Geoffrey-Clarke-Catalogue-Email.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artists' Lives

National Life Stories The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB Tel: 020 7412 7404 Email: [email protected] Artists’ Lives C466: Interviews complete and in-progress (at January 2019) Please note: access to each recording is determined by a signed Recording Agreement, agreed by the artist and National Life Stories at the British Library. Some of the recordings are closed – either in full or in part – for a number of years at the request of the artist. For full information on the access to each recording, and to review a detailed summary of a recording’s content, see each individual catalogue entry on the Sound and Moving Image catalogue: http://sami.bl.uk . EILEEN AGAR PATRICK BOURNE ELISABETH COLLINS IVOR ABRAHAMS DENIS BOWEN MICHAEL COMPTON NORMAN ACKROYD FRANK BOWLING ANGELA CONNER NORMAN ADAMS ALAN BOWNESS MILEIN COSMAN ANNA ADAMS SARAH BOWNESS STEPHEN COX CRAIGIE AITCHISON IAN BREAKWELL TONY CRAGG EDWARD ALLINGTON GUY BRETT MICHAEL CRAIG-MARTIN ALEXANDER ANTRIM STUART BRISLEY JOHN CRAXTON RASHEED ARAEEN RALPH BROWN DENNIS CREFFIELD EDWARD ARDIZZONE ANNE BUCHANAN CROSBY KEITH CRITCHLOW DIANA ARMFIELD STEPHEN BUCKLEY VICTORIA CROWE KENNETH ARMITAGE ROD BUGG KEN CURRIE MARIT ASCHAN LAURENCE BURT PENELOPE CURTIS ROY ASCOTT ROSEMARY BUTLER SIMON CUTTS FRANK AVRAY WILSON JOHN BYRNE ALAN DAVIE GILLIAN AYRES SHIRLEY CAMERON DINORA DAVIES-REES WILLIAM BAILLIE KEN CAMPBELL AILIAN DAY PHYLLIDA BARLOW STEVEN CAMPBELL PETER DE FRANCIA WILHELMINA BARNS- CHARLES CAREY ROGER DE GREY GRAHAM NANCY CARLINE JOSEFINA DE WENDY BARON ANTHONY CARO VASCONCELLOS -

Sculptors' Jewellery Offers an Experience of Sculpture at Quite the Opposite End of the Scale

SCULPTORS’ JEWELLERY PANGOLIN LONDON FOREWORD The gift of a piece of jewellery seems to have taken a special role in human ritual since Man’s earliest existence. In the most ancient of tombs, archaeologists invariably excavate metal or stone objects which seem to have been designed to be worn on the body. Despite the tiny scale of these precious objects, their ubiquity in all cultures would indicate that jewellery has always held great significance.Gold, silver, bronze, precious stone, ceramic and natural objects have been fashioned for millennia to decorate, embellish and adorn the human body. Jewellery has been worn as a signifier of prowess, status and wealth as well as a symbol of belonging or allegiance. Perhaps its most enduring function is as a token of love and it is mostly in this vein that a sculptor’s jewellery is made: a symbol of affection for a spouse, loved one or close friend. Over a period of several years, through trying my own hand at making rings, I have become aware of and fascinated by the jewellery of sculptors. This in turn has opened my eyes to the huge diversity of what are in effect, wearable, miniature sculptures. The materials used are generally precious in nature and the intimacy of being worn on the body marries well with the miniaturisation of form. For this exhibition Pangolin London has been fortunate in being able to collate a very special selection of works, ranging from the historical to the contemporary. To complement this, we have also actively commissioned a series of exciting new pieces from a broad spectrum of artists working today. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Gaffney, Sheila Elizabeth Embodied Dreaming as a sculptural practice informed by an idea in the psychoanalytical writings of Christopher Bollas. Original Citation Gaffney, Sheila Elizabeth (2019) Embodied Dreaming as a sculptural practice informed by an idea in the psychoanalytical writings of Christopher Bollas. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/35260/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Embodied Dreaming as a sculptural practice informed by an idea in the psychoanalytical writings of Christopher Bollas. SHEILA ELIZABETH GAFFNEY A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETH-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND TIIEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTHORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISH ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME If Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA.CT.................................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS •........••.••....••........•.•.•....•••.......•....•...• xi CHAPTER 1:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION 1 THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

Out There: Our Post-War Public Art Elisabeth Frink, Boar, 1970, Harlow

CONTENTS 6 28—29 Foreword SOS – Save Our Sculpture 8—11 30—31 Brave Art For A Brave New World Out There Now 12—15 32—33 Harlow Sculpture Town Get Involved 16—17 34 Art For The People Acknowledgements 18—19 Private Public Art 20—21 City Sculpture Project All images and text are protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced 22—23 in any form or by any electronic means, without written permission of the publisher. © Historic England. Sculpitecture All images © Historic England except where stated. Inside covers: Nicholas Monro, King Kong for 24—27 the City Sculpture Project, 1972, the Bull Ring, Our Post-War Public Art Birmingham. © Arnolfini Archive 4 Out There: Our Post-War Public Art Elisabeth Frink, Boar, 1970, Harlow Out There: Our Post-War Public Art 5 FOREWORD Winston Churchill said: “We shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us”. The generation that went to war against the Nazis lost a great many of their buildings – their homes and workplaces, as well as their monuments, sculptures and works of art. They had to rebuild and reshape their England. They did a remarkable job. They rebuilt ravaged cities and towns, and they built new institutions. From the National Health Service to the Arts Council, they wanted access-for-all to fundamental aspects of modern human life. And part of their vision was to create new public spaces that would raise the spirits. The wave of public art that emerged has shaped the England we live in, and it has shaped us. -

In a M Ed Ieval Space

ARK IN A MEDIEVAL SPACE SCULPTURE EXHIBITION at Chester Cathedral Education partner MODERN ART EXHIBITION CURATED BY GALLERY PANGOLIN 7 July - 15 October 2017 Chester Cathedral’s historic interior is an atmospheric and creative space. It will provide a fascinating and accessible context for viewing world-class sculpture as part of the ARK exhibition. The cathedral is the largest exhibition space within Chester. The largest FREE TO ENTER contemporary and modern sculpture exhibition to be held in the north west of England. ARK will feature 90 works of art by more than 50 celebrated sculptors, including Damien Hirst, Antony Gormley, Lynn Chadwick, Barbara Hepworth, Sarah Lucas, David Mach, Elisabeth Frink, Eduardo Paolozzi, Kenneth Armitage and Peter Randall-Page. AN EXCITING INTERNATIONAL ART EVENT & YOU CAN BE PART OF IT ARK is for everyone. For those new to sculpture and for aficionados. For adults and for children. For families. For you. We will be running an education programme alongside our exhibition. Join us for masterclasses, lectures and workshops for all ages. ARK SCULPTURE EXHIBITION Artists at Chester Cathedral Several sculptors will be showing brand new works of art whilst some will be on loan from private collections. It will be the first time these pieces have been seen together. ANTHONY ABRAHAMS ANN CHRISTOPHER ANTHONY ABRAHAMS ANN CHRISTOPHER KENNETH ARMITAGE GEOFFREY CLARKE KENNETH ARMITAGE GEOFFREY CLARKE BAILEY MICHAEL COOPER BAILEY MICHAEL COOPER BRUCE BEASLEY TERENCE COVENTRY BRUCE BEASLEY TERENCE COVENTRY NICK BIBBY -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETII-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND THEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTIIORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISII ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME III Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA eT...........................•.•........•........................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................... xi CHAPTER l:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION J THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

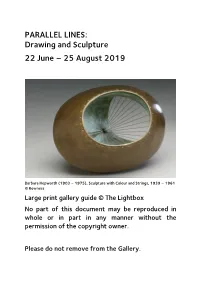

PARALLEL LINES: Drawing and Sculpture 22 June – 25 August 2019

PARALLEL LINES: Drawing and Sculpture 22 June – 25 August 2019 Barbara Hepworth (1903 – 1975), Sculpture with Colour and Strings, 1939 – 1961 © Bowness Large print gallery guide © The Lightbox No part of this document may be reproduced in whole or in part in any manner without the permission of the copyright owner. Please do not remove from the Gallery. The Ingram Collection Working in partnership with galleries, innovative spaces and new artistic talent, The Ingram Collection brings art to the widest possible audience. The Ingram Collection is one of the largest and most significant publicly accessible collections of Modern British Art in the UK, available to all through a programme of public loans and exhibitions. Founded in 2002 by serial entrepreneur and philanthropist Chris Ingram, the collection now spans over 100 years of British art and includes over 600 artworks. More than 400 of these are by some of the most important British artists of the twentieth century, amongst them Edward Burra, Lynn Chadwick, Elisabeth Frink, Barbara Hepworth and Eduardo Paolozzi. The main focus of the collection is on the art movements that developed in the early and middle decades of the twentieth century, and there is a particularly strong and in-depth holding of British sculpture. The Ingram Collection also holds a growing number of works by young and emerging artists, and in 2016 established its Young Contemporary Talent Purchase Prize in order to celebrate and support the work and early careers of UK art school graduates. The Royal Society of Sculptors The Royal Society of Sculptors is an artist led membership organisation. -

ROBERT ADAMS (British, 1917-1984)

ROBERT ADAMS (British, 1917-1984) “I am concerned with energy, a physical property inherent in metal, [and] in contrasts between linear forces and masses, between solid and open areas … the aim is stability and movement in one form.” (R. Adams, 1966, quoted in A. Grieve, 1992, pp. 109-111) Robert Adams was born in Northampton, England, in October 1917. He has been called “the neglected genius of post-war British sculpture” by critics. In 1937, Adams began attending evening classes in life drawing and painting at the Northampton School of Art. Some of Adam’s first-ever sculptures were also exhibited in London between 1942 and 1944 as part of a series of art shows for artists working in the Civil Defence, which Adams joined during the Second World War. He followed this with his first one-man exhibition at Gimpel Fils Gallery, London, in 1947, before starting a 10-year teaching career in 1949 at the Central School of Art and Design in London. It was during this time that Adams connected with a group of abstract painters – importantly Victor Pasmore, Adrian Heath and Kenneth and Mary Martin – finding a mutual interest in Constructivist aesthetics and in capturing movement. In 1948, Adams’ stylistic move towards abstraction was further developed when he visited Paris and seeing the sculpture of Pablo Picasso, Julio Gonzales, Constantine Brancusi and Henry Laurens. As such, Adams’ affiliation with his fellow English carvers, such as Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, extended only as far as an initial desire to carve in stone and wood. Unlike his contemporaries, Adams did not appear to show much interest in the exploration of the human form or its relationship to the landscape. -

UNIVERSITY of LEEDS the LIBRARY Archives of the Queen Square and Park Square Galleries, Special Collections MS 712 Part I: Collective Exhibitions

Handlist 74 UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS THE LIBRARY Archives of the Queen Square and Park Square Galleries, Special Collections MS 712 Part I: Collective exhibitions Mrs Sarah Gilchrist opened her commercial gallery in Queen Square, Leeds, in 1964; the enterprise flourished and she moved it to new premises in Park Square, Leeds, in 1968. She retired in 1978 though the gallery has continued under different aegis. In 1981 she was awarded an honorary degree by the University of Leeds and in the summer of 1984 through the timely intervention of Mr Stephen Chaplin of the University's Department of Fine Art, she most kindly agreed to give the accumulated archive of her galleries up to the date of her retirement to the Brotherton Library. The archive illustrates the relationship between artist and gallery, and between gallery and collector; it also illuminates taste and patronage in Yorkshire in the third quarter of the 20th century. This first part of a complete catalogue refers to collective exhibitions; further parts will deal. with one-man exhibitions, a picture lending scheme and other matters. Each catalogue will have indexes of exhibitors and of correspondents. This handlist was formerly issued in four parts, as handlists 74, 76, 84 and 85 Compiled October 1985 Digitised May 2004 CATALOGUE 1. First collective exhibition, 'Five Australian painters', April-May 1964 Work by:- Charles Blackman, Arthur Boyd, Louis James, John Perceval and Kenneth Rowell. 1-39 Correspondence, 1964. 51 ff. 40 Invitation to private view, 15 April 1964. 41 Priced catalogue, 1964. 42-43 Two photographs of exhibits, [1964]. 44-45 Mounted press-cuttings, 1964. -

Catalogue for Website.Indd

Cast in a Different Light: George Fullard and John Hoskin 2013 Introduction We follow with our eyes the development of the physical fact of a clenched hand, a crossed leg, a rising breast…until at the moment of recognition we realize that all this and more lies behind and makes up the reality of one woman or child during one second of their lives. And in this human tender sense, I would say that Fullard is one of the few genuine existentialist artists of today. He opens up for us the approach to and from the moment of awareness. John Berger on George Fullard, 1958 ¹ Vital and original…being a very distinct personality, he belongs to the animistic or magical trend in the now recognisable school of English sculpture. Herbert Read on John Hoskin, 1961 ² Woman with Earrings 1959 George Fullard Pencil At first glance, the artists featured in Cast in a Different Light have a good deal in common. Born in the early 1920s, they were both on active war service (Fullard in North Africa and Italy, Hoskin in Germany) and went on to make sculpture the focus of their creative practice. During the war years and immediately after, Henry Moore’s work attracted extraordinary international critical acclaim and, along with a generation of young sculptors, Fullard and Hoskin became part of what critics called the ‘phenomenon’ of postwar British sculpture.3 Through the 1960s, they both showed in gallery exhibitions such as the Tate’s British Sculpture in the Sixties (1965) and their work reached new audiences in the Arts Council’s iconic series of open-air sculpture exhibitions which toured public spaces and municipal parks up and down the country. -

Artists' Lives

National Life Stories The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB Tel: 020 7412 7404 Email: [email protected] Artists’ Lives C466: interviews complete and in-progress (at July 2015) Please note: access to each recording is determined by a signed RecordinG AGreement, aGreed by the artist and National Life Stories at the British Library. Some of the recordings are closed – either in full or in part – for a number of years at the request of the artist. For full information on the access to each recording, and to review a detailed summary of a recording’s content, see each individual catalogue entry on the Sound and MovinG ImaGe catalogue: http://sami.bl.uk . EILEEN AGAR FRANK BOWLING MILEIN COSMAN IVOR ABRAHAMS ALAN BOWNESS STEPHEN COX NORMAN ACKROYD IAN BREAKWELL TONY CRAGG NORMAN ADAMS GUY BRETT MICHAEL CRAIG-MARTIN ANNA ADAMS STUART BRISLEY JOHN CRAXTON CRAIGIE AITCHISON RALPH BROWN DENNIS CREFFIELD EDWARD ALLINGTON ANNE BUCHANAN CROSBY KEITH CRITCHLOW ALEXANDER ANTRIM STEPHEN BUCKLEY VICTORIA CROWE RASHEED ARAEEN ROD BUGG KEN CURRIE EDWARD ARDIZZONE LAURENCE BURT PENELOPE CURTIS DIANA ARMFIELD ROSEMARY BUTLER SIMON CUTTS KENNETH ARMITAGE JOHN BYRNE ALAN DAVIE MARIT ASCHAN SHIRLEY CAMERON DINORA DAVIES-REES FRANK AVRAY WILSON KEN CAMPBELL AILIAN DAY GILLIAN AYRES STEVEN CAMPBELL PETER DE FRANCIA WILLIAM BAILLIE CHARLES CAREY ROGER DE GREY PHYLLIDA BARLOW NANCY CARLINE JOSEFINA DE WILHELMINA BARNS- ANTHONY CARO VASCONCELLOS GRAHAM FRANCIS CARR TONI DEL RENZIO WENDY BARON B.A.R CARTER RICHARD DEMARCO GLENYS BARTON SEBASTIAN CARTER ROBYN DENNY