NEETZ-THESIS-2021.Pdf (1.461Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quarterly Report to Members, Subscribers and Friends

Quarterly Report to Members, Subscribers and Friends Third Quarter, 2014 Q3 highlights: effective and efficient policy research & outreach Q3 research 11 research papers 2 Monetary Policy Council releases Q3 policy events 10 policy events and special meetings, including: Calgary Roundtable – The Hon. Doug Horner, President of Treasury Board & Minister of Finance, Government of Alberta Toronto Luncheon Event - 2014 Toronto Mayoral Candidates Policy Outreach in Q3 38,898 website pageviews in Q3 2014 7 policy outreach presentations 37 National Post and Globe and Mail citations Citations in more than 70 media outlets 34 media interviews 17 opinion and editorial pieces 2 Q3 select policy influence The Independent Electricity System Operator invites stakeholders to provide input into the design for a capacity auction The Institute has long argued that Ontario electricity consumers would enjoy less risk and lower prices if the province moved to a capacity market for obtaining generation. Reports: “Rethinking Ontario’s Electricity System with Consumers in Mind” and “A New Blueprint for Ontario’s Electricity Market” Institute op-eds: “How to free Ontario’s electricity market” (Financial Post) The Institute was pleased to host an off-the-record policy roundtable luncheon examining the prospect of an electricity capacity market in Ontario. This panel event, entitled “What’s Next for Ontario’s Electricity Market?”, featured experts Terry Boston of PJM Interconnection, A.J. Goulding of London Economics International LLC, and Bryne Purchase of Queen’s University. 3 Q3 publications 1. Target-Benefit Plans in Canada – An Innovation Worth Exploring - July 9, 2014 – Angela Mazerolle, Jana Steele, Mel Bartlett 2. Capital Needed: Canada Needs More Robust Business Investment - July 17, 2014 – Benjamin Dachis, William B.P. -

National Newspaper Awards Concours Canadien De Journalisme

NATIONAL NEWSPAPER AWARDS CONCOURS CANADIEN DE JOURNALISME FINALISTS/FINALISTES - 2012 Multimedia Feature/Reportage multimédia Investigations/Grande enquête La Presse, Montréal The Canadian Press Steve Buist, Hamilton Spectator The Globe and Mail Isabelle Hachey, La Presse, Montréal Winnipeg Free Press Huffington Post team David Bruser, Jesse McLean, Toronto Star News Feature Photography/Photographie de reportage d’actualité Arts and Entertainment/Culture Tyler Anderson, National Post Aaron Elkaim, The Canadian Press J. Kelly Nestruck, The Globe and Mail Lyle Stafford, Victoria Times-Colonist Stephanie Nolen, The Globe and Mail Sylvie St-Jacques, La Presse, Montreal Beats/Journalisme spécialisé Sports/Sport Jim Bronskill, The Canadian Press Sharon Kirkey, Postmedia News David A. Ebner, The Globe and Mail Heather Scoffield, The Canadian Press Dave Feschuk, Toronto Star Mary Agnes Welch, Winnipeg Free Press Roy MacGregor, The Globe and Mail Explanatory work/Texte explicatif Feature Photography/Photographie de reportage James Bagnall, Ottawa Citizen Tyler Anderson, National Post Ian Brown, The Globe and Mail Peter Power, The Globe and Mail Mary Ormsby, Toronto Star Tim Smith, Brandon Sun Politics/Politique International /Reportage à caractère international Linda Gyulai, The Gazette, Montreal Agnès Gruda, La Presse, Montréal Stephen Maher, Glen McGregor, Postmedia News/The Ottawa Michèle Ouimet, La Presse, Montréal Citizen Geoffrey York, The Globe and Mail Peter O’Neil, The Vancouver Sun Editorials/Éditorial Short Features/Reportage bref David Evans, Edmonton Journal Erin Anderssen, The Globe and Mail Jordan Himelfarb, Toronto Star Jayme Poisson, Toronto Star John Roe, Waterloo Region Record Lindor Reynolds, Winnipeg Free Press Editorial Cartooning/Caricature Local Reporting/Reportage à caractère local Serge Chapleau, La Presse, Montréal Cam Fortems, Michele Young, Kamloops Daily News Andy Donato, Toronto Sun Susan Gamble, Brantford Expositor Brian Gable, The Globe and Mail Barb Sweet, St. -

Cotwsupplemental Appendix Fin

1 Supplemental Appendix TABLE A1. IRAQ WAR SURVEY QUESTIONS AND PARTICIPATING COUNTRIES Date Sponsor Question Countries Included 4/02 Pew “Would you favor or oppose the US and its France, Germany, Italy, United allies taking military action in Iraq to end Kingdom, USA Saddam Hussein’s rule as part of the war on terrorism?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 8-9/02 Gallup “Would you favor or oppose sending Canada, Great Britain, Italy, Spain, American ground troops (the United States USA sending ground troops) to the Persian Gulf in an attempt to remove Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 9/02 Dagsavisen “The USA is threatening to launch a military Norway attack on Iraq. Do you consider it appropriate of the USA to attack [WITHOUT/WITH] the approval of the UN?” (Figures represent average across the two versions of the UN approval question wording responding “under no circumstances”) 1/03 Gallup “Are you in favor of military action against Albania, Argentina, Australia, Iraq: under no circumstances; only if Bolivia, Bosnia, Bulgaria, sanctioned by the United Nations; Cameroon, Canada, Columbia, unilaterally by America and its allies?” Denmark, Ecuador, Estonia, (Figures represent percent responding “under Finland, France, Georgia, no circumstances”) Germany, Iceland, India, Ireland, Kenya, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Malaysia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Pakistan, Portugal, Romania, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Uganda, United Kingdom, USA, Uruguay 1/03 CVVM “Would you support a war against Iraq?” Czech Republic (Figures represent percent responding “no”) 1/03 Gallup “Would you personally agree with or oppose Hungary a US military attack on Iraq without UN approval?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 2 1/03 EOS-Gallup “For each of the following propositions tell Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, me if you agree or not. -

The President Announced That the Sarwon Shaota Award

RYERSON UNIVERSITY SENATE MEETING AGENDA Tuesday, March 6, 2007 ______________________________________________________________________________ 5:30 p.m. Dinner will be served in The Commons, Jorgenson Hall, Room POD-250. 6:00 p.m. Meeting in The Commons. ______________________________________________________________________________ 1. President's Report Pages 1-4 1.1 President’s Update Pages 5-9 1.2 Ryerson Achievement Report 1.3 Results of the 2006 Graduating Student Survey – Paul Stenton 2. Report of the Secretary of Academic Council – W2007-1 Pages 10-11 2.1 Academic Council Election Results 3. The Good of the University 4. Minutes: Pages 12-18 4.1 Minutes of the January 30, 2007 Meeting 5. Business Arising from the Minutes 6. Correspondence 7. Reports of Actions and Recommendations of Departmental and Divisional Councils Page 19 7.1 From Community Services: Course changes from Urban & Regional Planning Pages 20-22 7.2 From Engineering, Architecture and Science: Course changes in First-Year and Common Engineering; and Mathematics 8. Reports of Committees Pages 23-26 8.1 Report #W2007-2 of the Composition and By-Laws Committee 8.1.1 Motion : That Academic Council approve the School By-laws submitted by the School of Journalism Page 27 8.2 Report #W2007-2 of the Nominating Committee: 8.2.1 Motion: That Academic Council approve the nominees for the Standing Committees as listed in the report. 9. New Business Page 28 9.1 Amendments to Policy 157 9.1.1 Motion: That Academic Council approve the amendments to policy 157. 10. Adjournment Ryerson University Academic Council President’s Update February 20, 2007 Application Statistics Fall 2007 – First choice applications for Ryerson continue to position the university at the forefront of demand. -

The Impact of ABC Canada's LEARN Campaign. Results of a National Research Study

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 472 CE 073 669 AUTHOR Long, Ellen TITLE The Impact of ABC Canada's LEARN Campaign. Results of a National Research Study. INSTITUTION ABC Canada, Toronto (Ontario). SPONS AGENCY National Literacy Secretariat, Ottawa (Ontario). PUB DATE Jul 96 NOTE 99p. PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; *Adult Literacy; Adult Programs; *Advertising; Foreign Countries; High School Equivalency Programs; *Literacy Education; Marketing; *Program Effectiveness; *Publicity IDENTIFIERS *Canada; *Literacy Campaigns ABSTRACT An impact study was conducted of ABC CANADA's LEARN campaign, a national media effort aimed at linking potential literacy learners with literacy groups. Two questionnaires were administered to 94 literacy groups, with 3,557 respondents. Findings included the following:(1) 70 percent of calls to literacy groups were from adult learners aged 16-44;(2) more calls were received from men in rural areas and from women in urban areas; (3) 77 percent of callers were native English speakers;(4) 80 percent of callers had not completed high school, compared with 38 percent of the general population; (5) about equal numbers of learners were seeking elementary-level literacy classes and high-school level classes;(6) 44 percent of all calls to literacy organizations were associated with the LEARN campaign; and (7) 95 percent of potential learners who saw a LEARN advertisement said it helped them decide to call. The study showed conclusively that the LEARN campaign is having a profound impact on potential literacy learners and on literacy groups in every part of Canada. (This report includes 5 tables and 24 figures; 9 appendixes include detailed information on the LEARN campaign, the participating organizations, the surveys, and the impacts on various groups.) (KC) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Ontario Energy

Appendix A – List of Publications English Dailies 33 Timmins Daily Press 1 Barrie Examiner 34 Toronto Star 2 Belleville Intelligencer 35 Welland-Port Colborne Tribune 3 Brantford Expositor 36 Windsor Star 4 Brockville Recorder 37 Woodstock Sentinel Review 5 Chatham Daily News 6 Cobourg Daily Star English Weeklies 7 Cornwall Standard Freeholder 1 Atikokan Progress 8 Fort Frances Daily Bulletin 2 Chapleau Express 9 Globe & Mail (Ontario Edition) 3 Cochrane Times-Post 10 Guelph Mercury 4 Dryden Observer 11 Hamilton Spectator 5 Fort Frances Times 12 Kenora Daily Miner 6 Geraldton Times Star 13 Kingston-Whig Standard 7 Hornepayne Jackfish Journal 14 Kitchener/Waterloo Record 8 Ignace Driftwood 15 Lindsay Daily Post 9 Iroquois Falls Enterprise 16 London Free Press 10 James Bay Voice 17 Niagara Falls Review 11 Kapuskasing Le/The Weekender 18 North Bay Nugget 12 Kenora Lake of the Woods Enterprise 19 Orillia Packet & Times 13 Manitouwadge Echo 20 Ottawa Citizen 14 Marathon Mercury 21 Ottawa Le Droit (FRENCH) 15 New Liskeard Temiskaming Speaker 22 Owen Sound Sun Times 16 Nipigon Superior Sentinel 23 Pembroke Observer 17 Rainy River West End Weekly 24 Peterborough Examiner 18 Red Lake Northern Sun News 25 Sarnia Observer 19 Sioux Lookout Bulletin 26 Sault Ste Marie Star 20 Terrace Bay/Schreiber News 27 Simcoe Reformer 21 Thunder Bay's Source 28 St. Catharines Standard 22 Timmins Times 29 St. Thomas Times Journal 23 Wawa Algoma News Review 30 Stratford Beacon Herald 24 Tekawennake (First Nation) 31 Sudbury Star 25 Turtle Island News (First Nation) -

Daily Newspapers / 147 Dailydaily Newspapersnewspapers

Media Names & Numbers Daily Newspapers / 147 DailyDaily NewspapersNewspapers L’Acadie Nouvelle E-Mail: [email protected] Dave Naylor, City Editor Circulation: 20000 Larke Turnbull, City Editor Phone: 403-250-4122/124 CP 5536, 476, boul. St-Pierre Ouest, Phone: 519-271-2220 x203 E-Mail: [email protected] Caraquet, NB E1W 1K0 E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: 506-727-4444 800-561-2255 Cape Breton Post FAX: 506-727-7620 The Brandon Sun Circulation: 28300 E-Mail: [email protected] Circulation: 14843, Frequency: Weekly P.O. Box 1500, 255 George St., WWW: www.acadienouvelle.com 501 Rosser Ave., Brandon, MB R7A 0K4 Sydney, NS B1P 6K6 Gaetan Chiasson, Directeur de l’information Phone: 204-727-2451 FAX: 204-725-0976 Phone: 902-564-5451 FAX: 902-564-6280 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] WWW: www.capebretonpost.com Bruno Godin, Rédacteur en Chef WWW: www.brandonsun.com E-Mail: [email protected] Craig Ellingson, City Editor Bonnie Boudreau, City Desk Editor Phone: 204-571-7430 Phone: 902-563-3839 FAX: 902-562-7077 Lorio Roy, Éditeur E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Jim Lewthwaite, News Editor Fred Jackson, Managing Editor Alaska Highway News Phone: 204-571-7433 Phone: 902-563-3843 Circulation: 3700 Gord Wright, Editor-in-Chief E-Mail: [email protected] 9916-98th St., Fort St. John, BC V1J 3T8 Phone: 204-571-7431 Chatham Daily News Phone: 250-785-5631 FAX: 250-785-3522 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Circulation: 15600 WWW: www.cna-acj.ca Brockville Recorder and Times P.O. -

A Free and Independent Press Has Become One of the Hallmarks of a Healthy Democracy

PROVINCIAL UNITY AMIDST A DIMINISHING PRESS GALLERY by LESLIE DE MEULLES 2009-2010 INTERN THE ONTARIO LEGISLATURE INTERNSHIP PROGRAMME (OLIP) 1303A WHITNEY BLOCK QUEEN'S PARK TORONTO, ONTARIO M7A 1A1 EMAIL: [email protected] PAPER PRESENTED AT THE 2010 ANNUAL MEETING OF THE CANADIAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION, MONTREAL,QUÉBEC, WEDNESDAY, JUNE 2nd, 2010. A free and independent press has become one of the hallmarks of a healthy democracy. Press galleries and bureaus have similarly become a cornerstone of the democratic process insofar as they independently report on, and keep politicians accountable. However, the Ontario Legislature Press Gallery membership has been declining over the past 20 years. This decline may very well be an indicator that this „valued‟ democratic institution is in dire straits. This paper attempts to explain why the Press Gallery is shrinking and how decreasing number have led to a lack of political coverage to Northern Ontario, and is leading Northern constituents to rely heavily on their MPPs as a source of political news. This is problematic, as MPP communication can hardly be expected to be non-partisan, objective reporting on the events at Queen‟s Park. That people in Northern Ontario rely on partisan political messaging as a substitute for political news shows how the media as an institution is failing the North, as relying on these forms of communication is akin to relying on propaganda. Due to a dearth of literature on the Ontario Legislature, the research for this paper relied on interviews conducted with Northern MPPs, and current and former Press Gallery members1. The paper exists in three parts. -

Media Tree Letter

CANADIAN MEDIA LANDSCAPE 2006 TELEVISION SPECIALTY TV CHANNELS Showcase History Television Life Network HGTV Canada (80.2%) Food Network Canada (57.58%) Fine Living Showcase Action Showcase Diva +10 others full or part ownership TOTAL BROADCAST REVENUES: $283.4 MILLION CANADIAN MEDIA LANDSCAPE 2006 TELEVISION RADIO INTERNET OUT OF HOME SPECIALTY TV CHANNELS CFXY the Fox, Fredericton, N.B. Radiolibre.ca 3,700 faces Canal Vie CKTY 99.5 Truro, N.S. Teatv.ca (online classified) in Ontario and Quebec MusiMax Energie 94.3, Montreal, QC Historia +26 others Cinepop +7 others full or part ownership PAY TV CHANNELS TOTAL REVENUES: $549.6 MILLION The Movie Network Viewer's Choice TV: $391.1 MILLION Super Ecran Radio: $110.4 MILLION Outdoor: +3 others $42.2 MILLION Web not broken out separately CANADIAN MEDIA LANDSCAPE 2006 TELEVISION NEWSPAPERS MAGAZINES INTERNET NETWORK TV The Globe and Mail Report on Business globeandmail.com CTV Globe Television robtv.com ASN ctv.ca TQS (40% ownership) tsn.ca REVENUE FIGURES: N/A mtv.ca SPECIALTY TV CHANNELS workopolis.com (40%) ROB TV +15 others MTV (launched CTV Broadband Dec. 2, 2005: The Comedy Network BGM parent company BCE Inc. reduces its network this summer) TSN (70 %) ownership stake in BCE to 20% from 48.5%. Torstar Discovery Channel (56%) and the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan each pay $283 million for a 20% stake in the company, while the Thomson NHL Network (15%) family’s Woodbridge Inc. pays $120 million to increase its ownership +11 others full or partial stake to 40% from 31.5%. On Sept. -

Media Ownership and News Coverage of International Conflict

Media Ownership and News Coverage of International Conflict Matthew Baum Yuri Zhukov Harvard Kennedy School University of Michigan matthew [email protected] [email protected] How do differences in ownership of media enterprises shape news coverage of international conflict? We examine this relationship using a new dataset of 591,532 articles on US-led multinational military opera- tions in Libya, Iraq, Afghanistan and Kosovo, published by 2,505 newspapers in 116 countries. We find that ownership chains exert a homogenizing effect on the content of newspapers’ coverage of foreign pol- icy, resulting in coverage across co-owned papers that is more similar in scope (what they cover), focus (how much “hard” relative to “soft” news they offer), and diversity (the breadth of topics they include in their coverage of a given issue) relative to coverage across papers that are not co-owned. However, we also find that competitive market pressures can mitigate these homogenizing effects, and incentivize co-owned outlets to differentiate their coverage. Restrictions on press freedom have the opposite impact, increasing the similarity of coverage within ownership chains. February 27, 2018 What determines the information the press reports about war? This question has long concerned polit- ical communication scholars (Hallin 1989, Entman 2004). Yet it is equally important to our understanding of international conflict. Prevailing international relations theories that take domestic politics into account (e.g., Fearon 1994, 1995, Lake and Rothschild 1996, Schultz 2001) rest on the proposition that the efficient flow of information – between political leaders and their domestic audiences, as well as between states involved in disputes – can mitigate the prevalence of war, either by raising the expected domestic political costs of war or by reducing the likelihood of information failure.1 Yet models of domestic politics have long challenged the possibility of a perfectly informed world (Downs 1957: 213). -

Get Maximum Exposure to the Largest Number of Professionals in The

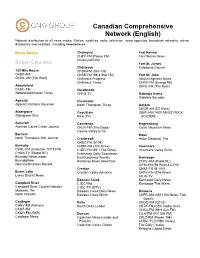

Canadian Comprehensive Network (English) National distribution to all news media. Dailies, weeklies, radio, television, news agencies, broadcast networks, online databases and websites, including newswire.ca. News Media Chetwynd Fort Nelson CHET-FM [Peace FM] Fort Nelson News Chetwynd Echo British Columbia Fort St. James Chilliwack Caledonia Courier 100 Mile House CFSR-FM (Star FM) CKBX-AM CKSR-FM (98.3 Star FM) Fort St. John CKWL-AM [The Wolf] Chilliwack Progress Alaska Highway News Chilliwack Times CHRX-FM (Energy 98) Abbotsford CKNL-FM (The Bear) CKQC-FM Clearbrook Abbotsford/Mission Times CFEG-TV Gabriola Island Gabriola Sounder Agassiz Clearwater Agassiz Harrison Observer North Thompson Times Golden CKGR-AM [EZ Rock] Aldergrove Coquitlam CKIR-AM [1400 AM EZ ROCK Aldergrove Star Now, The GOLDEN] Ashcroft Courtenay Hagensborg Ashcroft Cache Creek Journal CKLR-FM (The Eagle) Coast Mountain News Comox Valley Echo Barriere Hope North Thompson Star Journal Cranbrook Hope Standard, The CHBZ-FM (B104) Burnaby CHDR-FM (The Drive) Invermere CFML-FM (Evolution 107.9 FM) CJDR-FM (99.1 The Drive) Invermere Valley Echo CHAN-TV (Global BC) Cranbrook Daily Townsman Burnaby NewsLeader East Kootenay Weekly Kamloops BurnabyNow Kootenay News Advertiser CHNL-AM (Radio NL) New Westminster Record CIFM-FM (98 Point 3 CIFM) Creston CKBZ-FM (B-100) Burns Lake Creston Valley Advance CKRV-FM (The River) Lakes District News CFJC-TV Dawson Creek Kamloops Daily News Campbell River CJDC-AM Kamloops This Week Campbell River Courier-Islander CJDC-TV (NTV) Midweek, -

Quarterly Report to Members, Subscribers and Friends

Quarterly Report to Members, Subscribers and Friends Third Quarter, 2013 Q3 highlights: effective and efficient policy research & outreach Q3 research 12 research papers 2 Monetary Policy Council releases Q3 policy events 1 policy conference, 4 policy roundtables Policy Outreach in Q3 86,700 website pageviews in Q3 2013, up from 72,200 pageviews in Q3 2012 9 policy outreach presentations 50 National Post and Globe and Mail citations Citations in 67 media outlets 47 media interviews 14 opinion and editorial pieces New member benefit The Institute’s event space is now available to members 2 Q3 select policy impact Alberta proposed significant changes to public sector pensions, including an end to early retirement incentives Work by the Institute has recommended significant changes to federal and provincial public sector pension plans Examples include “Ontario Pension Policy 2013: Key Challenges Ahead,” “The Pension Crisis Deepens,” “Ottawa’s Pension Abyss: The Rapid Hidden Growth of Federal-Employee Retirement Liabilities,” and “Alberta’s pension evolution is a step in the right direction,” The Competition Tribunal addressed governance, structural and funding constraints affecting the ability of Interac to compete effectively and meet market demands The Institute’s 2012 paper “Debit, Credit and Cell: Making Canada a Leader in the Way We Pay,” argued that Canada’s current payment technologies and governance infrastructure must change, or we would fall further behind the rest of the world. This change was also recommended in a 2011 Financial Post op-ed, “Set Interac Free.” Ontario adopted transportation planning methodology from a C.D. Howe report The Institute released “Cars, Congestion and Costs: A New Approach to Evaluating Government Infrastructure Investment” in July 2013.