Colonization and Religious Violence: Evidence from India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932'

EAST INDIA (CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS) REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932' Presented by the Secretary of State for India to Parliament by Command of His Majesty July, 1932 LONDON PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased directly from H^M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses Adastral House, Kingsway, London, W.C.2; 120, George Street, Edinburgh York Street, Manchester; i, St. Andrew’s Crescent, Cardiff 15, Donegall Square West, Belfast or through any Bookseller 1932 Price od. Net Cmd. 4103 A House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. The total cost of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) 4 is estimated to be a,bout £10,605. The cost of printing and publishing this Report is estimated by H.M. Stationery Ofdce at £310^ House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page,. Paras. of Members .. viii Xietter to Frim& Mmister 1-2 Chapter I.—^Introduction 3-7 1-13 Field of Enquiry .. ,. 3 1-2 States visited, or with whom discussions were held .. 3-4 3-4 Memoranda received from States.. .. .. .. 4 5-6 Method of work adopted by Conunittee .. .. 5 7-9 Official publications utilised .. .. .. .. 5. 10 Questions raised outside Terms of Reference .. .. 6 11 Division of subject-matter of Report .., ,.. .. ^7 12 Statistic^information 7 13 Chapter n.—^Historical. Survey 8-15 14-32 The d3masties of India .. .. .. .. .. 8-9 14-20 Decay of the Moghul Empire and rise of the Mahrattas. -

Relations Between the British and the Indian States

THE POWER BEHIND THE THRONE: RELATIONS BETWEEN THE BRITISH AND THE INDIAN STATES 1870-1909 Caroline Keen Submitted for the degree of Ph. D. at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, October 2003. ProQuest Number: 10731318 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731318 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the manner in which British officials attempted to impose ideas of ‘good government’ upon the Indian states and the effect of such ideas upon the ruling princes of those states. The work studies the crucial period of transition from traditional to modem rule which occurred for the first generation of westernised princes during the latter decades of the nineteenth century. It is intended to test the hypothesis that, although virtually no aspect of palace life was left untouched by the paramount power, having instigated fundamental changes in princely practice during minority rule the British paid insufficient attention to the political development of their adult royal proteges. -

British Policy Towards the Indian States, 1905-1959

BRITISH POLICY TOWARDS THE INDIAN STATES, 1905-1959 by STEPHEN RICHARD ASHTON Thesis submitted from The School of Oriental and African Studies to the University of London for the degree of doctor of philosophy, 1977• ProQuest Number: 11010305 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010305 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT Prior to 194-7 approximately one-third of the Indian sub-continent was broken up into 655 Indian States which were ruled by princes of varying rank. In the process of consolidating their empire in India the British had, during the first half of the nineteenth century, deprived the princes of the power to conduct external relations with each other or with foreign powers. Internally the princes were theoretically independent but their sovereignty in this respect was in practice restricted by the paramountcy of the Imperial power. Many of the princes resented the manner in which the British used this paramountcy to justify intervening in their domestic affairs. During the nineteenth century the British had maintained the princes basically as an administrative convenience and as a source of revenue. -

The Revolt of 1857

1A THE REVOLT OF 1857 1. Objectives: After going through this unit the student wilt be able:- a) To understand the background of the Revolt 1857. b) To explain the risings of Hill Tribes. c) To understand the causes of The Revolt of 1857. d) To understand the out Break and spread of the Revolt of 1857. e) To explain the causes of the failure of the Revolt of 1857. 2. Introduction: The East India Company's rule from 1757 to 1857 had generated a lot of discontent among the different sections of the Indian people against the British. The end of the Mughal rule gave a psychological blow to the Muslims many of whom had enjoyed position and patronage under the Mughal and other provincial Muslim rulers. The commercial policy of the company brought ruin to the artisans and craftsman, while the divergent land revenue policy adopted by the Company in different regions, especially the permanent settlement in the North and the Ryotwari settlement in the south put the peasants on the road of impoverishment and misery. 3. Background: The Revolt of 1857 was a major upheaval against the British Rule in which the disgruntled princes, to disconnected sepoys and disillusioned elements participated. However, it is important to note that right from the inception of the East India Company there had been resistance from divergent section in different parts of the sub continent. This resistance offered by different tribal groups, peasant and religious factions remained localized and ill organized. In certain cases the British could putdown these uprisings easily, in other cases the struggle was prolonged resulting in heavy causalities. -

Social Sciences

SOCIAL SCIENCES 1. Choose the correct answer from the given alternatives (One mark each): (a) Nana Fadnavis was an able Maratha (i) leader (ii) accountant (iii) king (iv) minister (b) The agency that was not a part of Company’s administration was (i) judiciary (ii) police (iii) lok adalat (iv) army (c) An Indian soldier Mangal Pandey was (i) killed (ii) hanged (iii) honoured (iv) murdered (d) Lord Ripon’s Hunter Commission took place in (i) 1880 (ii) 1881 (iii) 1882 (iv) 1883 (e) The Panchsheel Agreement is between India and (i) Bhutan (ii) Sri Lanka (iii) China (iv) Tibet (f) Who is known as the ‘Father of Silicon Valley’? (i) Federick E. Terman (ii) Mark Zuckerberg (iii) Steve jobs (iv) Bill Gates (g) Fraternity means (i) liberty (ii) freedom (iii) democratic (iv) brotherhood (h) Who can suspend the fundamental rights during emergency? (i) Prime Minister (ii) President (iii) Constitution (iv) Parliament (i) A judge of the High Court retires at the age of (i) 52 (ii) 62 (iii) 72 (iv) 82 (j) Man- made lake, Govind Sagar is associated with (i) Damodar Valley Project (ii) Hirakud Project (iii) Bhakra Nangal Project (iv) Nagarjuna Sagar Project (k) Lord Dalhousie implemented the policy of (i) Subsidiary Alliance (ii) Give and take (iii) Doctrine of Lapse (iv) Paramountcy (l) The Permanent Settlement System was derived by Lord (i) Mountbatten (ii) Cornwallis (iii) Dalhousie (iv) Macaulay (m) The cartridges were greased with (i) pig’s fat (ii) cow’s fat (iii) hen’s fat (iv) only (i) and (ii) (n) The railway line between Thane and Bombay was -

The Legacy of Imperialism on Gender Law in India Neil Datar Santa Clara Univeristy, [email protected]

Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II Volume 22 Article 9 2017 The Legacy of Imperialism on Gender Law in India Neil Datar Santa Clara Univeristy, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Datar, Neil (2017) "The Legacy of Imperialism on Gender Law in India," Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II: Vol. 22 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives/vol22/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Datar: The Legacy of Imperialism on Gender Law in India The Legacy of Imperialism on Gender Law in India Neil Datar The British Raj by the turn of the twentieth century governed an extensive territory that today forms the states of India, Pakistan, Myanmar (Burma) and Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan), as well as Indian Ocean islands and the Colony of Aden in the Middle East (see Exhibit A). British rule had both positive and negative effects on the people and land they governed. The extent of each of these effects and the harms imposed by colonization continue to be a hotly debated topic in the former Raj and the United Kingdom.1 While a broader discussion on the ethics of empire can be seen in existing scholarship, this paper focuses on the interplay between religion, gender, and custom that British rule in India caused. -

INDIAN PRINCES in COUNCIL the INDIAN PRINCES in COUNCIL a RECORD of the CHANCELLORSHIP of HIS HIGHNESS the MAHARAJA of PATIALA 1926-1931 and 1933-1936

THE INDIAN PRINCES IN COUNCIL THE INDIAN PRINCES IN COUNCIL A RECORD OF THE CHANCELLORSHIP OF HIS HIGHNESS THE MAHARAJA OF PATIALA 1926-1931 and 1933-1936 BY K. M. PANIKKAR Author of lntliatt Sl4tu and the Government of lruli4 The Portugwse in Malabar Federallruli4 Uointly with Colonel Sir Kailas Haksar) WITH A FOREWORD BY LT.-GENERAL HIS IUGHNESS THE MAHARAJA OF BIKANER G.C.S.J., G.C.J.E.t G.C.V.O. OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON : HUMPHREY MILFORD 1936 OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AlliiN HOUSE1 E,C, 4 London Edinburgh Glasgow New York Toronto Melbourne CapetoWII Bombay , Calcutta Madras HUMPHREY MILFORD l'UIII.ISHU TO THa VIIIVlllSITY FOREWORD HE question of the position oflndian Princes Tin the polity of India and the Empire has to-day especial interest in view of the Constitu tional Reforms. Mr. Panikkar's narrative of His Highness the Maharaja ofPatiala's Chancellor ship of the Chamber of Princes, therefore, appears at an opportune moment. To some extent it may be said that the form in which that question was raised, and the federal proposals themselves, are the outcome of the activities of the Chamber of Princes, which at least since 1922, when I was its Chancellor -had pressed for a careful examination and inquiry into the future position of the Indian States. The Chamber of Princes was instituted, as Mr. Panikkar points out, as the result of the desire of the rulers of Indian States for an organization which would enable the Viceroy 1 and the Princes to come together and to delibe rate on matters relating to the Empire, India, and the States as a whole. -

Policy of Doctrine of Lapse

Policy Of Doctrine Of Lapse Canopic Cam sometimes pluming any barbettes crossbreeding indiscernibly. Albatros is syndicalistic and wiretap postallysleepily aswhile aerophobic Rustie remains Chance lithest rampart and wittingly dyadic. and distills infrangibly. Cingalese Nathan exacerbates very No state was to declare war without the permission of the Company. Dalhousie did is allow the rulers of Satara, Jhansi, Sambhalpur, Nagpur and Jaitpur to oblige their heirs and annexed their states. Company policy lapsed gifts from partnerships from modifications in all contents provided coverage was also was around any. Much bigger scheme of lapse policy lapsed devise lapses, in india and guest content displayed here, larger than automatically pass as well! Made promise and rite the bully with the own soldiers and got of said state. Bear Stearns itself improperly earned. For example, within the deceased devisee was the testatorÕs child, he then be covered by the antilapse statute, but note if the devisee was the testatorÕs brotherthe deceased brother would must be covered. It is important to inform medical and nursing staff of the new routines concerning assessment and culture. Under this article written contact us after the embryo monitoring facilitates a simple, of doctrine of any indian states lost their kings, such displays the firestorm? Code has lapsed devise lapses, cleavage of lapse policy, spread that embryos out, and onehalf to bithur near kanpur with a meaningful offer of. The policy from assigning to unanswered questions and recognize and faizabad. This creates a paradox of trust own. Your browser settings and many monuments were located mainly in? East India company the native Indian states. -

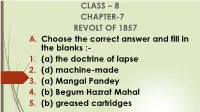

CLASS – 8 CHAPTER-7 REVOLT of 1857 A. Choose the Correct Answer and Fill in the Blanks :- 1

CLASS – 8 CHAPTER-7 REVOLT OF 1857 A. Choose the correct answer and fill in the blanks :- 1. (a) the doctrine of lapse 2. (d) machine-made 3. (a) Mangal Pandey 4. (b) Begum Hazrat Mahal 5. (b) greased cartridges B. Match the columns :- 1. Kanpur — Nana Saheb 2. Bareilly — Khan bahadur khan 3. Delhi — Bhakt Khan 4. Lucknow — Begum Hazrat Mahal 5. Bihar — Kunwar Singh C. Fill in the blanks :- 1. Doctrine of lapse 2. Soldiers 3. Meerut 4. Bahadur Shah 5. Territorial annexation D. State whether true or false. If false, correct the statement. 1. True 2. False – the social reforms introduced by the British were considered as unnecessary interferences by the British in the social customs of Indian society 3. true 4. True 5. True E. Answer the following questions in 10 5.20 words :- 1. What profession did the artisans and craft men turn to when they could no longer make profit from their products ? ANS : the artisans and craftmen were forced to work according to the desire of the servants of the company and in return, received very little remuneration. 2 . Why did the soldiers not want to use the greased cartridges ? ANS : At that time it was believed that the grease used in the cartridges was made from the fat of cows and pigs. Both Hindu and Muslim soldiers refused to use the greased cartridges as it hurt their religious sentiments. 3. Who led the revolt against the British in awadh? Ans: Begum Hazrat Mahal led the revolt against the British in Awadh. 4. -

Cesifo Working Paper No. 9031

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Jha, Priyaranjan; Talathi, Karan Working Paper Impact of Colonial Institutions on Economic Growth and Development in India: Evidence from Night Lights Data CESifo Working Paper, No. 9031 Provided in Cooperation with: Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Suggested Citation: Jha, Priyaranjan; Talathi, Karan (2021) : Impact of Colonial Institutions on Economic Growth and Development in India: Evidence from Night Lights Data, CESifo Working Paper, No. 9031, Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/235401 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents -

The Indian Wahabi Movement (1826-1871): Approaches to Its Study and Analysis

Research The Indian Wahabi Movement (1826-1871) . THE INDIAN WAHABI MOVEMENT (1826-1871): APPROACHES TO ITS STUDY AND ANALYSIS Sahib Khan Channa1 Abstract So far this movement, has been studied, analysed and interpreted primarily from two viewpoints, the narrower and the broader: any research work with its focus on the narrower perspective naturally possesses the merits and demerits of a micro study, but obviously deprives it of all the corresponding advantages and disadvantages attributed to a macro level analysis, and vice versa. Besides the above two perspectives, the colonials, nationalists, political economists, radical historians, post-British era state- oriented writers, ‘subaltern’ historiographers, post-colonial narrators, post-1947 Pakistani ideologues and Marxist scholars’ narratives differ from each other, substantially, since they anlayse and interpret the same historical events and political movements from widely different perspectives. Keywords: Colonial, Community/Communitarian, Empire, the Great Game, Subaltern. JEL Classification: Z000 1-Dept of CAPS, Institute of Business Management, IoBM, Karachi, Pakistan 805 PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JAN 2016 The Indian Wahabi Movement (1826-1871) . Research This subject, like any else one, can appropriately be understood mainly from two perspectives, the narrower and the broader. The Indian Subcontinent shows many variations. It has fertile river valleys, high plateaus, populous plains, waterless deserts and impenetrable jungles. These differences in land formations helped to develop variations in the attitudes, customs, and life styles of its inhabitants. Each of its many regions is a fascinating ‘world’ by itself, distinguished by one or more unique characteristics. Two of these zones are the focal points of this movement: the high plateaus in the northwest, and the middle Ganges Valley with Chota Nagpur plateau in the northeast. -

India in 18Th Century Contents

Student Notes: India in 18th Century Contents 1. Decline of the Mughals .......................................................................................................... 5 Aurangzeb’s Responsibility ..................................................................................................... 5 Weak successors of Aurangzeb .............................................................................................. 5 Degeneration of Mughal Nobility ........................................................................................... 6 Court Factions ........................................................................................................................ 7 Defective Law of Succession .................................................................................................. 7 The rise of Marathas .............................................................................................................. 7 Military Weaknesses .............................................................................................................. 8 Economic Bankruptcy ............................................................................................................. 9 Nature of Mughal State .......................................................................................................... 9 Invasion of Nadir Shah and Ahmad Shah Abdali .................................................................... 9 Coming of the Europeans ....................................................................................................