Great White Fleet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Itirst: Sfriowfltmg

I A THE SUNDAY ADVERTISER, NOVEMBER 28, 1909. ,41 THE TIME, THE PLACE, AND fcert. Miss Wilhelmina Tenney. Mr. M. will be her sister's matron of honor THE GIRL. E. Tenney, Miss Violet MeK-e- , Mr. and and little Maria Ealand will a.t as Mrs. C. HoMoway. Miss Carolina Brown fiower girl. Mrs. Sherman Stow wiil One night I went to a play that was '-- and Mr. Vernon Tennev. daughter into the t-i- . f give her groonj's rA.A tints' called . bride's cown is of fswii Time, Place, keeping. The "The the and the Girl." On Wednesday evening, at their home embroidered sheer India mus- And lattr, as homeward I took my way, oil Thurston avenue, Mr. and Mrs. Fred- and she wili wear My thoughts were in a whirl. lin and lace the erick K'anip entertained with a din- conventional veil. The inn ton of ner, followed by bridge The lin- For long ago I had chosen the Girl, whit. honor will wear an embroidered table decorations were carried out in costume, and Mrs. Stow s go But the Time, and the I'lace. oh dear; gerie a white and green, and eovers were laid is an imported creation of silver gray Each time that I dared to think of them for guests. dinner, I was strieken dumb with fear. fourteen After the duchesse satin. bridge was played untii a '.are hour. After the ceremony a wedding break- But after I saw that play, I thought Those present were Mr. and Mrs. Fred-frie- fast and reception wiil fo'luw at Tha Of several plans to try. -

Navy Captains Heavyweight Crew 1941 Lewis B

150th Anniversary Program Master of Ceremonies Robert Friedrich Director of Athletics Welcome Chet Gladchuk Superintendent Remarks Vice Adm. Ted Carter, USN Invocation Reverend Stanley Newton ‘85 Dinner 150th Anniversary Speakers Frank Shakespeare ‘53 Peter Bos ‘60 Tom Knudson ‘67 Dirk Mosis ‘73 Dan Lyons ‘81 Rear Adm. Heidi Berg ‘91 Dale Hurley ‘89 Kari Hughes ‘91 Jimmy Sopko ‘05 Fiona McFarland ‘08 Rick Clothier Adm. John Richardson ‘82 Navy Blue and Gold 150th anniversary of navy crew H 1 1869 Boat Club 1910’s In 1918 and 1919, as WWI drew to a close, Glendon’s crews began a run of success, twice winning the American Regatta Association Championship which was held in place of the Poughkeepsie Regatta in those years. The 1918 Championship was held in Annapolis, where Navy won on the home waters of the Severn. The following year, Navy recorded an undefeated sea- son en route to the championship in 1919. That same year, the lightweights debuted as Coach Glendon also brought a lightweight crew to the 1919 Championship, marking the first time that Navy competed in Lightweight crew. This first Navy Lights shell defeated Pennsylvania to win its inaugural race. 1920’s A year later, the championship regatta returned to Poughkeepsie. The 1920 Varsity suffered its only loss of the season there, to Syracuse, but rebounded to defeat the Orangemen in the National Regatta in Worcester, Mass., thus earning the right to represent the United States in the 1920 Olympics in Belgium. Navy rowed to the Olympic Gold Medal by driving past Great Britain in the final 500 meters. -

1899-1900 Obituary Record of Graduates of Yale University

® i V (/ (7 1 (T ftL OBITUARY RECORD OF GRADUATES OF TALE UNIVERSITY Deceased during the Academical year ending in JUNE, 1900, Including the Record of a few who died previously, hitherto unreported [PRESENTED AT THE MEETING OF THE ALUMNI, JUNE 26TH, 1900] [No 10 of the Fourth Printed Series, and No 59 of the whole Record] YALE COLLEGE (ACADEMICAL DEPARTMENT) 1828 OLIVER PAYSON HUBBARD, son of Stephen Hubbard, a mer- chant, and Zeruiah (Grosvenor) Hubbard, was born at Pomfret, Conn , on March 31, 1809 When he was two years of age the family removed to Rome, IS. Y., and from there he entered Ham- ilton College, but at the end of 1826 joined the Junior class at Yale. The year after graduation he taught in Geneva, N. Y, and the two years following in the Academy of O A. Shaw (Yale 1821) at Richmond, Va, and elsewhere. From 1831 to 1836 he was Prof. Silliman's assistant in the Chemical Laboratory of Yale College, where he aided Charles Goodyear in all those early exper- iments which led to his discovery of the process of vulcanizing India rubber. During these years he also made a report to the United States Government on the culture of sugar cane and man- ufacture of sugar in the Eastern States, and delivered a course of scientific lectures at Wesleyan University, Middletown. He was personally familiar with the earliest use of anaesthetics ID February, 1836, he was appointed Professor of Chemistry, Mineralogy and Geology at Dartmouth College, and filled that 660 chair for thirty years. -

The Philippines Digital Project

Deep Blue Deep Blue https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/documents Research Collections Library (University of Michigan Library) 2015 The Philippines Digital Project Scott, Blair https://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/113203 Downloaded from Deep Blue, University of Michigan's institutional repository Logistics of Project ● Questions/concerns about collections/archives to ask ○ Nature of source: Who is the author? What are they discussing? Is it primarily political, economic, or military history? How was this source acquired? Language? Date? etc. ○ Logistics: Was the institution or person affiliated helpful in finding this document? Is it easily accessible? Is it digitized? How did they find it/collect the document? Do they recommend any other collections/historical societies/archives? ● Website design ideas ○ Intended audience: Faculty/scholars, graduate students, undergraduate students (or enthusiasts) interested in Philippine history or conducting research on Philippine history under the American period ○ Goal: to provide an easily accessible, userfriendly web layout for such individuals to find Philippine sources in the state of Michigan (and other states mentioned in the work plan and learning objectives). Lessstudied/underutilized sources will be highlighted in the research guide to make it easier for such individuals to conduct research. ○ Ideas: ■ Some sort of map layout → state by state basis, zoom in and out feature, ability to use tags to find relevant docs. (ex. “women’s history”, “1950’s”, “U.S.Philippine relations”), basic map with list of states underneath (more userfriendly) ■ Simple list feature with tabs → Sort by state, then location/collection, then documents, sort of time period and topic of history ■ Complications could involve whether or not to include previews of docs. -

Dr. John Hubbard

COMMANDERS & CHIEFS Getting to know... John W. Hubbard, Ph.D. DR. JOHN HUBBARD TITLE: President and CEO COMPANY: Bioclinica Breaking Down Barriers to Innovation EDUCATION: Ph.D., Physiological Psychology and Physiology, University of Tennessee FAMILY: Wife of 36 years Dr. Hubbard has a history of breaking Positive. Resilient. down the barriers to innovation. HOBBIES: Martial Arts, 3rd Degree Black Belt While at Pfizer as senior VP and world- and senior instructor, international travel, home wide head of development operations, Dr. improvements, and gardening Hubbard directed and oversaw trial operations BUCKET LIST: Achieving his 4th Degree Black Belt and management of more than 450 clinical — Master Level and continuing to travel around projects a year and spearheaded initiatives to the world learning about different cultures improve the efficiency and productivity in pharma R&D. He served on the executive AWARDS/HONORS: Fellow, American College taskforce that redesigned Pfizer’s R&D orga- of Clinical Pharmacology (1994); Accomplished nization, which ultimately led to a significant Alumni Award, University of Tennessee (2009); improvement in quality and increase in pro- Distinguished Alumnus Award, Department of ductivity from 2010 to 2014. The challenges Psychology, Commencement Speaker, University of Pfizer faced were the need to reduce enterprise R&D costs by $2 billion, resolve a clinical Tennessee College of Arts & Sciences (2012); Fred warning letter, improve GCP data quality, J. Epstein M.D., Lifetime Achievement Award, 11th transition from multiple functional service Annual Dream & Promise Awards Benefit, Children’s providers to two global CROs, and deliver the Brain Tumor Foundation (2013); University of development portfolio on time and on budget. -

Jackson County, Kansas in the Spanish-American War 1898-1899

JACKSON COUNTY, KANSAS IN THE SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR 1898-1899 Compiled by Dan Fenton 2012 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: . 4 CHAPTER I: COMPANY D, 22nd KANSAS VOLUNTEER INFANTRY . .. 6 Roster of Company D, 22nd Kansas Volunteer Infantry. 8 CHAPTER II: OTHERS WHO SERVED: . 30 INDEX. 41 3 INTRODUCTION Sugar has been grown in Cuba since the 1500’s and it was one of the legs of a triangular slave trade between Africa, the Caribbean, and England or the United States. Slaves from Africa were brought to Cuba to work on the sugar plantations, the sugar or rum distilled from the sugar, was then exported to England or the United States, and from these places manufactured goods were sent to Africa in exchange for the slaves, who were shipped back to Cuba to work on the plantations. For four hundred years Cuba’s sugar trade flourished, and by the mid 1800’s, the United States was importing 80 percent of Cuba’s sugar production. Up until October 19, 1960 when the U. S. placed a trade embargo on Cuba, the island remained a strong trading partner of the United States, sugar and rum being Cuba’s largest exports to the States. The United States took a great interest in Cuba for business reasons, and at various times offered to buy the island from Spain. Over the years, Cuban rebels had fought Spain to gain independence for the island, and for the three years preceding 1898, the fighting was intense. Because of this unrest and the United States economic interests in Cuba, the U.S. -

On the Guemes Island Ferry, That Fall I Went Back to AHS in the Spring and Took a PG Course in Business Math and Typing

Lt William L. Maris, USN. (Ret) After graduating from HS in June 1938 and while still working part time as a “Deckhand” on the Guemes Island Ferry, that fall I went back to AHS in the spring and took a PG course in Business Math and typing. My Father and my Boss, decided it was time for me to get a real job (my Boss who had been a Chief Boatswain Mate in the Navy in WW-1), so off we went to the Navy Recruiting Office in Bellingham, WA. The Chief Petty Officer in Charge, asked Dad why he wanted me to join the Navy and Dad told the Chief there was no work in Anacortes and he was tired of feeding me so please sign me up! I was 20 years old the October 16th, 1939 and required my Fathers signature to Enlist. After getting the paper work done, four months on the waiting list, after we finally got a proper Birth Certificate with a “Gold Seal”, The Chief wouldn’t accept the Birth Certificates the State Statistics Office kept sending without the Seal on it. I ended up being 26 on the waiting list in the 13th Naval District. Around the first of December I received correspondence from the Naval Recruiting Office Seattle that I had been accepted and to report in to the Recruiting Office in the Federal Building in Seattle on 10 December 1939. After reporting in they logged me in and gave me a Voucher and sent me to the YMCA for dinner and berthing for the night and to report back to the Recruiting Officer at 0800 the next day. -

Maine Constitution. 1820

Maine State Library Maine State Documents Maine State Senate Legislature Documents 1820 Maine Constitution. 1820 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalmaine.com/senate_docs Recommended Citation "Maine Constitution. 1820" (1820). Maine State Senate. Paper 1. http://digitalmaine.com/senate_docs/1 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Legislature Documents at Maine State Documents. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine State Senate by an authorized administrator of Maine State Documents. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSTITUTION OF MAINE 1820 .. WE the people ofMaine, in order to establish justice, ensure Preamble. tranquillity, provide for our mutual defence, promote our common welfare, and secure to ourselves and our posterity the blessings of Liberty, acknowledging with grateful hearts the goodness of the Sovereign Ruler ofthe Universe in affording us an opportunity, so favorable to the design; and, imploring bis aid and direction in its accomplishment, do agree to form ourselves into a fi'ee and independent State, by the style and title of the State of lVlaine, and do ordain and establish the following Constitution for the government of the same. ARTICLE I. DECLARATION OF RIGHTS. SECT. 1. All men are born equally free and independent, and have certain natural, inherent and unalienable Rights, Natural ril!hts among which are those of enjoying and defending life and liberty, acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and of pursuing and obtaining safety and happiness. , SECT. 2. All power is inherent in the people; all free All powerinlie i' dd' h' h' d" di' entmthepe. governments are loun e 111 t ell' aut orlty an l11stltute lor pIe. -

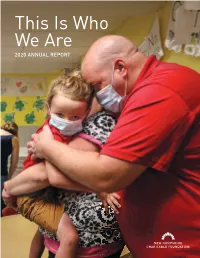

2020 ANNUAL REPORT This Is Who We Are

This Is Who We Are 2020 ANNUAL REPORT This Is Who We Are Who we are is never more apparent than that has thrown up barriers in front of We saw promising new models of with resources when they were most during times of crisis. Black and brown people since before this nonprofit news spring up to keep our desperately needed. We saw innovation, In New Hampshire in 2020, we saw republic was one. And we saw an ugly communities informed — and we saw ingenuity and breathtaking courage and people run toward the public health backlash — including threats of violence online echo chambers mutate with compassion. We saw heartbreak. And emergency, putting themselves at risk to and a move to censor teaching about our dangerous conspiracy fantasies. perseverance. And grace. care for their neighbors. And we saw people shared history. We saw people in the nonprofit sector Our communities face significant angrily protest the public health measures Despite a global pandemic, we saw roll up their sleeves and keep delivering challenges ahead. proven to slow the spread of disease. more people vote in a presidential election on their missions during a time of Here are 10 stories from a time We saw a new mobilization against and than had since 1964 — and we have sweeping illness and fear and uncertainty. of shared crisis that give us growing awareness of the systemic racism become less likely to trust our neighbors. We saw generous people come forward enduring hope. 2 3 We are critical infrastructure Devon and Morgan Phillips ran toward the emergency. -

Rev. John Hubbard

HISTORICAL SKETCH OF REV. JOHN HUBBARD OF MERIDEN, CONN. HIS ANCESTORS AND DESCENDANTS 1903 MERIDEN, CONN. THE HORTON PR1Nn"'G Co. 1930 PREFACE The following item is from the letter sent out by the secre tary, under date of October 15, 1929. At the annual meeting of the Hubbard family a committee was appointed to revise the Hubbard genealogy. This committee consists of Mr. Albert Wilcox, Mr. W. B. Rice, Mrs. Wilbur Chamberlain, all of Meriden, Conn., Miss Mary B. Hubbard of Wolfeboro, N. H. and our president, Mr; Harry B. Hubbard of West Haven, Conn. The committee has met and made preliminary plans. The contemplated book will include new material which has not yet been printed. PREFACE TO EDITION OF 1903 AT an annual meeting of the HUBBARD FAMILY it was voted that Miss ELLEN R. HouGH and ALBERT H. WILCOX be ap pointed a committee to collect material for the preparation of a history of our branch of the HUBBARD FAMILY. \,Ye here with submit the result. Vi/ e gratefully acknowledge the assist ance received from the works of the late EDMUND TUTTLE; also our obligations to HARLAN PAGE HuBBARD's "One Thou sand Years of Hubbard History," for information received. Also we wish to thank those friends who have assisted in the compilation of this book. So far as possible, each descendant from HoN. WILLIAM HUBBARD herein mentioned is numbered consecutively; and by carefully following these numbers any member may be readily traced backward or forward at pleasure. These same numbers are adopted in the biographical sketches, thus ena bling a ready reference from the genealogy to the biography. -

Lowell Vs. Faxon and Hawkes: a Celebrated Malpractice Suit in Maine James Alfred Spalding

Bangor Public Library Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl Books and Publications Special Collections 1910 Lowell vs. Faxon and Hawkes: A celebrated malpractice suit in Maine James Alfred Spalding Follow this and additional works at: https://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/books_pubs Recommended Citation Spalding, James Alfred, "Lowell vs. Faxon and Hawkes: A celebrated malpractice suit in Maine" (1910). Books and Publications. 53. https://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/books_pubs/53 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books and Publications by an authorized administrator of Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lowell vs. Faxon and Hawkes. A Celebrated Malpractice Suit in Maine. By James Alfred Spalding, M.D., Portla,;d, Me. Repri nt~d from the BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF MEDICINE Vol. XI. No. I. Febn1ary, 1910. LOWELL vs. FAXON AND HAWKES. A CELEBRATED MALPRACTICE SUIT IN MAINE. By J&MBS ALFRED SP&LDING, M.D., Portland, Maine.! Forty years ago the Maine Medical Association appointed a committee to investigate the legend, that ten years before, an important post-mortem examination .had been performed on the body of a man, who had suffered many years from an alleged dislocation of the hip joint. The idea in trying to obtain a re port of the examination was to discover information that might be of value to the profession in the diagnosis and treatment of such dislocation, in general, while additional interest attached to the case owing to the thirty-seven years that had elapsed since I the original injury. -

Genealogical Information from Chautauqua News, Sherman, Ny, 1879-1891 1

GENEALOGICAL INFORMATION FROM CHAUTAUQUA NEWS, SHERMAN, NY, 1879-1891 1 FULL NAME E DATE EVENT LOCATION COMMENTS PUBL DATE Abbey, Chauncey X recently Fitchburg, MA of Fredonia, on train involved in terrible accident; survived Apr 14,1886 Abbey, Mrs Chauncey D soon ? Fredonia ill; chances of recovery very slight;latest: trifle better May 19,1886 Abbott, Almon D Jul 09,1885 Westfield age 75; survived by wife and four children Jul 22,1885 Abbott, Charles X recently Panama of NYC, visited grandparents, M/M Ezra Abbott & aunt/G Windsor Jan 26,1887 Abbott, Cornelius M May 11,1884 Clymer of Mina Corners, and Eliza J Ballentine, Clymer;Rev D Carpenter May 21,1884 Abbott, Earl D last wk Sat Falconer in 75th year; prominent citizen Mar 20,1889 Abbott, Elizabeth(Miss) D Apr 09,1884 Corry, PA age 21;suicide by strychnine when deserted by Mr Spencer Apr 16,1884 Abbott, Ezra M Apr 29,1824 to Emelline Stewart; 60th at Panama; guests listed May 07,1884 Abbott, Ezra B Jan 28,1801 celebrated nintieth birthday at Panama Feb 11,1891 Abbott, Ezra (Dea) B Jan 28,1801 celebrated 88th;dau, Mrs Eliza Winslow was present Feb 06,1889 Abbott, Ezra (Dea) X Tuesday Panama returned from visit to daughter, Mrs George Windson, Jamestown Aug 06,1884 Abbott, Ezra (Dea) B Jan 28,1801 passed his 85th birthday at Panama Feb 10,1886 Abbott, Ezra (Deacon) B Jan 28,1802 88th B-day at Panama; dau, Mrs Eliza Winslow of Jamestown Feb 05,1890 Abbott, Ezra & wife X presently Panama are visitng their daughter, Mrs George Windson at Jamestown Nov 01,1882 Abbott, Ezra & Mrs X last week