Not There Yet — Canada's Implementation of the General

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suggestons. This Section Provides Information on Monitoring

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 389 406 PS 023 697 AUTHOR Biggs, Dinny; And Others TITLE In Our Own Backyard: A Teaching Guide for the Rights of the Child (Intended for Grade 1 through Grade 8). INSTITUTION United Nations Children's Fund Canada, Toronto (Ontario). REPORT NO ISBN-0-921564-09-0 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 43p. AVAILABLE FROMUNICEF Canada, 443 Mount Pleasant Road, Toronto, Ontario M4S 2L8, Canada ($10 Canadian). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Child Advocacy; Childhood Needs; *Childrens Rights; Child Responsibility; Child Welfare; Educational Resources; Elementary Education; Elementary School Students; Foreign Countries; *Learning Activities; Teaching Guides; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS Canada; *United Nations Convention on Rights of the Child AhSTRACT This guide presents children's rights as an issue directly affecting all children and one in which children's meaningful participation affects the responsibilities that accompany those rights. The handbook is organized around teaching ideas about the Convention on the Rights of the Child adopted by the United Nations in 1989 and later ratified by several member nations. Part 1, "Know Your Rights," suggests nine teaching tools and resources for a broad overview of children's rights and is followed by activity suggestons. This section provides information on monitoring students' learning, identifying students' location on the continuous process of inquiry, and selecting the appropriate tool for an entry point, an application, a summarizing activity, an action taking project, and so on. Part 2 provides activity ideas related to particular rights under five theme categories: mental and physical well-being, identity and expression, family and community, knowledge and culture, and law and protection. -

Who and What Gets Left Behind? Assessing Canada’S Domestic Status on the Sustainable Development Goals

GLOBAL ECONOMY & DEVELOPMENT WORKING PAPER 108 | OCTOBER 2017 WHO AND WHAT GETS LEFT BEHIND? ASSESSING CANADA’S DOMESTIC STATUS ON THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS John W McArthur Krista Rasmussen John W. McArthur is a senior fellow in the Global Economy and Development program at the Brookings Institution. Krista Rasmussen is a research analyst in the Global Economy and Development program at the Brookings Institution. Acknowledgements: The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mis- sion is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings pub- lication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not deter- mined or influenced by any donation. A full list of contributors to the Brookings Institution can be found in the Annual Report at https://www.brookings.edu/about-us/annual-report/. The authors thank Margaret Biggs, Kaysie Brown, George Ingram, Homi Kharas, Allison Loat, Lorenz Noe, Tony Pipa, and Brina Seidel for invaluable comments on earlier drafts of this paper. CONTENTS Introduction .......................................................................1 -

Reimagine Playbook

A BETTER FUTURE FOR YOUNG PEOPLE IN CANADA REIMAGINE PLAYBOOK SYSTEMIC RACISM MENTAL HEALTH EDUCATION CLIMATE CHANGE DEMOCRACY INDIGENOUS SOVEREIGNTY REIMAGINE PLAYBOOK UNICEF Canada extends our gratitude to: The young people who participated in the Stay In to Speak Out Sessions, and contributed to writing this Playbook. Our National Child Day partners: Assembly of Seven Generations, Boys and Girls Clubs of Canada, Equitas, First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, International Institute for Child Rights and Development, and The Students Commission of Canada Special thanks to: Climate Strike Canada, Justice for Children and Youth, Overlap Associates, and YMCA Canada. UNICEF Canada thanks the following partners who support One Youth and our efforts to advance the well-being of Canadian children and youth: Brookfield Partners Foundation Gail MacNaughton Intact Financial Corporation Lyle S. Hallman Foundation RBC Foundation in support of RBC Future Launch TD Securities Inc. The Lawson Foundation Anonymous UNICEF Canada recognizes that our work takes place on Indigenous territories across Turtle Island and pledges to work in reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. UNICEF Canada’s national office is situated on the ancestral, traditional territory of many nations including the Huron-Wendat, Petun, Seneca and, most recently, the Mississaugas of the New Credit. This territory is part of the Dish With One Spoon Wampum Belt Covenant, an agreement for all people to peaceably share and care for the resources around the Great Lakes. This territory is also covered by the Upper Canada Treaties. It is home to diverse First Nations, Metis and Inuit Peoples today, and we are grateful to live and work on this territory. -

YEAR in REVIEW Any Omissions Or Errors; Please Contact UNICEF Canada at 1 800 567 4483 If You Have Any Questions Or Changes

DONOR LISTING Day in, day out, UNICEF is working to ensure that children’s lives are changed for the better. UNICEF receives no COMMUNITY PARTNERS money from the UN and relies entirely on voluntary donations. It is your generosity that enables UNICEF to do its UNICEF Canada is grateful to its community partners 2 011 life-saving and life-changing work. UNICEF Canada is exceptionally grateful for the generous and continued support for their generous investment of time and resources. The of all of its donors. On behalf of the world’s children, thank you. following schools, events, clubs, and groups have each contributed $10,000 and above towards UNICEF’s work. The following list recognizes gifts made to UNICEF Canada between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2011. UNICEF Canada apologizes for YEAR IN REVIEW any omissions or errors; please contact UNICEF Canada at 1 800 567 4483 if you have any questions or changes. Anonymous (3) Sœurs de Saint-Joseph de Annapolis Capital Limited Saint-Hyacinthe INDIVIDUALS AND FOUNDATIONS Annual Golf Tournament Sisters of St. Joseph of the Diocese The following individuals and families have generously contributed $5,000 and above to UNICEF Canada. Argyle Secondary School of London BLG Annual Dodgeball Toronto District School Board Extravaganza Tuscany School Anonymous (31) Bill & Inge Christie Kerrie & Bob Hale Kathleen E. Marsman Foundation Utami © UNICEF Canada/2010/Sri Canadian Chinese Students' Ukrainian Canadian Congress 1337337 Alberta Inc. Bert & Hana Clark Kevin E. Hannah Ron & Tara Mathison Amarjeet S. Sandhu Art Charity Auction Charitable & Educational Trust 490824 Ontario Ltd. Carri Clarke & Reid Harbinger Foundation Susan & Dr. -

Donor Listing

DONOR LISTING Please accept our heartfelt thanks for your support. Together, we have saved children’s lives. COMMUNITY PARTNERS UNICEF Canada is grateful to its community partners The following list recognizes gifts made to UNICEF Canada between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2012. UNICEF Canada apologizes for any for their generous investment of time and resources. The omissions or errors; please contact UNICEF Canada at 1 800 567 4483 if you have any questions or changes. following schools, events, clubs, and groups have each contributed $5,000 and above towards UNICEF’s work. INDIVIDUALS AND FOUNDATIONS BLG Annual Dodgeball Sven's Mount Logan Summit The following individuals and families have generously contributed $5,000 and above to UNICEF Canada. Extravaganza Toronto District School Board Dr. Ruth Kurdyak Memorial Tuscany School Anonymous (31) Edward Assh Foundation David Johns & Cecilia Fernandes Ptarmigan Fund at The Calgary Fund at the Canadian Medical Ursulines de Québec School 490824 Ontario Ltd. N. Murray Edwards Kathryn Kennedy Foundation Foundation University of Calgary UNICEF Appleyard Foundation Charitable Foundation Alnashir, Sameer, & Alykhan Lakha Monique Quirion van Gent Chris Akkerman Elementary Club Dr. Dina El-Sahrigy Carrie & Kent Ferguson Jules Leclerc Riddell Family Charitable School University of Saskatchewan & Dr. Karim Aref Charles Fischer & Joanne Li Ka Shing (Canada) Foundation Foundation Crescentview School Employees STATEMENT OF REVENUE Drs. Paul & Karen Armstrong Cuthbertson Dr. William Libich Sue Riddell Rose & Michael Rose Crofton House School UNICEF Committees of: Clive & Ruth Beddoe Dr. Chen Fong Lycklama Family Fund at the Richard & Leena Sequeira Dream for Darfur Brantford AND EXPENSES (Year ended March 31) Allen W. -

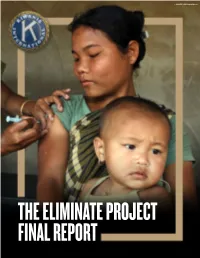

The Eliminate Project Final Report from Our Leaders

© UNICEF/UNI10404/Akash THE ELIMINATE PROJECT FINAL REPORT FROM OUR LEADERS Over the years, The Eliminate Project provided countless significant moments — causes for celebration, reasons to shed tears and opportunities to come together. Through it all, one conviction remained at the core of the campaign: No child should ever die from a preventable disease. Now that The Eliminate Project has come to a close, we are pleased to share the report that follows — because everything in it is a result of that first principle. PAUL PALAZZOLO ARTHUR RILEY 2009-10 Kiwanis 2020-21 Kiwanis International president International president When the Kiwanis family began the project in partnership with UNICEF, the vaccine for maternal and neonatal tetanus (MNT) had existed for decades. But newborn babies in 39 countries were suffering slow and painful deaths, with millions of others at risk, simply because they did not have access to quality healthcare services. It was an unacceptable fact in the world. Our partnership with UNICEF was an opportunity to change that fact — and to change the world. Eleven years later, we can look back with pride at what we’ve accomplished. But we should also remember that initial excitement and keep the determination to eliminate MNT in the countries where it remains a threat. As you read this report, we hope you’ll take pride in what Kiwanis has accomplished. We also hope you’ll remember the mothers and babies in countries where the work we’re funding continues. Kids need Kiwanis. The Eliminate Project stands as a continuing, worldwide testament to what we can achieve when we keep that truth close to our hearts. -

Conference Summary

1 F ACILITATING C HILD P ARTICIPATION IN I NTERNATIONAL C HILD P ROTECTION O CTOBER 5-6, 2015 R YERSON U NIVERSITY, C ANADA Conference Summary Prepared by Ilana Lockwood With notes from Nick Petten Introduction Facilitating Child Participation in International Child Protection took place at Ryerson University in Toronto on October 5th and 6th, 2015. The conference brought together about 60 individuals from around the world, representing various government departments, non- profit organizations, youth and academic institutions. (See Appendix C on p. 28 for list of participants.) The conference was chiefly funded by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada grant and coordinated by the Child Participation Working Group of the International Child Protection Network of Canada. The event would not have been possible without the generous, invaluable support of numerous organizations and individuals identified in Appendix D (p. 30). The goal of the event was to explore crucial issues at the intersection of child participation and child protection, share current practices and lessons learned, and identify key research and advocacy priorities for moving the field forward. The first day was dedicated to ethical, legal, and political tensions and priorities, while the second day focused on practical tensions and priorities, global trends affecting the field, and important areas of action emerging from this constellation of factors. A smaller group of conference participants began planning to follow up on conference outcomes on October 7 as described in a separate document. Youth participation was a critical component of the conference: a youth workshop was held on October 4th, where youth discussed the central questions of the conference to prepare their contributions to the event. -

Child Rights Education Toolkit: Rooting Child Rights in Early Childhood Education, Primary and Secondary Schools First Edition

Child Rights Education Toolkit: Rooting Child Rights in Early Childhood Education, Primary and Secondary Schools First Edition unite for children This fi rst edition of the Child Rights Education Toolkit is a provisional release prepared with a focus on experiences in countries with a UNICEF National Committee presence. It is important to note, however, that the principles and approaches contained in the Toolkit are applicable for all countries. We encourage both National Committee and UNICEF country offi ce colleagues to pilot the Toolkit and to apply its exercises and tools. We kindly request that you send any feedback or suggestions to the Child Rights Advocacy and Education Unit, Private Fundraising and Partnerships Division: [email protected] and [email protected]. Your inputs will inform the development of a second and fi nal edition of the Toolkit. © 2014 All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced, as a whole or in part, provided that acknowledgement of the source is made. Notifi cation of such would be appreciated. Published by: UNICEF Private Fundraising and Partnerships Division (PFP) Geneva, 2014 Child Rights Education Toolkit: Rooting Child Rights in Early Childhood Education, Primary and Secondary Schools First Edition 3 - A guide for UNICEF National Committees - 1st Edition Chapter 1 How to use this Toolkit Chapter 2 Understanding child rights education Chapter 3 Introducing the ‘CRE Tree’ Chapter 4 Whole school approach Chapter 5 Learning as a right Chapter 6 Learning about rights Chapter 7 Learning through rights Chapter 8 Learning for rights Chapter 9 Foundations and sustainability Chapter 10 Programme cycle management Glossary 4 - Child Rights Education Toolkit: Rooting Child Rights in Early Childhood Education, Primary and Secondary Schools Toolkit structure at a glance Introduction • Chapter 1 provides background on the Toolkit. -

Canada Child Rights and Business Assessment

Canada Child Rights and Business Assessment A guide for Canadian businesses on addressing children’s considerations and aligning with the Sustainable Development Goals © UNICEF/UN0339383/Frank Dejongh UNICEF/UN0339383/Frank © Contents 3 Introduction by the Working Group 4 Child Rights and Well-being in Canada and the World 5 Business and Child Rights 6 Principle 1: Commit to Respect and Support Child Rights 8 Principle 2: Contribute to the Elimination of Child Labour 10 Principle 3: Provide Decent Work for Young Workers, Parents and Caregivers 12 Principle 4: Ensure the Protection and Safety of Children 14 Principle 5: Ensure that Products and Services are Safe for Children 16 Principle 6: Use Marketing and Advertising that Respect and Support Child Rights 18 Principle 7: Respect Child Rights in Relation to the Environment and Land Use 20 Principle 8: Respect and Support Child Rights in Security Arrangements 22 Principle 9: Help Protect Children affected by Emergencies 24 Principle 10: Reinforce Government and Community Efforts to Protect Child Rights 26 Recommendations Any references made to a particular company do not imply endorsement of that company by UNICEF Canada or Global Compact Network Canada. Rather, these are intended to provide examples of how child rights are currently being addressed by companies, which others can learn from, adapt, and/or replicate. Introduction by the Working Group Children’s rights are everybody’s business. Respecting and Development Goals (SDGs), and the Canadian Index of Child supporting children’s rights are also good for business. As and Youth Well-being. This assessment aims not merely to Canadian companies with operations at home and abroad, inform, but to inspire Canadian businesses to identify, prevent, we recognize that over the lifetime of our businesses, our mitigate and account for how they address their salient impacts youngest stakeholders might be our most important. -

UNICEF Canada Magazine Annual Report 2014 Behind the Scenes at UNICEF Sarah Crowe Reports with Stories That Matter Keeping 4,000

UNICEF Canada Magazine Annual Report 2014 Behind the scenes at UNICEF Sarah Crowe reports with stories that matter Keeping 4,000 years of wisdom alive in Nunavut Protecting lives, one piece of paper at a time FOR EVERY CHILD UNICEF Canada Magazine CONTENTS ANNUAL REPORT 2014 Cover Story Spotlight In Canada Q&A Emergency Response From the Field Stories of Hope A message from President and CEO, David Morley UNICEF is the world’s leading child-focused humanitarian and development agency. 6 4/ THE 25TH TEAM Through innovative programs How UNICEF Canada – and 60 dynamic women – will save hank you for supporting UNICEF. It’s only thanks to caring and and advocacy work, we save the lives of women and children around the world committed friends like you that we can reach the poorest, most children’s lives and secure their vulnerable children in the world’s most inaccessible places. In this rights in virtually every country. Tissue of For Every Child, you’ll read about some of the ways you are helping to Our global reach, unparalleled save children’s lives and protect them from harm. influence on policymakers, and diverse partnerships make us an 6/ TELLING STORIES THAT MATTER instrumental force in shaping a Meet journalist, activist and UNICEF humanitarian worker Get a first-hand account of life in the field – from waves of sadness to moments world in which no child dies of Sarah Crowe of heroism – as seen through the eyes of international journalist and UNICEF a preventable cause. UNICEF is worker Sarah Crowe in “Telling Stories That Matter” (page 6). -

CANADIAN COMPANION Global Goal 12: Ensure Canada Ranks Our Kids Sustainable Production 6 Deserve Better

UNICEF REPORT CARD 14 eCeennanSTILLih . STUCK IN OH THECANADA! MIDDLE CANADIAN COMPANION Global Goal 12: Ensure Canada ranks Our kids sustainable production 6 deserve better. and consumption Global Goal 4: Ensure Canada ranks inclusive and equitable quality education for all 8 Global Goal 8: Promote full Canada ranks and productive employment eCeennanand decent worki h .for all 11 Global Goal 10: Reduce Canada ranks inequality within and among countries 14 Global Goal 11: Make OH CANADA!Canada ranks cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable 19 Global Goal 12: Ensure Canada ranks Our kids sustainable production and consumption 6 Global Goal 3: Ensure Canada ranks deserve better.healthy lives and promote well-being 29 Global Goal 4: Ensure Canada ranks inclusive and equitable quality education for all 8 Global Goal 1: End poverty Canada ranks in all its forms everywhere 32 Global Goal 8: Promote full Canada ranks and productive employment Global Goal 2: End hunger, Canada ranks and decent work for all 11 UNICEF REPORT CARD 14 achieve food security and Canadian Companion improved nutrition 37 Global Goal 10: Reduce Canada ranks inequality within and Global Goal 16: Promote Canada ranks among countries 14 unicef.ca/irc14 peaceful and inclusive societiesunicef.ca/IRC14 37 Global Goal 11: Make Canada ranks cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable 19 Global Goal 3: Ensure Canada ranks healthy lives and promote well-being 29 Global Goal 1: End poverty Canada ranks in all its forms everywhere 32 Global Goal 2: End hunger, Canada ranks UNICEF REPORT CARD 14 achieve food security and Canadian Companion improved nutrition 37 Global Goal 16: Promote Canada ranks unicef.ca/irc14 peaceful and inclusive societies 37 Report Card 14 Canadian Companion Oh Canada! Our kids deserve better CANADIAN COMPANION TO UNICEF REPORT CARD 14 Oh Canada! Our kids deserve better Visit unicef.ca/irc14 for UNICEF Report Card 14, Building our Future: Children and Sustainable Development Goals in Rich Countries, infographics and background papers. -

Fall 2020 Newsletter.Pub

South Collegiate Alumni Association Fall 2020 Virtus Repulsae Nescia Sordidae A STORY GROWS WITH THE HELP OF A DUTCH CONNECTION by Connie (Woods) Weir (‘66) (Note: This article first appeared in the November issue of the Wortley Villager) It’s now more than three years since the SCAA published Knowing No Defeat, a memorial tribute to the 57 alumni who lost their lives in military service during World War II. Of the 300 copies printed, only a handful remain to be sold. As gratifying as this sales success is, the most rewarding result of our efforts has been in terms of the human responses, which we are still continuing to receive. On August 28th, I received an email fom Cathy Wood, Managing Editor of the Wortley Villager, after she saw a post on the Facebook Group “If You Grew Up In London, Ontario, You Will Remember When…”. This post, written by a young man in the Netherlands, Jesse Verkruyssen, began with “Hi Canadians! I have a question for you.” Having heard stories from his grandparents about how bad the war was, Jesse said he had “always wanted to somehow thank the men who fought for our freedom”, so decided to “adopt” two WW II war graves. One of the graves that Jesse assumed the care of belonged to Leonard Albert Stock, a 19-year-old Canadian soldier from London, who died in 1941 and was buried in Eindhoven Cemetery, near Woensel. Although he had access to Leonard’s war records, he had little information about Leonard’s family and wanted to learn more.