The Tsundur Moment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Official Website of ZILLA PRAJA PARISHAD-GUNTUR

THE RIGHT TO INFORMATION ACT, 2005 OBLIGATIONS OF PUBLIC AUTHORITIES INFORMATION HANDOOK [Refer to Chapter II Section 4(1) b of RTI Act, 2005] ZILLA PRAJA PARISHAD, GUNTUR. Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Background Please throw light on the background of this handbook - Right to Information Act and its key objectives. 1.2 Objective/purpose of this information handbook Describe the provisions of Section 4(1)(b) of the Act regarding mandatory suo motu disclosure of certain information by every public authority and how this guide is aimed at such disclosure and creating standardized information for easy access and understanding by the public.. 1.3 Who are the intended users of the handbook? Citizens, civil society organizations, public representatives, officers and employees of public authorities including Public Information Officers and Assistant Public Information Officers and Appellate Officers, Central and State Information Commissions etc. 1.4 Definitions of key terms Please provide definitions of keys terms used in this handbook. 1.5 Organization of information Describe how information is organized in this handbook and what is contained in different chapters. 1.6 Getting additional information Describe the sources, procedures and fees structure for getting information not available in this handbook. 1.7 Names & addresses of key contact points Give the names of key contact persons in case somebody wants to get more information on topics covered in the handbook as well as other information also. 2 Chapter 2 Organisation, Functions and Duties [Section 4(1)(b)(i)] 1. Particulars of the organization, functions and duties:- Sl. Name of the Address Functions Duties No. -

Name & Designation Of

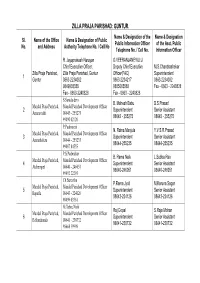

ZILLA PRAJA PARISHAD: GUNTUR. Name & Designation of the Name & Designation Sl. Name of the Office Name & Designation of Public Public Information Officer of the Asst. Public No. and Address Authority Telephone No. / Cell No Telephone No. / Cell No. Information Officer R. Jayaprakash Narayan G.VEERANJANEYULU Chief Executive Officer, Deputy Chief Executive M.S.Chandrashekar Zilla Praja Parishad, Zilla Praja Parishad, Guntur Officer(FAC) Superintendent 1 Guntur 0863-2234082 0863-2234217 0863-2234082 9849903355 9885665588 Fax - 0863 - 2240828 Fax - 0863-2240828 Fax - 0863 - 2240828 S.Sarada devi B. Mahesh Babu D.S.Prasad Mandal Praja Parishad, Mandal Parishad Development Officer 2 Superintendent Senior Assistant Amaravathi 08645 - 255275 08645 - 255275 08645 - 255275 99490 02120 P.Padmavati N. Ratna Manjula Y.V.S.R.Prasad Mandal Praja Parishad, Mandal Parishad Development Officer 3 Superintendent Senior Assistant Amruthaluru 08644 - 255235 08644-255235 08644-255235 99087 84555 P.S.Padmakar B. Rama Naik L.Subba Rao Mandal Praja Parishad, Mandal Parishad Development Officer 4 Superintendent Senior Assistant Atchempet 08640 - 246051 08640-246051 08640-246051 99492 22293 Ch.Suvartha P.Rama Jyoti M.Karuna Sagar Mandal Praja Parishad, Mandal Parishad Development Officer 5 Superintendent Senior Assistant Bapatla 08643 - 224126 08643-224126 08643-224126 98499 03361 G.Gabru Naik Raj Gopal S.Raja Mohan Mandal Praja Parishad, Mandal Parishad Development Officer 6 Superintendent Senior Assistant Bellamkonda 08641 - 238732 08641-238732 08641-238732 98668 -

Vemuru Assembly Andhra Pradesh Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/AP-089-0118 ISBN : 978-93-5293-035-7 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 158 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-9 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2014-PE, 2014-AE, 2009-PE and 2009-AE Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-14 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages by 15-16 Population Size | Sex Ratio -

Handbook of Statistics Guntur District 2015 Andhra Pradesh.Pdf

Sri. Kantilal Dande, I.A.S., District Collector & Magistrate, Guntur. PREFACE I am glad that the Hand Book of Statistics of Guntur District for the year 2014-15 is being released. In view of the rapid socio-economic development and progress being made at macro and micro levels the need for maintaining a Basic Information System and statistical infrastructure is very much essential. As such the present Hand Book gives the statistics on various aspects of socio-economic development under various sectors in the District. I hope this book will serve as a useful source of information for the Public, Administrators, Planners, Bankers, NGOs, Development Agencies and Research scholars for information and implementation of various developmental programmes, projects & schemes in the district. The data incorporated in this book has been collected from various Central / State Government Departments, Public Sector undertakings, Corporations and other agencies. I express my deep gratitude to all the officers of the concerned agencies in furnishing the data for this publication. I appreciate the efforts made by Chief Planning Officer and his staff for the excellent work done by them in bringing out this publication. Any suggestion for further improvement of this publication is most welcome. GUNTUR DISTRICT COLLECTOR Date: - 01-2016 GUNTUR DISTRICT HAND BOOK OF STATISTICS – 2015 CONTENTS Table No. ItemPage No. A. Salient Features of the District (1 to 2) i - ii A-1 Places of Tourist Importance iii B. Comparision of the District with the State 2012-13 iv-viii C. Administrative Divisions in the District – 2014 ix C-1 Municipal Information in the District-2014-15 x D. -

A Study on the Socio-Economic Conditions of Handloom Weavers

Journal of Rural Development, Vol. 33 No. (3) pp. 309-328 NIRD & PR, Hyderabad. 309 A STUDY ON THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC CONDITIONS OF HANDLOOM WEAVERS G. Naga Raju and K. Viyyanna Rao* ABSTRACT Handloom industry occupies an eminent place in preserving country’s heritage and culture, and hence plays a vital role in the economy of the country. Production in the handloom sector recorded a figure of 6900 million sq. meters in the year 2011-12, which is about 25 per cent over the production figure of 5493 million sq. meters recorded in the year 2003-04. As an economic activity, handloom sector occupies a place second only to agriculture in terms of employment. The sector with about 23.77 lakh handlooms provides employment to 43.31 lakh persons of whom, 77.9 per cent are women, and 28 per cent belong to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Handloom sector contributes nearly 15 per cent of the cloth production in the country and also contributes to the export earnings as 95 per cent of the world’s handwoven fabric comes from India. However, this sector is faced with various problems, such as, obsolete technology, unorganised production system, low productivity, inadequate working capital, conventional product range, and weak marketing links. Further, handloom sector has always been a weak competitor against powerloom and mill sectors. Against this backdrop, the present work attempts to make an indepth study into the life and misery of handloom households. It covers households located in select prominent areas of this sector. Introduction Study Area and Sample Selection The objective of this study is to examine Guntur district is one of the districts the socio-economic conditions of handloom having significant number of weaving weavers working in the sample area of Guntur population in Andhra Pradesh. -

Meos & MIS Co-Ordinators

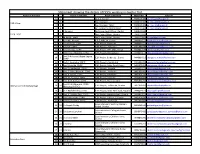

List of MEOs, MIS Co-orfinators of MRC Centers in AP Sl no District Mandal Name Designation Mobile No Email ID Remarks 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 Adilabad Adilabad Jayasheela MEO 7382621422 [email protected] 2 Adilabad Adilabad D.Manjula MIS Co-Ordinator 9492609240 [email protected] 3 Adilabad ASIFABAD V.Laxmaiah MEO 9440992903 [email protected] 4 Adilabad ASIFABAD G.Santosh Kumar MIS Co-Ordinator 9866400525 [email protected] [email protected] 5 Adilabad Bazarhathnoor M.Prahlad MEO(FAC) 9440010906 n 6 Adilabad Bazarhathnoor C.Sharath MISCo-Ord 9640283334 7 Adilabad BEJJUR D.SOMIAH MEO FAC 9440036215 [email protected] MIS CO- 8 Adilabad BEJJUR CH.SUMALATHA 9440718097 [email protected] ORDINATOR 9 Adilabad Bellampally D.Sridhar Swamy M.E.O 7386461279 [email protected] 10 Adilabad Bellampally L.Srinivas MIS CO Ordinator 9441426311 [email protected] 11 Adilabad Bhainsa J.Dayanand MEO 7382621360 [email protected] 12 Adilabad Bhainsa Hari Prasad.Agolam MIS Co-ordinator 9703648880 [email protected] 13 Adilabad Bheemini K.Ganga Singh M.E.O 9440038948 [email protected] 14 Adilabad Bheemini P.Sridar M.I.S 9949294049 [email protected] 15 Adilabad Boath A.Bhumareedy M.E.O 9493340234 [email protected] 16 Adilabad Boath M.Prasad MIS CO Ordinator 7382305575 17 Adilabad CHENNUR C.MALLA REDDY MEO 7382621363 [email protected] MIS- 18 Adilabad CHENNUR CH.LAVANYA 9652666194 [email protected] COORDINATOR 19 Adilabad Dahegoan Venkata Swamy MEO 7382621364 [email protected] 20 -

Statement Showing the Details of Ddos Working in Guntur Dist

Statement showing the details of DDOs working in Guntur Dist. Name of the Dept Name of the DDO Place of Working Mobile No email id 1 1 Dy.E.E, Guntur 9100121406 [email protected] 2 2 Exe. Engineer 9100121401 [email protected] R.W.S Dept 3 3 Exe. Engineer, Tenali 9100121403 [email protected] 4 4 Exe. Engineer, Narasaraopet 9100121402 [email protected] 1 K.Suhasini Dist.Coop.Audit Officer, Guntur 9100109186 Coop. Dept 2 Dist. Coop. Officer, Guntur 9100109185 5 3 M.Abdul Latieff Divl. Coop. Officer, Guntur 9985720889 [email protected]; 1 Kum.M.J.Nirmala P.D,D.W&C.W, Guntur 9440814511 [email protected] 6 2 S.V.Ramana, CDPO ICDS Project, Macherla 9440814512 [email protected] 7 3 J.Srivalli, CDPO ICDS Project, 75 Tyallur 9491051599 [email protected] 8 4 Smt.B.Sailaja, CDPO ICDS Project OPP: AMC, Tenali 9440814520 [email protected] 9 5 Smt.B.V.S.L.Bharathi, CDPO ICDS Project, Mangalagiri 9440814514 [email protected] Smt.Sk Ruksana Sultana Begum, 10 6 CDPO ICDS Project (Urban 1), , Guntur 9440814513 [email protected] 11 7 Smt.A. Anuradha, CDPO ICDS Project, Amruthalur 9491051598 [email protected] 12 8 Smt.B.Sujatha, CDPO ICDS Project, Main Road, Emani 9491051604 [email protected] 13 9 Smt.D.Geethanjali, CDPO ICDS Project, Bapatla 9440814516 [email protected] 14 10 Smt. G. Mary Bharathi, CDPO ICDS Project, Nallapdu 9491051601 [email protected] 15 11 Smt. B. Aruna, CDPO ICDS Project, Pallapatla 9491051597 [email protected] 16 12 Smt. -

S.No District Mandal UDISE Code School Name School Category

List of schools for opening of English Medium Parallel Sections at Class I during the year 2018 - 19 in Phase II School S.No District Mandal UDISE Code School Name Enrolment Category MPPS(ST) 1 GUNTUR ACHAMET 28170700603 Primary School 92 CHERUKUMPALEM UPPER Primary 2 GUNTUR ACHAMET 28170700605 MPUPS CHINTHAPALLI 89 School UPPER Primary 3 GUNTUR ACHAMET 28170700706 MPUPS KOTHAPALLI 99 School MPPS 4 GUNTUR ACHAMET 28170700805 Primary School 70 ATCHAMPETA(SSC) MPPS (BC) 5 GUNTUR ACHAMET 28170701004 Primary School 54 CHIGURUPADU MPPS (N SC) 6 GUNTUR ACHAMET 28170701102 Primary School 86 PEDAPALEM 7 GUNTUR ACHAMET 28170701205 MPUPS KONDURU Primary School 85 UPPER Primary 8 GUNTUR ACHAMET 28170701206 MPUPS NINDUJARLA 84 School 9 GUNTUR ACHAMET 28170701401 MPPS (MAIN) VELPUR Primary School 46 UPPER Primary 10 GUNTUR ACHAMET 28170701503 MPUPS RUDRAVARAM 61 School MPPS (SPL) 11 GUNTUR AMARAVATHI 28170900202 Primary School 102 MUNAGODU MPPS (MAIN) 12 GUNTUR AMARAVATHI 28170900301 Primary School 63 ATTALURU 13 GUNTUR AMARAVATHI 28170900305 MPPS (CD) JUPUDI Primary School 64 UPPER Primary 14 GUNTUR AMARAVATHI 28170900702 MPUPS DIDIGU 123 School MPPS (M) 15 GUNTUR AMARAVATHI 28170900804 Primary School 58 LINGAPURAM MPPS (HE) 16 GUNTUR AMARAVATHI 28170900904 Primary School 47 DHARANIKOTA UPPER Primary 17 GUNTUR AMARAVATHI 28170901001 MPPS(U) AMARAVATHI 55 School MPUPS UPPER Primary 18 GUNTUR AMARAVATHI 28170901102 74 VYKUNTAPURAM School UPPER Primary 19 GUNTUR AMARAVATHI 28170901505 MPUPS LEMALLE 64 School 20 GUNTUR AMRUTHALURU 28174900101 MPPS ITI -

Tlre Hon. Member from Been Murdered and Bodies. Sir. Daled Cum, The

287 Re. Bnrtd kflling of AUGUST 91, 1991 Re. Brutal kflllng of 2w HarlErns HaNm 12-00 hrs. inflicted on Harijans in my own RE. BRUTAL KILLING OF Constituency of Tenali in Andhra HARIJANS IN TSUNDUR VTLLAGE Pradesh. OF GUNTUR DISTRICT Sir, the incident occurred in village [Trmrska tion] Tsundur, is a naked attack on the SHRI RAM VILAS PASWAN very social order of the country. On (Roscra) : Mr. FSpeaker, Sir. I have the Sixth of this month, the upper given a notice that more than 20 caste people have organised an attack people belonging to Scheduled on the Harijans. (Interruptions) Castes have been killed in Tsundur MR. SPEAKER : That is not to village of Guntur district in Andhra be shown like that. Please fold it. Pradesh . (Interruptions). Even This is not done. yesterday our colleagues from Andhra Pradesh wen very much agitated. (Interruptions) People belonging to Scheduled Castes including 40 Dalirs have fled away PROF.VENKATESHWARLU UM- from the village. The State Govern- MAREDDY : Sir, in Guntur district ment was alre;.d? aware of the possi- about twenty Harijans have been bility of such an incident. If the Gov- cruelly murdered. The sequence of ernment wanted, it could avert events is that one Mr. Yocob, a Fair such a happening. The subject mat- Price Shop dealer was summoned by ter concerning the protection of the MRO. While Mr. Yocob was Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes going to MRO's Office, there was an is the responsibility of the Central attack on him by the upper caste Government. But I find that since the people. -

District Census Handbook, Guntur, Part XII-A & B, Series-2

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES 2 ANDHRA PRADESH DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK GUNTUR PARTS XII - A &. B VILLAGE &. TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE It TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT R.P.SINGH OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS ANDHRA PRADESH PUBLISHED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH 1995 FOREWORD Publication of the District Census Handbooks (DCHs) was initiated after the 1951 Census and is continuing since then with .some innovations/modifications after each decennial Census. This is the most valuable district level publication brought out by the Census Organisation on behalf of each State Govt./ Uni~n Territory a~ministratio~. It Inte: alia Provides data/information on· some of the baSIC demographic and soclo-economlc characteristics and on the availability of certain important civic amenities/facilities in each village and town of the respective ~i~tricts. This pub~i~ation has thus proved to be of immense utility to the pJanners., administrators, academiCians and researchers. The scope of the .DCH was initially confined to certain important census tables on population, economic and socia-cultural aspects as also the Primary Census Abstract (PCA) of each village and town (ward wise) of the district. The DCHs published after the 1961 Census contained a descriptive account of the district, administrative statistics, census tables and Village and Town Directories including PCA. After the 1971 Census, two parts of the District Census Handbooks (Part-A comprising Village and Town Directories and Part-B com~iSing Village and Town PCA) were released in all the States and Union Territories. Th ri art (C) of the District Census Handbooks comprising administrative statistics and distric census tables, which was also to be brought out, could not be published in many States/UTs due to considerable delay in compilation of relevant material. -

Guntur Distri Guntur District Gazette

GUNTUR DISTRICT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHROITY EXTRAORDINARY Local Gazette No. 944 Dated: 13 .03.2020 PROCEEDINGS OF THE COLLECTOR & DISTRICT MAGISTRATE, GUNTUR PRESENT: SRI I. SAMUEL ANAND KUMAR, I.A.S., Rc.No.3200/2019-G1 Dt. 17.02.2020. Sub:- Land Acquisition – House Sites providing under “Navaratnalu – Pedalandariki Illu” Scheme – Alapadu Village__- Tsundur_Mandal - “Voluntary Acquisition of Land” under Section 30-A of the RFCT LA R&R (AP Amendment) Act, 2018 (Act No.22 of 2018) to an extent of Ac. 1.50 cents in Survey Numbers 370/2,370/3,370/4,370/5,359/12 and 359/13 - Agreement entered into for acquisition of land under Rule 15 of Amendment Act No. 22 of 2018) - Orders – Issued. Read:- 1) RFCT LA R&R (AP Amendment) Act, 2018 (Act No.22 of 2018 and Rules framed vide G.O.Ms.No.562 Revenue (Land Acquisition) Dept., dt.13.11.2018) 2) Govt. Circular Memo.No.REV01-LANA0LAND(PM)/17/2019, dt.03.12.2019. 3) Form-A(1) filed by the Tahsildar, Tsundur through the Sub Collector, Tenali 4) Form-A(2) State Gazette No. REVO1-LANAOLAND/10/2020- LANDS-V , 07.01.2020 5) Form-C approved by the District Collector Guntur dt.30.01.2020 Published in District Gazette No. 274 dt. 31.01.2020 6) Form-G-III – Agreement with Land Owners. 7) Connected papers. &&& O R D E R: The Tahsildar Tsundur Mandal has filed Form-A(1) under Rule-4 of the RFCT LA R&R (Andhra Pradesh) Rules, 2018 for the exemption of Chapter-II & III of the Principal Act (I.e., Act No30 of 2013) to an extent of Ac.1.50 cents in Survey Numbers 370/2,370/3,370/4,370/5,359/12 and 359/13 of Alapadu Village for providing house sites under “Navaratnalau Pedalandariki Illu” scheme. -

In-Operative Accounts

List of unclaimed/ in-operative accounts 1 SAI BALAJI HOUSING (P) LTD SAI BALAJI NIVAS, DNO 4-5-4/8/C, NAVABHARAT NAGAR, III LANE, GUNTUR 2 SHINE CERAMICS PVT LTD SRI KRISHNA ESTATES,PRAKASAM ROAD, VIJAYAWADA DNO29-19-21, MOTHER & CHILD HOSPITAL, DORNAKAL ROAD, 3 MOTHER & CHILD HOSPITAL SURYARAOPET,VIJAYAWADA 4 SRI SRINIVASA ENTERPRISES PROP:G SAMBA SIVA RAO ,AJITH SINGH NAGAR, VIJAYAWADA 5 SREE SAI DURGA CONSTRUCTION HNO60-25-3, ROAD NO-3,SBICOLONY SIDDARTHA NAGAR, VIJAYAWADA 6 GURUKRUPA E-SIBAR CABEL NET 26-17-75, SIBAR TOWERS, BESANT ROAD, VIJAYAWADA 7 OSHOTECH WEIGHING SYSTEMS 11-4-90/A, HUDDUSAHIB STREET, VIJAYAWADA VETAPALEM MAIN ROAD,NEAR ANKAMMA TEMPLE, UNADAVALLI,GUNTUR 8 GOGINENI VIJAYA CHAND DIST USHA COMPLEX, DUBAGUNTAVARI STREET, ELURU ROAD, 9 ANDHRA TRADE CENTRE VIJAYAWADA 10 SRINVASA ENTERPRISES PROP:JSRINIVASA RAO, KANCHIKACHERLA PO&MD, KRISHNA DIST DNO23-6-35, KOMMURUVARI STREET, SATYANARAYANA PURAM, 11 VUMA HOLIDAY INNS LIMITED VIJAYAWADA KRISHNA DIST 12 M/SRAMAKRISHNA POULTRY FARMS TUKKULURU (POST) (VILLAGE) ,KRISHNA DIST 13 M/S MURALI KRISHNA TRADERS P/O AMURALI MOHAN RAO,OPP BABU OPTICALS, NUZIVID 14 SRI RAMAKRISHNA CLAY PRODUCT ANNAVARAM (POST)(VILLAGE) NUZVID (MD) 15 MANIKANTA TRADERS AGIRIPALLI (VILLAGE) (MANDAL) KRISHNA (DIST) 16 HARITHA INFORMATICS PVT LTD KATRENIPADU POST, MUSUNURU MANDAL , KRISHNA DIST 17 SRI VENKATESWARA ENTERPRISES PVENKATESWARA RAO, SRI VENKATESWARA ENTERPRISES, TANUKU 18 SK NAGUL MEERA SAHEB S/O CHINNA MASTAN SHEB,MELLAMPUDI, TADEPALLI , GUNTUR DIST 19 MOHAMMAD SALEEMUDDIN D/NO 12-39 ,GANDHI