1 UNCORRECTED PROOF Palestinian Political Forgiveness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irena Dahl Master's Thesis in Middle East Studies

Election Dilemmas: Palestinian Engagement in Jerusalem Municipal Elections Irena Dahl Master’s Thesis in Middle East Studies (MES4590) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages 30 credits UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2020 i © Irena Dahl 2020 Election Dilemmas: Palestinian Engagement in Jerusalem Mu- nicipal Elections of 2018 Irena Dahl http://www.duo.uio.no/ ii Abstract Since the occupation until the present day, there have been great disparities in service provision be- tween the West and East Jerusalem. Even though East Jerusalemites have the status of permanent residents in Israel and are entitled welfare and municipal services, only as little as 10% of the mu- nicipal budget is allocated to East Jerusalem. There is a shortage of services such as water, sewage, road maintenance and garbage collection. The schools in East Jerusalem are in deplorable condition and there is a lack of classrooms and qualified staff. Some claim that the neglect is caused by Pales- tinians’ non-participation in the municipal elections. Palestinians in East Jerusalem have tradition- ally been boycotting the municipal elections in Jerusalem since the annexation in 1967. The reason for the boycott stems from recognizing the legitimacy of the Jerusalem municipality and Israel’s control over East Jerusalem. Thus, the PLO and religious leaders encourage East Jerusalemites not to vote in the elections. However, in 2018 there was an unprecedented interest in the elections among Palestinians. Two Palestinian candidates intended to enter the electoral race, albeit only one ran for the council seat. This thesis seeks to examine how Palestinian engagement in the elections has changed throughout the years by looking at historical timeline, analyzing Palestinians’ pro and contra elections arguments and discussing Israel’s policies towards East Jerusalem residents. -

Introducing MEPI

MEPI MIDDLE EAST PEACE INITIATIVE UNIVERSAL PEACE FEDERATION Introducing MEPI The Middle East Peace Initiative (MEPI) is a key strategic Those who act according to their conscience and work project of the Universal Peace Federation. It began in for the wellbeing of others are in accordance with 2003 as a Track II diplomacy effort bringing a wide universal spiritual principles. range of religious perspectives into the center of the What will be the impact of our peace programs and search for peace. More than 12,000 people have service projects? The civil rights marches led by Dr. participated in MEPI programs in Israel, the Palestinian Martin Luther King, Jr., raised people’s consciousness Territories, Jordan, and Lebanon. about racism and changed a nation. Mahatma Gandhi MEPI brings compassionate and spiritually-motivated led a movement that accomplished the seemingly impos- people to a shared vision of humanity as “One Family sible task of overcoming an empire. Nelson Mandela Under God.” We seek interreligious cooperation and kept the dream of peaceful reconciliation alive during constructive relationships among religions, governments, twenty-seven years in prison and led his people to a and civil society. Reconciling the family of Abraham is peaceful transition of power. our focus, and we bring that spirit to elected officials and Yes, to make peace in the Middle East takes time. But the other community leaders. This can stimulate new partner- seeds are being sown as people and families change, ships in peacebuilding and better public policies. one at a time. Our concept of spiritual leadership is broad. Everyone has a conscience that guides them to work for peace. -

Rescuing Israeli-Palestinian Peace the Fathom Essays 2016-2020

Rescuing Israeli-Palestinian Peace The Fathom Essays 2016-2020 DENNIS ROSS DAHLIA SCHEINDLIN HUSAM ZOMLOT SARAI AHARONI HUDA ABU ARQOUB TIZRA KELMAN HUSSEIN AGHA ALI ABU AWAD KHALED ELGINDY AMOS GILEAD YAIR HIRSCHFELD JOEL SINGER EINAT WILF YOSSI KLEIN HALEVI ZIAD DARWISH YOSSI KUPERWASSER ORNA MIZRAHI TOBY GREENE KOBY HUBERMAN SETH ANZISKA LAUREN MELLINGER SARA HIRSCHHORN ALEX RYVCHIN GRANT RUMLEY MOHAMMED DAJANI MICHAEL HERZOG AMIR TIBON DORE GOLD TONY KLUG ILAN GOLDENBERG JOHN LYNDON AZIZ ABU SARAH MEIR KRAUSS AYMAN ODEH MICAH GOODMAN SHANY MOR CALEV BEN-DOR SHALOM LIPNER DAVID MAKOVSKY ASHER SUSSER GILEAD SHER NED LAZARUS MICHAEL KOPLOW MICHAEL MELCHIOR ORNI PETRUSHKA NAFTALI BENNETT KRIS BAUMAN ODED HAKLAI JACK OMER-JACKAMAN DORON MATZA GERSHON HACOHEN SHAUL JUDELMAN NAVA SONNENSCHEIN NOAM SCHUSTER-ELIASSI Edited by Alan Johnson, Calev Ben-Dor and Samuel Nurding 1 ENDORSEMENTS For those convinced of the continuing relevance to global peace and security of a resolution to the issues between the Palestinian people and Israel, Fathom provides an invaluable and widely drawn set of essays at just the right time. With a focus and interest recently enhanced by dramatic and significant events, these differing points of view and suggestions for progress make a great and thoughtful contribution. Rt Hon Alistair Burt, UK Minister for the Middle East and North Africa 2010-13, and 2017-19; Distinguished Fellow, RUSI Israelis and Palestinians are not going anywhere and neither can wish the other away. That, alone, makes a powerful argument for a two states for two peoples outcome to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In Rescuing Israeli-Palestinian Peace 2016-2020, one can read 60 essays looking at every aspect of two states and how they might be achieved. -

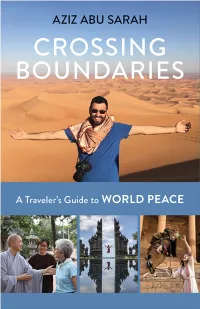

A Miraculous Mix in Bethany Grace Lutheran Church of Evanston Aziz Abu Sarah, a Palestinian I Played Anything

www.graceevanston.org • [email protected] Fall Winter 2019 Affirming, Courageous, Caring A Miraculous Mix in Bethany Grace Lutheran Church of Evanston Aziz Abu Sarah, a Palestinian I played anything. I said, ‘Yes, 1430 South Blvd. growing up in the occupied a bit of guitar.’ ‘Then you must 847.475.2211 territory of east Jerusalem, play something!’ exclaimed lost his brother Tayseer after Anna, the Jewish lead singer. I Grace Is An Open And Affirming RIC he was arrested and beaten began to play, ‘Kiss,’ by Prince, Congregation by the Israeli Defense Forces. and the whole group excited- Tayseer was caught throwing ly joined in. Marwan, the Pal- OUR MISSION: stones, to which he refused to estinian lute player, told me To courageously confess. After his release, Tay- they would invite me up to live out our faith by seer died at the age of 19 due play it at the end of their set. sharing grace with to the effects of his internal injuries from beatings dur- After the band set up to play, our group was invited to each other and the ing his arrest. Aziz was ten years old at the time. It took the dance floor. We were entertained by Aziz’ young communities we serve. many years of challenging and reconciling relation- nephews as we circle-danced ecstatically in both Pal- OUR VISION: ships, but out of Aziz’ pain and anger something mi- estinian and Israeli styles. The Middle Way played a All God’s people raculous was birthed: a peace-building travel philoso- mixture of soulful and energetic Israeli and Palestin- will feel accepted, phy known as ‘dual-narrative’ tourism. -

Crossing Boundaries

Praise for Crossing Boundaries “Aziz Abu Sarah articulates something I have long believed about travel: that it has the potential to help heal and regenerate the planet not just by protecting nature and cultures but also by promoting un- derstanding and peace. And he rightly reminds us that it’s not more travel we should be after but the right kind of travel—one that treads lightly, highlights multiple perspectives (including traditionally mar- ginalized ones), and fosters personal transformation, which is the key to a better world.” —Norie Quintos, independent tourism consultant and Editor at Large, National Geographic Travel Media “Crossing Boundaries reminds us that travel at its best is so much more than selfies and Instagram moments. It is breaking bread and sharing exotic flavors, powerful conversations, and transformational experiences with strangers who quickly become friends and some- times even family. Whether we’re on a trip across town or an expedi- tion halfway around the world . history, art, food, religion, and politics mean very little without human connection and real conver- sation. Aziz Abu Sarah is a guide in the truest sense of the word, ushering in the powerful new age of experiential travel. Read Cross- ing Boundaries and get off the beaten path to discover your own humanity. Let the adventure begin.” —Mark Bauman, former Senior Vice President, Smithsonian Media “Crossing Boundaries is essential reading for any budding traveler. For an inexperienced traveler, it’s a great handbook of how to navigate your way around the world—from avoiding overtourism hotspots to ensuring you are meeting and interacting with local people during your journey. -

The Palestinain Boycott of Israeli Municipal Elections in Jerusalem

34 THE PALESTINIAN BOYCOTT OF ISRAELI MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS IN JERUSALEM: POLITICS OF IDENTITY, LEGITIMACY, AND CIVIL RESISTANCE Ieva Gailiunaite Electoral boycotts are a form of civil resistance rooted in the refusal to accept the political status quo, and this is particularly notable in the East Jerusalem Palestinian boycott of Israeli municipal elections since 1967. The municipal boycott in Jerusalem has been stud- ied as a part of wider analyses of Palestinian resistance to Israeli occupation. The situation has been presented to be a result of passivity, disillusionment, and path dependency, or depicting East Jerusalemite Palestinians as the hostages of the political impasse within the region. This dissertation argues for the centrality of the boycott as a long-term movement that reinforces Palestinian identity, legitimacy, and agency within Jerusalem. It demon- strates that long-term identity-based factors are more important than short-term civil and material ones. Concepts of a Palestinian East Jerusalemite identity within a divided city show the importance of the boycott in maintaining agency within the city, without legit- imising Israeli occupation. The role of pressure from political actors on both the Palestin- ian and Israeli sides is evaluated in their influence on the boycott. The steadfastness of the boycott by a third of the voting population in Jerusalem demonstrates the importance of the city’s Palestinian inhabitants and their active role from the heart of the issue within the wider scope of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. SECTION ONE: INTRODUCTION AND METHOD INTRODUCTION The city of Jerusalem is a unique place where thousands of years of history, religion, and politics have intertwined and often clashed. -

Arab Citizen Perspectives on Annexation: Leadership, Civil Society and Public Discourse August 2020

Inter-Agency Task Force on Israeli Arab issues Arab Citizen Perspectives on Annexation: Leadership, Civil Society and Public Discourse August 2020 In September 2019, in the lead-up to Israel’s second general elections, PM Netanyahu announced intentions to annex parts of the West Bank and later made this a top and even urgent priority of the new unity government, formed in May 2020. While no action has been taken thus far and the parameters of possible annexation remain unclear, the declaration has generated strong responses within and outside of Israel, mostly in the context of its anticipated impact on the two- state solution, the viability of Palestinian statehood, relations with the wider Arab world and Israel’s standing in the international community. In the ensuing controversy, less focus has been placed on the potential impact on and perspectives of the Arab minority living within Israel. Arab citizens of Israel comprise almost one- fifth of Israel’s population, approximately 1.6 million people.1 At once part of Israel’s national fabric as citizens living, studying, working and voting in the country, Arabs inside Israel also share a strong sense of identity and peoplehood with--and concerns for—Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza. In some circles, Arab citizens of Israel envision serving as a bridge between the populations. Arab public discourse in Israel is quite consistently opposed to the proposed annexation. This view is reinforced by a June survey by aChord Center, which found that 92% of Arab polled oppose annexation, and a May poll by the Israel Democracy Institute which showed only 8.8% of Arab respondents in support. -

What Might Happen If Palestinians Start Voting in Jerusalem Municipal Elections? Gaming the End of the Electoral Boycott and the Future of City Politics

What Might Happen if Palestinians Start Voting in Jerusalem Municipal Elections? Gaming the End of the Electoral Boycott and the Future of City Politics Jonathan Blake, Elizabeth M. Bartels, Shira Efron, Yitzhak Reiter C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2743 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0173-1 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2018 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: Ya'ara Issar, Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Since Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem after the 1967 war, the vast majority of Palestinian residents of the city have boycotted participation in municipal elections to avoid legitimating Israeli rule. -

The Case for the One-State Solution with the Two-State Solution on Life Support, It’S Time to Revisit Solutions Once Discarded As Radical—Namely, the One-State Option

The Case for the One-State Solution With the two-state solution on life support, it’s time to revisit solutions once discarded as radical—namely, the one-state option By Abdel Monem Said Aly f a two-state solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict is unreachable, it is time to consider alternatives. The one-state option seems to be the I frontrunner, competing only with the continuation of the untenable status quo. The idea is already on the table in Arab and Israeli circles, and open to debate. Today it appears as the only workable alternative to the two-state solution, which has prevailed since the partition resolution of 1947. There is no sign of an implementation of the two-state solution on the horizon, and if it were attempted, it would resemble a surgical operation with a great deal of blood loss. While there are voices on both sides—Israeli and Palestinian—that continue to argue for a single state from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean, under either Israeli or Palestinian control, their claims are unrealistic. They cannot account for what would happen to the population of the other side. Reality has given rise to the idea of a single state for both the Palestinian and the Israeli peoples. According to opinion polls, there is a minority on both sides that supports this idea. Most are young people who hope to see a solution in some foreseeable future and avoid the years of conflict their parents and grandparents lived through. History of an Idea For seven decades, the equations of the Arab–Israeli conflict have revolved around two variables: the creation of realities on the ground and political, diplomatic, and military prowess. -

Another Story Heard a Bibliography of Resources About Palestinians For

Another Story Heard A Bibliography of Resources About Palestinians For Children and Youth April 2019 1 Table of Contents Introduction p. 3 How to Use this Bibliography p. 5 Books p. 7 Elementary School p. 7 Middle School p. 11 High School p. 14 Graphic/Cartoon Novels p. 20 Poetry p. 22 Curriculum p. 23 Elementary/Middle School p. 23 Middle/High School p. 24 Kindergarten through High School p. 28 Films/Videos p. 30 Elementary/Middle School p. 31 Middle/High School p. 32 Additional Resources p. 37 Commentary/Next Steps p. 39 Acknowledgments p. 40 2 Introduction The Bibliography is intended to expand our points of view on the lives and experiences of Palestinians in Israel/Palestine post-1948 among children and youth. Stories about Palestinians have not been heard or studied often in classrooms, churches, synagogues, and community settings in the United States. It is our hope that this Bibliography will contribute to the growing movement to challenge those omissions. The compilation has depended on volunteers who gathered materials and then offered their insights on each resource. As they did their work, a few of these volunteers shared some insights on their own experiences with unheard stories: • I remember enrolling in a “World History or Literature” course only to find, in retrospect, that the course wasn’t about the world, but was really focused on Europe and excluded places like South America, Africa or Asia. • I took a variety of music courses in middle and high school and only later realized that all the composers we studied were men! • I grew up in the South and am horrified to say that I never learned about lynchings in the South from any of the American history books we used. -

IAAP Bulletin the International Association of Applied Psychology Covering the World of Applied Psychology

Issue 23: 1-2 January/April, 2011 The IAAP Bulletin The International Association of Applied Psychology Covering the World of Applied Psychology Plus: Valerie’s Editorial The President’s Corner Robert Morgan’s Commentary Division News UN Trivia Editors: Valerie Hearn, USA Dennis R Trent, UK Email for submissions: [email protected] The President’s Corner Happy New Year, IAAP friends. I hope 2010 was a good year for you and that you have had some time to relax and are ready for the new year. In my first presidential column, published in the October Bulletin, I described my history of involvement in psychological associations, first at the state level, then regional, then national and, increasingly, international. Psychological associations have been an important part of my professional and personal life, and I have tremendous respect for the importance of psychological associations and what they can do for psychology and for psychologists. One of the most important functions of IAAP is to sponsor, every four years, the International Congress of Applied Psychology (ICAP). The most recent ICAP, held in Melbourne, Australia in July 2010, was highly successful. Despite being held in a time of economic stress and in a continent far from most other continents, it attracted 3,300 participants from 74 countries, and its scientific program was of the highest quality. Returning from Australia, I reflected on how important international congresses have been over the years in bringing world psychologists together to share information and also in creating new associations which, in turn, sponsor more congresses. Unlike some other species, human beings are social animals. -

What Might Happen If Palestinians Start Voting in Jerusalem Municipal Elections? Gaming the End of the Electoral Boycott and the Future of City Politics

What Might Happen if Palestinians Start Voting in Jerusalem Municipal Elections? Gaming the End of the Electoral Boycott and the Future of City Politics Jonathan Blake, Elizabeth M. Bartels, Shira Efron, Yitzhak Reiter C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2743 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0173-1 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2018 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: Ya'ara Issar, Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Since Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem after the 1967 war, the vast majority of Palestinian residents of the city have boycotted participation in municipal elections to avoid legitimating Israeli rule.