Epub Institutional Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using TRIZ to Enhance Passengers' Perceptions of an Airline's Image Through Service Quality and Safety

Journal of Air Transport Management 53 (2016) 131e139 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Air Transport Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jairtraman Using TRIZ to enhance passengers' perceptions of an airline's image through service quality and safety * Thongchai Jeeradist a, Natcha Thawesaengskulthai b, , Thanawan Sangsuwan c a Technopreneurship and Innovation Management, Graduate School, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand b Department of Industrial Engineering Faculty of Engineering, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand c Department of Marketing, Faculty of Commerce and Accountancy, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand article info abstract Article history: To improve the impacts of airline image, service quality and safety on passenger perceptions, this paper Received 29 April 2015 examined and presented three case studies to identify the factors that influenced service quality in the Received in revised form airline business, and passenger perceptions of airline image. A literature review on service quality 11 February 2016 measurement (SQM) and airline safety analysed case studies. The quality management framework Accepted 13 February 2016 SERVQUAL with five service quality dimensions including reliability, assurance, tangibility, empathy and Available online xxx responsiveness was used to assess passenger requirements. Selected criteria from airline services and the Kano model measured customer satisfaction. Airline safety criteria were studied and TRIZ techniques Keywords: -

Comparison of World Airline Rankings with Different Criteria: Best Airline Ranking and EVAMIX Method Rank

American Research Journal of Humanities Social Science (ARJHSS)R) 2019 American Research Journal of Humanities Social Science (ARJHSS) E-ISSN: 2378-702X Volume-02, Issue-03, pp-38-46 March-2019 www.arjhss.com Research Paper Open Access Comparison of World Airline Rankings with Different Criteria: Best Airline Ranking and EVAMIX Method Rank Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ozlem Deniz Basar, Istanbul Commerce UniversityDepartment of Statistics Sutluce Mah., Imrahor Cad., No :90, Beyoglu / Istanbul / Turkey Phone : +90-212-444-0413/4613 ABSTRACT:- Competition in the transportation sector is in constant rise as in all sectors today. It is crucial for airlines, which are one of the most important shareholders in the transportation sector, to be recognized and reliable in order to have a place in the market. For this reason, different companies prepare and share a world airline ranking with public each year. These rankings are prepared using different criteria and methodologies. Hence, each of these rankings differs from each other. This study considers the Best Airline Ranking prepared by Airhelp in 2018. The first 15 airlines in this ranking are re-ranked with the EVAMIX method using unused criteria and the results are compared with the Best Airline Ranking. In the conclusion of the study, it is found out that rankings changed significantly; hence, it is greatly important to determine what is desired to measure when the airlines are compared. Keywords: Airline, Ranking, EVAMIX, Critic Method I. INTRODUCTION It is of importance to meet the changing consumer demands, reach and serve more customers in the aviation sector as in all other sectors. -

DHL and Leipzig Now Lead ATM Stats 3 European Airline Operations in April According to Eurocontrol

Issue 56 Monday 20 April 2020 www.anker-report.com Contents C-19 wipes out 95% of April air traffic; 1 C-19 wipes out 95% of April air traffic; DHL and Leipzig now lead movements statistics in Europe. DHL and Leipzig now lead ATM stats 3 European airline operations in April according to Eurocontrol. The coronavirus pandemic has managed in the space of a According to the airline’s website, Avinor has temporarily month to reduce European air passenger travel from roughly its closed nine Norwegian airports to commercial traffic and 4 Alitalia rescued (yet again) by Italian normal level (at the beginning of March) to being virtually non- Widerøe has identified alternatives for all of them, with bus government; most international existent (at the end of March). Aircraft movement figures from transport provided to get the passengers to their required routes from Rome face intense Eurocontrol show the rapid decrease in operations during the destination. competition; dominant at Milan LIN. month. By the end of the month, flights were down around Ryanair still connecting Ireland and the UK 5 Round-up of over 300 new routes 90%, but many of those still operating were either pure cargo flights (from the likes of DHL and FedEx), or all-cargo flights Ryanair’s current operating network comprises 13 routes from from over 60 airlines that were being operated by scheduled airlines. Ireland, eight of which are to the UK (from Dublin to supposed to have launched during Birmingham, Bristol, Edinburgh, Glasgow, London LGW, London the last five weeks involving Leipzig/Halle is now Europe’s busiest airport STN and Manchester as well as Cork to London STN). -

Loganair to Significantly Enhance Connectivity Between Brussels And

Press release Loganair to significantly enhance connectivity between Brussels and Aberdeen Loganair has announced today (9th September) that it is to offer a new and enhanced routing between between Brussels and Aberdeen, shortening journey times to just over 3 hours. The airline has optimised its schedule to enable customers in Brussels to travel to the Scottish oil and gas hub, via its direct route to Newcastle (which commenced earlier this year). Compared to current connecting options elsewhere, that are currently more than 5 hours in length, the new connectivity is a significant enhancement for travellers doing business between Brussels and Europe’s Oil Capital. The Scottish airline is set to commence a year-round, four day per week business return schedule on 28 October, operating Monday to Thursday - connecting the two cities during the working week. Operated by a 37-seat Embraer 135 jet aircraft with a flight time of only three hours and 15 minutes, the service will have a brief stopover at Newcastle Airport during which customers can clear customs. Loganair commenced operations from Brussels Airport in February, taking over air services to Newcastle from flybmi. Two weeks ago it also launched its second route from Brussels, connecting the city to the UK’s East Midlands Airport. Aberdeen is Scotland’s third largest city and is surrounded by stunning coastline and beautiful countryside which includes the majestic, Cairngorms National Park, world-famous Dunnottar Castle and the Speyside whisky region. The airline has also been growing its presence at Aberdeen Airport, establishing itself as the North-East airport’s largest operator both by number of flights and destinations served. -

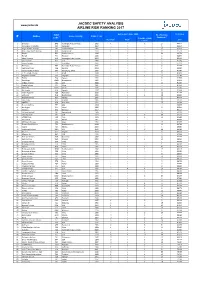

2017 JACDEC AIRLINE SAFETY RANKING-ENG.Xlsx

JACDEC SAFETY ANALYSIS www.jacdec.de AIRLINE RISK RANKING 2017 2 ICAO Hull Losses since 1988 No of Serious Risk Index Airline Home Country Begin of Ops # 1 Incidents 2 Code Total No of Hull Non-fatal 3 Fatal 3 2017 Losses 2 1 Emirates UAE Vereinigte Arab. Emirate 1985 1 0 1 27 93,61% 2 Norwegian Air Shuttle NAX Norwegen 1993 0 0 0 6 93,26% 3 Virgin Atlantic Airways VIR Großbritannien 1984 0 0 0 15 92,87% 4 KLM - Royal Dutch Airlines KLM Niederlande 1920 1 0 1 21 92,77% 5 EasyJet EZY Großbritannien 1996 0 0 0 24 92,75% 6 Finnair FIN Finnland 1923 0 0 0 5 92,67% 7 Etihad Airways ETD Vereinigte Arab. Emirate 2003 0 0 0 10 92,56% 8 Spirit Airlines NKS USA 1980 0 0 0 5 92,18% 9 Jetstar Airways JST Australien 2004 0 0 0 9 92,12% 10 Air Arabia ABY Vereinigte Arab. Emirate 2003 0 0 0 2 92,09% 11 Vueling Airlines VLG Spanien 2004 0 0 0 8 92,02% 12 Cathay Pacific Airways CPA Hong Kong, China 1946 0 0 0 10 91,88% 13 EL AL - Israel Airlines ELY Israel 1949 0 0 0 11 91,84% 14 Singapore Airlines SIA Singapur 1972 0 1 1 20 91,78% 15 EVA Air EVA Taiwan 1991 0 0 0 6 91,55% 16 Eurowings EWG Deutschland 1993 0 0 0 8 91,41% 17 jetBlue Airways JBU USA 2000 0 0 0 11 91,40% 18 Capital Airlines CBJ China 1995 0 0 0 0 91,36% 19 Oman Air OMA Oman 1981 0 0 0 2 91,28% 20 Air Canada ACA Kanada 1937 2 0 2 32 91,20% 21 Virgin Australia VOZ Australien 2000 0 0 0 12 91,15% 22 Lufthansa DLH Deutschland 1955 0 1 1 39 90,92% 23 WestJet Airlines WJA Kanada 1996 0 0 0 13 90,91% 24 Air Europa AEA Spanien 1986 0 0 0 11 90,76% 25 QANTAS QFA Australien 1922 0 0 0 25 90,39% 26 -

2013-10-17-Jacdec Analysis Atr + Dhc84

JACDEC ANALYSIS DHC-8-400 versus ATR-72 JACDEC ANALYSIS 17 OCT 2013 JACDEC ANALYSIS - Quick Datasheet A Safety Comparison between Bombardier DHC-8-400 and ATR-72 Over a period of 15 years (1999 - 2013) Bombardier DHC-8-400 "Dash 8" ATR-72 Role: Regional Turboprop Aircraft Regional Turboprop Aircraft Seat Capacity: 68 - 80 Passengers 68 - 74 Passengers Powerplant: 2x Pratt & Whitney Canada PW150A Turboprop 2x Pratt & Whitney Canada PW127 Turboprop Entry of commercial service: Summer 1999 Q4 1989 (Finnair) Number built (as of OCT 01 2013): 448 651 Number of Hull Losses: 6 15 Number of Serious Incidents: 19 35 Number of on board fatalities: 49 169 Number of on board injured: 17 89 Hull Losses per year (´99 - 2013): 0,40 1,00 Fatalities per year (´99 - 2013): 3,27 11,27 Hull Losses by Airframes (´99 -2013): 0,01 1,36 % 0,02 2,21 % Hull Losses by Region Africa Asia / Pacific 2 33,33 % 6 40,00 % Eurasia 1 16,67 % 1 6,67 % Europe 1 16,67 % 3 20,00 % Latin America 2 13,33 % Mid-East Asia 3 20,00 % North America 2 33,33 % International Territory: © JACDEC Database JACDEC ANALYSIS DHC-8-400 versus ATR-72 JACDEC ANALYSIS SAFETY COMPARISON DHC-8-400 vs. ATR-72 HULL LOSS ACCIDENT DISTRIBUTION MAP 2 = DHC-8-400 accident country = ATR-72 accident country Canada 1x Bangladesh 1x China 1x Cuba 1x Denmark 1x India 2x Lithuania 1x Italy 2x South Korea 1x Laos 1x USA 1x Myanmar 2x Philippines 1x Puerto Rico 1x Poland 1x Russia 1x Taiwan 1x Thailand 1x CURRENT OPERATOR LIST DHC-8-400 ATR-72 Operators Fleet Size Operators Fleet Size Alaska Horizon 48 Azul Linhas Aéreas Brasileiras 26 FlyBE 43 Wings Abadi Air 24 Republic AL 30 TRIP Linhas Aéreas 19 Sunstate AL / QantasLink 30 Jet AW 17 Porter AL 26 UTair Avn 15 Jazz Air 21 FedEx 15 ANA Wings 21 Executive AL / American Eagle 14 SpiceJet 15 Mount Cook AL 14 Austrian 14 Firefly 13 Air Baltic 12 Virgin Australia Regional AL 13 Japan Air Commuter 11 Vietnam AL 12 Wideroe 10 FlyBE Finland 12 Pantheon AW 10 Farnair Switzerland 12 LGW Luftfahrtges. -

Travel Weekly Insight Annual Report 2019-2020

Produced in association with Front Cover VERSION REPRO OP REPRO SUBS Annual Report 2019-20 ART PRODUCTION CLIENT Forty-seven million reasons to be confident in 2020 Produced by Travel Weekly, with exclusive consumer research BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 91TRS1951903.pgs 02.12.2019 08:46 Deloitte VERSION REPRO OP REPRO SUBS ART PRODUCTION CLIENT Be ahead of the changing consumer www.deloitte.co.uk/ths JJ1904619046 TTravelravel WWeeklyeekly AAmendsmends 2270mmx203mm70mmx203mm iir.inddr indd 1 002/12/20192/12/2019 009:419:41 BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 91TRS1951900.pgs 02.12.2019 11:36 Contents VERSION Contents TRAVEL WEEKLY INSIGHT REPORT 2019-20 REPRO OP REPRO 4 Executive summary 18 Inbound 32 Hospitality SUBS 5 Key findings 20 Domestic 35 Travel technology 7 Consumer research 22 Cruise 40 Cybersecurity 9 Market outlook 24 Business travel 42 Future of work ART 15 Consumer research 26 Investment in travel 45 Sustainable travel 16 Outbound 29 Aviation 49 Resilience PRODUCTION TRAVEL WEEKLY INSIGHT ANNUAL REPORT 2019-20 Editor Ian Taylor Designer and illustrator CLIENT Kate Collings Chief subeditor Mike Walsh Production manager Nick Cripps Travel Weekly Group editor-in-chief Lucy Huxley Head of sales Mary Rega Managing director Stuart Parish Jacobs Media Group chairman Clive Jacobs Front cover: Outbound holidays hit a record 47 million in 2018; numbers in 2019 were on a par and exclusive consumer research by Kantar/Service Science for this report suggests demand for overseas holidays in 2020 will at least match 2019 (page 15) Travel Weekly Insight Annual Report 2019-20 is published by Travel Weekly Group Limited. -

European Seat Capacity up 4% in W19; Wizz Air and Turkey Are Clear Winners

Issue 49 Monday 14th October 2019 www.anker-report.com Contents European seat capacity up 4% in W19; 1 European seat capacity up 4% in W19; Wizz Air and Turkey lead way. 2 Tirana to handle over 3 million Wizz Air and Turkey are clear winners passengers in 2019; Italian airlines The northern hemisphere winter aviation season (referred to as SAS. The next biggest carrier reporting double-digit growth is and routes important. W19/20 or W19) begins in just under two weeks on Sunday 27 Pobeda, now Europe’s 29th biggest carrier. The low-cost 3 Focus on: Austria, France & Greece. October. While carriers continue to fine-tune their networks, subsidiary of Aeroflot has been expanding rapidly from Moscow 4 Marseille set to break 10m pax mark especially regarding winter-only ski services, the vast majority and, more recently, St. Petersburg with winter capacity set to in 2019; Air France and Ryanair of the schedules planned for W19/20 (which finishes on grow by well over 30%. battle to be #1 carrier. Saturday 28 March 2020) should now be on sale and therefore With a nice, new airport with plenty of spare capacity to play worthy of analysis. 5 Wizz Air joins Aeroflot and British with, Turkish Airlines is the second fastest-growing carrier Around 4% increase in seats expected among Europe’s top 15 airlines, though its 6% increase is still Airways in serving UK-Russia market relatively modest compared with growth in recent years. This which peaked in 2013. Analysing the latest schedules from Cirium Data and Analytics indicates that the number of flights from European airports is growth is coming from an 11% rise in international capacity as 6 European route launch news and set to rise by 2.5% this winter, seat capacity will increase by domestic capacity is virtually unchanged from last winter. -

Finnair-Sustainability-Report-2018-Data

SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2018 RESPONSIBLE FINNAIR CLEANER CARING COLLABORATIVE ANNEX CONTENT 3 RESPONSIBLE FINNAIR 42 ANNEX 4 Push for Change 43 Reporting principles 6 Value creation model 45 Global Compact content index 7 Materiality analysis 46 GRI content index 9 Management principles 50 Independent practitioner’s limited 16 Ethics and responsible sourcing assurance report 18 CLEANER 20 Energy consumption 23 Flight noise and biodiversity 25 Emissions 27 Waste 28 CARING 29 Caring for our employees 34 Caring for our customers 35 COLLABORATIVE 36 Stakeholders 37 Economic responsibility 39 Tax footprint 2 2 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2018 RESPONSIBLE FINNAIR CLEANER CARING COLLABORATIVE ANNEX RESPONSIBLE FINNAIR Finnair’s objective is to create sustainable economic added value by producing flight services profitably, cost-competitively and in harmony with the needs of the environment and society. • Push for Change • Management Principles • Value Creation model • Ethics and Responsible • Materiality Analysis sourcing 3 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2018 RESPONSIBLE FINNAIR CLEANER CARING COLLABORATIVE ANNEX PUSH FOR CHANGE The same journey can generate more or less emissions, depending on a number of factors. By selecting a sensible form of travel, a direct and lower-emission route as well as an airline that uses modern aircraft, everyone can reduce the environmental impact of their journey. In the name of ethics, companies should not compromise on their travel, but on their emissions. Airlines decide whether to invest in modern technology, recycle waste appropriately, reduce energy consumption, and care Does this ring a bell? Climate change and all years around the world, in aviation, and That is why we must act even more deci- for the wellbeing of employees. -

Spring 2021 Corporate Finance and ERM — Strategic Decision Making Exam Case Study

Case Study SPRING 2021 Strategic Decision Making Exam EXAM CFE SDM CFESDM Table of Contents 1 RPPC Dynasty Corporation .................................................................................................................... 2 1A RPPC Dynasty Corporation Exhibits .............................................................................................. 6 2 Blue Jay Air ............................................................................................................................................ 7 2A Blue Jay Air Exhibits .................................................................................................................... 19 3 Blue Jay Tire Co ................................................................................................................................... 33 3A Blue Jay Tire Exhibits ................................................................................................................... 43 4 Frenz Corporation ............................................................................................................................... 47 4A Frenz Corporation Exhibits .......................................................................................................... 56 6 Big Ben Bank ....................................................................................................................................... 63 6A Big Ben Bank Exhibits .................................................................................................................. 73 -

Bristol Airport - Wikipedia Coordinates: 51°22′58″N 002°43′09″W Bristol Airport

09/06/2021 Bristol Airport - Wikipedia Coordinates: 51°22′58″N 002°43′09″W Bristol Airport Bristol Airport (IATA: BRS, ICAO: EGGD), at Lulsgate Bottom, on the northern slopes of the Mendip Hills, in North Bristol Airport Somerset, is the commercial airport serving the city of Bristol, England, and the surrounding area. It is 7 nautical miles (13 km; 8.1 mi) southwest of Bristol city centre.[2] Built on the site of a former RAF airfield, it opened in 1957 as Bristol (Lulsgate) Airport,[4] replacing Bristol (Whitchurch) Airport as Bristol's municipal airport. From 1997 to 2010, it was known as Bristol International Airport.[5] In 1997, a majority shareholding in the airport was sold to FirstGroup, and then in 2001 the airport was sold to a joint venture of Macquarie Bank and others. In September 2014, Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan bought out Macquarie to become the sole owner. In 2019, it was ranked the eighth busiest airport (overtaking Glasgow International Airport from the previous year) in the IATA: BRS · ICAO: EGGD United Kingdom, handling over 8.9 million passengers, a 3% Summary [6] increase compared with 2018. A passenger survey carried Airport type Public out in 2015 found that 32.5% of journeys using the airport started or ended in the city of Bristol, 9.6% in Gloucestershire, Owner Ontario Teachers' 24.5% in Somerset and 16.9% in Devon.[7] Pension Plan Serves Bristol, Somerset, Airlines with operating bases at the airport include EasyJet Gloucestershire, and Ryanair. The airport has a Civil Aviation Authority Public Herefordshire, Use Aerodrome Licence (number P432) that allows flights for the public transport of passengers and for flying instruction. -

Jacdec Safety Ranking 2013

JACDEC SAFETY RANKING 2013 Ref:http://www.jacdec.de/Airline-Rankings/jacdec_safety_ranking_2013.htm RANKNO AIRLINE CODECS COUNTRY JACDEC SAFETY INDEX 2012 1 AIR NEW ZEALAND NZ, ANZ AUS Index 0,007 2 ↑ 2 CATHAY PACIFIC AIRWAYS CX, CPA HKG Index 0,008 3 ↑ 3 FINNAIR AY, FIN FIN Index 0,010 1 ↓ 4 EMIRATES EK, UAE UAE Index 0,010 4 → 5 EVA AIR BR, EVA TWN Index 0,010 6 ↑ 6 BRITISH AIRWAYS BA, BAW GBR Index 0,011 10 ↑ 7 TAP PORTUGAL TP, TAP PRT Index 0,012 7 → 8 ETIHAD AIRWAYS EY, ETD UAE Index 0,012 5 ↓ 9 AIR CANADA AC, ACA CAN Index 0,012 25 ↑ 10 QANTAS QF, QFA AUS Index 0,013 13 ↑ 11 QATAR AIRWAYS QR, QTR QAT Index 0,013 22 ↑ 12 ALL NIPPON AIRWAYS NH, ANA JPN Index 0,015 12 → 13 VIRGIN ATLANTIC AIRWAYS VS, VIR GBR Index 0,015 15 ↑ 14 HAINAN AIRLINES HU, CHH CHN Index 0,015 8 ↓ 15 VIRGIN AUSTRALIA DJ, VOZ AUS Index 0,015 9 ↓ 16 JETBLUE AIRWAYS B6, JBU USA Index 0,015 14 ↓ 17 KLM KL, KLM NLD Index 0,015 27 ↑ 18 LUFTHANSA LH, DLH DEU Index 0,016 11 ↓ 19 SHENZHEN AIRLINES ZH, CSZ CHN Index 0,018 ★ ↑ 20 EASYJET U2, EZY GBR Index 0,018 17 ↓ 21 THOMAS COOK AIRLINES MT, TCX GBR Index 0,023 18 ↓ 22 WESTJET WS, WJA CAN Index 0,026 19 ↓ 23 TRANSAERO AIRLINES UN, TSO RUS Index 0,027 16 ↓ 24 SOUTHWEST AIRLINES WN, SWA USA Index 0,028 21 ↓ 25 JETSTAR AIRWAYS JQ, JST AUS Index 0,030 20 ↓ 26 AIR BERLIN AB, BER DEU Index 0,034 23 ↓ 27 DELTA AIR LINES DL, DAL USA Index 0,038 28 ↑ 28 THOMSON AIRWAYS BY, TOM GBR Index 0,046 26 ↓ 29 CONDOR DE, CFG DEU Index 0,050 34 ↑ 30 SINGAPORE AIRLINES SQ, SIA SGP Index 0,052 30 → 31 UNITED AIRLINES UA, UAL USA Index 0,057