Download PDF 'Evolutionary Diversification of the Flowers in Angiosperms'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Santalales (Including Mistletoes)"

Santalales (Including Introductory article Mistletoes) Article Contents . Introduction Daniel L Nickrent, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois, USA . Taxonomy and Phylogenetics . Morphology, Life Cycle and Ecology . Biogeography of Mistletoes . Importance of Mistletoes Online posting date: 15th March 2011 Mistletoes are flowering plants in the sandalwood order that produce some of their own sugars via photosynthesis (Santalales) that parasitise tree branches. They evolved to holoparasites that do not photosynthesise. Holopar- five separate times in the order and are today represented asites are thus totally dependent on their host plant for by 88 genera and nearly 1600 species. Loranthaceae nutrients. Up until recently, all members of Santalales were considered hemiparasites. Molecular phylogenetic ana- (c. 1000 species) and Viscaceae (550 species) have the lyses have shown that the holoparasite family Balano- highest species diversity. In South America Misodendrum phoraceae is part of this order (Nickrent et al., 2005; (a parasite of Nothofagus) is the first to have evolved Barkman et al., 2007), however, its relationship to other the mistletoe habit ca. 80 million years ago. The family families is yet to be determined. See also: Nutrient Amphorogynaceae is of interest because some of its Acquisition, Assimilation and Utilization; Parasitism: the members are transitional between root and stem para- Variety of Parasites sites. Many mistletoes have developed mutualistic rela- The sandalwood order is of interest from the standpoint tionships with birds that act as both pollinators and seed of the evolution of parasitism because three early diverging dispersers. Although some mistletoes are serious patho- families (comprising 12 genera and 58 species) are auto- gens of forest and commercial trees (e.g. -

Seed Ecology Iii

SEED ECOLOGY III The Third International Society for Seed Science Meeting on Seeds and the Environment “Seeds and Change” Conference Proceedings June 20 to June 24, 2010 Salt Lake City, Utah, USA Editors: R. Pendleton, S. Meyer, B. Schultz Proceedings of the Seed Ecology III Conference Preface Extended abstracts included in this proceedings will be made available online. Enquiries and requests for hardcopies of this volume should be sent to: Dr. Rosemary Pendleton USFS Rocky Mountain Research Station Albuquerque Forestry Sciences Laboratory 333 Broadway SE Suite 115 Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA 87102-3497 The extended abstracts in this proceedings were edited for clarity. Seed Ecology III logo designed by Bitsy Schultz. i June 2010, Salt Lake City, Utah Proceedings of the Seed Ecology III Conference Table of Contents Germination Ecology of Dry Sandy Grassland Species along a pH-Gradient Simulated by Different Aluminium Concentrations.....................................................................................................................1 M Abedi, M Bartelheimer, Ralph Krall and Peter Poschlod Induction and Release of Secondary Dormancy under Field Conditions in Bromus tectorum.......................2 PS Allen, SE Meyer, and K Foote Seedling Production for Purposes of Biodiversity Restoration in the Brazilian Cerrado Region Can Be Greatly Enhanced by Seed Pretreatments Derived from Seed Technology......................................................4 S Anese, GCM Soares, ACB Matos, DAB Pinto, EAA da Silva, and HWM Hilhorst -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

The Flora of Guadalupe Island, Mexico

qQ 11 C17X NH THE FLORA OF GUADALUPE ISLAND, MEXICO By Reid Moran Published by the California Academy of Sciences San Francisco, California Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences, Number 19 The pride of Guadalupe Island, the endemic Cisfuiillw giiailulupensis. flowering on a small islet off the southwest coast, with cliffs of the main island as a background; 19 April 1957. This plant is rare on the main island, surviving only on cliffs out of reach of goats, but common here on sjoatless Islote Nccro. THE FLORA OF GUADALUPE ISLAND, MEXICO Q ^ THE FLORA OF GUADALUPE ISLAND, MEXICO By Reid Moran y Published by the California Academy of Sciences San Francisco, California Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences, Number 19 San Francisco July 26, 1996 SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE: Alan E. Lcviton. Ediinr Katie Martin, Managing Editor Thomas F. Daniel Michael Ghiselin Robert C. Diewes Wojciech .1. Pulawski Adam Schift" Gary C. Williams © 1906 by the California Academy of Sciences, Golden (iate Park. San Francisco, California 94118 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any infcMination storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 96-084362 ISBN 0-940228-40-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract vii Resumen viii Introduction 1 Guadalupe Island Description I Place names 9 Climate 13 History 15 Other Biota 15 The Vascular Plants Native -

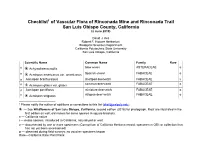

Rinconada Checklist-02Jun19

Checklist1 of Vascular Flora of Rinconada Mine and Rinconada Trail San Luis Obispo County, California (2 June 2019) David J. Keil Robert F. Hoover Herbarium Biological Sciences Department California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n ❀ Achyrachaena mollis blow wives ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon americanus var. americanus Spanish-clover FABACEAE o n Acmispon brachycarpus shortpod deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acmispon glaber var. glaber common deerweed FABACEAE o n Acmispon parviflorus miniature deervetch FABACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon strigosus strigose deer-vetch FABACEAE o 1 Please notify the author of additions or corrections to this list ([email protected]). ❀ — See Wildflowers of San Luis Obispo, California, second edition (2018) for photograph. Most are illustrated in the first edition as well; old names for some species in square brackets. n — California native i — exotic species, introduced to California, naturalized or waif. v — documented by one or more specimens (Consortium of California Herbaria record; specimen in OBI; or collection that has not yet been accessioned) o — observed during field surveys; no voucher specimen known Rare—California Rare Plant Rank Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n Acmispon wrangelianus California deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acourtia microcephala sacapelote ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Adelinia grandis Pacific hound's tongue BORAGINACEAE v n ❀ Adenostoma fasciculatum var. chamise ROSACEAE o fasciculatum n Adiantum jordanii California maidenhair fern PTERIDACEAE o n Agastache urticifolia nettle-leaved horsemint LAMIACEAE v n ❀ Agoseris grandiflora var. grandiflora large-flowered mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. cryptopleura annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. heterophylla annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE o i Aira caryophyllea silver hairgrass POACEAE o n Allium fimbriatum var. -

A Case Study Based on the Wondrous Order Plants Table

Highly competitive – he has to be in first place, it is very important to him, to be number one – with his siblings in particu- A Case Study Based lar, even though he is younger than they are. When his siblings fight he tells them – he is friends with both of them. On the one on the Wondrous hand he competes with them and on the other, it is highly important that everyone likes him. Should one brother tell him, “I Order Plants Table am not your friend”–he wants to die. This really threatens him. It is highly important Michal Yakir, Israel that they will not be angry with him. If I am angry with him – he is worried about it, from a young age”. Case of a Child Suffering cool and gets along with everything. He He is short for his age. has no anxieties during day-to-day life. He MATERIA MEDICA AND CASES from Ear Infections was always a calm child, and this is why I Cravings: Sweets (3) especially lollipops, decided to have yet another baby… but purple, pink and red ones. He likes to eat This is a case study of a four-year-old child, perhaps, something which is suppressed chocolate and cheese. Otherwise he is not arriving with his mother for a first consul- during the day surfaces at night? During much of an eater. tation on 28.4.10. the day he is calm, but a medium we con- sulted suggested his anxieties are related He is not fond of tomatoes (recently) and Observation: a delicate looking child, with with a past life. -

European Academic Research

EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARCH Vol. IV, Issue 10/ January 2017 Impact Factor: 3.4546 (UIF) ISSN 2286-4822 DRJI Value: 5.9 (B+) www.euacademic.org Evidences from morphological investigations supporting APGIII and APGIV Classification of the family Apocynaceae Juss., nom. cons IKRAM MADANI Department of Botany, Faculty of Science University of Khartoum, Sudan LAYALY IBRAHIM ALI Faculty of Science, University Shandi EL BUSHRA EL SHEIKH EL NUR Department of Botany, Faculty of Science University of Khartoum, Sudan Abstract: Apocynaceae have traditionally been divided into into two subfamilies, the Plumerioideae and the Apocynoideae. Recently, based on molecular data, classification of Apocynaceae has undergone considerable revisions. According to the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group III (APGIII, 2009), and the update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group APG (APGIV, 2016) the family Asclepiadaceae is now included in the Apocynaceae. The family, as currently recognized, includes some 1500 species divided in about 424 genera and five subfamilies: Apocynoideae, Rauvolfioideae, Asclepiadoideae, Periplocoideae, and Secamonoideae. In this research selected species from the previous families Asclepiadaceae and Apocynaceae were morphologically investigated in an attempt to distinguish morphological important characters supporting their new molecular classification. 40 morphological characters were treated as variables and analyzed for cluster of average linkage between groups using the statistical package SPSS 16.0. Resulting dendrograms confirm the relationships between species from the previous families on the basis of their flowers, fruits, 8259 Ikram Madani, Layaly Ibrahim Ali, El Bushra El Sheikh El Nur- Evidences from morphological investigations supporting APGIII and APGIV. Classification of the family Apocynaceae Juss., nom. cons and seeds morphology. Close relationships were reported between species from the same subfamilies. -

Phylogenomic Approach

Toward the ultimate phylogeny of Magnoliaceae: phylogenomic approach Sangtae Kim*1, Suhyeon Park1, and Jongsun Park2 1 Sungshin University, Korea 2 InfoBoss Co., Korea Mr. Carl Ferris Miller Founder of Chollipo Arboretum in Korea Chollipo Arboretum Famous for its magnolia collection 2020. Annual Meeting of Magnolia Society International Cholliop Arboretum in Korea. April 13th~22th, 2020 http://WWW.Chollipo.org Sungshin University, Seoul, Korea Dr. Hans Nooteboom Dr. Liu Yu-Hu Twenty-one years ago... in 1998 The 1st International Symposium on the Family Magnoliaceae, Gwangzhow Dr. Hiroshi Azuma Mr. Richard Figlar Dr. Hans Nooteboom Dr. Qing-wen Zeng Dr. Weibang Sun Handsome young boy Dr. Yong-kang Sima Dr. Yu-wu Law Presented ITS study on Magnoliaceae - never published Ten years ago... in 2009 Presented nine cp genome region study (9.2 kbp) on Magnoliaceae – published in 2013 2015 1st International Sympodium on Neotropical Magnoliaceae Gadalajara, 2019 3rd International Sympodium and Workshop on Neotropical Magnoliaceae Asterales Dipsacales Apiales Why magnolia study is Aquifoliales Campanulids (Euasterids II) Garryales Gentianales Laminales Solanales Lamiids important in botany? Ericales Asterids (Euasterids I) Cornales Sapindales Malvales Brassicales Malvids Fagales (Eurosids II) • As a member of early-diverging Cucurbitales Rosales Fabales Zygophyllales Celestrales Fabids (Eurosid I) angiosperms, reconstruction of the Oxalidales Malpighiales Vitales Geraniales Myrtales Rosids phylogeny of Magnoliaceae will Saxifragales Caryphyllales -

Full of Beans: a Study on the Alignment of Two Flowering Plants Classification Systems

Full of beans: a study on the alignment of two flowering plants classification systems Yi-Yun Cheng and Bertram Ludäscher School of Information Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA {yiyunyc2,ludaesch}@illinois.edu Abstract. Advancements in technologies such as DNA analysis have given rise to new ways in organizing organisms in biodiversity classification systems. In this paper, we examine the feasibility of aligning two classification systems for flowering plants using a logic-based, Region Connection Calculus (RCC-5) ap- proach. The older “Cronquist system” (1981) classifies plants using their mor- phological features, while the more recent Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV (APG IV) (2016) system classifies based on many new methods including ge- nome-level analysis. In our approach, we align pairwise concepts X and Y from two taxonomies using five basic set relations: congruence (X=Y), inclusion (X>Y), inverse inclusion (X<Y), overlap (X><Y), and disjointness (X!Y). With some of the RCC-5 relationships among the Fabaceae family (beans family) and the Sapindaceae family (maple family) uncertain, we anticipate that the merging of the two classification systems will lead to numerous merged solutions, so- called possible worlds. Our research demonstrates how logic-based alignment with ambiguities can lead to multiple merged solutions, which would not have been feasible when aligning taxonomies, classifications, or other knowledge or- ganization systems (KOS) manually. We believe that this work can introduce a novel approach for aligning KOS, where merged possible worlds can serve as a minimum viable product for engaging domain experts in the loop. Keywords: taxonomy alignment, KOS alignment, interoperability 1 Introduction With the advent of large-scale technologies and datasets, it has become increasingly difficult to organize information using a stable unitary classification scheme over time. -

Santalales: Opiliaceae) in Taiwan

Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e51544 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.8.e51544 Taxonomic Paper First report of the root parasite Cansjera rheedei (Santalales: Opiliaceae) in Taiwan Po-Hao Chen‡, An-Ching Chung§, Sheng-Zehn Yang| ‡ Graduate Institute of Bioresources, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, Neipu Township, Pintung, Taiwan § Liouguei Research Center, Taiwan Forest Research Institute, Liouguei District, Kaohsiung, Taiwan | Department of Forestry, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, Neipu Township, Pintung, Taiwan Corresponding author: Sheng-Zehn Yang ([email protected]) Academic editor: Yasen Mutafchiev Received: 27 Feb 2020 | Accepted: 08 Apr 2020 | Published: 10 Apr 2020 Citation: Chen P-H, Chung A-C, Yang S-Z (2020) First report of the root parasite Cansjera rheedei (Santalales: Opiliaceae) in Taiwan. Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e51544. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.8.e51544 Abstract Background The family Opiliaceae in Santalales comprises approximately 38 species within 12 genera distributed worldwide. In Taiwan, only one species of the tribe Champereieae, Champereia manillana, has been recorded. Here we report the first record of a second member of Opiliaceae, Cansjera in tribe Opilieae, for Taiwan. New information The newly-found species, Cansjera rheedei J.F. Gmelin (Opiliaceae), is a liana distributed from India and Nepal to southern China and western Malaysia. This is the first record of both the genus Cansjera and the tribe Opilieae of Opiliaceae in Taiwan. In this report, we provide a taxonomic description for the species and colour photographs to facilitate identification in the field. © Chen P et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Rich Zingiberales

RESEARCH ARTICLE INVITED SPECIAL ARTICLE For the Special Issue: The Tree of Death: The Role of Fossils in Resolving the Overall Pattern of Plant Phylogeny Building the monocot tree of death: Progress and challenges emerging from the macrofossil- rich Zingiberales Selena Y. Smith1,2,4,6 , William J. D. Iles1,3 , John C. Benedict1,4, and Chelsea D. Specht5 Manuscript received 1 November 2017; revision accepted 2 May PREMISE OF THE STUDY: Inclusion of fossils in phylogenetic analyses is necessary in order 2018. to construct a comprehensive “tree of death” and elucidate evolutionary history of taxa; 1 Department of Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of however, such incorporation of fossils in phylogenetic reconstruction is dependent on the Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA availability and interpretation of extensive morphological data. Here, the Zingiberales, whose 2 Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, familial relationships have been difficult to resolve with high support, are used as a case study MI 48109, USA to illustrate the importance of including fossil taxa in systematic studies. 3 Department of Integrative Biology and the University and Jepson Herbaria, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA METHODS: Eight fossil taxa and 43 extant Zingiberales were coded for 39 morphological seed 4 Program in the Environment, University of Michigan, Ann characters, and these data were concatenated with previously published molecular sequence Arbor, MI 48109, USA data for analysis in the program MrBayes. 5 School of Integrative Plant Sciences, Section of Plant Biology and the Bailey Hortorium, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA KEY RESULTS: Ensete oregonense is confirmed to be part of Musaceae, and the other 6 Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) seven fossils group with Zingiberaceae. -

Systematics, Climate, and Ecology of Fossil and Extant Nyssa (Nyssaceae, Cornales) and Implications of Nyssa Grayensis Sp

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2013 Systematics, Climate, and Ecology of Fossil and Extant Nyssa (Nyssaceae, Cornales) and Implications of Nyssa grayensis sp. nov. from the Gray Fossil Site, Northeast Tennessee Nathan R. Noll East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Climate Commons, Paleontology Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Noll, Nathan R., "Systematics, Climate, and Ecology of Fossil and Extant Nyssa (Nyssaceae, Cornales) and Implications of Nyssa grayensis sp. nov. from the Gray Fossil Site, Northeast Tennessee" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1204. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1204 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Systematics, Climate, and Ecology of Fossil and Extant Nyssa (Nyssaceae, Cornales) and Implications of Nyssa grayensis sp. nov. from the Gray Fossil Site, Northeast Tennessee ___________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Biological Sciences East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Biology ___________________________ by Nathan R. Noll August 2013 ___________________________ Dr. Yu-Sheng (Christopher) Liu, Chair Dr. Tim McDowell Dr. Foster Levy Keywords: Nyssa, Endocarp, Gray Fossil Site, Miocene, Pliocene, Karst ABSTRACT Systematics, Climate, and Ecology of Fossil and Extant Nyssa (Nyssaceae, Cornales) and Implications of Nyssa grayensis sp.