1 | Page History of Dune Management in the NPS Assigned Area Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HIKING TRAILS SOUTH SUNSHINE COAST Sunshinecoastcanada.Com

HIKING TRAILS SOUTH SUNSHINE COAST sunshinecoastcanada.com Local Favourites ROBERTS CREEK heritage graveyard on the Sechelt First Nations band land at the east end. CLIFF GILKER PARK TRAILS ACCESS: From Highway 101 in Sechelt, access the walk- LENGTH & DIFFICULTY: 7 km of trails | 15 min to 2.5 hrs | way from Shorncliffe, Ocean, Trail, Inlet, or Wharf Avenues. GIBSONS Moderate Trails are colour coded and easy to follow and all loop back BURNETT FALLS GIBSONS SEAWALL to the parking lot. The park is a largely advanced second LENGTH & DIFFICULTY: 10-15 min one way | Very Easy LENGTH & DIFFICULTY: 20-30 min one way | Easy growth Douglas Fir forest. Roberts Creek and Clack Creek A short walk with a bit of an incline that ends at a spectacular Paved waterfront walkway with views of Gibsons Marina, flow through this park. The trails cross them at various view of the waterfall. points on rustic wooden bridges and the waterfall is a high- Gibsons Harbour, Keats Island and North Shore moun- ACCESS: 5396 Burnett Rd. From Sechelt, go north on light (especially in the winter time). Wheelchair accessible tains. Just steps away from shops and restaurants in Lower Wharf Ave. At the 4-way stop, turn right onto East Porpoise viewing platform. Gibsons. Bay Rd. Take a right turn on Burnett Rd. and park at the end. ACCESS: There are access points along Marine Drive and ACCESS: Follow Hwy 101 west from Gibsons for 10 km or Trailhead will be visible. Gower Point Road in Gibsons, including Armours Beach, drive east on Hwy 101 from Sechelt. -

Coastal Land Loss and Wktlanb Restoration

COASTAL LAND LOSS AND WKTLANB RESTORATION tSI R. E. Turner estuaryare causallyrelated to the landlosses this sealevel ri se,climate change~, soil type,geomorphic century." I then comparethe strengthof this frameworkand age, subsidence or tnanagement. hypothesisto someof theother hypothesized causes of land loss on this coast, There are laboratoryand Four Hypotheses small-scale field trials that support various hypotheses,It seemsto me thatthe mostreliable Four hypothesesabout the causes of indirect interpretationsare basedon what happensin the wetlandlosses in BaratariaBay will be addressed field, andnot on the resultsof computermodels, here adapted from Turner 1997!: laboratorystudies or conceptualdiagrams. H l. i ct n ences of The test results discussed herein are derived t !tin oil banks v d solelyfrom data derived at a landscapescale. The 'ori of 1 loss sin h data set is restricted to a discussion of the Barataria watershed. This watershed is a significant H2. componentof theLouisiana coastal zorie 14,000 lv ha!and there are a varietyof habitatdata available i tl on it. Its easternboundary is the MississippiRiver from whichoccasional overflowing waters are v n.vi hypothesizedto deliver enoughsediinents and on 1 v tno I freshwaterto significantlyinfluence the balanceof rit f i land lossor gain in the receivingwatershed, and whosere-introduction would restore the estuary's wetlands. Improvingour understandingof the H4. w rin si ecologicalprocesses operating in this watershed h ' ' of mightassist in the managementof others. The effect of geologicalsubsidence and sea DIrect and Indirect Causes of Wetland Loss level rise are not included in this list because both factorshave remained relatively stablethis century Wetlandloss is essentiallythe same as land loss when the land-loss rates rose and fell, Local on thiscoast Baurnann and Turner 1990!. -

Gulf of California - Sea of Cortez Modern Sailing Expeditions

Gulf of California - Sea of Cortez Modern Sailing Expeditions November 24 to December 4, 2019 Modern Sailing School & Club Cpt Blaine McClish (415) 331 – 8250 Trip Leader THE BOAT — Coho II, 44’ Spencer 1330 Coho II is MSC’s legendary offshore racer/cruiser. She has carried hundreds of MSC students and sailors under the Golden Gate Bridge and onto the Pacific Ocean. At 44.4 feet overall length and 24,000 pounds of displacement, Coho II is built for crossing oceans with speed, seakindly motion, and good performance in both big winds and light airs. • Fast and able bluewater cruiser • Fully equipped for the offshore sailing and cruising experience TRAVEL ARRANGEMENTS You are responsible for booking your own airfare. Direct flights from SFO to La Paz, and Los Cabos to SFO are available but are limited. Flights with layovers in San Diego or Los Angeles will cost less than direct flights. If you would like to use a travel agent to book your flights, we suggest Bob Entwisle at E&E Travel at (415) 819-5665. WHAT TO BRING Luggage Travel light. Your gear should fit in a medium duffel bag and small carry-on bag. Your carry-on should be less than 15 pounds. We recommend using a dry bag or backpack. Both bags should be collapsible for easy storage on the boat in small space. Do not bring bags with hard frames as they are difficult to stow. Gear We have found that people often only use about half of what they bring. A great way to bring only what you use is to lay all your items out and reduce it by 50%. -

Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms

FLORIDA HURRICANES AND TROPICAL STORMS 1871-1995: An Historical Survey Fred Doehring, Iver W. Duedall, and John M. Williams '+wcCopy~~ I~BN 0-912747-08-0 Florida SeaGrant College is supported by award of the Office of Sea Grant, NationalOceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce,grant number NA 36RG-0070, under provisions of the NationalSea Grant College and Programs Act of 1966. This information is published by the Sea Grant Extension Program which functionsas a coinponentof the Florida Cooperative Extension Service, John T. Woeste, Dean, in conducting Cooperative Extensionwork in Agriculture, Home Economics, and Marine Sciences,State of Florida, U.S. Departmentof Agriculture, U.S. Departmentof Commerce, and Boards of County Commissioners, cooperating.Printed and distributed in furtherance af the Actsof Congressof May 8 andJune 14, 1914.The Florida Sea Grant Collegeis an Equal Opportunity-AffirmativeAction employer authorizedto provide research, educational information and other servicesonly to individuals and institutions that function without regardto race,color, sex, age,handicap or nationalorigin. Coverphoto: Hank Brandli & Rob Downey LOANCOPY ONLY Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms 1871-1995: An Historical survey Fred Doehring, Iver W. Duedall, and John M. Williams Division of Marine and Environmental Systems, Florida Institute of Technology Melbourne, FL 32901 Technical Paper - 71 June 1994 $5.00 Copies may be obtained from: Florida Sea Grant College Program University of Florida Building 803 P.O. Box 110409 Gainesville, FL 32611-0409 904-392-2801 II Our friend andcolleague, Fred Doehringpictured below, died on January 5, 1993, before this manuscript was completed. Until his death, Fred had spent the last 18 months painstakingly researchingdata for this book. -

Brief History Timeline 2018 (PDF)

TIMELINE ~ BRIEF HISTORY OF SUGARLOAF COVE, SICA, AND SUGARLOAF: THE NORTH SHORE STEWARDSHIP ASSOCIATION 10,000 P.C. Scattered archeological finds indicate Paleo-Indians occupy the area around Lake Superior’s North Shore after the final retreat of glaciers in the last Ice Age (Pleistocene Epoch). A variety of indigenous peoples inhabit the area over thousands of years. 1600s French explorers have the first contact with indigenous peoples in the area in the early to mid-1600s. Fur trade between native tribes and the French, British, and Dutch flourishes in the 1700s and early 1800s. 1854 The Ojibwe, who were established by then as the primary native tribe in northeastern Minnesota, cede substantially all the Arrowhead region, including Sugarloaf Cove, to the federal government in the Second Treaty of La Pointe, opening the area to European settlement. Settlers, mostly Scandinavian, flock to the North Shore and began commercial fishing and logging operations. 1880s Extensive logging begins in Cook County, including depletion of old growth red and white pine around Sugarloaf Cove. 1899 The John Gunderson family from Norway homesteads Sugarloaf Cove property. 1902 Consolidated Water Power & Paper Company of Wisconsin (“Consolidated”) begins a pulp paper business in Rhinelander (name changed to Consolidated Papers in 1962). 1909 The Superior National Forest is established. 1920s In 1923, Consolidated begins harvesting wood from Canada and rafting pulpwood logs across Lake Superior to Ashland for transport to Rhinelander for processing. In 1925, Consolidated acquires a large tract of timberland in Cook County from which to harvest pulpwood (mostly spruce, jack pine, and balsam fir). -

Poquetanuck Cove Canoe and Kayak Trail Anne T

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Poquetanuck Cove Canoe and Kayak Trail Anne T. Roberts-Pierson Anne T. Poquetanuck Cove – A Very Special Place Poquetanuck Cove is a two mile Beginning in 2008, a three year Phragmites control effort was initiated long tidal estuary located between in Poquetanuck Cove. This effort involved the cooperation of more than the towns of Preston and Ledyard, 20 different entities which included members of the Thames River Basin Connecticut. State Department of Partnership and a variety of funding sources. Phragmites australis is an Energy and Environmental Protection introduced, invasive plant species that had taken root along the fringe areas experts describe the cove as the of the cove’s marsh system. The high quality brackish water marshes of the largest and highest quality brackish cove have been documented to contain plant species rare to Connecticut. water meadow and cattail marsh on the This project would not have been possible without the numerous volunteers Thames River. who participated in gathering important data as part of this effort. For more information about Partnering to Protect Poquetanuck Cove, please visit the An important extension of the Long Thames River Basin Partnership website at www.trbp.org. Island Sound ecosystem, the cove is a State of Connecticut designated bird sanctuary and it provides shelter Royal Oaks Drive, Ledyard: Take Always let friends or family know for significant flocks of wintering Route 2A to Cider Mill Road (Avery where you will put in, take out, and waterfowl each year. Bald eagles are Hill). Then take the second right onto when you expect to return. -

Guillemot Cove Trail

Stavis Bay Road GC01 GC02 Gate GC03 GC04 GC06 GC05 Plateau Loop Trail GC23 GC22 GC07 GC21 GC20 GC19 GC18 GC08 Boyce Creek GC13 0.1 mi GC11 GC09 GC17 GUILLEMOT COVE NATURE RESERVE GC12 GC16 GC10 Stump House GC14 GC15 Copyright OpenStreetMap and contributors, under an open license http://openstreetmap.org Trails Plateau Loop Trail (0.4 mi) Breaks off Guillemot Cove Rules from the upper part of the River Loop The trails in the Guillemot Cove Nature Trail and soon climbs steeply up the ridge 1. Guillemot Cove Nature Reserve has Reserve are all natural surface trails. a “Pack it in – Pack it out” policy. to a plateau in a quiet, open forest. Main Access Trail (0.2 mi.) Begins across Continue around the loop and return the Please bring a bag or other container the road from the parking lot. This trail way you came to the River Loop Trail. for trash and take it when you leave. winds through an evergreen forest with 2. Park in designated areas only. huckleberry underbrush. Watch for dead Beach House Trail (0.25 mi) From the 3. Help protect reserve habitat by snags with Pileated Woodpecker holes. It is kiosk, go across the meadow, cross Boyce staying on trails and off habitat roughly a mile long and sloping downhill. Creek on a wooden bridge and a small areas. One can follow the access road through an footbridge to the hillside. Keep right 4. The reserve, including the beach, is alder and big leaf maple tree forest or across a meadow, by an old orchard, and bordered by private property. -

Nature-Based Coastal Defenses in Southeast Florida Published by Coral Cove Dune Restoration Project

Nature-Based Coastal Defenses Published by in Southeast Florida INTRODUCTION Miami Beach skyline ©Ines Hegedus-Garcia, 2013 ssessments of the world’s metropolitan areas with the most to lose from hurricanes and sea level rise place Asoutheast Florida at the very top of their lists. Much infrastructure and many homes, businesses and natural areas from Key West to the Palm Beaches are already at or near sea level and vulnerable to flooding and erosion from waves and storm surges. The region had 5.6 million residents in 2010–a population greater than that of 30 states–and for many of these people, coastal flooding and erosion are not only anticipated risks of tomorrow’s hurricanes, but a regular consequence of today’s highest tides. Hurricane Sandy approaching the northeast coast of the United States. ©NASA Billions of dollars in property value may be swept away in one storm or slowly eroded by creeping sea level rise. This double threat, coupled with a clearly accelerating rate of sea level rise and predictions of stronger hurricanes and continued population growth in the years ahead, has led to increasing demand for action and willingness on the parts of the public and private sectors to be a part of solutions. Practical people and the government institutions that serve them want to know what those solutions are and what they will cost. Traditional “grey infrastructure” such as seawalls and breakwaters is already common in the region but it is not the only option. Grey infrastructure will always have a place here and in some instances it is the only sensible choice, but it has significant drawbacks. -

FLORIDA HAZARDOUS WEATHER by DAY (To 1994) OCTOBER 1 1969

FLORIDA HAZARDOUS WEATHER BY DAY (to 1994) OCTOBER 1 1969 - 1730 - Clay Co., Orange Park - Lightning killed a construction worker who was working on a bridge. A subtropical storm spawned one weak tornado and several waterspouts in Franklin Co. in the morning. 2 195l - south Florida - The center of a Tropical Storm crossed Florida from near Fort Myers to Vero Beach. Rainfall totals ranged from eight to 13 inches along the track, but no strong winds occurred near the center. The strong winds of 50 to 60 mph were all in squalls along the lower east coast and Keys, causing minor property damage. Greatest damage was from rains that flooded farms and pasture lands over a broad belt extending from Naples, Fort Myers, and Punta Gorda on the west coast to Stuart, Fort Pierce, and Vero Beach on the east. Early fall crops flooded out in rich Okeechobee farming area. Many cattle had to be moved out of flooded area, and quite a few were lost by drowning or starvation. Roadways damaged and several bridges washed out. 2-4 1994 - northwest Florida - Flood/Coastal Flood - The remnants of Tropical Depression 10 moved from the northeast Gulf of Mexico, across the Florida Panhandle, and into Georgia on the 2nd. High winds produced rough seas along west central and northwest Florida coasts causing minor tidal flooding and beach erosion. Eighteen people had to be rescued from sinking boats in the northeast Gulf of Mexico. Heavy rains in the Florida Big Bend and Panhandle accompanied the system causing extensive flooding to roadways, creeks and low lying areas and minor flooding of rivers. -

Downloaded 09/28/21 10:59 AM UTC 1 76 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW Vol

March 1965 Gordon E. Dunn and Staff 175 THEHURRICANE SEASON OF 1964 GORDON E. DUNN AND STAFF* U.S. Weather Bureau Office, Miami, Fla. 1. GENERALSUMMARY spondvery well withthe composite chart for atverage Twelvetropical cyclones,six of hurricaneintensity, departures from nornml for seasons of maxinlum tropical developedover tropical Atlantic waters during 1964. cycloneincidence inthe southeastern United States as This is the largest number since 1955 and compares with developed by Ballenzweig [a]. an average of 10during the past three decades. The September was aneven more active month and cor- centers of four hurricanes penetrated the mainland of the respondence between Ballenzweig'scomposite chrt and United States, the largest number to do so since the five theobserved values was better, particularly south of in 1933. There have been only four other years with four latitude 40' W. According toGreen [3] thesubtropical or more since 1900; four in 1906, 1909, and 1926, and six High was abnornlallystrong and displacedslightly in 1916.While none of thefour renching the mainland northwardfrom normal (favorable for tropical cyclone in 1964 wits :L major hurricane at the time of landfall, formation) while the 700-mb. jet was slightlysouth of three-Cleo, Dora, and EIi1da"were severe. normal (unfavorable). The long-wave position fluctuated Florida was struck by three hurricanes in addition to back and forth from the Rockies and Great Plains east- dyinghurricane Hilda and one tropical cyclone of less ward and the tropical cyclones experienced considerable than hurricane intensity; thus ended an unequalled rela- difficulty in penetrating the westerlies. During the major tively hurricane-free period of 13 years from 1951 through hurricanemonths in 1964 the long-wavetrough failed 1963. -

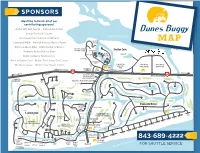

Dunes Buggy Map.Indd 1 Plaza at Shelter Cove • the Dunesbug- Leamington POA • LEAMINGT LIGHTHOUSE

TheSPONSORS Dunes Bug- We’d like to thank all of our contributing sponsors! Arthur Hills Golf Course • Disney’s HHI Resort George Fazio Golf Course BROAD CREE K Greenwood Communities and Resorts CAPTAIN’S MAP Leamington POA • Marriott Harbour/Sunset Pointe QUARTERS Palmetto Dunes POA • Palmetto Dunes Resort ELA’S BLUE WATER THE SHIP’S STORE ANCHORAGE Shelter Cove SHELTER COVE SHELTER COVE Palmetto Dunes General Store COMMUNITY PARK VETERANS MEMORIAL YACHT CLUB DISNEY NEWPORT Shelter Cove Lane Palmetto Dunes Tennis Center RESORT TRADEWINDS Plaza at Shelter Cove • Robert Trent Jones Golf Course HARBOURSIDE S C h I, II, III o e ve lt SHELTER COVE L er SHELTER COVE THE PLAZA AT The Dunes House • Shelter Cove Towne Centre an WATERS e EXECUTIVE TOWNE CENTRE SHELTER COVE EDGE PARK CHAMBER OF ARTS William Hilton Parkway COMMERCE CENTER Pedestrian Underpass 278 d te To Mainland To South En Security Ga WELCOME CENTER, Pedestrian Underpass 278 Interlochen Dr. CHECKIN, RENTALS William Hilton Parkway s n er REAL ESTATE SALES LEAMINGTON st Ma Stratford Merio PDPOA PASS OFFICE, SECURITY, ADMIN LIGHTHOUSE t Lane u o Yard Fire Station b arm A ind p To Leamington Lane Up Side Fron g O Shore W t e n i d i Gate T w k S c Niblick a l S y S ack Hi t Port T L gh a Wa ST. ANDREWS o W rb w a o Fu wn ll S te a weep W r o COMMON r d Wind T D at ack Brassie Ct. e Queens Queens r Leamington Ct. -

Guide to the Coastal Marine Fishes of California

STATE OF CALIFORNIA THE RESOURCES AGENCY DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME FISH BULLETIN 157 GUIDE TO THE COASTAL MARINE FISHES OF CALIFORNIA by DANIEL J. MILLER and ROBERT N. LEA Marine Resources Region 1972 ABSTRACT This is a comprehensive identification guide encompassing all shallow marine fishes within California waters. Geographic range limits, maximum size, depth range, a brief color description, and some meristic counts including, if available: fin ray counts, lateral line pores, lateral line scales, gill rakers, and vertebrae are given. Body proportions and shapes are used in the keys and a state- ment concerning the rarity or commonness in California is given for each species. In all, 554 species are described. Three of these have not been re- corded or confirmed as occurring in California waters but are included since they are apt to appear. The remainder have been recorded as occurring in an area between the Mexican and Oregon borders and offshore to at least 50 miles. Five of California species as yet have not been named or described, and ichthyologists studying these new forms have given information on identification to enable inclusion here. A dichotomous key to 144 families includes an outline figure of a repre- sentative for all but two families. Keys are presented for all larger families, and diagnostic features are pointed out on most of the figures. Illustrations are presented for all but eight species. Of the 554 species, 439 are found primarily in depths less than 400 ft., 48 are meso- or bathypelagic species, and 67 are deepwater bottom dwelling forms rarely taken in less than 400 ft.