LAPAROSCOPIC TUBAL ANASTOMOSIS Carlos Rotman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When to Consider Tubal Reversal Vs IVF Success Rates Point to Greater Outcomes with IVF for Women in Their Mid-Thirties and Older

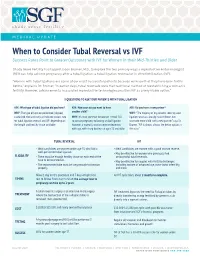

MEDICAL UPDATE When to Consider Tubal Reversal vs IVF Success Rates Point to Greater Outcomes with IVF for Women in their Mid-Thirties and Older Shady Grove Fertility has tapped Jason Bromer, M.D., to explore the two primary ways a reproductive endocrinologist (REI) can help achieve pregnancy after a tubal ligation: a tubal ligation reversal or in vitro fertilization (IVF). "Women with tubal ligations are some of our most successful patients because we know that they have been fertile before," explains Dr. Bromer. "In earlier days, tubal reversals were the traditional method of reestablishing a woman’s fertility. However, advancements in assisted reproductive technologies position IVF as a very viable option." 3 QUESTIONS TO ASK YOUR PATIENTS WITH TUBAL LIGATION ASK: What type of tubal ligation did you have? ASK: How soon do you want to have ASK: Do you have a new partner? WHY: The type of ligation performed (clipped, another child? WHY: "The majority of my patients seeking tubal cauterized, tied and cut) can indicate success rate WHY: It’s most common for women in their 30s ligation reversals already have children, but for tubal ligation reversal and IVF, depending on to pursue pregnancy following a tubal ligation. want one more child with a new partner," says Dr. the length and healthy tissue available. However, a woman’s ovarian reserve decreases Bromer. "IVF is almost always the better option in with age, with sharp declines at ages 35 and older. this case." TUBAL REVERSAL IVF • Ideal candidates are women under age 35 who had a • Ideal candidates are women with a good ovarian reserve. -

Successful Pregnancies After Removal of Intratubal Microinserts

2. Tonni G, De Felice C, Centini G, Ginanneschi C. Cervical and 5. Levine AB, Alvarez M, Wedgwood J, Berkowitz RL, Holzman oral teratoma in the fetus: a systematic review of etiology, I. Contemporary management of a potentially lethal fetal pathology, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Arch Gynecol anomaly: a successful perinatal approach to epignathus. Obstet Obstet 2010;282:355–61. Gynecol 1990;76:962–6. 3. Calda P, Novotna M, Cutka D, Brestak M, Haslik L, Goldova 6. Berrington JE, Stafford FW, Macphail S. Emergency EXIT for B, et al. A case of an epignathus with intracranial extension preterm labour after FETO. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed appearing as a persistently open mouth at 16 weeks and 2010;95:F376–7. subsequently diagnosed at 20 weeks of gestation. J Clin Ultra- 7. Hedrick HL, Flake AW, Crombleholme TM, Howell LJ, sound 2011;39:164–8. Johnson MP, Wilson RD, et al. The ex utero intrapartum 4. Marwan A, Crombleholme TM. The EXIT procedure: principles, therapy procedure for high-risk fetal lung lesions. J Pediatr pitfalls, and progress. Semin Pediatr Surg 2006;15:107–15. Surg 2005;40:1038–44. Successful Pregnancies After and who would like to conceive have two options: in vitro fertilization and sterilization reversal. Successful Removal of Intratubal Microinserts pregnancies resulting from in vitro fertilization after intratubal microinsert sterilization have been described.2 Charles W. Monteith, MD, Based on a literature search of the entire PubMed and Gary S. Berger, MD, MPH database up to August 2011 (using the key words “Essure” and “pregnancy”), these are the first two re- BACKGROUND: Patients with intratubal microinsert ports of successful pregnancy after surgical outpatient sterilization later may request reversal. -

Monash Health Referral Guidelines – Gynaecology

Monash Health Referral Guidelines (Incorporating Statewide Referral Criteria) GYNAECOLOGY EXCLUSIONS Services not offered In Vitro Fertilisation by Monash Health CONDITIONS CONTRACEPTIVE COUNSELLING MENSTRUAL MANAGEMENT Contraception Persistent, heavy menstrual bleeding Pregnancy Choices Bartholin's cysts / vaginal lesions Post-Menopausal bleeding Post-Coital bleeding DYSPLASIA Persistent or unexplained intermenstrual Dysplasia/Abnormal Cervical bleeding Screening Test Fibroids Vulval ulcers Vulval disorders PELVIC FLOOR/UROGYNAECOLOGY Genital warts Pelvic organ prolapse Urinary incontinence Recurrent UTI’s GYNAECOLOGY ENDOSCOPY Ovarian and other adnexal pathology Dyspareunia REPRODUCTIVE MEDICINE Pelvic Inflammatory disease Infertility Persistent pelvic pain Amenorrhea Male infertility Recurrent miscarriages GYNAECOLOGY ONCOLOGY Tubal & vasectomy reversal Cancer of the cervix Endocrine problems (Polycystic Ovarian cancer Ovarian Syndrome) Gynae cancers -suspected and confirmed SEXUAL MEDICINE & THERAPY CLINIC Sexual & relationship counselling MENOPAUSE Turner 's Syndrome Cancer and menopause PAEDIATRIC & ADOLESCENT GYNAE Premature menopause Paediatric and Adolescent Gynaecology General menopause ENDOMETRIOSIS Endometriosis Head of unit: Program Director: Last updated: Professor Beverley Vollenhoven Associate Professor Ryan Hodges 06/02/2020 Monash Health Referral Guidelines (Incorporating Statewide Referral Criteria) GYNAECOLOGY PRIORITY For emergency cases please do any of the following: EMERGENCY - send the patient to the Emergency -

Controversies and Complications in Pelvic Reconstructive Surgery (Didactic)

Controversies and Complications in Pelvic Reconstructive Surgery (Didactic) PROGRAM CHAIR Andrew I. Sokol, MD Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD Charles R. Rardin, MD Sponsored by AAGL Advancing Minimally Invasive Gynecology Worldwide Professional Education Information Target Audience Educational activities are developed to meet the needs of surgical gynecologists in practice and in training, as well as, other allied healthcare professionals in the field of gynecology. Accreditation AAGL is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians. The AAGL designates this live activity for a maximum of 3.75 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. DISCLOSURE OF RELEVANT FINANCIAL RELATIONSHIPS As a provider accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, AAGL must ensure balance, independence, and objectivity in all CME activities to promote improvements in health care and not proprietary interests of a commercial interest. The provider controls all decisions related to identification of CME needs, determination of educational objectives, selection and presentation of content, selection of all persons and organizations that will be in a position to control the content, selection of educational methods, and evaluation of the activity. Course chairs, planning committee members, presenters, authors, moderators, panel members, and others in a position to control the content of this activity are required to disclose relevant financial relationships with commercial interests related to the subject matter of this educational activity. Learners are able to assess the potential for commercial bias in information when complete disclosure, resolution of conflicts of interest, and acknowledgment of commercial support are provided prior to the activity. -

Gender Reassignment Surgery Policy Number: PG0311 ADVANTAGE | ELITE | HMO Last Review: 07/01/2021

Gender Reassignment Surgery Policy Number: PG0311 ADVANTAGE | ELITE | HMO Last Review: 07/01/2021 INDIVIDUAL MARKETPLACE | PROMEDICA MEDICARE PLAN | PPO GUIDELINES This policy does not certify benefits or authorization of benefits, which is designated by each individual policyholder terms, conditions, exclusions and limitations contract. It does not constitute a contract or guarantee regarding coverage or reimbursement/payment. Self-Insured group specific policy will supersede this general policy when group supplementary plan document or individual plan decision directs otherwise. Paramount applies coding edits to all medical claims through coding logic software to evaluate the accuracy and adherence to accepted national standards. This medical policy is solely for guiding medical necessity and explaining correct procedure reporting used to assist in making coverage decisions and administering benefits. SCOPE X Professional X Facility DESCRIPTION Transgender is a broad term that can be used to describe people whose gender identity is different from the gender they were thought to be when they were born. Gender dysphoria (GD) or gender identity disorder is defined as evidence of a strong and persistent cross-gender identification, which is the desire to be, or the insistence that one is of the other gender. Persons with this disorder experience a sense of discomfort and inappropriateness regarding their anatomic or genetic sexual characteristics. Individuals with GD have persistent feelings of gender discomfort and inappropriateness of their anatomical sex, strong and ongoing cross-gender identification, and a desire to live and be accepted as a member of the opposite sex. Gender Dysphoria (GD) is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Fifth Edition, DSM-5™ as a condition characterized by the "distress that may accompany the incongruence between one’s experienced or expressed gender and one’s assigned gender" also known as “natal gender”, which is the individual’s sex determined at birth. -

Oophorectomy Or Salpingectomy— Which Makes More Sense?

Oophorectomy or salpingectomy— which makes more sense? During hysterectomy for benign indications, many surgeons routinely remove the ovaries to prevent cancer. Here’s what we know about this practice. William H. Parker, MD CASE Patient opts for hysterectomy, asks than age 45 to prevent the subsequent devel- about oophorectomy opment of ovarian cancer (FIGURES 1 and 2). Your 46-year-old patient reports increasingly The 2002 Women’s Health Initiative re- severe dysmenorrhea at her annual visit, and a port suggested that exogenous hormone use pelvic examination reveals an enlarged uterus. was associated with a slight increase in the You order pelvic magnetic resonance imaging, risk of breast cancer.2 After its publication, which shows extensive adenomyosis. the rate of oophorectomy at the time of hys- After you counsel the patient about terectomy declined slightly, likely reflect- IN THIS her options, she elects to undergo lapa- ARTICLE ing women’s desire to preserve their own roscopic supracervical hysterectomy and source of estrogen.3 For women younger Algorithm: Should asks whether she should have her ovaries than age 50, further slight declines in the rate the ovaries removed at the time of surgery. She has no of oophorectomy were seen from 2002 to be removed? family history of ovarian or breast cancer. 2010. However, in the United States, almost page 54 What would you recommend for this 300,000 women still undergo “prophylactic” woman, based on her situation and current bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy every year.4 medical research? The lifetime risk of ovarian cancer Ovarian cancer does among women with a BRCA 1 mutation not come from the prophylactic procedure should be is 36% to 46%, and it is 10% to 27% among ovary considered only if 1) there is a rea- women with a BRCA 2 mutation. -

Salpingectomy for Ovarian Cancer Prevention Approved 11/9/2017

Health Evidence Review Commission (HERC) Coverage Guidance: Opportunistic Salpingectomy for Ovarian Cancer Prevention Approved 11/9/2017 HERC Coverage Guidance Opportunistic salpingectomy during gynecological procedures is recommended for coverage, without an increased payment (i.e., using a form of reference-based pricing) (weak recommendation). Note: Definitions for strength of recommendation are in Appendix A. GRADE Informed Framework Element Description. Table of Contents HERC Coverage Guidance ............................................................................................................................. 1 Rationale for development of coverage guidances and multisector intervention reports .......................... 3 GRADE-Informed Framework ....................................................................................................................... 4 Should opportunistic salpingectomy be recommended for coverage for ovarian cancer risk reduction? .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Clinical Background ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Indications ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Technology Description ........................................................................................................................... -

A Personal Choice with Dr. Monteith Where Permanent

A Personal Choice With Dr. Monteith Where Permanent THE MAGAZINE Is Not Forever FOR HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS A Personal Choice with Dr. Monteith Specializing in Male and Female Sterilization Reversal and No-Needle No-Scalpel Vasectomy Women and men travel across the United Many within the medical community re- The new practice name is a reflection of States and around the world to A Personal call the practice when it was Chapel Hill the broader vision, says Dr. Monteith. “Our Choice of Raleigh, a unique practice dedi- Tubal Reversal Center, founded by Gary S. new name may not be understandable to cated to outpatient, minimally invasive Berger, M.D. Dr. Monteith joined Dr. Berger the general public but for those who seek sterilization and sterilization reversal ser- there in 2008, and together they provided our services the immense meaning of our vices in a state-of-the-art facility. a unique form of tubal ligation reversal name is readily apparent,” he says. that allows faster patient recovery, avoids The surgical specialty practice exclusively prolonged hospitalization and decreases A Personal Choice is conveniently located offers tubal ligation reversal, and vasec- patient recovery time. near North Hills Mall and Midtown Raleigh, tomy and vasectomy reversal. Tubal rever- so patients can stay in one of the nearby sal and vasectomy reversal have proven to After Dr. Berger retired in 2013, Dr. Monte- luxury hotels and walk to many restaurants be more effective and are more affordable ith expanded on his health care vision by and entertainment venues. The area also than alternative treatments, and vasectomy giving male patients greater reproductive provides closer access to Raleigh Durham is safer than tubal ligation. -

(8Th Edition) Procedure Code ACHI (8

Appendix 1. Procedure and Diagnostic Codes Used to Identify Prior Procedures Procedure ACHI (8th ACHI (8th edition) procedure names ICD-10- ICD-10-AM edition) AM diagnosis name procedure diagnosis code code Gynecological laparoscopy 35638-00 Laparoscopic wedge resection of ovary 35638-01 Laparoscopic partial oophorectomy 35638-02 Laparoscopic oophorectomy, unilateral 35638-03 Laparoscopic oophorectomy,bilateral 35638-04 Laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy, unilateral 35638-05 Laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy, bilateral 35638-06 Laparoscopic salpingotomy 35638-07 Laparoscopic partial salpingectomy, unilateral 35638-08 Laparoscopic partial salpingectomy, bilateral 35638-09 Laparoscopic salpingectomy, unilateral 35638-10 Laparoscopic salpingectomy, bilateral 35638-11 Laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy, unilateral 35638-12 Laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy, bilateral 35638-14 Laparoscopic uterosacral nerve ablation 35637-02 Laparoscopic diathermy of lesion of pelvic cavity 35637-04 Laparoscopic ventrosuspension 35637-07 Laparoscopic rupture of ovarian cyst or abscess 35637-08 Laparoscopic ovarian drilling 35637-10 Laparoscopic excision of lesion of pelvic cavity 35729-00 Laparoscopic transposition of ovary 90430-00 Laparoscopic repair of ovary 90433-00 Other laparoscopic repair of fallopian tube 35694-00 Laparoscopic salpingoplasty 35694-01 Laparoscopic anastomosis of fallopian tube 35694-02 Laparoscopic salpingolysis 35694-03 Laparoscopic salpingostomy 35694-06 Laparoscopic salpingotomy 35649-01* Myomectomy of uterus via laparoscopy Hysteroscopy, including operative hysteroscopy 35630-00 Diagnostic hysteroscopy 35649-00 Hysterotomy 35633-00 Division of uterine adhesions 35634-00 Division of uterine septum via hysteroscopy 35649-02 Division of uterine septum via hysterotomy 35633-01 Polypectomy of uterus via hysteroscopy 35623-00 Myomectomy of uterus via hysteroscopy Baldwin HJ, Patterson JA, Nippita TA, Torvaldsen S, Ibiebele I, Simpson JM, et al. Antecedents of abnormally invasive placenta in primiparous women: the risk from gynecologic procedures. -

Sex Reassignment Surgery Page 1 of 14

Sex Reassignment Surgery Page 1 of 14 Medical Policy An Independent licensee of the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association Title: Sex Reassignment Surgery PRE-DETERMINATION of services is not required, but is highly recommended. http://www.bcbsks.com/CustomerService/Forms/pdf/15-17_predeterm_request_frm.pdf Professional Institutional Original Effective Date: January 1, 2017 Original Effective Date: January 1, 2017 Revision Date(s): January 1, 2017; Revision Date(s): January 1, 2017; January 27, 2021; March 18, 2021 January 27, 2021; March 18, 2021 Current Effective Date: January 1, 2017 Current Effective Date: January 1, 2017 State and Federal mandates and health plan member contract language, including specific provisions/exclusions, take precedence over Medical Policy and must be considered first in determining eligibility for coverage. To verify a member's benefits, contact Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas Customer Service. The BCBSKS Medical Policies contained herein are for informational purposes and apply only to members who have health insurance through BCBSKS or who are covered by a self-insured group plan administered by BCBSKS. Medical Policy for FEP members is subject to FEP medical policy which may differ from BCBSKS Medical Policy. The medical policies do not constitute medical advice or medical care. Treating health care providers are independent contractors and are neither employees nor agents of Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas and are solely responsible for diagnosis, treatment and medical advice. If your patient is covered under a different Blue Cross and Blue Shield plan, please refer to the Medical Policies of that plan. DESCRIPTION Gender dysphoria involves a conflict between a person's physical or assigned gender and the gender with which he/she/they identify. -

Post Sterilization Tuboplasty: Boon Or Bain !

Indian Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Case Report 107 Volume 5 Number 1, January - March 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21088/ijog.2321.1636.5117.19 Post Sterilization Tuboplasty: Boon or Bain ! Mukti S. Harne*, Sumedha Harne**, Urmila Gavali*** Abstract fertilization for the next pregnancy, leading to compulsion on women to undergo tubal reversal. The incidence of a successful India is developing country, yet pregnancy after tubal ligation is 40%. There the development is less in the are many predisposing factors for the success medical sector. Though the of the pregnancy like the tubal length after awareness of tubal ligation is vividly surgery should be >4 cm, absence of present in the rural set up, pressure hydrosalpingnx and previous birth within on females are increasing due to 5 years [1]. preference of male child in the society. Some unfortunate We, at our institution encountered, an circumstances, may it be pressure unfortunate case of a couple, with history of from the family members or secondary infertility and belonging to the unfortunate death of the existing muslim community, who were anxious to children or poor economic status of conceive since 3 years and weren’t the family to afford the In vitro investigated previously. This 24 years, fertilization for the next pregnancy, Shabana Shaikh, P1D1, housewife by leading to compulsion on women to occupation and resident of Ahmednagar, undergo tubal reversal. Hence, this came with her husband in the gynaec opd. case was brought to notice,while Detailed history of the couple was taken . emphasis was laid on the surgical Her menstrual history was regular, management of a case that we monthly interval, soaking 1-2 pads per day, managed. -

The Costs and Benefits of Moving to the ICD-10 Code Sets

CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CIVIL JUSTICE service of the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE 6 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS POPULATION AND AGING The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY organization providing objective analysis and effective SUBSTANCE ABUSE solutions that address the challenges facing the public TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY and private sectors around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Science and Technology View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. This product is part of the RAND Corporation technical report series. Reports may include research findings on a specific topic that is limited in scope; present discus- sions of the methodology employed in research; provide literature reviews, survey instruments, modeling exercises, guidelines for practitioners and research profes- sionals, and supporting documentation;