aims of this study were to investigate the prevalence of high LVNC followed at a Pediatric Cardiology clinic. LVNC diagnosis was levels of ADHD symptoms in a nonclinical sample of children aged 3 performed through transthoracic echocardiography according to to 6 years old in Porto, characterize their sleep habits, and investigate Jenni criteria and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Demographic the association between ADHD symptoms and sleep. and clinical data, including family history, physical examination, Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted, by application electrocardiogram (ECG), 24-Holter monitoring, and genetic testing of a questionnaire to the caregivers of children attending a random were collected. -

Safety and Efficacy of Hysteroscopic Sterilization Compared BMJ: First Published As 10.1136/Bmj.H5162 on 13 October 2015

RESEARCH OPEN ACCESS Safety and efficacy of hysteroscopic sterilization compared BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.h5162 on 13 October 2015. Downloaded from with laparoscopic sterilization: an observational cohort study Jialin Mao,1 Samantha Pfeifer,2 Peter Schlegel,3 Art Sedrakyan1 1Department of Health Policy ABSTRACT higher risk of unintended pregnancy (odds ratio 0.84 and Research, Weill Medical OBJECTIVE (95% CI 0.63 to 1.12)) but was associated with a College of Cornell University, To compare the safety and efficacy of hysteroscopic substantially increased risk of reoperation (odds ratio New York, NY 10065, USA sterilization with the “Essure” device with laparoscopic 10.16 (7.47 to 13.81)) compared with laparoscopic 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Weill Medical sterilization in a large, all-inclusive, state cohort. sterilization. College of Cornell University, DESIGN CONCLUSIONS New York-Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY, USA Population based cohort study. Patients undergoing hysteroscopic sterilization have a 3Department of Urology, Weill SETTINGS similar risk of unintended pregnancy but a more than Medical College of Cornell Outpatient interventional setting in New York State. 10-fold higher risk of undergoing reoperation University, New York- compared with patients undergoing laparoscopic Presbyterian Hospital, PARTICIPANTS sterilization. Benefits and risks of both procedures New York, NY, USA Women undergoing interval sterilization procedure, should be discussed with patients for informed Correspondence to: including hysteroscopic sterilization with Essure A Sedrakyan decisions making. [email protected] device and laparoscopic surgery, between 2005 and 2013. Additional material is published Introduction online only. To view please visit MAIN OUTCOMES MEASURES Female sterilization is one of the most commonly used the journal online (http://dx.doi. -

Role of Laparoscopic Surgery in Infertility

Vol. 10, No. 2, 2005 Middle East Fertility Society Journal © Copyright Middle East Fertility Society REVIEW Role of laparoscopic surgery in infertility Bulent Berker, M.D.* Ali Mahdavi, M.D.† Babac Shahmohamady, M.D.‡ Camran Nezhat, M.D.§ Center for Special Minimally Invasive Surgery, Stanford University Medical Center, Palo Alto, California, USA Recent advances in endoscopic surgical Currently, laparoscopy is perceived as a minimally techniques and the increased sophistication of invasive surgical technique that both provides a surgical instruments have offered new operative panoramic & magnified view of the pelvic organs methods and techniques for the gynecologic and allows surgery at the time of diagnosis. surgeon (1). Recent years have witnessed a marked Laparoscopy has become an integral part of increase in the number of gynecological gynecologic surgery for the diagnosis and endoscopic procedures performed, mainly as a treatment of abdominal and pelvic disorders of the result of technological improvements in female reproductive organs. Endoscopic instrumentation. The addition of a small video reproductive surgery intended to improve fertility camera to the laparoscope (videolaparoscopy) may include surgery on the uterus, ovaries, pelvic greatly enhanced the popularity of operative peritoneum, and the Fallopian tubes. The aim of endoscopy because of the possibility of operating this review is to critically review the role of in a comfortable, upright position and using the laparoscopy in the management of infertility magnification capabilities of the camera (2,3). patients. *Bulent Berker, M.D., Post Doctoral Fellow, Center for Special Minimally Invasive Surgery, Stanford University ENDOSCOPIC TUBAL SURGERY Medical Center, Palo Alto, California 94304 † Ali Mahdavi, M.D., F.A.C.O.G. -

Surgical Prompt-Pay, Discounted Price Quotes

Surgical Prompt-Pay, Discounted Price Quotes All Physicians, Anesthesia, etc, bills separately unless otherwise noted. For two procedures, the second proc is 50% of the Cash Price. Procedure Notes Cash Price Abd Hysterectomy Inpatient up to 2 days 5,000 Abd Myomectomy Inpatient up to 3 days 4,000 Amputation Finger outpatient 2,500 Amputation foot Observation 3,500 Basic Metabolic Panel outpatient Lab 100 Biacuplasty outpatient 1,500 Bilateral Tubal Ligation outpatient 1,800 Blood Transfusion - 2 units of RBC outpatient 500 Blood Transfusion - 3 units of RBC outpatient 750 Bone Marrow Biopsy outpatient 1,500 Bone Marrow Aspiration Concentration outpatient 3,725 Bowel Repair/Colostomy Takedown Observation 3,000 Breast Biopsy, Unilateral outpatient 1,500 Bronchoscopy w/Biopsy outpatient 1,500 Carpal Tunnel Release outpatient 3,000 CBC/Diff outpatient Lab 35 Chalazion outpatient 2,000 Circumcision, adult outpatient 1,500 Circumcision, newborn outpatient/Post Discharge 150 Closed Reduc-wrist Observation 5,000 Closed trmt of nasal fracture outpatient 2,000 Colonoscopy outpatient 800 Comprehensive Metabolic Panel outpatient Lab 100 Correction of Bunion outpatient 2,000 CT Guided Lung Biopsy outpatient 1,500 D&C outpatient 1,500 Debridement outpatient surgery 2,000 Debridement Wound Care center 750 Diag Lap, Hysteroscopy, D&C outpatient 3,000 Drainage of Hydrocele outpatient 1,500 EGD outpatient 800 EGD & Colonoscopy outpatient 1,000 Enterocele Repair Observation 4,000 Epidural Steroid Inj (ESI) outpatient 1,200 Epidural/Subarchnoid Inj outpatient -

Definitive Contraception Marques Et Al

THIEME 344 Original Article Definitive Contraception: Trends in a Ten-year Interval Contracepção definitiva:tendênciasemumintervalode dez anos Cecília Maria Ventuzelo Marques1 Magda Maria do Vale Pinto Magalhães1 Maria João Leal da Silva Carvalho1,2 Giselda Marisa Costa Carvalho1 Francisco Augusto Falcão Santos Fonseca1 Isabel Torgal1,2 1 Gynecology A Service, Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra, Address for correspondence Cecília Maria Ventuzelo Marques, MD, Praceta Prof. Mota Pinto, Coimbra, Portugal Serviço de Ginecologia A, Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de 2 Department of Medicine, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Praceta Prof. Mota Pinto, 3000-075 Coimbra, Portugal Coimbra, Portugal (e-mail: [email protected]). Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2017;39:344–349. Abstract Objective To evaluate the trends in definitive contraception in a ten-year interval comprising the years 2002 and 2012. Method Retrospective analysis of the tubal sterilization performed in our service in 2002 and 2012, analyzing the demographic characteristics, personal history, previous contracep- tive method, definite contraception technique, effectiveness and complications. Results Definitive contraception was performed in 112 women in 2002 (group 1) and in 60 women in 2012 (group 2). The groups were homogeneous regarding age, parity, educational level and personal history. The number of women older than 40 years choosing a definitive method was more frequent in group 1, 49.1% (n ¼ 55); for group 2,theratewas34.8%(n ¼ 23) (p ¼ 0.04). The time between the last delivery and the procedure was 11.6 Æ 6.2 and 7.9 Æ 6.4 years (p ¼ 0.014) in 2002 against 2012 respectively. In 2002, all patients performed tubal ligation by laparoscopic inpatient regime.