Steroids, Home Runs and the Law of Genius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major League Baseball in Nineteenth–Century St. Louis

Before They Were Cardinals: Major League Baseball in Nineteenth–Century St. Louis Jon David Cash University of Missouri Press Before They Were Cardinals SportsandAmerican CultureSeries BruceClayton,Editor Before They Were Cardinals Major League Baseball in Nineteenth-Century St. Louis Jon David Cash University of Missouri Press Columbia and London Copyright © 2002 by The Curators of the University of Missouri University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201 Printed and bound in the United States of America All rights reserved 54321 0605040302 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cash, Jon David. Before they were cardinals : major league baseball in nineteenth-century St. Louis. p. cm.—(Sports and American culture series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8262-1401-0 (alk. paper) 1. Baseball—Missouri—Saint Louis—History—19th century. I. Title: Major league baseball in nineteenth-century St. Louis. II. Title. III. Series. GV863.M82 S253 2002 796.357'09778'669034—dc21 2002024568 ⅜ϱ ™ This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984. Designer: Jennifer Cropp Typesetter: Bookcomp, Inc. Printer and binder: Thomson-Shore, Inc. Typeface: Adobe Caslon This book is dedicated to my family and friends who helped to make it a reality This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix Prologue: Fall Festival xi Introduction: Take Me Out to the Nineteenth-Century Ball Game 1 Part I The Rise and Fall of Major League Baseball in St. Louis, 1875–1877 1. St. Louis versus Chicago 9 2. “Champions of the West” 26 3. The Collapse of the Original Brown Stockings 38 Part II The Resurrection of Major League Baseball in St. -

Mobile Baseball, 1868-1910

Transcribed Pages from the Charles Dickson Papers on Mobile Baseball Box 3 Folder 1: Mobile Baseball 1868-1910 1. Early Base Ball in Mobile The first record of baseball games being played in Mobile was an account in the Mobile Daily News, Feb. 1st 1868 – The game was for the championship of the state between the: -- Dra [illegible] and the Mobile ball club resulting in a score of 63 to 50 in favor of the Dra[illegible]. It took 2 hours and fourty minutes time to play the game, which was said to be very exciting to five hundred who witnessed the game, not withstanding the very cold weather on that February afternoon. There is no mention of the number of innings that were played,(if any) before the contest was ended. From the report of the game, it is evident that each player of the nine on each team were individually credited by the scores that they made and charged with the number of times that they were Tagged out. R. Ellison was the umpire and R. Goubil and W. Madderu were score keepers. -- Champion Base Ball Match – Dra[illegible] Mobile Player Position Outs Runs Player Position Outs Runs Allen P 2 9 Lardner 3B 4 6 Callett C 3 8 Walker 1B 2 8 Hurley Jr. SS 5 6 Sheridan 2B 3 7 Fitzpatrick 1B 5 6 Cannon P 3 6 Lowduer 2B 1 10 Peterson CF 5 4 Parsons 3B 3 8 Christ C 2 5 Hurley Sr. 4F 4 6 McAvory 4F 3 4 Madderu CF 1 8 Dalton[?] SS 2 6 Bahanna RF 3 2 Magles RF 3 4 Totals 27 63 27 50 2. -

Auction Ends: June 18, 2009

AUCTION ENDS: JUNE 18, 2009 www.collect.com/auctions • phone: 888-463-3063 Supplement to Sports Collectors Digest e-mail: [email protected] CoverSpread.indd 3 5/19/09 10:58:52 AM Now offering Now accepting consignments for our August 27 auction! % Consignment deadline: July 11, 2009 0consignment rate on graded cards! Why consign with Collect.com Auctions? Ī COMPANY HISTORY: Ī MARKETING POWER: F +W Media has been in business More than 92,000 collectors see our since 1921 and currently has 700+ products every day. We serve 10 unique Steve Bloedow employees in the US and UK. collectible markets, publish 15 print titles Director of Auctions and manage 13 collectible websites. [email protected] Ī CUSTOMER SERVICE: Ī EXPOSURE: We’ve got a knowledgeable staff We reach 92,000+ collectors every day that will respond to your auction though websites, emails, magazines and questions within 24 hours. other venues. We’ll reach bidders no other auction house can. Bob Lemke Ī SECURITY: Ī EXPERTISE: Consignment Director Your treasured collectibles are We’ve got some of the most [email protected] securely locked away in a 20-x- knowledgeable experts in the hobby 20 walk-in vault that would make working with us to make sure every item most banks jealous. is described and marketed to its fullest, which means higher prices. Accepting the following items: Ī QUICK CONSIGNOR Ī EASE OF PAYMENT: Vintage Cards, PAYMENTS: Tired of having to pay with a check, Autographs, We have an 89-year track record money order or cash? Sure, we’ll accept Tickets, of always paying on time…without those, but you can also pay with major Game-Used Equipment, exception. -

Diapositiva 1

LA HISTORIA DEL JONRÓN CONFERENCIA DICTADA POR EL PROF. DR. CECILIO DÍAZ CARELA NOV. 2010, CURSA, UASD. STGO. R.D. PRIMERA PARTE . DEFINICION DEL JONRÓN Y DE ALGUNOS PARÁMETROS RELACIONADOS . LA HISTORIA DEL JONRÓN DESDE INICIOS DE LAS GRANDES LIGAS HASTA EL 2007. SEGUNDA PARTE. LA PARTICIPACION DE SAMUEL SOSA EN LA DÉCADA DEL JONRÓN . TERCERA PARTE. LA PARTICIPACION DOMINICANA EN EL BEISBÓL DE LAS LIGAS MAYORES. DEFINICIÓN DEL JONRÓN: . JONRÓN: Cuando el bateador puede avan- zar todas la bases hasta la goma. Esto se produce cuando la bola, generalmente bateada como elevado sale fuera del campo, en los límites válidos y establecidos como terreno bueno. Este vocablo es un anglicismo que se deriva del “Home Run”. LA FRECUENCIA JONRONERA: . Número de turnos por jonrón conectado (AB/HR). Mientras menor sea el número de turnos necesarios para conectar un jonrón mayor será la frecuencia de jonrones. EL GRAND SLAM: . Jonrón con las bases llenas. EL JONRÓN DE PIERNAS: . Batazo de imparable que le permite al bateador recorrer todas las bases sin detenerse y alcanzar la goma, sin ser puesto fuera. LOS JONRONES COLECTIVOS: . La sumatoria de los jonrones de todos los bateadores de un equipo durante una temporada. EL JONRONERO. EL bateador de jonrones. En las diferentes épocas por la que ha pasado el béisbol de las Grandes Ligas, el jonronero ha ido variando en el número de jonrones conec- tados por temporada. Hoy en día para ser considerado un jonronero se debe producir por los menos 30 HR. Aunque es posible que un bateador de 20 HR por temporada pueda alcanzar la connotación siempre que sea consistente y se ubique en el marco de una buena posición defensiva. -

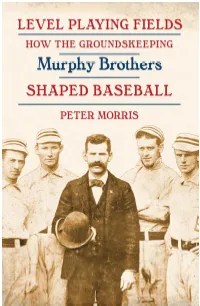

Level Playing Fields

Level Playing Fields LEVEL PLAYING FIELDS HOW THE GROUNDSKEEPING Murphy Brothers SHAPED BASEBALL PETER MORRIS UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS LINCOLN & LONDON © 2007 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska ¶ All rights reserved ¶ Manufactured in the United States of America ¶ ¶ Library of Congress Cata- loging-in-Publication Data ¶ Li- brary of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data ¶ Morris, Peter, 1962– ¶ Level playing fields: how the groundskeeping Murphy brothers shaped baseball / Peter Morris. ¶ p. cm. ¶ Includes bibliographical references and index. ¶ isbn-13: 978-0-8032-1110-0 (cloth: alk. pa- per) ¶ isbn-10: 0-8032-1110-4 (cloth: alk. paper) ¶ 1. Baseball fields— History. 2. Baseball—History. 3. Baseball fields—United States— Maintenance and repair. 4. Baseball fields—Design and construction. I. Title. ¶ gv879.5.m67 2007 796.357Ј06Ј873—dc22 2006025561 Set in Minion and Tanglewood Tales by Bob Reitz. Designed by R. W. Boeche. To my sisters Corinne and Joy and my brother Douglas Contents List of Illustrations viii Acknowledgments ix Introduction The Dirt beneath the Fingernails xi 1. Invisible Men 1 2. The Pursuit of Pleasures under Diffi culties 15 3. Inside Baseball 33 4. Who’ll Stop the Rain? 48 5. A Diamond Situated in a River Bottom 60 6. Tom Murphy’s Crime 64 7. Return to Exposition Park 71 8. No Suitable Ground on the Island 77 9. John Murphy of the Polo Grounds 89 10. Marlin Springs 101 11. The Later Years 107 12. The Murphys’ Legacy 110 Epilogue 123 Afterword: Cold Cases 141 Notes 153 Selected Bibliography 171 Index 179 Illustrations following page 88 1. -

Billy Sunday and the Masculinization of American Protestantism: 1896-1935

BILLY SUNDAY AND THE MASCULINIZATION OF AMERICAN PROTESTANTISM: 1896-1935 A. Cyrus Hayat Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History Indiana University December 2008 Accepted by the Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Kevin C. Robbins, PhD, Chair Erik L. Lindseth, PhD Master‟s Thesis Committee Philip Goff, PhD Jason S. Lantzer, PhD ii Dedication In loving memory of my grandmother, Agnes Van Meter McLane, who taught me to love and appreciate history. iii Acknowledgements I want to acknowledge and thank the great deal of people who provided assistance, support, and encouragement throughout the entire Thesis process, without these people, none of this would have ever been possible. My Thesis Advisor, Dr. Kevin Robbins challenged me and helped me become a better researcher and it was his enthusiasm that kept me constantly motivated. A special thank you is also due to Dr. Erik Lindseth for the years of help and assistance both during my undergraduate and graduate years here at IUPUI. Dr. Lindseth has been a wonderful mentor. I would also like to thank Dr. Jason Lantzer for his support over the years, as it was an Indiana History course that I took with him as an undergraduate that led to my interest in Hoosier History. I would also like to thank Dr. Philip Goff for providing me with a Religious Studies perspective and being a vital member of my committee. -

Challenging Nostalgia and Performance Metrics in Baseball

Challenging nostalgia and performance metrics in baseball Daniel J. Eck Department of Biostatistics, Yale University, New Haven, CT, 06510. [email protected] 1 Introduction It is easy to be blown away by the accomplishments of great old time baseball players when you look at their raw or advanced baseball statistics. These players produced mind-boggling numbers. For example, see Babe Ruth’s batting average and pitching numbers, Ty Cobb’s 1911 season, Walter Johnson’s 1913 season, Tris Speaker’s 1916 season, Rogers Hornsby’s 1925 season, and Lou Gehrig’s 1931 season. The statistical feats achieved by these players (and others) far surpass the statistics that recent and current players produce. At first glance it seems that players from the old eras were vastly superior to the players in more modern eras, but is this true? In this paper, we investigate whether baseball players from earlier eras of professional baseball are overrepresented among the game’s all-time greatest players according to popular opinion, performance metrics, and expert opinion. We define baseball players from earlier eras to be those that started their MLB careers in the 1950 season or before. This year is chosen because it coincides with the decennial US Census and is close to 1947, the year in which baseball became integrated. In this paper we do not compare baseball players via their statistical accomplishments. Such measures exhibit era biases that are confounded with actual performance. Consider the single season homerun record as an example. Before Babe Ruth, the single season homerun record was 27 by Ned Williamson in 1884. -

Outside the Lines of Gilded Age Baseball: Profits, Beer, and the Origins of the Brotherhood War Robert Allan Bauer University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 7-2015 Outside the Lines of Gilded Age Baseball: Profits, Beer, and the Origins of the Brotherhood War Robert Allan Bauer University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Sports Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Bauer, Robert Allan, "Outside the Lines of Gilded Age Baseball: Profits, Beer, and the Origins of the Brotherhood War" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1215. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1215 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Outside the Line of Gilded Age Baseball: Profits, Beer, and the Origins of the Brotherhood War Outside the Lines of Gilded Age Baseball: Profits, Beer, and the Origins of the Brotherhood War A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Robert A. Bauer Washington State University Bachelor of Arts in History and Social Studies, 1998 University of Washington Master of Education, 2003 University of Montana Master of Arts in History, 2006 July 2015 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ___________________________________ Dr. Elliott West Dissertation Director ___________________________________ _________________________________ Dr. Jeannie Whayne Dr. Patrick Williams Committee Member Committee Member Abstract In 1890, members of the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players elected to secede from the National League and form their own organization, which they called the Players League. -

Arthur Soden's Legacy: the Origins and Early History of Baseball's Reserve System Edmund P

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Journal Articles Publications 2012 Arthur Soden's Legacy: The Origins and Early History of Baseball's Reserve System Edmund P. Edmonds Notre Dame Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation Edmund P. Edmonds, Arthur Soden's Legacy: The Origins and Early History of Baseball's Reserve System, 5 Alb. Gov't L. Rev. 38 (2012). Available at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship/390 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTHUR SODEN'S LEGACY: THE ORIGINS AND EARLY HISTORY OF BASEBALL'S RESERVE SYSTEM Ed Edmonds* INTRODUCTION ............................................ 39 I. BASEBALL BECOMES OPENLY PROFESSIONAL.. .............. 40 A. The National Association of ProfessionalBase Ball Players .................................... 40 B. William Hulbert and the Creation of the National League..............................43 II. THE SODEN/O'ROURKE - GEORGE WRIGHT CONTROVERSY AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE RESERVE SYSTEM..........45 III. NEW COMPETITION: THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION AND THE UNION LEAGUE ........................... 51 IV. WARD ATTACKS THE RESERVE CLAUSE ......... ........... 66 A. The November 1887 League Meetings ..... ........ 70 B. Richter's Millennium Plan and Salary Classification.... 71 C. Brush ClassificationPlan ............. ........... 72 D. The Players' League..........................74 V. METROPOLITAN EXHIBITION COMPANY SEEKS INJUNCTION AGAINST WARD ...................................... 75 VI. Two PHILADELPHIA TEAMS FIGHT OVER BILL HALLMAN.......79 VII. ROUND TWO FOR THE GIANTS .................... -

Replay Summary.Xlsx

Rod Caborn Replays 1883 American Assn. (8) Pennant Cincinnati Reds 68-30, .694, +2 games RL 61-37, .622, - games Runner up Philadelphia Athletics 66-32, .673, -2 games RL 66-32, .673, +1 game MVP P Will White, Cincinnati 45-16, 1.38 Pitcher P Will White, Cincinnati 45-16, 1.38 Batting Average Ed Whiting, Louisville 0.371 Earned run average (98 inn) Will White, Cincinnati 1.38 On Base Pct Mike Moynahan, Phila A's 0.406 Wins Will White, Cincinnati 45 RBIs Harry Stovey, Phila A's 96 W-L Pct. Fred Corey, Phila. A's 13-3, .813 Base hits Mike Moynahan, Phila A's 136 Shutouts Will White, Cincinnati 13 2b Harry Stovey, Phila A's 34 Strikeouts Tim Keefe, NY Metros 464 3b Charles Smith, Columbus 21 Games appeared Tim Keefe, NY Metros 69 HR Harry Stovey, Phila A's 15 Innings pitched Tim Keefe, NY Metros 627 SB Bid McPhee, Cinc 52 Hits allowed Frank Mountain, Columbus 511 CS Cub Stricker, Phila A's 18 Total runs allowed Frank Mountain, Columbus 271 Runs scored Mike Moynahan, Phila A's 84 Earned runs allowed Frank Mountain, Columbus 207 BB Candy Nelson, NY Metros 43 Unearned runs allowed Frank Mountain, Columbus 74 Strikeouts Joe Battin, Pittsburgh 65 Games started Frank Mountain, Columbus 69 Sacrifices John Richmond, Columbus 18 Complete games Tim Keefe, NY Metros 55 Sac flies Bill Holbert, NY Metros 11 Bases on balls Frank Mountain, Columbus 175 At bats Bill Gleason, St. Louis 425 Home runs allowed Keefe, NYM, Sam Weaver, Lou 9 GIDP Three tied 10 Losses Frank Mountain, Columbus 41 Slugging High ERA (60 IP) Jack Neagle, Balt-Pitt 7.28 Saves 1883 National League (8) played 2013 Pennant Boston Beaneaters 62-36, .633, +2 games RL 63-35, .643, +4 games Runner up Providence Grays 58-38, .604, -2 games RL 58-40, .592, -5 games MVP Jim Whitney, Boston 38-18, ERA.188, hit .356 Pitcher Hoss Radbourn, Providence 46-24, 1.89, 57 CG, 8 Shut Batting Average Fred Dunlap, Cleve 0.373 Earned run average (98 inn) Jim Whitney, Boston 1.88 On Base Pct Fred Dunlap, Cleve 0.435 Wins Hoss Radbourn, Providence 46 RBIs Dan Brouthers, Buffalo 69 W-L Pct. -

SABR Baseball Biography Project | Society for American Baseball

THE ----.;..----- Baseball~Research JOURNAL Cy Seymour Bill Kirwin 3 Chronicling Gibby's Glory Dixie Tourangeau : 14 Series Vignettes Bob Bailey 19 Hack Wilson in 1930 Walt Wilson 27 Who Were the Real Sluggers? Alan W. Heaton and Eugene E. Heaton, Jr. 30 August Delight: Late 1929 Fun in St. Louis Roger A. Godin 38 Dexter Park Jane and Douglas Jacobs 41 Pitch Counts Daniel R. Levitt 46 The Essence of the Game: A Personal Memoir Michael V. Miranda 48 Gavy Cravath: Before the Babe Bill Swank 51 The 10,000 Careers of Nolan Ryan: Computer Study Joe D'Aniello 54 Hall of Famers Claimed off the Waiver List David G. Surdam 58 Baseball Club Continuity Mark Armour ~ 60 Home Run Baker Marty Payne 65 All~Century Team, Best Season Version Ted Farmer 73 Decade~by~Decade Leaders Scott Nelson 75 Turkey Mike Donlin Michael Betzold 80 The Baseball Index Ted Hathaway 84 The Fifties: Big Bang Era Paul L. Wysard 87 The Truth About Pete Rose :-.~~-.-;-;.-;~~~::~;~-;:.-;::::;::~-:-Phtltp-Sitler- 90 Hugh Bedient: 42 Ks in 23 Innings Greg Peterson 96 Player Movement Throughout Baseball History Brian Flaspohler 98 New "Production" Mark Kanter 102 The Balance of Power in Baseball Stuart Shapiro 105 Mark McGwire's 162 Bases on Balls in 1998 John F. Jarvis 107 Wait Till Next Year?: An Analysis Robert Saltzman 113 Expansion Effect Revisited Phil Nichols 118 Joe Wilhoit and Ken Guettler: Minors HR Champs Bob Rives 121 From A Researcher's Notebook Al Kermisch 126 Editor: Mark Alvarez THE BASEBALL RESEARCH JOURNAL (ISSN 0734-6891, ISBN 0-910137-82-X), Number 29. -

Babe Ruth: Milestone Home Runs

General Admission Home Run Milestones for Babe Ruth by S. Derby Gisclair Member, Society for American Baseball Research The home run prowess of George Herman “Babe” Ruth is legendary. So are many of the home runs that he hit – towering shots that cleared the outfield fences in ballparks across the league. And the frequency with which he produced home runs is astounding: one every 11.76 at-bats, or roughly one home rune every 3.5 games. How many times did newspapers across the country feature a headline like this? Many consider Ruth the greatest player of all-time. He is certainly the greatest home run hitter the game has ever seen, the accomplishments of others like Hank Aaron and Willie Mays not withstanding. Debates will rage among fans and historians. Arguments involving SABRmetrics and other analytical methods will attempt to settle the matter in favor of one position or another. The simple truth is that Babe Ruth hit home runs more frequently during his career than any other baseball player, and in so doing he changed the way the game of baseball was played. As the game teetered on the edge of collapse because of the Black Sox scandal after the 1919 World Series, it was the home run heroics of Babe Ruth that kept the fans coming to the ball park. He drew crowds wherever he played. He made the game fun again. The following are brief excerpts about several of the home run milestones in the 22-year career of Babe Ruth. S. Derby Gisclair 1 404 Notre Dame Street – PH1 New Orleans LA 70130 General Admission May 6, 1915 Babe Ruth hits his first major league home run at the Polo Grounds in New York in the third inning, batting ninth in the order for the Boston Red Sox.