The Value of Food in Rural China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Din Tai Fung As a Global Shanghai Dumpling House Made in Taiwan Haiming Liu

Flexible Authenticity Din Tai Fung as a Global Shanghai Dumpling House Made in Taiwan Haiming Liu Haiming Liu, “Flexible Authenticity: Din Tai Fung as a Global known in Taiwan, Hong Kong, or mainland China. Chinese Shanghai Dumpling House Made in Taiwan,” Chinese America: food in America reflected the racial status of Chinese Ameri- History & Perspectives —The Journal of the Chinese Histori- cans. The Chinese restaurant business, like the laundry busi- cal Society of America (San Francisco: Chinese Historical Soci- ness, was a visible menial-service occupation for Chinese ety of America with UCLA Asian American Studies Center, 2011), immigrants and their descendants. 57–65. Ethnic food also reflects immigration history. After the 1965 immigration reform, new waves of Chinese immigrants arrived. Between 1965 and 1984, an estimated 419,373 Chi- CHANGES IN THE CHINESE AMERICAN nese entered the United States.5 Post-1965 Chinese immi- REstaURANT BUSINESS grants were far more diverse in their class and cultural back- grounds than the earlier immigrants had been. Many were n December 4, 2007, the Taiwan government spon- educated professionals, engineers, technicians, or exchange sored Din Tai Fung, a steamed dumpling house in students. Their arrival fostered a new, booming Chinese res- Taipei, to hold a gastronomic demonstration in Paris taurant business in America, especially in regions such as O 1 as a diplomatic event to promote its “soft power.” Though the San Gabriel Valley in Southern California and Queens in the cooking show was held by a pro-independence regime, New York, where Chinese populations concentrated. the restaurant actually featured Shanghai cuisine rather than Accordingly, food in Chinese restaurants in Amer- native Taiwanese food. -

Yilan Handbook 2011-2012

About FSE The Foundation for Scholarly Exchange (formerly known as the U.S. Educational Foundation in the Republic of China), supported mainly by Taiwan’s Ministry of Education (MOE), Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), and U.S. Department of State via the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT), is one of 51 bi-national/bilateral organizations in the world established specifically to administer the Fulbright educational exchange program outside the U.S. Ever since 1957, the Foundation has financed over 1400 Taiwan Fulbright grantees to the U.S. and more than 1000 U.S. Fulbright grantees coming to Taiwan. In 1962, the Foundation started the U.S. Education Information Center for Taiwan students who need information or guidance about studying in the U.S. Since 2003, the Foundation has cooperated with Yilan County Government to organize the Fulbright ETA project, with a view to providing high-quality English instruction to students in the county’s junior middle and elementary schools. Later, in 2008, the Kaohsiung City Government and the Foundation jointly began to deliver a similar ETA program in Kaohsiung. Currently, there are 28 Fulbright ETA grantees participating in this special project in both places. FSE is overseen by a Board of Directors comprising five Taiwanese and five U.S. members, with the director of the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT) as the Honorary Chairman of the Board. The Fulbright Program The Fulbright Program was established in 1946 in the aftermath of WWII, as an initiative of Senator J. William Fulbright of Arkansas, who believed that a program of educational and cultural exchange between the people of the United States and those of other nations could play an important role in building lasting world peace. -

Steaming Is a Pure, Simple and Almost Is a Pure, Simple and Steaming Back of Cooking

STEAM CONTRIBUTORS STEAM Steaming is a pure, simple and almost spiritual way of cooking. Dating back TEXT to prehistoric times when food was Tan Su-Lyn wrote Lonely Planet’s cooked over hot springs, this culinary . World Food Guide: Malaysia and technique has since inspired chefs T Singapore, and co-authored chef, HE across the globe to harness its Jereme Leung’s cookbook, delicate heat by developing New Shanghai Cuisine. She was implements such as multi-tiered formerly the managing editor of S steamers, tagines and even recipes PIRIT Wine & Dine magazine. where food is cooked en papillote (where ingredients are sealed in PHOTOGRAPHY paper to steam in their own juices). Alexander Haselhoff spent several years in the USA working on the O To steam food is to cook ingredients Marlboro advertising campaign F LIF by enveloping them in water vapour which led to numerous awards and in a sealed vessel. This method of exhibitions. He has since contributed cooking provides even, moist heat to over 40 German cookbooks. and leaves fish, poultry and E vegetables naturally tender. Precious DESIGN nutrients are retained. Flavours Art Director Chris Wee’s Lincoln remain clean and clear. And colours Modern hardback book, created for stay true. SC Global, won an Asia Graphics Award in 2001. His work on Shopping As leading creators of top-quality magazine also won a Gold Award at appliances, Miele has naturally sought Publish Asia 2002. to produce the ultimate steamer for the contemporary kitchen. Even so, our commitment goes well beyond simply creating a highly functional machine with a sleek design. -

2018 Winter 25(4)

FFlavorlavor & Fortune D edicated T o T he A rt A nd S cience O f C hinese C uisine staPLE foods: RICE AND WHeat; CHINESE food IN THE US; THE CHINESE KIWI SILK ROAD CULINARY INFLUENCES; NAXI PEOPLE ARE KNOWN BY MANY NAMES; BOOK AND restauraNT REVIEWS, AND mucH more. Fall 2018 V olume 25(4) $6.95 US/ $9.95 Elsewhere 2 F lavor & F ortune WINTER 2018 FFlavorlavor & Fortune Volume 25, Number 4 Winter 2018 Food For Thought ........................................................................... 2 About the Publisher; Table of Contents; Dear Reader Letters to the Editor ....................................................................... 5 Spice rub; Recipe increase; Chinese God; Yin/Yang cooking methods. Gingko; The oldest Chinatowns; Marco Polo in jail; Kudos; Dongzhi; and other queries; Duck tongue recipes; Xiao Long Bao STAPLE FOODS: RICE AND WHEAT .................................................. 9 KIWI: GOOSEBERRY IS STILL CALLED A YANG--TAO .................. 15 NAXI: A MINORITY WITH MANY NAMES .................................16 ON OUR BOOKSHELVES ..................................................................19 Chop Suey and Sushi from Sea to Shining Sea edited by Bruce Makato Arnold; Tanfer Emin; and Raymond Douglas Chong Land of the Five Flavors, The by Thomas O. Hollman Asian Cuisines edited by Karen Christensen CHINESE FOOD IN THE U.S ............................................................22 EARLY CHINESE COOKBOOKS ........................................................24 SILK ROAD CULINARY INFLUENCES .............................................25 -

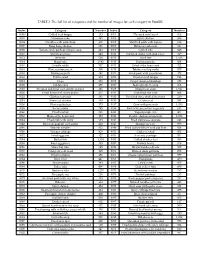

TABLE 2: the Full List of Categories and the Number of Images for Each Category in Food2k

TABLE 2: The full list of categories and the number of images for each category in Food2K. Index Category Number Index Category Number 0000 Grilled beef tongue 293 0001 Flavored snail meat 416 0002 Napoleon cake 462 0003 Spicy chicken 388 0004 Noodles with pork chop 499 0005 Stir-fried pork with capers 238 0006 Bang bang chicken 861 0007 Hibiscus crab stick 341 0008 Tomato and egg flour pimple soup 843 0009 Grilled ribs 343 0010 Stir-fried lettuce 240 0011 Stir-fried clams with chili sauce 329 0012 Brownie 500 0013 Duck feet 1,818 0014 Hand cake 1,082 0015 Durian pancake 434 0016 Griddle rabbit 397 0017 Dried chiba bean curd 422 0018 Plate reinforcement 309 0019 Tobiko warship sushi 577 0020 Meringue puffs 462 0021 Fried pork with sauerkraut 475 0022 Potato salad 490 0023 Onion mixed fungus 742 0024 Crepe 362 0025 Crispy chicken bibimbap 673 0026 Golden cake 496 0027 Bean sprouts in soup 478 0028 Steamed fish head with double pepper 381 0029 Mung bean soup 1,947 0030 Good harvest of coarse grains 211 0031 Crab fried rice cake 466 0032 Chicken casserole 381 0033 Pan-fried three stuffed treasures 230 0034 Firewood chicken 480 0035 Golden cod 336 0036 Waxiang chicken 375 0037 Corn with pine nuts 1,033 0038 Secret jujube 765 0039 Pork with preserved vegetable 982 0040 Fried hairtail 601 0041 Yogurt purple rice 401 0042 Home-style bean curd 463 0043 Double chicken drumsticks 1,010 0044 Fried crab with curry 513 0045 Fried cantonese sausage 242 0046 Roasted eggplant with garlic 628 0047 Shrimp skewers 999 0048 Wonton noodles 812 0049 Fried kidney -

Hotel Restaurant Institutional Taiwan

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 12/16/2015 GAIN Report Number: TW15049 Taiwan Food Service - Hotel Restaurant Institutional Food Service Growth Shows No Signs of Slowing Down Approved By: Mark Ford Prepared By: Cleo Fu Report Highlights: The food service revenue in Taiwan increased for the ninth year in a row to NT$413 billion (US$13 billion) in 2014, up 3.1 percent from the previous year. A further confirmation of the sector’s continued success, several international food service chains recently opened their first Taiwan outlet. Post anticipates Taiwan’s food service sector should continue to grow over the next decade due to an increase in tourism, which serves as the backbone of the food service sector throughout Taiwan. This increase can also be attributed to several other factors as well, including the rise in consumer income, smaller family size, increasing numbers of working women and the development of web marketing. Post: Commodities: Taipei ATO SECTION I. MARKET SUMMARY Macro-economic Situation Although it is a small island (about the size of Maryland and Delaware combined) with a population of only 23.5 million people, Taiwan has developed into one of the world's largest economic and trading entities. Over the past decade, Taiwan has transformed itself from a light industry-manufacturing base to a global center for the production of high technology products. With a nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of $529.6 billion in 2014, Taiwan is the world's 21st largest economy, as well as the 6th largest economy in Asia. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMl films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. These are also available as one exposure on a standard 35mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Com pany 300 Nortfi Z eeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9011202 Middle Mandarin phonology: A study based on Korean data Kim, Yoimgman, Ph.D.