For Whom the Bell Miner's Toll

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Printable PDF Format

Field Guides Tour Report Australia Part 2 2019 Oct 22, 2019 to Nov 11, 2019 John Coons & Doug Gochfeld For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Water is a precious resource in the Australian deserts, so watering holes like this one near Georgetown are incredible places for concentrating wildlife. Two of our most bird diverse excursions were on our mornings in this region. Photo by guide Doug Gochfeld. Australia. A voyage to the land of Oz is guaranteed to be filled with novelty and wonder, regardless of whether we’ve been to the country previously. This was true for our group this year, with everyone coming away awed and excited by any number of a litany of great experiences, whether they had already been in the country for three weeks or were beginning their Aussie journey in Darwin. Given the far-flung locales we visit, this itinerary often provides the full spectrum of weather, and this year that was true to the extreme. The drought which had gripped much of Australia for months on end was still in full effect upon our arrival at Darwin in the steamy Top End, and Georgetown was equally hot, though about as dry as Darwin was humid. The warmth persisted along the Queensland coast in Cairns, while weather on the Atherton Tablelands and at Lamington National Park was mild and quite pleasant, a prelude to the pendulum swinging the other way. During our final hours below O’Reilly’s, a system came through bringing with it strong winds (and a brush fire warning that unfortunately turned out all too prescient). -

Non-Lethal Foraging by Bell Miners on a Herbivorous Insect

Austral Ecology (2010) 35, 444–450 Non-lethal foraging by bell miners on a herbivorous insect: Potential implications for forest healthaec_2099 444..450 KATHRYN M. HAYTHORPE1,2 AND PAUL G. McDONALD2* 1School of Environmental and Life Sciences, Newcastle University, Newcastle, New South Wales, and 2Department of Brain, Behaviour and Evolution, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW 2109, Australia (Email: [email protected]) Abstract Tree health is often negatively linked with the localized abundance of parasitic invertebrates. One group, the sap-sucking psyllid insects (Homoptera: Psyllidae) are well known for their negative impact upon vegetation, an impact that often culminates in the defoliation and even death of hosts. In Australia, psyllid-infested forest in poor health is also frequently occupied by a native honeyeater, the bell miner (Manorina melanophrys; Meliphagidae), so much so that the phenomenon has been dubbed ‘bell miner-associated dieback’ (BMAD). Bell miners are thought to be the causative agent behind BMAD, in part because the species may selectively forage only upon the outer covering (lerp) exuded by psyllid nymphs, leaving the insect underneath to continue parasitizing hosts. As bell miners also aggressively exclude all other avian psyllid predators from occupied areas, these behavioural traits may favour increases in psyllid populations. We examined bell miner foraging behaviour to determine if non-lethal foraging upon psyllid nymphs occurred more often than in a congener, the noisy miner (M. melanocephala; Meliphagidae). This was indeed the case, with bell miners significantly more likely to remove only the lerp covering during feeding, leaving the insect intact underneath. This arose from bell miners using their tongue to pry off the lerp cases, whereas noisy miners used their mandibles to snap at both the lerp and insect underneath. -

Challenges in Managing Miners

Biodiversity symposium of south-east Queensland. Queensland Department of insect flower visitor diversity and feral honeybees on Forestry, Internal Report. jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata) in Kings Park, an Wylie FR and Peters BC (1987) Development of con- urban bushland remnant. Journal of the Royal Society tingency plans for use against exotic pests and dis- of Western Australia 88, 147-153. eases of trees and timber. 2. Problems with the detec- Yen AL (1995) Australian spiders: an opportunity for tion and identification of pest insect introductions conservation. Records of the Western Australian into Australia, with special reference to Queensland. Museum Supplement No. 52, 39-47. Australian Forestry 50, 16-23. Yen AL (2002) Short-range endemism and Australian Wylie FR and Yule RA (1977) Insect quarantine and Psylloidea (Insecta: Hemiptera) in the genera the timber industry in Queensland. Australian Glycaspis and Acizzia (Psyllidae). Invertebrate Forestry 40, 154-166. Systematics 16, 631-636. Wylie FR, De Baar M, King, J, Fitzgerald, C. and Yule RA and Watson JAL (1976) Three further domes- Peters BC (1996) Managing attack by bark and tic species of Cryptotermes from the Australian ambrosia beetles (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) in fire- mainland (Isoptera: Kalotermitidae). Journal of damaged Pinus plantations and salvaged logs in sout- Australian Entomological Society 15, 349-352. east Queensland. Paper Submitted to XX International Congress of Entomology, Firenze, Italy, August. 25-31. Received 18 January 2007; accepted 16 February 2007 Yates CJ, Hopper SD and Taplin RH (2005) Native Challenges in managing miners Michael F Clarke, Richard Taylor, Joanne Oldland, Merilyn J Grey and Amanda Dare Department of Zoology, La Trobe University, Bundoora, 3086 Corresponding author: M.Clarke Email: [email protected] Abstract Three of the four members of the genus Manorina have been linked to declines in bird diversity and abundance; they are the Noisy Miner M. -

BELL MINER ASSOCIATED DIEBACK in the BORDER RANGES NORTH and SOUTH BIODIVERSITY HOTSPOT - NSW SECTION

BMAD in the Border Ranges BELL MINER ASSOCIATED DIEBACK in the BORDER RANGES NORTH AND SOUTH BIODIVERSITY HOTSPOT - NSW SECTION. Dailan Pugh March 2018 This review focuses on the extent and effect of Bell Miner Associated Dieback (BMAD) on the NSW section of the Border Ranges (North and South), one of Australia's 15 Biodiversity Hotspots and part of one of the world's 35 Biodiversity Hotspots. The region's forests are recognised as being of World Heritage value. This review relies upon mapping of BMAD undertaken by the Forestry Corporation (DPI) in 2004 and the Forestry unit of the Department of Primary Industries (DPI) from 2015-17. The two DPI aerial visual sketch-mapping exercises were undertaken from a helicopter but map very different areas, which appears to be a methodological problem. To obtain a reasonable estimation both mappings were combined. Comparison with detailed mapping undertaken on the Richmond Range in 2005 shows that the recent mapping is only identifying 38% of the BMAD present, and that even when the two aerial visual sketch-mapping exercises are combined they still only identify 68% of BMAD, so while the DPI mapping has been relied upon herein as the only available regional mapping, the figures need to be considered very conservative. Conclusions from this review of the two DPI Bell Miner Associated Dieback mapping exercises undertaken in the NSW section of the Border Ranges Biodiversity Hotspot, and the 2017 Government literature review, are: • The most recent review confirms the basic process of initiating Bell Miner Associated Dieback (BMAD) as: logging opens up overstorey and disturbs understorey > invasion of lantana > proliferation of Bell Miners (Bellbirds) > proliferation of sap-sucking psyllids > sickening and death of eucalypts. -

The Responses of New Zealand's Arboreal Forest Birds to Invasive

The responses of New Zealand’s arboreal forest birds to invasive mammal control Nyree Fea A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington Te Whare Wānanga o te Ūpoko o te Ika a Māui 2018 ii This thesis was conducted under the supervision of Dr. Stephen Hartley (primary supervisor) School of Biological Sciences Victoria University of Wellington Wellington, New Zealand and Associate Professor Wayne Linklater (secondary supervisor) School of Biological Sciences Victoria University of Wellington Wellington, New Zealand iii iv Abstract Introduced mammalian predators are responsible for over half of contemporary extinctions and declines of birds. Endemic bird species on islands are particularly vulnerable to invasions of mammalian predators. The native bird species that remain in New Zealand forests continue to be threatened by predation from invasive mammals, with brushtail possums (Trichosurus vulpecula) ship rats (Rattus rattus) and stoats (Mustela erminea) identified as the primary agents responsible for their ongoing decline. Extensive efforts to suppress these pests across New Zealand’s forests have created “management experiments” with potential to provide insights into the ecological forces structuring forest bird communities. To understand the effects of invasive mammals on birds, I studied responses of New Zealand bird species at different temporal and spatial scales to different intensities of control and residual densities of mammals. In my first empirical chapter (Chapter 2), I present two meta-analyses of bird responses to invasive mammal control. I collate data from biodiversity projects across New Zealand where long-term monitoring of arboreal bird species was undertaken. -

Demographic Shifts in Noisy Miner (Manorina Melanocephala) Populations Following Removal

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine & Health - Honours Theses University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2017 Demographic shifts in Noisy Miner (Manorina melanocephala) populations following removal Jacob A T Vickers Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/thsci University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Vickers, Jacob A T, Demographic shifts in Noisy Miner (Manorina melanocephala) populations following removal, BEnviSc Hons, School of Earth & Environmental Science, University of Wollongong, 2017. -

National Recovery Plan for Helmeted Honeyeater (Lichenostomus

National Recovery Plan for the Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix Peter Menkhorst in conjunction with the Helmeted Honeyeater Recovery Team Compiled by Peter Menkhorst (Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria) in conjunction with the national Helmeted Honeyeater Recovery Team. Published by the Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) Melbourne, 2008. © State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2006 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne. ISBN 1 74152 351 6 This is a Recovery Plan prepared under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, with the assistance of funding provided by the Australian Government. This Recovery Plan has been developed with the involvement and cooperation of a range of stakeholders, but individual stakeholders have not necessarily committed to undertaking specific actions. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Proposed actions may be subject to modification over the life of the plan due to changes in knowledge. Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. An electronic version of this document is available on the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts website www.environment.gov.au For more information contact the DSE Customer Service Centre 136 186 Citation: Menkhorst, P. -

Birds of the Dungog Area (IOC Taxonomy) Compiled by Dick Jenkin, David Stuart and Bill Dowling on Behalf of Hunter Bird Observers Club

C = Common CS = Common Summer Migrant U = Uncommon US = Uncommon Summer Migrant R = Rare RS = Rare Summer Migrant RW = Rare Winter Migrant Birds of the Dungog Area (IOC Taxonomy) Compiled by Dick Jenkin, David Stuart and Bill Dowling on behalf of Hunter Bird Observers Club Australian Brush-turkey C Intermediate Egret U Rainbow Lorikeet C Stubble Quail U Cattle Egret C Scaly-breasted Lorikeet R Brown Quail C White-faced Heron C Musk Lorikeet R King Quail R Little Egret R Little Lorikeet R Wandering Whistling- R Nankeen Night-Heron R Australian King-Parrot C Duck Australian White Ibis C Crimson Rosella C Musk Duck R Straw-necked Ibis C Eastern Rosella C Black Swan U Royal Spoonbill C Swift Parrot R Australian Wood Duck C Yellow-billed Spoonbill U W Australasian Shoveler R Black-shouldered Kite C Red-rumped Parrot U Grey Teal C Pacific Baza U Pheasant Coucal C Chestnut Teal R White-bellied Sea-Eagle U Eastern Koel CS Pacific Black Duck C Whistling Kite U Channel-billed Cuckoo CS Hardhead U Black Kite R Horsfield’s Bronze- R Cuckoo Australasian Grebe C Brown Goshawk C Shining Bronze-Cuckoo U Hoary-headed Grebe R Collared Sparrowhawk U Fan-tailed Cuckoo C Rock Dove U Grey Goshawk U Brush Cuckoo US White-headed Pigeon C Spotted Harrier R Pallid Cuckoo US Spotted Dove C Wedge-tailed Eagle C Powerful Owl U Brown Cuckoo-Dove C Little Eagle R Southern Boobook C Emerald Dove U Nankeen Kestrel C Sooty Owl R Crested Pigeon C Brown Falcon C Masked Owl R Peaceful Dove R Australian Hobby C Barn Owl C Bar-shouldered Dove C Peregrine Falcon R Azure Kingfisher -

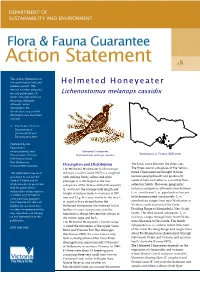

Helmeted Honeyeater Version Has Been Prepared for Web Publication

#8 This Action Statement was first published in 1992 and remains current. This Helmeted Honeyeater version has been prepared for web publication. It Lichenostomus melanops cassidix retains the original text of the action statement, although contact information, the distribution map and the illustration may have been updated. © The State of Victoria, Department of Sustainability and Environment, 2003 Published by the Department of Sustainability and Helmeted Honeyeater Environment, Victoria. (Lichenostomus melanops cassidix) Distribution in Victoria (DSE 2002) 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne, The birds move between the three sites. Victoria 3002 Australia Description and Distribution The Helmeted Honeyeater (Lichenostomus The three coastal subspecies of the Yellow- This publication may be of melanops cassidix Gould 1867) is a songbird tufted Honeyeater are thought to have assistance to you but the with striking black, yellow and olive become geographically and genetically State of Victoria and its plumage. It is the largest of the four isolated from each other as a result of their employees do not guarantee subspecies of the Yellow-tufted Honeyeater sedentary habits. However, geographic that the publication is (L. melanops): the average total length and isolation and genetic differentiation between without flaw of any kind or weight of mature males is in excess of 200 L. m. cassidix and L. m. gippslandicus has yet is wholly appropriate for to be demonstrated conclusively. L. m. your particular purposes mm and 32 g. It is very similar to the race L. gippslandicus ranges from near Warburton in and therefore disclaims all m. gippslandicus, except that in the liability for any error, loss Helmeted Honeyeater the forehead tuft of Victoria, south and east of the Great or other consequence which feathers is more conspicuous and the Dividing Range to Merrimbula, New South may arise from you relying transition is abrupt between the colours of Wales. -

Download the Bird Trail

21/12/10 10:03 AM 10:03 21/12/10 1 ka1479_A3DL_ART2.indd Lithgow Visitor Information Centre Oberon Visitor Information Centre Cnr Ross Street & Edith Road, Oberon Blue Mountains Heritage Centre, Great Western Highway, Glenbrook, Magpies, Honeyeaters, Treecreepers and Fantails. and Treecreepers Honeyeaters, Magpies, Great Western Highway, Lithgow Thornbills, Silvereyes, Scrubwrens, Parrots, Parrots, Scrubwrens, Silvereyes, Thornbills, End of Govetts Leap Raod watering places. These tolerant species include include species tolerant These places. watering visitbluemountains.com.au you are standing quietly near their feeding and and feeding their near quietly standing are you Information Centres: Phone: (02) 4787 8877 Phone: (02) 6329 8210 Echo Point, Katoomba Phone: 1300 760 276 if away, metres few a only from them watch Phone: 1300 653 408 Phone: 1300 653 408 Blue Mountains to you for happy are species bird our of Many National Parks sometimes run ahead of you. of ahead run sometimes along the walking tracks the Bassian Thrush will will Thrush Bassian the tracks walking the along the Eastern Yellow Robin. If you walk slowly slowly walk you If Robin. Yellow Eastern the Shrike-thrush, the Rockwarbler (Origma) and and (Origma) Rockwarbler the Shrike-thrush, few of our most inquisitive species are the Grey Grey the are species inquisitive most our of few O’Connell (from Oberon 238km) (Abercrombie Road Tablelands Wa and Canberra vi To Taralga, Goulburn Bathurs A you. at look and come may birds our of t some view the admiring or rest a picnic, a Call in at any one of our Accredited Visitor Information Centres for advice and assistance from trained local staff. -

BIRD LIST NEW ZEALAND South Island – (31

AROUND THE WORLD – BIRD LIST NEW ZEALAND South Island – (31) North Island – (10) Yellow-eyed penguin North Island robin Blue penguin Saddleback White-faced heron Stitchbird (hihi) Black swan Eastern rosella South Island pied oystercatcher Banded rail Variable oystercatcher Pied shag New Zealand pigeon Welcome swallow Bellbird Banded dotterel Tui New Zealand pipit Australian magpie Paradise shelduck Tomtit Silvereye Blackbird Song thrush Chaffinch Yellow hammer Royal spoonbill New Zealand falcon New Zealand fantail Red-billed gull Black-backed gull Gray warbler Bar-tailed godwit Pied stilt Goldfinch Black shag Black-billed gull Spur-winged plover (masked lapwing) California quail Pukeko Common mynah Cook Strait Ferry – (5) Spotted shag Westland petrel Gannet Fluttering shearwater Buller’s albatross AUSTRALIA Queensland (QLD) – (33) Tasmania (TAS) – (11) Whimbrel Superb fairywren Willie wagtail Tasmanian nativehen (turbo chook) Magpie-lark Dusky moorhen White-breasted wood swallow Green rosella Red-tailed black cockatoo Yellow wattlebird (endemic) Sulphur-crested cockatoo Hooded dotterel (plover) Figbird Galah Rainbow lorikeet Crescent honeyeater Pied (Torresian) imperial pigeon Great cormorant Australian pelican Swamp harrier Greater sand plover Forest raven Pectoral sandpiper Peaceful dove Victoria (VIC) – (10) Australian brush-turkey Emu Australian (Torresian) crow Gray fantail Common noddy Pacific black duck Brown booby King parrot Australian white ibis Australian wood duck Straw-necked ibis Red wattlebird Magpie goose Bell miner Bridled -

Dare MU07014.Qxd

CSIRO PUBLISHING www.publish.csiro.au/journals/emu Emu, 2008, 108, 175–180 The social and behavioural dynamics of colony expansion in the Bell Miner (Manorina melanophrys) Amanda J. Dare A,C, Paul G. McDonald B and Michael F. Clarke A ADepartment of Zoology, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Vic. 3086, Australia. BCentre for the Integrative Study of Animal Behaviour, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW 2109, Australia. CCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Bell Miners (Manorina melanophrys) are cooperatively breeding honeyeaters that defend colonies from potential predators and competitors. Despite extensive study of the social organisation of Bell Miners, little is known about the social dynamics of expansion of colonies and establishment of new territories in this species. We took advantage of an individually marked, molecularly sexed and genotyped study population to examine the social dynamics of two extensions of the range of a colony. These observations indicated colonisation of new areas by colony members was accomplished via two different pathways, either the efforts of a breeding pair and its pre-existing contingent of helpers, or a group of unmated males. Only the former bred, with greater numbers of individuals related to the breeding pair acting as helpers in new areas initially. Most colonists were males that lacked a breeding position. Ultimately both expansions of the colony proved to be temporary, with colonists returning to their former home-ranges after six months. Introduction Although colonies of Bell Miners (Manorina melanophrys) are (Clarke 1989). Breeding males, but not females, also assist and known to appear and disappear from sites (McCulloch and provision broods of other coterie members, even while actively Noelker 1974), little is known about how this highly territorial involved in raising their own broods.