Trafficking in Persons Report June 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DAY MY GOD DIED RELEASE.Qk

NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Cara White 843/881-1480 [email protected] Mary Lugo 770/623-8190 [email protected] Randall Cole 415/356-8383 x254 [email protected] Wilson Ling 415/356-8383 x231 [email protected] Pressroom for more information and/or downloadable images: www.itvs.org/pressroom/photos Program companion website: www.pbs.org/daymygoddied INDEPENDENT LENS’s “THE DAY MY GOD DIED” EXAMINES GROWING PLAGUE OF CHILD SEX SLAVERY Heart-wrenching Expose Takes Viewers inside the Horrific World of Sex Trafficking and Introduces Audience to Young Women who Survived the Brothels of Bombay and Have Dedicated Their Lives to Ending this Widespread Epidemic Film by Andrew Levine Narrated by Tim Robbins Airs Nationally on “Independent Lens” THE DAY MY GOD DIED Emmy® Award-Winning Series on PBS Hosted by Susan Sarandon Tuesday, November 30, 2004 at 10:00 P.M. (check local listings) (San Francisco, CA) — According to the United Nations, 2,500 women and children throughout the world disappear every day to be sold into sexual slavery. Many of these are young Nepalese girls who are trafficked, often by someone they trust, and sold into sexual servitude in Bombay’s night- marish red-light district Kamthipura—a filthy, teeming, sexual marketplace of over 200,000 young women and children known as “the cages.” Sexual servitude is also often times a death sentence. In Bombay alone, 90 new cases of HIV infection are reported every hour. These victims are getting younger—two decades ago, most women in the Indian brothels were in their twenties or thirties, but today, the average age is 14. -

IJM 2015 Mid Year Report

international justice mission 2015 Mid Year Report ambushed and afraid Benedeta’s Story PAGE 13 OUR VISION Rescue thousands. Protect millions. Prove that justice for the poor is possible. 2 INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE MISSION ABOUT IJM We are International Justice Mission. Our global team has spent nearly 20 years on the front lines fighting some of the worst forms of violence in Africa, Latin America, South Asia and Southeast Asia. We partner with local authorities to: RESCUE VICTIMS BRING CRIMINALS RESTORE STRENGTHEN OF VIOLENCE TO JUSTICE SURVIVORS JUSTICE SYSTEMS We help local We work relentlessly We provide authorities find in local courts to trauma therapy We identify gaps individuals and ensure traffickers, and counseling to in the systems that families suffering slave owners, rapists survivors of violence protect the poor, and from violence and and other criminals and give survivors then work with police oppression and bring are restrained from education, training and courts to address them to safety. hurting others. and tools to thrive. these challenges. OUR PROGRESS THIS YEAR 2,038 4,374 177 15,000+ Victims of Survivors and Perpetrators of Justice system oppression their family violent crimes officials and rescued by IJM members restrained community and IJM-trained receiving members trained partners aftercare Numbers reflect January—May 2015. 2015 MID-YEAR REPORT 3 IMPACT Our Global ijm Canada Impact ijm headquarters Today, we are helping to protect more than 21 million people from violence in nearly 20 communities throughout the developing world. guatemala city, IJM Headquarters is located in guatemala Washington, DC, and we have part- ner offices in Australia, Canada, UK, the Netherlands and Germany. -

Fighting to End Slavery. for Good

international justice mission FIGHTING TO END SLAVERY. FOR GOOD. UNTIL ALL ARE FREE UNTIL ALL ARE FREE 1 TODAY, 35 million CHILDREN, WOMEN AND MEN ARE HELD AS SLAVES. 2 INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE MISSION OUR MODEL In the developing world, violence is as much a part We believe when laws are enforced by well-trained of daily life as hunger, disease or homelessness—but and equipped police and courts, people are better it’s often overlooked. This allows crimes like slavery protected from slave owners, traffickers and and sex trafficking to thrive. other abusers. Children and families are vulnerable because their For nearly twenty years, IJM has been standing justice systems don’t protect them. on the front lines, together with our local partners and a global justice movement, to push back the Established laws are rarely enforced, so criminals advance of everyday violence and bring an end continue to rape, enslave, traffic and abuse them to slavery—for good. IJM works through 17 field without the fear of the law being enforced. offices throughout Africa, Latin America, South and Southeast Asia. IJM is headquartered in the U.S. and IJM is a global organization that protects the has partner offices around the globe located in the poor from violence in the developing world. UK, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands and Australia. IJM: HELPING TO PROTECT MORE THAN 21 MILLION PEOPLE FROM VIOLENCE WORLDWIDE. IJM’S MODEL: HELP VICTIMS AND REPAIR JUSTICE SYSTEMS SO THEY FUNCTION FOR EVERYONE. RESCUE RESTORE Work with local police to Provide counseling, education -

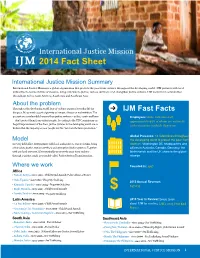

2014 Fact Sheet

International Justice Mission 2014 Fact Sheet International Justice Mission Summary International Justice Mission is a global organization that protects the poor from violence throughout the developing world. IJM partners with local authorities to rescue victims of violence, bring criminals to justice, restore survivors, and strengthen justice systems. IJM works in 18 communities throughout Africa, Latin America, South Asia and Southeast Asia. About the problem Throughout the developing world, fear of violence is part of everyday life for the poor. It’s as much a part of poverty as hunger, disease or malnutrition. The → IJM Fast Facts poorest are so vulnerable because their justice systems – police, courts and laws Employees: 600+ full-time staff, – don’t protect them from violent people. According to the UN Commission on approximately 95% of whom are nationals Legal Empowerment of the Poor, justice systems in the developing world are so of the countries in which they serve broken that the majority of poor people live life “far from the law’s protection.” Global Presence: 18 field offices throughout Model the developing world to protect the poor from In every field office, IJM partners with local authorities to rescue victims, bring violence. Washington DC headquarters and criminals to justice, restore survivors and strengthen justice systems. Together offices in Australia, Canada, Germany, the with our local partners, IJM sustainably protects the poor from violence Netherlands and the UK share in the global through a unique, multi-year -

Empowering Justice Systems to Decimate Modern Slavery at Its Source

Human Trafficking Institute Empowering justice systems to decimate modern slavery at its source Chief Executive Officer ICTOR BOUTROS is the CEO and co-founder of the Human Trafficking Institute and co-author Vwith Gary Haugen of The Locust Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the End of Violence, a book published by Oxford University Press in 2014. Drawing on real-world cases and extensive scholarship, The Locust Effect paints a vivid portrait of the way fractured criminal justice systems in developing countries have spawned a hidden epidemic of human trafficking and everyday violence that is undermining vital investments in poverty alleviation, public health, and human rights. The Locust Effect is a Washington Post bestseller that has been featured by the New York Times, The Economist, NPR, the Today Show, Forbes, TED, and the BBC, among others. For their work on The Locust Effect, Boutros and Haugen received the 2016 Grawemeyer Prize for Ideas Improving World Order, a prize awarded annually to the authors of one book based on originality, feasibility, and potential for global impact. Boutros previously served as a federal prosecutor on human trafficking cases of national significance on behalf of the United States Department of Justice’s Human Trafficking Prosecution Unit. He has taught human trafficking at the FBI Academy in Quantico, trained law enforcement professionals in the United States and other countries on how to investigate and prosecute human trafficking, and taught trial advocacy to lawyers from Latin America, South and Southeast Asia, and Africa. Boutros is a graduate of Baylor University, Harvard University, Oxford University, and the University of Chicago Law School, where he was as an editor of the University of Chicago Law Review. -

Viewing My Manuscript

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 In Search of an Attentive Public and Involvement in the Anti-Trafficking Movement Ashley Russell Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE IN SEARCH OF AN ATTENTIVE PUBLIC AND INVOLVEMENT IN THE ANTI-TRAFFICKING MOVEMENT By ASHLEY RUSSELL A Dissertation submitted to the College of Criminology and Criminal Justice in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 2017 © 2017 Ashley Russell Ashley Russell defended this dissertation on July 5, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Marc G. Gertz Professor Directing Dissertation Martin Kavka University Representative Carter Hay Committee Member Sonja E. Siennick Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii In loving memory of William and Sara Russell Dedicated to my parents, my Sherpas, David and Lois Russell iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I walked onto the campus of Florida State University as a freshman at 18 years old and I’ve spent the past decade in the College of Criminology. It takes a village to raise a child, and there are many people to thank for raising me. Dr. Gertz is the reason I came back the Ph.D. program after graduation. Thank you for seeing something in me that I did not see in myself. I believe my life and my career will be significantly better because of this experience and it would not have happened without you. -

Chapter Trafficking and the “Victim Industry” Complex

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Trafficking and the “Victim Industry” Complex Book Section How to cite: Bouklis, Paraskevi S. (2016). Trafficking and the “Victim Industry” Complex. In: Antonopoulos, Georgios A. ed. Illegal Entrepreneurship, Organized Crime and Social Control Essays in Honor of Professor Dick Hobbs. Studies of Organized Crime (14). Springer, pp. 237–263. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2016 Avi Boukli https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31608-614 http://www.springer.com/gb/book/9783319316062 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Chapter Trafficking and the “Victim Industry” Complex Paraskevi S. Bouklis1 Abstract The antithesis between a criminalization and a human rights approach in the context of transnational trafficking in women has been a highly contested issue. On the one hand, it is argued that a criminalization approach would be better because security and border control measures will be fortified. On the other hand, it is maintained that a human rights approach would bring more effective results, as this will mobilize a more holistic solution, bringing together prevention, prosecution, protection of victims and partnerships for delivering gendered victims’ services. In the field of victims’ services, galloping US-influenced developments have mobilized victim- specific strategies and institutionalized a “victim industry” vocabulary: “reflection period”, “screening process”, “cooperation in exchange for protection”, “happy trafficking”, “renew boutique” etc. -

Year-End Report at a Glance in 2013

INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE MISSION 2013 Year-End Report At a Glance in 2013 IJM and IJM-trained partners Relieved more than 3,400 victims of oppression our highest annual total ever. Restrained more than 300 violent criminals securing more convictions and arrests than ever before. Launched 2 new field offices (In Delhi & Dominican Republic) for a total of 18 field offices. Launched 3 new demonstration projects for a total of 8 offices that have an intensive focus on reforming their justice systems. COVER: Zambia—This year, IJM helped restore Grace’s rights to her home after it was stolen by stronger members of her community. Now, she can provide a stronger future for her grandchildren. IJM’s Vision: Rescue thousands. Protect millions. Prove that justice for the poor is possible. A Message from support to ensure their courts and law enforcement were IJM President Gary Haugen serving the poor. These are the kinds of changes that will make the most vulnerable people safe from violence far This year, we saw the beauty of individual lives transformed beyond our direct assistance. These are the kinds of and hope restored. A trafficking survivor courageously led changes that will impact history. a rescue operation to free other victims. A young woman who was once a slave proudly enrolled in nursing school. We invite you to rejoice with us, because these miracles A widow returned to the home that had been stolen from of change are possible simply through the faithful her with joy that was so uncontainable, she led our team partnership of friends who believe that justice for the poor in dancing. -

Grace Farms Foundation Launches Justice Initiative to Activate and Synergize Private and Public Sector to Disrupt and Help Eradicate Child Exploitation

Media Contacts Polskin Arts & Communications Counselors: Connecticut: Jennifer Essen Katherine Slovik Gwen North Reiss [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 212.593.5881 212.715.1594 203.966.6530 GRACE FARMS FOUNDATION LAUNCHES JUSTICE INITIATIVE TO ACTIVATE AND SYNERGIZE PRIVATE AND PUBLIC SECTOR TO DISRUPT AND HELP ERADICATE CHILD EXPLOITATION Inaugural Two-Day Workshop to be Held at Grace Farms November 5-6 Grace Farms, the River building, Library, Justice Initiative Panel led by Krisha Patel, Director of Justice Initiatives at Grace Farms; © Dean Kaufman NEW CANAAN, CT — Advancing its work in a core program area, Grace Farms Foundation today announced that it will inaugurate its Justice Initiative by organizing a two-day workshop to create synergies across the private and public sector and to activate community groups to develop comprehensive long-term strategies and part- nerships to combat child sex trafficking and gender-based violence. Convening on November 5 and 6, 2015 from 8:30 am to 6:30 pm, the workshop will address the three key areas of the Foundation’s Justice Initiative to create a multi-disciplinary model focused on disrupting and eradicating child exploitation: awareness and prevention, investigation and prosecution, and victim services. Over the two-day period, the workshop will progress from discussing the issue on an international, to national and then local level. Open to the public, the workshop will be held at Grace Farms, the new center for nature, arts, community, justice and faith in New Canaan, Connecticut. The workshop is organized by Sharon Prince, President of Grace Farms Foundation; Krishna R. -

2020 Annual Report | Together We Are Feeding America

TOGETHER W E ARE FEEDING AMERICA PG 1 ANNUAL REPORT 20 20 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2020 ANNUAL REPORT MOTIVATION MISSION IMPACT 3 5 9 FINANCIALS 27 SUPPORTERS 30 LEADERSHIP 67 PG 2 MOTIVATION 2020 ANNUAL REPORT MEET ELENA On a hot summer morning, Elena Martinez, along with her sons—Kevin, 4 and Adonay, 2—arrived at a food pantry that works with Capital Area Food Bank, a member of the Feeding America network. Before the impact of COVID-19, Elena worked in a restaurant kitchen. Due to the economic fallout from the pandemic, she— like tens of millions of people across the country—lost her job. As Elena saw the nutritious food available for her to take home to help feed her family of seven, she smiled, excited about the meals she could prepare amid a devastating time of unemployment and uncertainty. Women like Elena are overrepresented in some of the hardest-hit industries for job loss, including leisure and hospitality, healthcare and education, and women—especially “ Black and Latino women—lost jobs in those sectors I’M VERY at disproportionate rates. GRATEFUL TO GOD THAT MY FAMILY IS ABLE TO EAT BECAUSE OF THE FOOD THAT I RECEIVE FROM THE PANTRY. ” PG 3 MOTIVATION 2020 ANNUAL REPORT MEET OUR VOLUNTEERS Before the pandemic, the Feeding America food bank network relied on the generous time of nearly 2 million volunteers each month. The impact of COVID-19 quickly shattered that. Adhering to shelter- in-place orders, social-distancing protocols and health concerns, food banks saw a 60% decline in this critical volunteer workforce. -

Running from the Rescuers: New U.S. Crusades Against Sex Trafficking and the Rhetoric of Abolition

Running from the Rescuers: New U.S. Crusades Against Sex Trafficking and the Rhetoric of Abolition GRETCHEN SODERLUND This article analyzes recent developments in U.S. anti-sex trafficking rhetoric and practices. In particular, it traces how pre-9/11 abolitionist legal frameworks have been redeployed in the context of regime change from the Clinton to Bush administrations. In the current political con- text, combating the traffic in women has become a common denominator political issue, uniting people across the political and religious spectrum against a seemingly indisputable act of oppression and exploitation. However, this essay argues that feminists should be the ! rst to inter- rogate and critique the premises underlying many claims about global sex trafficking, as well as recent U.S.-based efforts to rescue prostitutes. It places the current raid-and-rehabilitation method of curbing sex traf- ! cking within the broader context of Bush administration and conser- vative religious approaches to dealing with gender and sexuality on the international scene. Keywords: sex trafficking / social movements / prostitution / journalism / violence against women / evangelism “Our job under this statute is to end trafficking. If America fails to take the lead in rescuing the victims, there’s no other nation that will.” —John R. Miller, Director of the State Department’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (quoted in Morse 2003) “[Sex trafficking] just jumped off the pages of the newspaper.” —Richard Cizik, National Association of Evangelicals (quoted in Shapiro 2004) Two years ago an undercover team comprised of an MSNBC Dateline producer and a sex-trafficking investigator scouted the streets of Phnom Penh, Cambodia, for evidence of child prostitution. -

Annual Report

INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE MISSION 2013 Annual Report Yulisa* and her family—read their story on page 13 1 Message from IJM President & CEO Gary Haugen In 2013, we witnessed progress that would have their courts and law enforcement are serving the poor. been unimaginable just a few years ago. We rescued These are the kinds of changes that will make the most more people than ever before. We restrained violent vulnerable people safe from violence far beyond our criminals who once ruled with utter impunity in their direct assistance. These are the kinds of changes that will communities, securing more convictions and arrests impact history. than ever before. In every IJM field office around the world, there is a sense My colleagues in the field have painstakingly built of momentum. And we are ready to take hold of it—to see Our Vision relationships of trust, relentlessly provided support, and even more history made in 2014. We invite you to rejoice partnered with local authorities on case after case. Even with us, because these miracles of change are possible when they have faced opposition, obstacles and disbelief simply through the faithful partnership of friends who that anything can actually change for the poor, they have stand with us to protect the poor from violence. Rescue thousands. persevered. And as we witness lives change, together we have shown that the system can work—and that justice for the poor is possible. Joyfully, Protect millions. This was a year of dramatic progress in that urgent work. In places where we were once met with apathy and broken systems, local governments are now not only Prove that justice for willing to work with us, but are responding proactively to violence against the poorest—from initiating cases Gary A.