Brutal Belonging in Melbourne's Grindcore Scene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Grindcore.Pdf

Obsah: 1. Úvod..........................................................................................................................2 1.1 Ideová východiska práce.............................................................................2 1.2 Stav bádání, primární a sekundární literatura.............................................3 1.3 Definice grindcore, důležité pojmy.............................................................3 1.4 Členění práce a metodologie.......................................................................6 1.5 Cíl práce......................................................................................................8 2. Historický úvod – žánrová typologie........................................................................9 2.1 Počátky žánru a dva hlavní proudy grindcoru............................................9 2.2 Další vývoj grindcoru................................................................................13 3. Grindcore – hledání extrémního hudebního projevu ….........................................17 3.1 Transformace zpěvu..................................................................................17 3.2 Vývoj rytmu, rytmické sekce....................................................................19 3.3 Vývoj hry na kytaru a baskytaru …..........................................................20 3.4 Vývoj formy a mikrostruktury..................................................................20 3.5 Goregrindové intro....................................................................................22 -

Info Sheet D

Czar Of Crickets Productions czarofcrickets.com / facebook.com/czarofcrickets / youtube.com/czarofcricketsproductions MINSK/ZATOKREV - BIGOD Minsk (USA) und Zatokrev (CH/EU); zwei verschiedenen Kontinenten entstammende Bands erschaen sich zwei gleichende, parallele Universen, welche nun bei ihrem gemeinsamen Projekt BIGOD verschmelzen. Es ist die Symbiose zweier Biograen mit Parallelen, Überlagerungen und Verechtungen. Minsk und Zatokrev gründeten sich im Jahr 2002 und veröentlichten bisher jeweils vier Alben. Im Laufe der Zeit kreuzten sich auf zahlreichen europäischen Tourneen immer wieder ihre Wege woraus sich schliesslich eine Freundschaft entwickelte. Sowohl Minsk als auch Zatokrev gingen seit Beginn an kompromisslos ihre eigenen Wege. Stetig auf der Suche nach einem tieferen Sinn im Hier und Jetzt, reektieren die Musiker immerwährend ihr Innerstes in Form einer psychedelischen Melancholie, gepaart mit einer gigantischen Schwere und schöpferischen Zerstörungswut. Artists: Minsk / Zatokrev Ihre gemeinsame Leidenschaft und Aura führte zur Idee für das Split-Album Split album title: BIGOD BIGOD. Dieses Werk erschat einen neuen Geist; einen Gott der zwei dunkle Homeland Minsk: USA Seelen vereint und zwei Pfade in einen verwandelt. Beide Bands komponierten Homeland Zatokrev: Switzerland Catalog Nr: SOUL0113 (CD) SOULCXIII (LP) jeweils zwei epische Songs, von denen jeweils einer gesangliche Unterstützung Format: digisleeve CD / Transparent 2LP w/ UV print der anderen Band erhielt. Barcode: 3481575154805 (CD) 3481575154812 (LP) Labels: Consouling Sounds / Czar Of Crickets Productions Um das Gesamtkunstwerk zu vollenden, kreierte der Pariser Künstler Max Loriot Release: October 5th 2018 Genre: Post-Metal, Psychedelic Rock, Post-Hardcore, Doom, Sludge eine aussergewöhnliche visuelle Umsetzung von BIGOD, die sich am Sinnbild For fans of: Neurosis, Cult Of Luna, Isis, Wolves In The Throne Room, von Elias Himmelfahrt orientiert. -

Melvins / Decrepit Birth Prosthetic Records / All

METAL ZINE VOL. 6 SCIONAV.COM MELVINS / DECREPIT BIRTH PROSTHETIC RECORDS / ALL SHALL PERISH HOLY GRAIL STAFF SCION A/V SCHEDULE Scion Project Manager: Jeri Yoshizu, Sciontist Editor: Eric Ducker MARCH Creative Direction: Scion March 13: Scion A/V Presents: The Melvins — The Bulls & The Bees Art Direction: BON March 20: Scion A/V Presents: Meshuggah — I Am Colossus Contributing Editor: J. Bennett March 31: Scion Label Showcase: Profound Lore, featuring Yob, the Atlas Moth, Loss, Graphic Designer: Gabriella Spartos Wolvhammer and Pallbearer, at the Glasshouse, Pomona, California CONTRIBUTORS Writer: Etan Rosenbloom Photographer: Mackie Osborne CONTACT For additional information on Scion, email, write or call. Scion Customer Experience 19001 S. Western Avenue Mail Stop WC12 APRIL Torrance, CA 90501 $WODV0RWK³<RXU&DOP:DWHUV´ Phone: 866.70.SCION / Fax: 310.381.5932 &RUURVLRQRI&RQIRUPLW\³3V\FKLF9DPSLUH´ Email: Email us through the Contact page located on scion.com 6DLQW9LWXV³/HW7KHP)DOO´ Hours: M-F, 6am-5pm PST / Online Chat: M-F, 6am-6pm PST 7RPEV³3DVVDJHZD\V´ Scion Metal Zine is published by BON. $SULO6FLRQ$93UHVHQWV0XVLF9LGHRV For more information about BON, email [email protected] April 3: Scion A/V Presents: Municipal Waste April 10: Scion A/V Presents: All Shall Perish — Company references, advertisements and/or websites The Past Will Haunt Us Both (in Spanish) OLVWHGLQWKLVSXEOLFDWLRQDUHQRWDI¿OLDWHGZLWK6FLRQ $SULO6FLRQ$93UHVHQWV3URVWKHWLF5HFRUGV/DEHO6KRZFDVH OLYHUHFRUGLQJ unless otherwise noted through disclosure. April 24: Municipal Waste, “Repossession” video Scion does not warrant these companies and is not liable for their performances or the content on their MAY advertisements and/or websites. May 15: Scion A/V Presents: Relapse Records Label Showcase (live recording) May 19: Scion Label Showcase: A389 Records Showcase, featuring Integrity, Ringworm, © 2012 Scion, a marque of Toyota Motor Sales U.S.A., Inc. -

GOREGRIND: Música Extrema E Política Underground1 Evelyn

GOREGRIND: música extrema e política underground1 Evelyn Christine da Silva Matos2 Resumo Este estudo relata pontos centrais que definem o gênero musical goregrind. A análise visa delinear o estilo, atentando a nuances e pertinências deste na vida social urbana. Utiliza-se dos conceitos “subcultura” e “cultura juvenil” nas reflexões, além de atender à legitimação baseada em compreensões simbólicas e sensoriais para formação de grupos; e situa o paradigma da hegemonia através da tradição e da normalização dos formatos sociais a fim de aproximar estilos que o subvertem. O artigo contribui com a apresentação do underground por meio de um dos estilos que o corresponde e encaminha à concepção parceira entre estilos subversivos da modernidade e pós-modernidade. Palavras-chave: música extrema; underground; cena. Abstract This study reports central points that define the musical genre goregrind. The analysis aims to delineate the style, considering the nuances and pertinences of this in urban social life. The concepts "subculture" and "youth culture" are used in the reflections, in addition to attending the legitimation based on symbolic and sensorial understandings for group formation; and situates the paradigm of hegemony through tradition and the normalization of social formats in order to approximate styles that subvert it. The article contributes to the presentation of the underground through one of the styles that corresponds to it and leads to the conception of the subversive styles of modernity and postmodernity. Key-words: extreme music; underground; scene. 1 Artigo submetido à 31ª Reunião Brasileira de Antropologia, realizada entre os dias 09 e 12 de dezembro de 2018, Brasília/DF. -

Metaldata: Heavy Metal Scholarship in the Music Department and The

Dr. Sonia Archer-Capuzzo Dr. Guy Capuzzo . Growing respect in scholarly and music communities . Interdisciplinary . Music theory . Sociology . Music History . Ethnomusicology . Cultural studies . Religious studies . Psychology . “A term used since the early 1970s to designate a subgenre of hard rock music…. During the 1960s, British hard rock bands and the American guitarist Jimi Hendrix developed a more distorted guitar sound and heavier drums and bass that led to a separation of heavy metal from other blues-based rock. Albums by Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath and Deep Purple in 1970 codified the new genre, which was marked by distorted guitar ‘power chords’, heavy riffs, wailing vocals and virtuosic solos by guitarists and drummers. During the 1970s performers such as AC/DC, Judas Priest, Kiss and Alice Cooper toured incessantly with elaborate stage shows, building a fan base for an internationally-successful style.” (Grove Music Online, “Heavy metal”) . “Heavy metal fans became known as ‘headbangers’ on account of the vigorous nodding motions that sometimes mark their appreciation of the music.” (Grove Music Online, “Heavy metal”) . Multiple sub-genres . What’s the difference between speed metal and death metal, and does anyone really care? (The answer is YES!) . Collection development . Are there standard things every library should have?? . Cataloging . The standard difficulties with cataloging popular music . Reference . Do people even know you have this stuff? . And what did this person just ask me? . Library of Congress added first heavy metal recording for preservation March 2016: Master of Puppets . Library of Congress: search for “heavy metal music” April 2017 . 176 print resources - 25 published 1980s, 25 published 1990s, 125+ published 2000s . -

Now Exclusively Distributed by ACXDC Street Date: He Had It Coming, 7˝ AVAILABLE NOW!

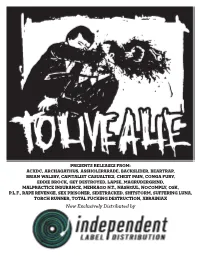

PRESENTS RELEASES FROM: ACXDC, ARCHAGATHUS, ASSHOLEPARADE, BACKSLIDER, BEARTRAP, BRIAN WALSBY, CAPITALIST CASUALTIES, CHEST PAIN, CONGA FURY, EDDIE BROCK, GET DESTROYED, LAPSE, MAGRUDERGRIND, MALPRACTICE INSURANCE, MEHKAGO N.T., NASHGUL, NOCOMPLY, OSK, P.L.F., RAPE REVENGE, SEX PRISONER, SIDETRACKED, SHITSTORM, SUFFERING LUNA, TORCH RUNNER, TOTAL FUCKING DESTRUCTION, XBRAINIAX Now Exclusively Distributed by ACXDC Street Date: He Had It Coming, 7˝ AVAILABLE NOW! INFORMATION: Artist Hometown: Los Angeles, CA Key Markets: LA & CA, Texas, Arizona, DC, Baltimore MD, New York, Canada, Germany For Fans of: MAGRUDERGRIND, NASUM, NAPALM DEATH, DESPISE YOU ANTI-CHRIST DEMON CORE’s He Had it Coming repress features the original six song EP released in 2005 plus two tracks from the same session off the A Sign Of Impending Doom Compilation. The band formed in 2003, recorded these songs in 2005 and then vanished for awhile on a many- year hiatus, only to resurface and record and release a brilliant new EP and begin touring again in 2011/2012. The original EP is long sought after ARTIST: ACXDC by grindcore and powerviolence fiends around the country and this is your TITLE: He Had It Coming chance to grab the limited repress. LABEL: TO LIVE A LIE CAT#: TLAL64AB Marketing Points: FORMAT: 7˝ GENRE: Grindcore • Hugely Popular Band BOX LOT: NA • Repress of Long Sold Out EP SRLP: $5.48 • Huge Seller UPC: 616983334836 • Two Extra Songs In Additional To Originals EXPORT: NO RESTRICTIONS • Two Bonus Songs Never Before Pressed To Vinyl, In Additional To Originals Tracklist: 1. Dumb N Dumbshit 2. Death Spare Not The Tiger 3. Anti-Christ Demon Core 4. -

From Crass to Thrash, to Squeakers: the Suspicious Turn to Metal in UK Punk and Hardcore Post ‘85

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by De Montfort University Open Research Archive From Crass to Thrash, to Squeakers: The Suspicious Turn to Metal in UK Punk and Hardcore Post ‘85. Otto Sompank I always loved the simplicity and visceral feel of all forms of punk. From the Pistols take on the New York Dolls rock, or the UK Subs aggressive punk take on rhythm and blues. The stark reality Crass and the anarchist-punk scene was informed with aspects of obscure seventies rock too, for example Pete Wright’s prog bass lines in places. Granted. Perhaps the most famous and intense link to rock and punk was Motorhead. While their early output and LP’s definitely had a clear nod to punk (Lemmy playing for the Damned), they appealed to most punks back then with their sheer aggression and intensity. It’s clear Motorhead and Black Sabbath influenced a lot of street-punk and the ferocious tones of Discharge and their Scandinavian counterparts such as Riistetyt, Kaaos and Anti Cimex. The early links were there but the influence of late 1970s early 80s NWOBM (New Wave of British Heavy Metal) and street punk, Discharge etc. in turn influenced Metallica, Anthrax and Exodus in the early eighties. Most of them can occasionally be seen sporting Discharge, Broken Bones and GBH shirts on their early record-sleeve pictures. Not only that, Newcastle band Venom were equally influential in the mix of new genre forms germinating in the early 1980s. One of the early examples of the incorporation of rock and metal into the UK punk scene came from Discharge. -

![[VXYJ]⋙ PERPETUAL CONVERSION: 30 Years and Counting in the Life of Metal Veteran Dan Lilker by Dave Hofer #G6KYEJQ8RBD #Free R](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7248/vxyj-perpetual-conversion-30-years-and-counting-in-the-life-of-metal-veteran-dan-lilker-by-dave-hofer-g6kyejq8rbd-free-r-1027248.webp)

[VXYJ]⋙ PERPETUAL CONVERSION: 30 Years and Counting in the Life of Metal Veteran Dan Lilker by Dave Hofer #G6KYEJQ8RBD #Free R

PERPETUAL CONVERSION: 30 Years and Counting in the Life of Metal Veteran Dan Lilker Dave Hofer Click here if your download doesn"t start automatically PERPETUAL CONVERSION: 30 Years and Counting in the Life of Metal Veteran Dan Lilker Dave Hofer PERPETUAL CONVERSION: 30 Years and Counting in the Life of Metal Veteran Dan Lilker Dave Hofer Perpetual Conversion traces the career of bassist Dan Lilker from 1981, the year he co-founded Anthrax, through 2011, and details numerous influential bands he founded or joined, including the groundbreaking Stormtroopers of Death (S.O.D.), thrash legends Nuclear Assault, grindcore trailblazers Brutal Truth, and one of the earliest US black metal bands, Hemlock. Although known among die-hard, underground metal fans, Lilker's influence has been significant across many genres. From his signature heavily distorted bass tone to his unquenchable thirst to create forward- thinking, aggressive music, Lilker's musical drive has seen him at the forefront of New York hardcore, crossover, thrash, grindcore, and black metal. Perpetual Conversion is culled from extensive interviews conducted by author Dave Hofer with Lilker, his family, his peers, and his bandmates past and present, including personal accounts from Craig Setari of Sick of It All, Barney Greenway of Napalm Death, Dave Witte of Municipal Waste, Scott Ian of Anthrax, Gene Hoglan of Death/Dark Angel, Kevin Sharp of Brutal Truth, Digby Pearson of Earache Records, Fenriz of Darkthrone, Chris Reifert of Death/Autopsy, rapper Necro, Dave Mustaine of Megadeth, Jacob Bannon of Converge, and many others. In addition, the book is supplemented with excerpts from historic interviews, key reviews, and dozens of previously unseen images. -

Masterarbeit / Master's Thesis

d o n e i t . MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS R Tit e l der M a s t erarbei t / Titl e of the Ma s t er‘ s Thes i s e „What Never Was": a Lis t eni ng to th e Genesis of B lack Met al d M o v erf a ss t v on / s ubm itted by r Florian Walch, B A e : anges t rebt e r a k adem is c her Grad / i n par ti al f ul fi l men t o f t he requ i re men t s for the deg ree of I Ma s ter o f Art s ( MA ) n t e Wien , 2016 / V i enna 2016 r v i Studien k enn z ahl l t. Studienbla t t / A 066 836 e deg r ee p rogramm e c ode as i t appea r s o n t he st ude nt r eco rd s hee t: w Studien r i c h tu ng l t. Studienbla tt / Mas t er s t udi um Mu s i k w is s ens c ha ft U G 2002 : deg r ee p r o g r amme as i t appea r s o n t he s tud e nt r eco r d s h eet : B et r eut v on / S uper v i s or: U ni v .-Pr o f. Dr . Mi c hele C a l ella F e n t i z |l 2 3 4 Table of Contents 1. -

Exploring the Chinese Metal Scene in Contemporary Chinese Society (1996-2015)

"THE SCREAMING SUCCESSOR": EXPLORING THE CHINESE METAL SCENE IN CONTEMPORARY CHINESE SOCIETY (1996-2015) Yu Zheng A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2016 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Esther Clinton Kristen Rudisill © 2016 Yu Zheng All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This research project explores the characteristics and the trajectory of metal development in China and examines how various factors have influenced the localization of this music scene. I examine three significant roles – musicians, audiences, and mediators, and focus on the interaction between the localized Chinese metal scene and metal globalization. This thesis project uses multiple methods, including textual analysis, observation, surveys, and in-depth interviews. In this thesis, I illustrate an image of the Chinese metal scene, present the characteristics and the development of metal musicians, fans, and mediators in China, discuss their contributions to scene’s construction, and analyze various internal and external factors that influence the localization of metal in China. After that, I argue that the development and the localization of the metal scene in China goes through three stages, the emerging stage (1988-1996), the underground stage (1997-2005), the indie stage (2006-present), with Chinese characteristics. And, this localized trajectory is influenced by the accessibility of metal resources, the rapid economic growth, urbanization, and the progress of modernization in China, and the overall development of cultural industry and international cultural communication. iv For Yisheng and our unborn baby! v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to show my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Dr. -

Toxic Holocaust USA / Metal - Thrash - Grind - Death - Metalcore

Toxic Holocaust USA / Metal - Thrash - Grind - Death - Metalcore hfmncrew.com Press Kit / Toxic Holocaust USA / Metal - Thrash - Grind - Death - Metalcore Influenciado por el punk rock y heavy metal de bandas de la década de 1980 como Slayer, Exodus, Black Flag, Discharge, Motörhead, Kreator o Venom la banda nació en 1999 por Joel Grind por su deseo y afán de fusionar 2 de sus géneros preferidos; punk y metal. El resultado es un thrash metal incesante con riffs de guitarra frenéticos unido a una voz grave y desgarrada. Todos estos elementos añadidos a una actitud DIY forman a este trío de Portland (USA). Desde su primer trabajo, "Evil Never Dies", TOXIC HOLOCAUST han luchado por hacerse un hueco en el mundillo y lo han logrado a base de mucho sudor y trabajo. Su tercer CD, "An Overdose of Death...", fue el gran salto para la banda, ya que fue el primer disco que grabaron en un estudio profesional (sus primeros discos fueron producciones caseras) y contaron con el productor Jack Endino (High On Fire, Dwarves, Zeke) para la grabación. El salto de calidad con respecto a sus anteriores trabajos es considerable, con himnos que podrían ser la banda sonora en un mundo post- apocalíptico que se ha vuelto loco. Relapse Records fue el sello discográfico que lanzó este trabajo y han continuado apoyando a TOXIC HOLOCAUST desde entonces. Ahora el grupo nos presenta su quinto disco, "Chemistry of Consciousnes", un torbellino de thrash metal que viene pisando fuerte. hfmncrew.com Press Kit / Toxic Holocaust Videos hfmncrew.com Press Kit / Toxic Holocaust Enlaces hfmncrew.com http://www.hfmncrew.com/roster/toxic-holocaust Página oficial http://www.toxicholocaust.com Facebook https://www.facebook.com/ToxicHolocaust hfmncrew.com.