Scaling Innovation for Strong Upazila Health Systems September 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

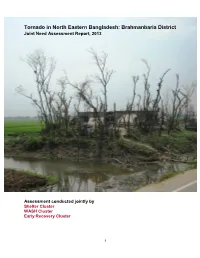

Brahmanbaria District Joint Need Assessment Report, 2013

Tornado in North Eastern Bangladesh: Brahmanbaria District Joint Need Assessment Report, 2013 Assessment conducted jointly by Shelter Cluster WASH Cluster Early Recovery Cluster 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary....................................................................................................... 6 Recommended Interventions......................................................................................... 8 Background.................................................................................................................... 10 Assessment Methodology.............................................................................................. 12 Key Findings.................................................................................................................. 14 Priorities identified by Upazila Officials.......................................................................... 18 Detailed Assessment Findings...................................................................................... 20 Shelter........................................................................................................................ 20 Water Sanitation & Hygiene....................................................................................... 20 Livelihoods.................................................................................................................. 21 Education.................................................................................................................... 24 -

Bandarban-S.Pdf

92°5'0"E 92°10'0"E 92°15'0"E 92°20'0"E 92°25'0"E UPAZILA MAP UPAZILA BANDARBAN SADAR DISTRICT BANDARBAN z# UPAZILA RAJASTHALI Rajbila z# DISTRICT RANGAMATI N " 0 z#T$ ' 0 N $T $ z# 2 " T ° 0 2 ' 2 0 2 ° 2 2 UPAZILA RANGUNIA Jhonka Islamp$Tur Bazar DISTRICT CHATTOGRAM z# z# z# z# z# z# z# z# z# z# z# Ñ z# Ñ N " 0 UPAZILA CHANDANAISH z#Chemi Dolupara Bazar ' $TT$ 5 1 N " z# ° 0 2 ' DISTRICT CHATTOGRAM z# Ghungru Bazar 2 5 1 $T ° 2 z# 2 z# z# Bagmz#ara Bazar z# S# L E G E N D Kuhz#a$Tlongz# Administrative Boundary z# z# } } } International Boundary Balaghata Bazar(M.A) Goaliakhola Bazar $T $T z# z# Division Boundary z# BANDARBAN z# T$ Ñ District Boundary z# z# z# z# Marma Baza$Tr(Mz#.A) Upazila Boundary z#[% T$ z# z# cz#$Tz#þ z#{# $T z# Union Boundary Bandarban Bazarz#(M.A) x% z# z# z#Kaz#lagata Bazar(M.A) Municipal Boundary z# z# z# z# N Administrative Headquarters z# " 0 ' z# 0 1 N " [% District ° 0 2 ' T$ BANDARBAN SADAR 2 0 z# 1 Upazila T$ ° Y# 2 S#Y# 2 $T Union Raicha Bazar z# UPAZILA ROWANGCHHARI Suaz#lock Physical Infrastructures $TMajer Para Bazar $Tz# |# National Highways S# Suwalok Bazar z# Regional Highways z# z# Zila Road VagT$gokul Bazar Upazila Road (Pucca) z#$T Upazila Road (Katcha) UPAZILA SATK ANIA z# Ñ DISTRICT CHATTOGRAM Union Road (Pucca) z# Union Road (Katcha) Village Road A (Pucca) z# z# N " 0 ' Village Road A (Katcha) 5 ° N " 2 0 2 ' 5 Village Road B (Pucca) ° 2 2 Village Road B (Katcha) z# Railway Network Embankment Chimbuk 16 Mile Baz$Tar Natural Features z# Wide River with Sandy Area z# Small River/ Khal Water Bodies -

Bangladesh – BGD34387 – Lalpur – Sonapur – Noakhali – Dhaka – Christians – Catholics – Awami League – BNP

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: BGD34387 Country: Bangladesh Date: 25 February 2009 Keywords: Bangladesh – BGD34387 – Lalpur – Sonapur – Noakhali – Dhaka – Christians – Catholics – Awami League – BNP This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please update on the situation for Catholics in Dhaka. 2. Are there any reports to suggest that Christians (or Catholics) tend to support or be associated with the BNP or AL generally, or whether this might depend on local conditions? 3. Are there any reports of a Catholic community in Lalpur (village) or Sonapur (local area) of Noakhali; in particular, their size and whether they are long-established? 4. If so, is there any material to indicate their mistreatment or serious incidents? 5. Please update on the treatment of BNP ‘field workers’ or supporters following the election of the AL Government. Any specific references to Dhaka or Noakhali would be useful. RESPONSE 1. Please update on the situation for Catholics in Dhaka. Question 2 of recent RRT Research Response BGD34378 of 17 February 2009 refers to source information on the situation of Catholics in Dhaka. -

CARITAS BANGLADESH Office Wise Location

CARITAS BANGLADESH Sustainable Agriculture and Production Linked to Improved Nutrition Status, Resilience and Gender Equity (SAPLING) Project Office Wise Location/ Address Exhibit -1 SL No. Name of Office Address 2 Outer Circular Road, 1 Central Office Shantibagh, Dhaka – 1217 1/E, Baizid Bostami Road 2 Chittagong Regional Office East Nasirabad, Panchalaish Bandarban Hill District Council’s rest House,Chimbuk Road 3 Bandarban District Office Bandarban Sadar. Bandarban: 4 Upazila Office P.O: Bandarban, Dist.: Bandarban Mhoharam Ali Bilding , Kalaghata Tripura Para, Bandarban sadar, 5 Sadar Union Office Bandarban. Balaghata Bazar,Rajvilla Chairman market Goli, Monchiggoy 6 Kuhalong Union Office : House,Bandarban sadar, Bandarban. Rangamati Road Udalbuniya Headman para ,Rajvilla High School, 7 Rajvilla Union Office Bandarban. Lama Road ,Majer Para Swalok Union Buddha Mondir pase, 8 Swalok Union office Bandarban . Swalok Headman Para, Lama Bandarban Road Swalok Union, 9 Tongkaboti Union Offce Bandarban . Lama Chotto Nunar Bil, 3no. Word, Lama Sadar area, Lama Upazila, 10 Upazila Office Bandarban . (Nearest ASP office) 11 Sadar Union Office Noya para (Nearest of Lama High School),Lama Pourashava. 12 Ruposhi Union Office Ibrahim Lidar Para, 6no. Rupashi Union, Lama, Bandarban . Charbagan Satghor Para 13 Fashiakhali Union Office Malumghat, Dulahazra Union Chokoria Upazila, Cox’s Bazer. 14 Soroi Union Office Kiaju Bazer Para, 4no. Soroi Union, Lama, Bandarban . 15 Gojalia Union Office Headmen Karjaloi, 305 no. Gojalia Moja, Gojalia, Lama, Bandarban . Chairman Para, 3no Word, Aziznagarbazar, Lama Upazila, Bandarban 16 Aziz Nagar Union Office . 6no. Word, Noya Para, Faiton Union, Lama, Bandarban . (Nearest 17 Faiton Union Office Abu Sawdagor house) Ruma Ruma Upazila Parishad, Jhorapalok Vhabon, Ruma Upazila, 18 Upazila Office Bandarban. -

Barisal -..:: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics

‡Rjv cwimsL¨vb 2011 ewikvj District Statistics 2011 Barisal June 2013 BANGLADESH BUREAU OF STATISTICS STATISTICS AND INFORMATICS DIVISION MINISTRY OF PLANNING GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH District Statistics 2011 District Statistics 2011 Published in June, 2013 Published by : Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Printed at : Reproduction, Documentation and Publication (RDP) Section, FA & MIS, BBS Cover Design: Chitta Ranjon Ghosh, RDP, BBS ISBN: For further information, please contract: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Statistics and Informatics Division (SID) Ministry of Planning Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Parishankhan Bhaban E-27/A, Agargaon, Dhaka-1207. www.bbs.gov.bd COMPLIMENTARY This book or any portion thereof cannot be copied, microfilmed or reproduced for any commercial purpose. Data therein can, however, be used and published with acknowledgement of the sources. ii District Statistics 2011 Foreword I am delighted to learn that Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) has successfully completed the ‘District Statistics 2011’ under Medium-Term Budget Framework (MTBF). The initiative of publishing ‘District Statistics 2011’ has been undertaken considering the importance of district and upazila level data in the process of determining policy, strategy and decision-making. The basic aim of the activity is to publish the various priority statistical information and data relating to all the districts of Bangladesh. The data are collected from various upazilas belonging to a particular district. The Government has been preparing and implementing various short, medium and long term plans and programs of development in all sectors of the country in order to realize the goals of Vision 2021. -

Division Name District Name Upazila Name 1 Dhaka 1 Dhaka 1 Dhamrai 2 Dohar 3 Keraniganj 4 Nawabganj 5 Savar

Division name District Name Upazila Name 1 Dhaka 1 Dhamrai 1 Dhaka 2 Dohar 3 Keraniganj 4 Nawabganj 5 Savar 2 Faridpur 1 Alfadanga 2 Bhanga 3 Boalmari 4 Char Bhadrasan 5 Faridpur Sadar 6 Madhukhali 7 Nagarkanda 8 Sadarpur 9 Saltha 3 Gazipur 1 Gazipur Sadar 2 Kaliakoir 3 Kaliganj 4 Kapasia 5 Sreepur 4 Gopalganj 1 Gopalganj Sadar 2 Kasiani 3 Kotalipara 4 Maksudpur 5 Tungipara 5 Jamalpur 1 Bakshiganj 2 Dewanganj 3 Islampur 4 Jamalpur Sadar 5 Madarganj 6 Melandah 7 Sharishabari 6 Kishoreganj 1 Austogram 2 Bajitpur 3 Bhairab 4 Hosainpur 5 Itna 6 Karimganj 7 Katiadi 8 Kishoreganj Sadar 9 Kuliarchar 10 Mithamain 11 Nikli 12 Pakundia 13 Tarail 7 Madaripur 1 Kalkini 2 Madaripur Sadar 3 Rajoir 4 Shibchar 8 Manikganj 1 Daulatpur 2 Ghior 3 Harirampur 4 Manikganj Sadar 5 Saturia 6 Shibalaya 7 Singair 9 Munshiganj 1 Gazaria 2 Lauhajang 3 Munshiganj Sadar 4 Serajdikhan 5 Sreenagar 6 Tangibari 10 Mymensingh 1 Bhaluka 2 Dhubaura 3 Fulbaria 4 Fulpur 5 Goffargaon 6 Gouripur 7 Haluaghat 8 Iswarganj 9 Mymensingh Sadar 10 Muktagacha 11 Nandail 12 Trishal 11 Narayanganj 1 Araihazar 2 Bandar 3 Narayanganj Sadar 4 Rupganj 5 Sonargaon 12 Norshingdi 1 Belabo 2 Monohardi 3 Norshingdi Sadar 4 Palash 5 Raipura 6 Shibpur 13 Netrokona 1 Atpara 2 Barhatta 3 Durgapur 4 Kalmakanda 5 Kendua 6 Khaliajuri 7 Madan 8 Mohanganj 9 Netrokona Sadar 10 Purbadhala 14 Rajbari 1 Baliakandi 2 Goalunda 3 Pangsha 4 Rajbari Sadar 5 Kalukhale 15 Shariatpur 1 Bhedarganj 2 Damudiya 3 Gosairhat 4 Zajira 5 Naria 6 Shariatpur Sadar 16 Sherpur 1 Jhenaigati 2 Nakla 3 Nalitabari 4 Sherpur Sadar -

Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project (CHTRDP II)

Semi-annual Environmental Monitoring Report Project No. 42248-013 June 2019 Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project (CHTRDP II) This Semi-annual Environmental Monitoring Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Project No. 42248-013 Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project J an – June 2019 June Environmental Monitoring Report 0 Environmental Monitoring Report Jan – June 2019 2763-BAN (SF): Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project CHTRDP II Project No. 42248-013 Environmental Monitoring Report Jan-June 2019 Prepared by: Md.Maksudul Amin Environmental Engineer (Individual Consultant) Safeguard and Quality Monitoring Cell (SQMC) Project Management Office Second Chittagong Hill Ttracts Rural Development Project, for the Peoples Republic of Bangladesh and The Asian Development Bank 1 Environmental Monitoring Report Jan – June 2019 This environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Mineralogical Study of Sediment Samples of Kachua, Chandpur District for Investigation of Arsenic Bearing Minerals

2 MINERALOGICAL STUDY OF SEDIMENT SAMPLES OF KACHUA, CHANDPUR DISTRICT FOR INVESTIGATION OF ARSENIC BEARING MINERALS NASIR AHMED, MOHAMMAD MIKAIL Isotope Hydrology Division, Institute of Nuclear Science & Technology, Atomic Energy Research Establishment, Ganakbari, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh AND D. K. SAHA Materials Science Division, Atomic Energy Centre, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh ABSTRACT Sixteen sediment samples of different depth (up to 122 m) were studied by X-ray diffraction (XRD) method. The samples were collected from a test borehole, which was drilled by Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) at Kachua, Chandpur district. All the samples were characterized and different minerals have been identified in the samples. Quartz is the major mineral and was found to be in the range of 54.97 - 97.88 %. Two arsenic bearing minerals namely, iron arsenate, Fe2As(AsO4)3 and arsenic selenide telluride, AsSe0.5Te2 were found in the samples of depth 55.20 m and 100.60 m, respectively. Bangladesh Atomic Energy Commission (BAEC) in collaboration with the United States Geological Survey (USGS) conducted the groundwater sampling campaign for shallow and deep tubewells in Kachua upazila. From the hydro-chemical results, the concentrations of arsenic in shallow tubewells were found above the maximum permissible limit (50 ppb). Concomitantly, the mineralogical study of sediment samples in the same area reflects that the shallow aquifers of Kachua upazila are contaminated by arsenic due to the presence of arsenic bearing minerals. INTRODUCTION Clean drinking water supply is a basic requirement in primary health care in Bangladesh and groundwater is the dominant source of it. During the last 30 years about 4 million hand tubewells were installed in shallow aquifer to provide pathogen free drinking water.(1) Simultaneously, for self-sufficiency in food, the cultivation of high yielding variety of rice spread all over the country and large number of deep and shallow tube wells for irrigation were sunk. -

Sitakunda Upazila Chittagong District Bangladesh

Integrated SMART Survey Nutrition, Care Practices, Food Security and Livelihoods, Water Sanitation and Hygiene Sitakunda Upazila Chittagong District Bangladesh January 2018 Funded By Acknowledgement Action Against Hunger conducted Baseline Integrated SMART Nutrition survey in Sitakunda Upazila in collaboration with Institute of Public Health Nutrition (IPHN). Action Against Hunger would like to acknowledge and express great appreciation to the following organizations, communities and individuals for their contribution and support to carry out SMART survey: District Civil Surgeon and Upazila Health and Family Planning Officer for their assistance for successful implementation of the survey in Sitakunda Upazila. Action Against Hunger-France for provision of emergency response funding to implement the Integrated SMART survey as well as technical support. Leonie Toroitich-van Mil, Health and Nutrition Head of department of Action Against Hunger- Bangladesh for her technical support. Mohammad Lalan Miah, Survey Manager for executing the survey, developing the survey protocol, providing training, guidance and support to the survey teams as well as the data analysis and writing the final survey report. Action Against Hunger Cox’s Bazar for their logistical support and survey financial management. Mothers, Fathers, Caregivers and children who took part in the assessment during data collection. Action Against Hunger would like to acknowledge the community representatives and community people who have actively participated in the survey process for successful completion of the survey. Finally, Action Against Hunger is thankful to all of the surveyors, supervisor and Survey Manager for their tremendous efforts to successfully complete the survey in Sitakunda Upazila. Statement on Copyright © Action Against Hunger | Action Contre la Faim Action Against Hunger (ACF) is a non-governmental, non-political and non-religious organization. -

A Case Study of Brahmanaria Tornado Mdrezwan Siddiqui* and Taslima Hossain* Department of Geography and Environment, University of Dhaka, Yunus Centre, Thailand

aphy & N r at og u e ra G l Siddiqui and Hossain, J Geogr Nat Disast 2013, 3:2 f D o i s l a Journal of a s DOI: 10.4172/2167-0587.1000111 n t r e u r s o J ISSN: 2167-0587 Geography & Natural Disasters ResearchCase Report Article OpenOpen Access Access Geographical Characteristics and the Components at Risk of Tornado in Rural Bangladesh: A Case Study of Brahmanaria Tornado MdRezwan Siddiqui* and Taslima Hossain* Department of Geography and Environment, University of Dhaka, Yunus Centre, Thailand Abstract On 22 March 2013, a tornado swept over the Brahmanaria and Akhura Sadar Upazila (sub-district) of Brahmanaria district in Chittagong Division of Bangladesh and caused 35 deaths. There were also high levels of property damages. The aim of this paper is to present the geographical characteristics of Brahmanaria tornado and the detail of damages it has done. Through this we will assess the components at risk of tornado in the context of rural Bangladesh. Research shows that, though small in nature and size, Brahmanaria tornado was very much catastrophic – mainly due to the lack of awareness about this natural phenomenon. This tornado lasts for about 15 minutes and traveled a distance of 12 kilometer with an area of influence of 1 square kilometer of area. Poor and unplanned construction of houses and other infrastructures was also responsible for 35 deaths, as these constructions were unable to give any kind of protection during tornado. From this research, it has been seen that human life, poultry and livestock are mostly at risk of tornadoes in case of rural Bangladesh. -

Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 10 04 10 04

Geo Code list (upto upazila) of Bangladesh As On March, 2013 Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 BARISAL DIVISION 10 04 BARGUNA 10 04 09 AMTALI 10 04 19 BAMNA 10 04 28 BARGUNA SADAR 10 04 47 BETAGI 10 04 85 PATHARGHATA 10 04 92 TALTALI 10 06 BARISAL 10 06 02 AGAILJHARA 10 06 03 BABUGANJ 10 06 07 BAKERGANJ 10 06 10 BANARI PARA 10 06 32 GAURNADI 10 06 36 HIZLA 10 06 51 BARISAL SADAR (KOTWALI) 10 06 62 MHENDIGANJ 10 06 69 MULADI 10 06 94 WAZIRPUR 10 09 BHOLA 10 09 18 BHOLA SADAR 10 09 21 BURHANUDDIN 10 09 25 CHAR FASSON 10 09 29 DAULAT KHAN 10 09 54 LALMOHAN 10 09 65 MANPURA 10 09 91 TAZUMUDDIN 10 42 JHALOKATI 10 42 40 JHALOKATI SADAR 10 42 43 KANTHALIA 10 42 73 NALCHITY 10 42 84 RAJAPUR 10 78 PATUAKHALI 10 78 38 BAUPHAL 10 78 52 DASHMINA 10 78 55 DUMKI 10 78 57 GALACHIPA 10 78 66 KALAPARA 10 78 76 MIRZAGANJ 10 78 95 PATUAKHALI SADAR 10 78 97 RANGABALI Geo Code list (upto upazila) of Bangladesh As On March, 2013 Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 79 PIROJPUR 10 79 14 BHANDARIA 10 79 47 KAWKHALI 10 79 58 MATHBARIA 10 79 76 NAZIRPUR 10 79 80 PIROJPUR SADAR 10 79 87 NESARABAD (SWARUPKATI) 10 79 90 ZIANAGAR 20 CHITTAGONG DIVISION 20 03 BANDARBAN 20 03 04 ALIKADAM 20 03 14 BANDARBAN SADAR 20 03 51 LAMA 20 03 73 NAIKHONGCHHARI 20 03 89 ROWANGCHHARI 20 03 91 RUMA 20 03 95 THANCHI 20 12 BRAHMANBARIA 20 12 02 AKHAURA 20 12 04 BANCHHARAMPUR 20 12 07 BIJOYNAGAR 20 12 13 BRAHMANBARIA SADAR 20 12 33 ASHUGANJ 20 12 63 KASBA 20 12 85 NABINAGAR 20 12 90 NASIRNAGAR 20 12 94 SARAIL 20 13 CHANDPUR 20 13 22 CHANDPUR SADAR 20 13 45 FARIDGANJ -

Diversity of Cropping Systems in Chittagong Region

Bangladesh Rice J. 21 (2) : 109-122, 2017 Diversity of Cropping Systems in Chittagong Region S M Shahidullah1*, M Nasim1, M K Quais1 and A Saha1 ABSTRACT The study was conducted over all 42 upazilas of Chittagong region during 2016 using pre-tested semi- structured questionnaire with a view to document the existing cropping patterns, cropping intensity and crop diversity in the region. The most dominant cropping pattern Boro−Fallow−T. Aman occupied about 23% of net cropped area (NCA) of the region with its distribution over 38 upazilas out 42. The second largest area, 19% of NCA, was covered by single T. Aman, which was spread out over 32 upazilas. A total of 93 cropping patterns were identified in the whole region under the present investigation. The highest number of cropping patterns was 28 in Naokhali sadar and the lowest was 4 in Begumganj of the same district. The lowest crop diversity index (CDI) was observed 0.135 in Chatkhil followed by 0.269 in Begumganj. The highest value of CDI was observed in Banshkhali, Chittagong and Noakhali sadar (around 0.95). The range of cropping intensity values was recorded 103−283%. The maximum value was for Kamalnagar upazila of Lakshmipur district and minimum for Chatkhil upazila of Noakhali district. As a whole the CDI of Chittagong region was 0.952 and the average cropping intensity at the regional level was 191%. Key words: Crop diversity index, land use, cropping system, soybean, and soil salinity INTRODUCTION household enterprises and the physical, biological, technological and socioeconomic The Chittagong region consists of five districts factors or environments.