House of Representatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corangamite Heritage Study Stage 2 Volume 3 Reviewed

CORANGAMITE HERITAGE STUDY STAGE 2 VOLUME 3 REVIEWED AND REVISED THEMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY Prepared for Corangamite Shire Council Samantha Westbrooke Ray Tonkin 13 Richards Street 179 Spensley St Coburg 3058 Clifton Hill 3068 ph 03 9354 3451 ph 03 9029 3687 mob 0417 537 413 mob 0408 313 721 [email protected] [email protected] INTRODUCTION This report comprises Volume 3 of the Corangamite Heritage Study (Stage 2) 2013 (the Study). The purpose of the Study is to complete the identification, assessment and documentation of places of post-contact cultural significance within Corangamite Shire, excluding the town of Camperdown (the study area) and to make recommendations for their future conservation. This volume contains the Reviewed and Revised Thematic Environmental History. It should be read in conjunction with Volumes 1 & 2 of the Study, which contain the following: • Volume 1. Overview, Methodology & Recommendations • Volume 2. Citations for Precincts, Individual Places and Cultural Landscapes This document was reviewed and revised by Ray Tonkin and Samantha Westbrooke in July 2013 as part of the completion of the Corangamite Heritage Study, Stage 2. This was a task required by the brief for the Stage 2 study and was designed to ensure that the findings of the Stage 2 study were incorporated into the final version of the Thematic Environmental History. The revision largely amounts to the addition of material to supplement certain themes and the addition of further examples of places that illustrate those themes. There has also been a significant re-formatting of the document. Most of the original version was presented in a landscape format. -

YEAR in BRIEF CONTENTS 2010 - 2011 1

YEAR in BRIEF CONTENTS 2010 - 2011 1 PERFORMANCE INDICATORS Year in Brief 1 Performance Indicators 1 % 2010/11 2009/10 Variance Change Financial Results appendix 1 Performance at a glance appendix 1 Hospital inpatients treated (separations) Highlights 2 Warrnambool 19,191 17,363 1,828 10.53 Camperdown 1,824 1,793 31 1.73 Chairman and CEO’s Report 3 Inpatients average length of stay Warrnambool 2.72 2.96 -0.24 -8.11 Statement of Strategic Direction 7 Camperdown 2.81 3.10 -0.29 -9.35 Statement of Priorities 8 Inpatients bed days Warrnambool 52,391 51,843 548 1.06 Statistical Information 10 Camperdown 5,161 5,539 -378 -6.82 Nursing Home bed days 9,029 10,162 -1,133 -11.15 Profile 14 Hostel bed days 2,459 2,671 -212 -7.94 Our Locations 14 Our Services 14 Non admitted patient attendances Services and Programs 16 Warrnambool 84,782 82,173 2,609 3.18 Our Patients 18 Camperdown 20,339 21,825 -1,486 -6.81 Quality Management 20 Emergency attendances Warrnambool 25,593 24,549 1,044 4.25 Education and Training 22 Camperdown 2,659 2,860 -201 -7.03 Fundraising Research 25 Capital 1,179,757 566,058 613,699 108.42 Volunteers 27 Full Time Equivalent staff 874.10 838.97 35.13 4.19 Occupational Health and Safety 28 Corporate and Clinical Governance 30 Board of Directors 30 Organisational Structure 32 Executive Team 33 Principal Committees 34 Senior Staff 35 Life Governors 38 Donors 40 Disclosure Index appendix 2 Statutory Requirements appendix 3 Financial Statements appendix 4 In the past 12 months, our health service, our Quality of Care Report and a volunteer have been named regional Victoria’s best. -

Shire of Corangamite 2010

Early Childhood Community Profile Shire of Corangamite 2010 Early Childhood Community Profile Shire of Corangamite 2010 This Early Childhood community profile was prepared by the Office for Children and Portfolio Coordination, in the Victorian Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. The series of Early Childhood community profiles draw on data on outcomes for children compiled through the Victorian Child and Adolescent Monitoring System (VCAMS). The profiles are intended to provide local level information on the health, wellbeing, learning, safety and development of young children. They are published to: • Equip communties with the information required to identify the needs of children and families within their local government area. • Aid Best Start partnerships with local service development, innovation and program planning to improve outcomes for young children. • Support local government and regional planning of early childhood services; and • Assist community service agencies working with vulnerable families and young people. The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, the Department of Human Services, the Department of Health and the Australian Bureau of Statistics provided data for this document. Early Childhood Community Profiles i Published by the Victorian Government Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. September 2010 © Copyright State of Victoria, Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, 2010 This publication is copyright. No -

Council Spring Weekly Book 4 2004

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-FIFTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION 3 November 2004 (extract from Book 4) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor JOHN LANDY, AC, MBE The Lieutenant-Governor Lady SOUTHEY, AM The Ministry Premier and Minister for Multicultural Affairs ....................... The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Environment, Minister for Water and Minister for Victorian Communities.............................. The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Finance and Minister for Consumer Affairs............... The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Education Services and Minister for Employment and Youth Affairs....................................................... The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Transport and Minister for Major Projects................ The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Local Government and Minister for Housing.............. The Hon. C. C. Broad, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Innovation and Minister for State and Regional Development......................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Agriculture........................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Planning, Minister for the Arts and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. M. E. Delahunty, MP Minister for Community Services.................................. The Hon. S. M. Garbutt, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services -

Corangamite Shire Landslide Inventory

Dahlhaus Environmental Geology Pty Ltd Timboon Corangamite Shire Landslide Inventory 664000 665000 666000 667000 668000 669000 670000 671000 672000 673000 674000 Neilsons Road 5750000 5750000 K E E R Timboon-Terang Road C P Ecklin South E E D Leichfield Road Mckinnons Road 5749000 5749000 Cobden-Warrnambool Road EK RE C LL Troups Road E N BRUC K Glenfyne 5748000 5748000 Curdies-Leichfield Road 5747000 5747000 Morehouses Bridge Road Bridge Morehouses New Brucknell Road 5746000 5746000 Missens Road Curdies-Leichfield Road Merretts Road 5745000 5745000 CORANGAMITE 5744000 5744000 Curdies River Road S 5743000 5743000 C O T T S C R E E Moreys Road K Loves Road d a o R e g 5742000 d 5742000 ri B s y e n g i Glenfyne-Brucknell Road D Haynes Road Browns Road 5741000 Brucknell 5741000 oad c R ola C n- o bo m Timboon-Nullawarre Road Ti 5740000 5740000 Curdies River Road Digneys Bridge Road ES RIVE R I et D tre R S t U t e C rr a S B Timboon na ke T r ac 5739000 k 5739000 Street Bailey MOYNE N Robilliards Road T im H Robilliards Road b o o n -P Timboon-Curdievale Road or 5738000 t C 5738000 am pb el l R F o E a N d TON C R E E K Boundary Road 664000 665000 666000 667000 668000 669000 670000 671000 672000 673000 674000 Projection: Universal Transverse Mercator projection Zone 54 Datum: Geocentric Datum of Australia GDA94 1:25,000 (at A1 sheet size) Legend Pura Pura 0 250 500 750 1,000 Mapped Landslides - Data Sources* Base Map Features Highway Darlington Metres Buenen 1995- - 1:25,000 Feltham 2006 - 1:2,000 Derrinallum Berrybank Wilgul Feltham 2006 Arterial Roads User Comments: Users noting any errors or omissions are Cooney 1980- - 1:100,000 Unconfirmed - 1:2,000 Mount invited to notify (in writing): Koang Cressy Feltham 2004 Local Roads Corangamite Catchment Management Authority Cooney 1980- - 1:100,000 Unconfirmed - 1:2,000 Email: [email protected] Lake Camperdown Tracks Gnotuk Feltham 2004 - 1:2,000 Map created on: Apr 05, 2007 Landcare 2005 - Field Obs. -

Extract from Book 2)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Tuesday, 20 February 2018 (Extract from book 2) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable KEN LAY, AO, APM The ministry (from 16 October 2017) Premier ........................................................ The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Education and Minister for Emergency Services...................................................... The Hon. J. A. Merlino, MP Treasurer and Minister for Resources .............................. The Hon. T. H. Pallas, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Major Projects .......... The Hon. J. Allan, MP Minister for Industry and Employment ............................. The Hon. B. A. Carroll, MP Minister for Trade and Investment, Minister for Innovation and the Digital Economy, and Minister for Small Business ................ The Hon. P. Dalidakis, MLC Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change, and Minister for Suburban Development ....................................... The Hon. L. D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Roads and Road Safety, and Minister for Ports ............ The Hon. L. A. Donnellan, MP Minister for Tourism and Major Events, Minister for Sport and Minister for Veterans ................................................. The Hon. J. H. Eren, MP Minister for Housing, Disability and Ageing, Minister for Mental Health, Minister for Equality and Minister for Creative Industries .......... The Hon. M. P. Foley, MP Minister for Health and Minister for Ambulance Services ............. The Hon. J. Hennessy, MP Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, Minister for Industrial Relations, Minister for Women and Minister for the Prevention of Family Violence ............................................. The Hon. N. M. Hutchins, MP Special Minister of State ......................................... The Hon. G. -

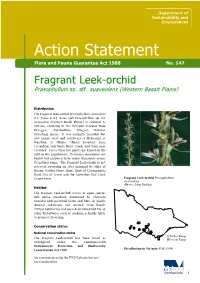

Fragrant Leek-Orchid Prasophyllum Sp

Action Statement Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 No. 147 Fragrant Leek-orchid Prasophyllum sp. aff. suaveolens (Western Basalt Plains) Distribution The Fragrant Leek-orchid [Prasophyllum suaveolens D.L. Jones & R.J. Bates and Prasophyllum sp. aff. suaveolens (Western Basalt Plains)] is endemic to Victoria, occurring in the Victorian Volcanic Plain Bioregion (Derrinallum, Wingeel, Ballarat, Streatham areas). It was formerly recorded but now extinct west and southwest of Melbourne at Werribee, St Albans, Albion, Laverton, Lara, Tottenham and Merri Merri Creek, and from near Creswick. Fewer than 300 plants are known in the wild, in five populations. Its former abundance not known but assumed to be many thousands across its natural range. The Fragrant Leek-orchid is not reserved, occurring on sites managed by Shire of Moyne, Golden Plains Shire, Shire of Corangamite, Rural City of Ararat and the Australian Rail Track Corporation. Fragrant Leek-orchid Prasophyllum suaveolens (Photo: John Eichler) Habitat The Fragrant Leek-orchid occurs in open species rich native grassland dominated by Themeda triandra with perennial herbs and lilies on poorly drained red-brown soil derived from basalt. Critical habitat has not been determined but fire or other disturbance such as slashing is highly likely to promote flowering. Conservation status National conservation status Former Range The Fragrant Leek-orchid has been listed as Ξ ] Present Range endangered under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Distribution in Victoria (DSE 2004) Conservation Act 1999. An assessment using the IUCN Criteria has not been undertaken. 1 Victorian conservation status • The Western (Basalt) Plains Grassland habitat Fragrant Leek-orchid has been listed as threatened where P. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION TUESDAY, 2 FEBRUARY 2021 hansard.parliament.vic.gov.au By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable KEN LAY, AO, APM The ministry Premier........................................................ The Hon. DM Andrews, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Education and Minister for Mental Health .. The Hon. JA Merlino, MP Attorney-General and Minister for Resources ....................... The Hon. J Symes, MLC Minister for Transport Infrastructure and Minister for the Suburban Rail Loop ....................................................... The Hon. JM Allan, MP Minister for Training and Skills and Minister for Higher Education .... The Hon. GA Tierney, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Economic Development and Minister for Industrial Relations ........................................... The Hon. TH Pallas, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Roads and Road Safety . The Hon. BA Carroll, MP Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change and Minister for Solar Homes ................................................ The Hon. L D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Child Protection and Minister for Disability, Ageing and Carers ...................................................... The Hon. LA Donnellan, MP Minister for Health, Minister for Ambulance Services and Minister for Equality .................................................... The Hon. MP -

Panel Report

CORANGAMITE PLANNING SCHEME AMENDMENT C3 PANEL REPORT JULY 2006 CORANGAMITE PLANNING SCHEME AMENDMENT C3 PANEL REPORT ELIZABETH JACKA, CHAIR HELEN MARTIN, MEMBER JULY 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY.................................................................................................................. 1 2. WHAT IS PROPOSED? ............................................................................................. 3 2.1 CORANGAMITE PLANNING SCHEME – HERITAGE OVERLAY ..................... 3 2.2 THE AMENDMENT.................................................................................................. 3 3. STRATEGIC CONTEXT........................................................................................... 5 3.1 STRATEGIC PLANNING FRAMEWORK .............................................................. 5 3.1.1 LEGISLATED PRINCIPLES ............................................................................... 5 3.1.2 SPPF.................................................................................................................... 5 3.1.3 LPPF.................................................................................................................... 6 3.1.4 HERITAGE GUIDELINES & PLANNING PRACTICE NOTE........................... 8 3.1.5 CAMPERDOWN HERITAGE STUDY .............................................................. 11 3.2 STATUTORY PLANNING FRAMEWORK........................................................... 12 3.2.1 HERITAGE OVERLAY..................................................................................... -

Rural Roadside Management Plan Corangamite Shire February 2012 Table of Contents

Rural Roadside Management Plan Corangamite Shire February 2012 Table of Contents Executive Summary i PART A – INTRODUCING THE RURAL ROADSIDE MANAGEMENT PLAN 1 1 Introduction 2 1.1 Structure of the Plan 2 1.2 Plan purpose and review 3 PART B – RURAL ROADSIDE MANAGEMENT IN THE CORANGAMITE SHIRE 4 2 Rural roadside management in the Corangamite Shire 5 2.1 Vision 5 2.2 Scope 5 2.3 Achieving balanced actions 5 2.4 Goals of rural roadside management 7 PART C – GOALS OF RURAL ROADSIDE MANAGEMENT 9 3 Goal 1: Maintain a safe local road network 10 3.1 Introducing the safe roads goal 10 3.2 Legislative context to vegetation removal 10 3.3 Drainage and pavement maintenance (routine) 11 3.4 Vegetation control to restore sightlines 11 3.5 Strategies in maintaining a safe local road network 12 4 Goal 2: Protect natural and heritage assets 13 4.1 Introducing the assets protection goal 13 4.2 Biodiversity protection and enhancement 14 4.3 Invasive plants and animals 15 4.4 Aboriginal and non Aboriginal heritage 17 4.5 Strategies in protecting natural and heritage assets 18 5 Goal 3: Manage third party access 19 5.1 Introducing the third party access goal 19 5.2 Fire prevention 20 5.3 Utility and service provision 20 5.4 Adjoining landholders 21 5.5 Recreational users 21 5.6 Strategies in managing third party access risks 21 6 Goal 4: Provide leadership and promote the value and function of rural roadsides 23 6.1 Introducing the leadership goal 23 6.2 Community awareness 23 6.3 Stakeholder cooperation 23 6.4 Strategies in promoting the value and function -

MHCSS Barwon South Western Region Fact Sheet 1

Mental Health Community Support Services Fact Sheet 1: New service delivery responsibilities May 2014 Barwon South Western Region As a result of extensive consultation and review with clients, families, carers and service providers, the Victorian Government is introducing changes to the delivery of Mental Health Community Support Services (MHCSS) across the state. This fact sheet provides information on the service providers selected through an open competitive process to deliver a total of $2.19 million in MHCSS in the Department of Health Barwon South Western Region. Mental Health Community Support Services (previously called Psychiatric Disability Rehabilitation and Support Services) provide broad-ranging psychosocial support to people aged 16-64 years with a psychiatric disability. They are an essential part of the state-funded specialist mental health and broader health and human services systems. As part of these reforms, $74 million in MHCSS has been redesigned and recommissioned, largely in the form of new Individualised Client Support Packages and Youth Residential Rehabilitation Services . Importantly, funding will be maintained across the region as a result of this process. The reason for the reform is that we were told by clients that the service system is complicated and difficult to navigate and service quality is variable. Service providers also told us that the program and funding models are rigid and prevented them responding flexibly to the changing needs of clients. The status quo simply was not giving people with mental illness in our communities the best support. The majority of the MHCSS funding ($60 million per annum) will be spent on the delivery of Individualised Client Support Packages, which will be tailored to the individual’s needs and preferences . -

G.J. Bradding

The Moorabool News FREE EMAIL: [email protected] Your Local News WEB: www.themooraboolnews.com.au Tuesday 27 October, 2015 Serving Ballan and district since 1872 Phone 5368 1966 Fax 5368 2764 Vol 9 No 42 CHEERS: Shirley and Alan McLean (St Anne’s Winery) toast their success. Photo: Helen Tatchell Excellent business By Jessica Howard St Anne’s Winery is a family owned and operated winery Vice-President, Peter Whitefield said the event was an that was established by the McLean family in 1972. exciting culmination of nearly two years of planning and St Anne’s Winery has been crowned the 2015 Business of the Owner, Alan McLean said he was blown away by the achievement. Year. recognition. “Our aim was to showcase the region’s businesses and The Myrniong-based winery claimed the top honour at the “It is just so very, very special for everyone at St Anne’s. acknowledge their business vision, innovation, marketing inaugural Business Excellence Awards last Friday evening. Shirley and I and the kids have built this from scratch and and great customer service,” he said. Organised by the Ballan & District Chamber of Commerce, it is something we are just so passionate about – the wine, “We congratulate all the nominated businesses, especially the presentation attracted around 160 guests from across the the environment, the buildings and the tourist industry,” he region’s business community. those willing to be involved in the judging process. Be said. Nine businesses were declared winners in their respective proud that you were recognised and applauded by your categories, with St Anne’s Winery taking out the coveted “This has been the most special thing that has happened to com mu n it y ”.