The CDC Guide to Breastfeeding Interventions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Breastfeeding Questions

Common Breastfeeding Questions How often should my baby nurse? Your baby should nurse 8-12 times in 24 hours. Baby will tell you when he’s hungry by “rooting,” sucking on his hands or tongue, or starting to wake. Just respond to baby’s cues and latch baby on right away. Every mom and baby’s feeding patterns will be unique. Some babies routinely breastfeed every 2-3 hours around the clock, while others nurse more frequently while awake and sleep longer stretches in between feedings. The usual length of a breastfeeding session can be 10-15 minutes on each breast or 15-30 minutes on only one breast; just as long as the pattern is consistent. Is baby getting enough breastmilk? Look for these signs to be sure that your baby is getting enough breastmilk: Breastfeed 8-12 times each day, baby is sucking and swallowing while breastfeeding, baby has 3- 4 dirty diapers and 6-8 wet diapers each day, the baby is gaining 4-8 ounces a week after the first 2 weeks, baby seems content after feedings. If you still feel that your baby may not be getting enough milk, talk to your health care provider. How long should I breastfeed? The World Health Organization and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends mothers to breastfeed for 12 months or longer. Breastmilk contains everything that a baby needs to develop for the first 6 months. Breastfeeding for at least the first 6 months is termed, “The Golden Standard.” Mothers can begin breastfeeding one hour after giving birth. -

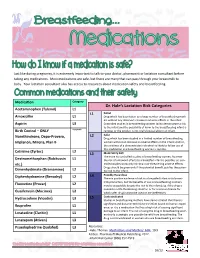

Dr. Hale's Lactation Risk Categories

Just like during pregnancy, it is extremely important to talk to your doctor, pharmacist or lactation consultant before taking any medications. Most medications are safe, but there are many that can pass through your breastmilk to baby. Your lactation consultant also has access to resources about medication safety and breastfeeding. Medication Category Dr. Hale’s Lactation Risk Categories Acetaminophen (Tylenol) L1 L1 Safest Amoxicillin L1 Drug which has been taken by a large number of breastfeeding moth- ers without any observed increase in adverse effects in the infant. Aspirin L3 Controlled studies in breastfeeding women fail to demonstrate a risk to the infant and the possibility of harm to the breastfeeding infant is Birth Control – ONLY Acceptable remote; or the product is not orally bioavailable in an infant. L2 Safer Norethindrone, Depo-Provera, Drug which has been studied in a limited number of breastfeeding Implanon, Mirena, Plan B women without an increase in adverse effects in the infant; And/or, the evidence of a demonstrated risk which is likely to follow use of this medication in a breastfeeding woman is remote. Cetrizine (Zyrtec) L2 L3 Moderately Safe There are no controlled studies in breastfeeding women, however Dextromethorphan (Robitussin L1 the risk of untoward effects to a breastfed infant is possible; or, con- etc.) trolled studies show only minimal non-threatening adverse effects. Drugs should be given only if the potential benefit justifies the poten- Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) L2 tial risk to the infant. L4 Possibly Hazardous Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) L2 There is positive evidence of risk to a breastfed infant or to breast- milk production, but the benefits of use in breastfeeding mothers Fluoxetine (Prozac) L2 may be acceptable despite the risk to the infant (e.g. -

Chapter Nineteen Breastfeeding Education and Support

Chapter Nineteen Breastfeeding Education and Support Chapter Nineteen – Breastfeeding Education and Support Contents Chapter Nineteen Breastfeeding Education and Support .................................................................... 19-1 Overview .............................................................................................................................................. 19-6 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 19-6 In This Chapter ................................................................................................................................. 19-6 Section A Breastfeeding Promotion ..................................................................................................... 19-7 Staffing ............................................................................................................................................. 19-7 Funding ............................................................................................................................................ 19-7 WIC Breastfeeding Committee ........................................................................................................ 19-7 Clinic Environment ........................................................................................................................... 19-7 Breastfeeding Messages and Resources ......................................................................................... -

Melasma (1 of 8)

Melasma (1 of 8) 1 Patient presents w/ symmetric hyperpigmented macules, which can be confl uent or punctate suggestive of melasma 2 DIAGNOSIS No ALTERNATIVE Does clinical presentation DIAGNOSIS confirm melasma? Yes A Non-pharmacological therapy • Patient education • Camoufl age make-up • Sunscreen B Pharmacological therapy Monotherapy • Hydroquinone or • Tretinoin TREATMENT Responding to No treatment? See next page Yes Continue treatment © MIMSas required Not all products are available or approved for above use in all countries. Specifi c prescribing information may be found in the latest MIMS. B94 © MIMS 2019 Melasma (2 of 8) Patient unresponsive to initial therapy MELASMA A Non-pharmacological therapy • Patient education • Camoufl age make-up • Sunscreen B Pharmacological therapy Dual Combination erapy • Hydroquinone plus • Tretinoin or • Azelaic acid Responding to Yes Continue treatment treatment? as required No A Non-pharmacological therapy • Patient education • Camoufl age make-up • Sunscreen • Laser therapy • Dermabrasion B Pharmacological therapy Triple Combination erapy • Hydroquinone plus • Tretinoin plus • Topical steroid Chemical peels 1 MELASMA • Acquired hyperpigmentary skin disorder characterized by irregular light to dark brown macules occurring in the sun-exposed areas of the face, neck & arms - Occurs most commonly w/ pregnancy (chloasma) & w/ the use of contraceptive pills - Other factors implicated in the etiopathogenesis are photosensitizing medications, genetic factors, mild ovarian or thyroid dysfunction, & certain cosmetics • Most commonly aff ects Fitzpatrick skin phototypes III & IV • More common in women than in men • Rare before puberty & common in women during their reproductive years • Solar & ©ultraviolet exposure is the mostMIMS important factor in its development Not all products are available or approved for above use in all countries. -

Breastfeeding Is Best Booklet

SOUTH DAKOTA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH WIC PROGRAM Benefits of Breastfeeding Getting Started Breastfeeding Solutions Collecting and Storing Breast Milk Returning to Work or School Breastfeeding Resources Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine www.bfmed.org American Academy of Pediatrics www2.aap.org/breastfeeding Parenting website through the AAP www.healthychildren.org/English/Pages/default.aspx Breastfeeding programs in other states www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/CDC_BFWorkplaceSupport.pdf Business Case for Breastfeeding www.womenshealth.gov/breastfeeding/breastfeeding-home-work- and-public/breastfeeding-and-going-back-work/business-case Centers for Disease Control and Prevention www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) www.toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/newtoxnet/lactmed.htm FDA Breastpump Information www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ HomeHealthandConsumer/ConsumerProducts/BreastPumps Healthy SD Breastfeeding-Friendly Business Initiative www.healthysd.gov/breastfeeding International Lactation Consultant Association www.ilca.org/home La Leche League www.lalecheleague.org MyPlate for Pregnancy and Breastfeeding www.choosemyplate.gov/moms-pregnancy-breastfeeding South Dakota WIC Program www.sdwic.org Page 1 Breastfeeding Resources WIC Works Resource System wicworks.fns.usda.gov/breastfeeding World Health Organization www.who.int/nutrition/topics/infantfeeding United States Breastfeeding Committee - www.usbreastfeeding.org U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/ Office of Women’s Health www.womenshealth.gov/breastfeeding -

The Key to Increasing Breastfeeding Duration: Empowering the Healthcare Team

The Key to Increasing Breastfeeding Duration: Empowering the Healthcare Team By Kathryn A. Spiegel A Master’s Paper submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Public Health in the Public Health Leadership Program. Chapel Hill 2009 ___________________________ Advisor signature/printed name ________________________________ Second Reader Signature/printed name ________________________________ Date The Key to Increasing Breastfeeding Duration 2 Abstract Experts and scientists agree that human milk is the best nutrition for human babies, but are healthcare professionals (HCPs) seizing the opportunity to promote, protect, and support breastfeeding? Not only are HCPs influential to the breastfeeding dyad, they hold a responsibility to perform evidence-based interventions to lengthen the duration of breastfeeding due to the extensive health benefits for mother and baby. This paper examines current HCPs‘ education, practices, attitudes, and extraneous factors to surface any potential contributing factors that shed light on necessary actions. Recommendations to empower HCPs to provide consistent, evidence-based care for the breastfeeding dyad include: standardized curriculum in medical/nursing school, continued education for maternity and non-maternity settings, emphasis on skin-to-skin, enforcement of evidence-based policies, implementation of ‗Baby-Friendly USA‘ interventions, and development of peer support networks. Requisite resources such as lactation consultants as well as appropriate medication and breastfeeding clinical management references aid HCPs in providing best practices to increase breastfeeding duration. The Key to Increasing Breastfeeding Duration 3 The key to increasing breastfeeding duration: Empowering the healthcare team During the colonial era, mothers breastfed through their infants‘ second summer. -

Running Head: BREASTFEEDING SUPPORT 1 Virtual Lactation

Running Head: BREASTFEEDING SUPPORT 1 Virtual Lactation Support for Breastfeeding Mothers During the Early Postpartum Period Shakeema S. Jordan College of Nursing, East Carolina University Doctor of Nursing Practice Program Dr. Tracey Bell April 30, 2021 Running Head: BREASTFEEDING SUPPORT 2 Notes from the Author I want to express a sincere thank you to Ivy Bagley, MSN, FNP-C, IBCLC for your expertise, support, and time. I also would like to send a special thank you to Dr. Tracey Bell for your support and mentorship. I dedicate my work to my family and friends. I want to send a special thank you to my husband, Barry Jordan, for your support and my two children, Keith and Bryce, for keeping me motivated and encouraged throughout the entire doctorate program. I also dedicate this project to many family members and friends who have supported me throughout the process. I will always appreciate all you have done. Through my personal story and the doctorate program journey, I have learned the importance of breastfeeding self-efficacy and advocacy. I understand the impact an adequate support system, education, and resources can have on your ability to reach your individualized breastfeeding goals. Running Head: BREASTFEEDING SUPPORT 3 Abstract Breastmilk is the clinical gold standard for infant feeding and nutrition. Although maternal and child health benefits are associated with breastfeeding, national, state, and local rates remain below target. In fact, 60% of mothers do not breastfeed for as long as intended. During the early postpartum period, mothers cease breastfeeding earlier than planned due to common barriers such as lack of suckling, nipple rejection, painful breast or nipples, latching or positioning difficulties, and nursing demands. -

Breastfeeding Guide Lactation Services Department Breastfeeding: Off to a Great Start

Breastfeeding Guide Lactation Services Department Breastfeeding: Off to a Great Start Offer to feed your baby: • when you see and hear behaviors that signal readiness to feed. Fussiness and hand to mouth motions may signal hunger. At other times, your baby is asking to be held or changed. He may be showing signs of being over-stimulated or tired. • until satisfied. In the early weeks and months, feeding lengths vary from 10 to 40 minutes per side. Offer both breasts at each feeding. Your baby may not always take the second side. Expect your baby to cluster feed to increase your milk supply, especially when going through growth spurts. • at least every 1 ½ to 3 hours during the day and a little less frequently at night. Time feedings from the start of one feeding to the start of the next. Most mothers are able to produce enough milk and do NOT need to supplement with formula. • using proper positioning. Turn your baby toward you while breastfeeding. With a wide open mouth, she takes in the areola along with the nipple. The cheeks and chin are touching the breast. Expect your baby to pause between suckle bursts. It is okay to gently stimulate her to suckle throughout the feeding. Your baby is getting enough breastmilk IF: • you hear audible swallows when your baby pauses between suckle bursts. You will hear them more often as your milk changes 24 Hours from colostrum to mature milk. st at least 6 feedings • there are 6 or more wet diapers by day 6. This number will 1 1 wet and 1 stool remain fairly constant after the first week. -

Tongue and Lip Ties: Best Evidence June 16, 2015

Tongue and Lip Ties: Best Evidence June 16, 2015 limited elevation in tongue tied baby Tongue and Lip Ties: Best Evidence By: Lee-Ann Grenier Tongue and lip tie (often abbreviated to TT/LT) have become buzzwords among lactation consultants bloggers and new mothers. For many these are strange new words despite the fact that it is a relatively common condition. Treating tongue tie fell out of medical favour in the early 1950s. In breastfeeding circles, it was talked about occasionally, but until recently few health care professionals screened babies for tongue tie and it was frequently overlooked as a cause of common breastfeeding difficulties. In the last few years tongue tie and the related condition lip tie have exploded into the consciousness of mothers and breastfeeding helpers. So why all the fuss about tongue and lip ties all of a sudden? Tongue tie seems to be a relatively common problem, affecting 4-11%1 of the population and it can have a drastic impact on breastfeeding. The presence of tongue tie triples the risk of weaning in the first week of life.2 Here in Alberta it has been challenging to find competent assessment and treatment, prompting several Alberta mothers and their babies to fly to New York in 2011 and 2012 to receive treatment. The dedication and persistence of these mothers has spurred action on providing education and treatment options for Alberta families. In August of 2012, The Breastfeeding Action Committee of Edmonton (BACE) brought Dr. Lawrence Kotlow to Edmonton to provide information and training to area health care providers. -

Massachusetts Breastfeeding Resource Guide

Massachusetts Breastfeeding Resource Guide 2008 Edition © 254 Conant Road Weston, MA 02493 781 893-3553 Fax 781 893-8608 www.massbfc.org Massachusetts Breastfeeding Coalition Leadership Chair Board Member Melissa Bartick, MD, MS Lauren Hanley, MD Treasurer Board Member Gwen MacCaughey Marsha Walker, RN, IBCLC NABA, Lactation Associates Clerk Xena Grossman, RD, MPH Board Member Anne Merewood, MPH, IBCLC Board Member Lucia Jenkins, RN, IBCLC La Leche League of MA RI VT 10th edition (2008) Compiled and edited by Rachel Colchamiro, MPH, RD, LDN, CLC and Jan Peabody Cover artwork courtesy of Peter Kuper Funding for the printing and distribution of the Massachusetts Breastfeeding Resource Guide is provided by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health-Bureau of Family and Community Health, Nutrition Division. Permission is granted to photocopy this guide except for the three reprinted articles from the American Academy of Pediatrics and two articles from the American Academy of Family Physicians. Adapted from the Philadelphia Breastfeeding Resource Handbook. hhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhTable of Contents Organizational statements on breastfeeding…………………………………………………………….2 Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk, American Academy of Pediatrics…………………….6 Breastfeeding Position Paper, American Academy of Family Physicians……………………...…19 Breastfeeding initiatives………………………...……………………………………………………...…37 Breastfeeding support and services…………………………………………...………………...…....…39 La Leche League International leaders………….…………………………………………………...….40 Lactation consultants………………………………………………………………………………….…..44 -

Breastfeeding Contraindications

WIC Policy & Procedures Manual POLICY: NED: 06.00.00 Page 1 of 1 Subject: Breastfeeding Contraindications Effective Date: October 1, 2019 Revised from: October 1, 2015 Policy: There are very few medical reasons when a mother should not breastfeed. Identify contraindications that may exist for the participant. Breastfeeding is contraindicated when: • The infant is diagnosed with classic galactosemia, a rare genetic metabolic disorder. • Mother has tested positive for HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Syndrome) or has Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). • The mother has tested positive for human T-cell Lymphotropic Virus type I or type II (HTLV-1/2). • The mother is using illicit street drugs, such as PCP (phencyclidine) or cocaine (exception: narcotic-dependent mothers who are enrolled in a supervised methadone program and have a negative screening for HIV and other illicit drugs can breastfeed). • The mother has suspected or confirmed Ebola virus disease. Breastfeeding may be temporarily contraindicated when: • The mother is infected with untreated brucellosis. • The mother has an active herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection with lesions on the breast. • The mother is undergoing diagnostic imaging with radiopharmaceuticals. • The mother is taking certain medications or illicit drugs. Note: mothers should be provided breastfeeding support and a breast pump, when appropriate, and may resume breastfeeding after consulting with their health care provider to determine when and if their breast milk is safe for their infant and should be provided with lactation support to establish and maintain milk supply. Direct breastfeeding may be temporarily contraindicated and the mother should be temporarily isolated from her infant(s) but expressed breast milk can be fed to the infant(s) when: • The mother has untreated, active Tuberculosis (TB) (may resume breastfeeding once she has been treated approximately for two weeks and is documented to be no longer contagious). -

Zero to Three

zero to three *.C'T-RATEG I C P LAN Sar~taFe County Maternal and child I iealth io~rr~cil syt It, J 2002 DEDICATION This Zero to Three Strategic Plan is dedicated to Cameron Lauren Gonzales and all her young peers in Santa Fe County. With special thanks to her father Commissioner Javier Gonzales And to Commissioner Paul Campos Commissioner Paul Duran commissioner Jack Sullivan Commissioner Marcos Trujao Who have resolved to "Stand For Children" And Whose support has created a plan to ensure that children and families will have opportunities to thrive in Santa Fe County. SANTA FE COUNTY ZERO TO THREE STRATEGIC PLAN 2002-2006 a a Presented by the Santa Fe County Maternal and Child Health Council /' \ L To create a a funding to f amily-frilation and ' , ,44*~.'. !e 0-3 plan v -.. , " - ' 4- .? Strategic Issues Criteria for 5ucce55 Strategrc 155ue5are cruc~alto effect~veimplementat~on. Securing adequate sustainable support ,ratcgres In th15plan 5tr1vetoward these rdeals iildren and their parents will be valued as a unit Establishing leadership and responsibility for eald treated with dignity and Priority Area I irents/families will be included in the planning of Building coalitions among stakeholders (provider5ources and services. and community) 1 and ~chpriority area will have strong, consistent for child-friendly, fa$dership from agenciesand occurring friendly policies 3 lmmunity networks. Creating and funding a 0-3 marketing plar,llaborations and partmrship5 will be a keystone bilingual public relations and educational materia , success. ;I Leveraging funding from coalitions for recruitme]stainable funding will be secured. :I and training of professional and lay/community gal status, class and race will not be deterrents providers (home visitors and child caregivers) accessing services.