Front Matter, the Formation and Stocks of Total Capital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monica Prasad Northwestern University Department of Sociology

SPRING 2016 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW COLLOQUIUM ON TAX POLICY AND PUBLIC FINANCE “The Popular Origins of Neoliberalism in the Reagan Tax Cut of 1981” Monica Prasad Northwestern University Department of Sociology May 3, 2016 Vanderbilt-208 Time: 4:00-5:50 pm Number 14 SCHEDULE FOR 2016 NYU TAX POLICY COLLOQUIUM (All sessions meet on Tuesdays from 4-5:50 pm in Vanderbilt 208, NYU Law School) 1. January 19 – Eric Talley, Columbia Law School. “Corporate Inversions and the unbundling of Regulatory Competition.” 2. January 26 – Michael Simkovic, Seton Hall Law School. “The Knowledge Tax.” 3. February 2 – Lucy Martin, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Political Science. “The Structure of American Income Tax Policy Preferences.” 4. February 9 – Donald Marron, Urban Institute. “Should Governments Tax Unhealthy Foods and Drinks?" 5. February 23 – Reuven S. Avi-Yonah, University of Michigan Law School. “Evaluating BEPS” 6. March 1 – Kevin Markle, University of Iowa Business School. “The Effect of Financial Constraints on Income Shifting by U.S. Multinationals.” 7. March 8 – Theodore P. Seto, Loyola Law School, Los Angeles. “Preference-Shifting and the Non-Falsifiability of Optimal Tax Theory.” 8. March 22 – James Kwak, University of Connecticut School of Law. “Reducing Inequality With a Retrospective Tax on Capital.” 9. March 29 – Miranda Stewart, The Australian National University. “Transnational Tax Law: Fiction or Reality, Future or Now?” 10. April 5 – Richard Prisinzano, U.S. Treasury Department, and Danny Yagan, University of California at Berkeley Economics Department, et al. “Business In The United States: Who Owns It And How Much Tax Do They Pay?” 11. -

Distributional Implications of Introducing a Broad-Based Consumption Tax

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Tax Policy and the Economy, Volume 11 Volume Author/Editor: James M. Poterba, editor Volume Publisher: MIT Volume ISBN: 0-262-16167-2 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/pote97-1 Conference Date: October 22, 1996 Publication Date: January 1997 Chapter Title: Distributional Implications of Introducing a Broad-Based Consumption Tax Chapter Author: William M. Gentry, R. Glenn Hubbard Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10904 Chapter pages in book: (p. 1 - 48) DISTRIBUTIONAL IMPLICATIONS OF INTRODUCING A BROAD-BASED CONSUMPTION TAX William M. Gentry and R. Glenn Hubbard Columbia University and N.B.E.R. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As a tax base, "consumption" is sometimes argued to be less fair than "income" because the benefits of not taxing capital income accrue to high- income households. We argue that, despite the common perception that consumption taxation eliminates all taxes on capital income, consumption and income taxes actually treat similarly much of what is commonly called capital income. Indeed, relative to an income tax, a consumption tax exempts only the tax on the opportunity cost of capital. In contrast to a pure income tax, a consumption tax replaces capital depreciation with This paper was prepared for presentation at the NBER Conference on Tax Policy and the Economy, Washington, DC, October 22, 1996. We are grateful to Alan Auerbach, Joe Bankman, Tom Barthold. Doug Bemheim, Michael Boskin, Dave Bradford, Martin Feld- stein, Bill Gale, Larry Goulder, Jane Gravelle, Hank Gutman, Ken Judd, Louis Kaplow, Mary Kosters, Jim Nunns, Jim Poterba, Karl Scholz, Eric Toder, Al Warren, the Columbia Micro Lunch Group, the Harvard-M.I.T. -

Uncorrected Transcript

1 CEA-2016/02/11 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION FALK AUDITORIUM THE COUNCIL OF ECONOMIC ADVISERS: 70 YEARS OF ADVISING THE PRESIDENT Washington, D.C. Thursday, February 11, 2016 PARTICIPANTS: Welcome: DAVID WESSEL Director, The Hutchins Center on Monetary and Fiscal Policy; Senior Fellow, Economic Studies The Brookings Institution JASON FURMAN Chairman The White House Council of Economic Advisers Opening Remarks: ROGER PORTER IBM Professor of Business and Government, Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government, The John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University Panel 1: The CEA in Moments of Crisis: DAVID WESSEL, Moderator Director, The Hutchins Center on Monetary and Fiscal Policy; Senior Fellow, Economic Studies The Brookings Institution ALAN GREENSPAN President, Greenspan Associates, LLC, Former CEA Chairman (Ford: 1974-77) AUSTAN GOOLSBEE Robert P. Gwinn Professor of Economics, The Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago, Former CEA Chairman (Obama: 2010-11) PARTICIPANTS (CONT’D): GLENN HUBBARD Dean & Russell L. Carson Professor of Finance and Economics, Columbia Business School Former CEA Chairman (GWB: 2001-03) ALAN KRUEGER Bendheim Professor of Economics and Public Affairs, Princeton University, Former CEA Chairman (Obama: 2011-13) ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 2 CEA-2016/02/11 Panel 2: The CEA and Policymaking: RUTH MARCUS, Moderator Columnist, The Washington Post KATHARINE ABRAHAM Director, Maryland Center for Economics and Policy, Professor, Survey Methodology & Economics, The University of Maryland; Former CEA Member (Obama: 2011-13) MARTIN BAILY Senior Fellow and Bernard L. Schwartz Chair in Economic Policy Development, The Brookings Institution; Former CEA Chairman (Clinton: 1999-2001) MARTIN FELDSTEIN George F. -

What Is Labor Supply and Do Taxes Affect It?

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES WHAT IS LABOR SUPPLY AND DO TAXES AFFECT IT? Harvey S. Rosen Working Paper No. 411 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge MA 02138 November 1979 The research reported here is part of the NBER's research program in Taxation. Any opinions expressed are those of the author and not those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. Support was provided by NSF Grant No. SOC-7907847. I would like to thank C. Reimers, P. Hendershott, J. Eaton and J. Pechman for useful suggestions. This paper was prepared for presentation at the meetings of the American Economics Association, December, 1979. NBER Working Paper 411 November 1979 What is Labor Supply and Do Taxes Affect it? ABSTRACT There is a large econometric literature on the impact of income taxes on hours of work and labor force participation rates. It has long been understood, however, that the concept "labor supply" is more general than "hours of work." Individual differences in skills, motivation and health will influence the effective labor supply associated with any given number of hours of work. The purpose of this paper is to suggest some ways by which it might be possible to learn something about the effects of taxes on these other, and possibly very important, dimensions of labor supply. Harvey S. Rosen Department of Economics Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544 609/452-4000 The issue of tax induced changes in labor supply behavior has been re ceiving increasing attention. Economic theory alone can say little about the impact of income taxation on labor supply because of the well known conflict between income and substitutiQO effects. -

Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress

Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress Professor Joseph E. STIGLITZ, Chair, Columbia University Professor Amartya SEN, Chair Adviser, Harvard University Professor Jean-Paul FITOUSSI, Coordinator of the Commission, IEP www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr Other Members Bina AGARWAL University of Delhi Kenneth J. ARROW StanfordUniversity Anthony B. ATKINSON Warden of Nuffield College François BOURGUIGNON School of Economics, Jean-Philippe COTIS Insee, Angus S. DEATON Princeton University Kemal DERVIS UNPD Marc FLEURBAEY Université Paris 5 Nancy FOLBRE University of Massachussets Jean GADREY Université Lille Enrico GIOVANNINI OECD Roger GUESNERIE Collège de France James J. HECKMAN Chicago University Geoffrey HEAL Columbia University Claude HENRY Sciences-Po/Columbia University Daniel KAHNEMAN Princeton University Alan B. KRUEGER Princeton University Andrew J. OSWALD University of Warwick Robert D. PUTNAM Harvard University Nick STERN London School of Economics Cass SUNSTEIN University of Chicago Philippe WEIL Sciences Po Rapporteurs Jean-Etienne CHAPRON INSEE General Rapporteur Didier BLANCHET INSEE Jacques LE CACHEUX OFCE Marco MIRA D’ERCOLE OCDE Pierre-Alain PIONNIER INSEE Laurence RIOUX INSEE/CREST Paul SCHREYER OCDE Xavier TIMBEAU OFCE Vincent MARCUS INSEE Table of contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I. SHORT NARRATIVE ON THE CONTENT OF THE REPORT Chapter 1: Classical GDP Issues . 21 Chapter 2: Quality of Life . 41 Chapter 3: Sustainable Development and Environment . 61 II. SUBSTANTIAL ARGUMENTS PRESENTED -

"What Can an Economic Adviser Do When the President Adopts Bad Economic Policies?"

"What Can An Economic Adviser Do When the President Adopts Bad Economic Policies?" Jeffrey Frankel, Harpel Professor, KSG, Harvard University The Pierson Lecture, Swarthmore, April 21, 2005 Summary: What would you do if you were appointed Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under a president who was committed to one or more specific policies that you considered to be inconsistent with good economics? A look at the experiences of your predecessors over the last 40 years might help illustrate your alternative options. The lecture will review the history. It will then go on to suggest that such conflicts should be particularly acute in the current Administration. The reason is that Republican presidents have increasingly adopted policies-- with regard particularly to budget deficits, trade, the size of government, and inflation -- that deviate from the principles of good economics, and that used to be considered the weaknesses of Democratic presidents. It is a great honor to be giving the Pierson lecture.1 I must confess that I never had Frank Pierson for a course. But he was the senior eminence of the Economics Department when I attended Swarthmore in the early 1970s, having already been associated with the department more than 40 years. In that time, Frank Pierson was known as one of the last professors who still regularly held his honors seminars at his house, with an impressive series of desserts, including make-your-own sundaes, and Irish coffee. The early 1970s were a volatile time of course, with the War in Viet Nam still on.2 In 1972 the big split on campus was between those of us working for McGovern on the left, and the 1 The author wishes to acknowledge help from Peter Jaquette, Arnold Kling, Jeff Miron, Stephen O’Connell, Francis Bator, Michael Boskin, David Cutler, Jason Furman, Gilbert Heebner, William Gale, Jeff Liebman, Peter Orszag, Roger Porter, Charles Schultze, Phillip Swagel, Laura Tyson, Murray Weidenbaum, Marina Whitman, and Janet Yellen. -

A N N U a L R E P O R T

A N N U A L R E P O R T 2014 – 2015 SIEPR’s Mission The Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research supports research, trains undergraduate and graduate students, and shares nonpartisan scholarship that will lead to better economic policies in the United States and abroad. Table of Contents From the Director 2 New Faculty 4 Policy Impact 6 Young Scholars Program 8 Student Support 9 Events and Conferences 14 Policy Briefs 18 Income and Expenditures 19 Research Centers and Programs 20 Development 24 Donors 28 Visitors 32 Senior Fellows 34 Steering Committee 38 Advisory Board 39 ANNUAL REPORT | 2014 – 2015 1 From the Director Dear Friends, My first six months as the Trione Director of the undergraduates working as research assistants with Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research have been SIEPR scholars. We have also organized a number of marked with significant activity. We added more than a policy forums that were geared toward students, including dozen faculty to our Senior Fellow ranks in the Fall. They one on innovation challenges for the next presidential include Professors from the Department of Economics administration and others that focused on the “app along with the schools of Business, Education, Law, and economy” and the evolution of finance. Medicine. We also welcomed 11 Assistant Professors as We have hosted some of the most important and Faculty Fellows. These additions mean SIEPR’s arsenal of influential leaders in government and business who have expertise on economic policy includes more shared with us their insights on economic than 80 faculty from all seven Stanford schools policy and many other issues. -

Open PDF File, 8.71 MB, for February 01, 2017 Appendix In

Case 4:16-cv-00469-K Document 175 Filed 02/01/17 Page 1 of 10 PageID 5923 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS FORT WORTH DIVISION EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION, § § Plaintiff, § v. § No. 4:16-CV-469-K § ERIC TRADD SCHNEIDERMAN, § Attorney General of New York, in his § official capacity, and MAURA TRACY § HEALEY, Attorney General of § Massachusetts, in her official capacity, § § Defendants. § APPENDIX IN SUPPORT OF EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION’S BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF THIS COURT’S PERSONAL JURISDICTION OVER THE DEFENDANTS Exhibit Description Page(s) N/A Declaration of Justin Anderson (Feb. 1, 2017) v – ix A Transcript of the AGs United for Clean Power App. 1 –App. 21 Press Conference, held on March 29, 2016, which was prepared by counsel based on a video recording of the event. The video recording is available at http://www.ag.ny.gov/press- release/ag-schneiderman-former-vice-president- al-gore-and-coalition-attorneys-general-across B E-mail from Wendy Morgan, Chief of Public App. 22 – App. 32 Protection, Office of the Vermont Attorney General to Michael Meade, Director, Intergovernmental Affairs Bureau, Office of the New York Attorney General (Mar. 18, 2016, 6:06 PM) C Union of Concerned Scientists, Peter Frumhoff, App. 33 – App. 37 http://www.ucsusa.org/about/staff/staff/peter- frumhoff.html#.WI-OaVMrLcs (last visited Jan. 20, 2017, 2:05 PM) Case 4:16-cv-00469-K Document 175 Filed 02/01/17 Page 2 of 10 PageID 5924 Exhibit Description Page(s) D Union of Concerned Scientists, Smoke, Mirrors & App. -

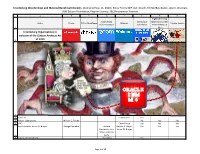

Interlocking Directorships and Material Beneficial Interests. (Compiled Sep

Interlocking Directorships and Material Beneficial Interests. (Compiled Sep. 21, 2020). Entity Forms DEF 14A: Oracle, TikTok/ByteDance, Zoom, Walmart, IBM Eclipse Foundation, Pilgrims Society. SEC/Anonymous Patriots. A B C D E F G H Highlands Group Zoom Video IBM Eclipse (DoD Office of Net Entity Oracle TikTok/ByteDance Walmart Pilgrims Society Communications Foundation Assessment), UK 1 MI6 Interlocking Organizations in violation of the Clayton Antitrust Act 2 of 1914 ORACLE IBM MI6 3 4 2023 LLC Cesar Conde Yes 5 Abbott Laboratories William G. Parrett Yes Yes Yes 6 ABC Cesar Conde Yes Yes Yes Accel Partners, James W. Breyer George Conrades Richard Marissa A. Mayer, Yes Yes Yes Yanowitch, John James W. Breyer Dillon, Goldman 7 Sachs 8 Adams Street Partners John Dillon Yes Page 1 of 15 Interlocking Directorships and Material Beneficial Interests. (Compiled Sep. 21, 2020). Entity Forms DEF 14A: Oracle, TikTok/ByteDance, Zoom, Walmart, IBM Eclipse Foundation, Pilgrims Society. SEC/Anonymous Patriots. A B C D E F G H Highlands Group Zoom Video IBM Eclipse (DoD Office of Net Entity Oracle TikTok/ByteDance Walmart Pilgrims Society Communications Foundation Assessment), UK 1 MI6 Interlocking Organizations in violation of the Clayton Antitrust Act 2 of 1914 Adobe Systems Bruce R. Chizen Donna Morris Yes Yes Yes Highlighted in yellow are 84 material, direct, undisclosed associations with the British Crown's Privy Council who is directing PRC Chinese financial and political priorities to turn America communist & controlled by British imperialist corporatism directed by the Pilgrims Society. 9 10 African Development Bank Suresh Kumar Yes 11 Airtime.com Marissa A. -

Printmgr File

September 18, 2020 To our Stockholders: You are cordially invited to attend the 2020 Annual Meeting of Stockholders of Oracle Corporation. Our Annual Meeting will be held on Wednesday, November 4, 2020, at 10:00 a.m., Pacific Time. In light of the COVID-19 outbreak, for the safety and well-being of our stockholders, directors and employees, and taking into account the protocols of local, state and federal governments, we have determined that this year’s Annual Meeting will be held in a virtual format only. At our virtual Annual Meeting, stockholders will be able to attend, vote and submit questions via the Internet. Our goal is to continue to serve the needs of our stockholders without significant disruption while closely monitoring developments related to the COVID-19 pandemic to keep our stockholders, directors and employees safe. We describe in detail the actions we expect to take at the Annual Meeting in the following Notice of 2020 Annual Meeting of Stockholders and proxy statement. We have also made available a copy of our Annual Report on Form 10-K for fiscal 2020. We encourage you to read the Form 10-K, which includes information on our operations, products and services, as well as our audited financial statements. This year, we will again be using the “Notice and Access” method of providing proxy materials to stockholders via the Internet. We believe that this process provides stockholders with a convenient and quick way to access the proxy materials and vote, while allowing us to conserve natural resources and reduce the costs of printing and distributing the proxy materials. -

Tax Policy and Economic Growth: Lessons from the 1980S Author(S): Michael J

American Economic Association Tax Policy and Economic Growth: Lessons From the 1980s Author(s): Michael J. Boskin Source: The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 2, No. 4 (Autumn, 1988), pp. 71-97 Published by: American Economic Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1942778 Accessed: 05/01/2010 02:01 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aea. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Economic Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Economic Perspectives. http://www.jstor.org Journalof EconomicPerspectives- Volume 2, Number4 -Fall 1988-Pages 71-97 Tax Policy and EconomnicGrowth: Lessons From the 1980s Michael J. -

A Book on Tax Reform

Transition Costs of Fundamental Tax Reform Transition Costs of Fundamental Tax Reform Kevin A. Hassett and R. Glenn Hubbard The AEI Press Publisherfor the American Enterprise Institute WASHINGTON, D.C. 2001 Distributed to the Tmde by National Book Network, 15200 NBN Way, Blue Ridge Summit, PA 17214. To order call toll free 1-800-462-6420 or 1-717-794-3800. For all other inquiries please contact the AEI Press, 1150 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 or call 1-800-862-5801. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hassett, Kevin A. Transition Costs of Fundamental Tax Reform Kevin A. Hassett and R. Glenn Hubbard p. cm. Essays prepared for an AEI conference Includes bibliographical references ISBN 0-447-4111-6 (cloth : alk. paper)-ISBN 0-8447-4112-4 (pbk. alk. paper) 1. Taxation-United States-Congresses. 2. Taxation-Economic aspects-United States-Congresses. 3. Spending tax-United States- Congresses. I. Hubbard, R. Glenn. II. Title. HJ2381.H344 2001 336.2'05'0973--dc21 135 79108642 © 2001 by the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Washington, D.C. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in cases of brief quotations embod- ied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. The AEI Press Publisher for the American Enterprise Institute 1150 17th Street, N.W, Washington, D.C.