Contracting out Schools at Scale: Evidence from Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secondary School Faqs

Secondary School FAQs Are you an independent school? OSH is a state school and we are very proud of this fact. It is one of 38 schools in the country that offer a boarding education within the state system. We share, with all good schools in the state and independent sectors, a belief in high standards of achievement and discipline and a commitment to providing an excellent education in the broadest sense. Why does the School have hospital in its name? The School was founded in the seventeenth century, when the term ‘hospital’ indicated a charitable institution rather than a medical one. Hospital meant ‘hospitality’, or board and lodging. We retain the traditional name as part of our unique heritage and because we are a boarding school. Do you have a catchment area? No, we welcome boys from all over the world as long as they have UK or EU/EEA nationality. What is a typical OSH pupil like? There is, of course, no such thing as a typical OSH pupil, but we are pleased that those who visit the School often comment on the genuine friendliness of our pupils and the fact that they are clearly very proud of their School. Can I visit the School and would I be able to meet staff? You are welcome to visit the School on any of our open events or by appointment. Depending on the timing of your visit you will have the opportunity to meet members of the Senior Leadership Team, teachers and boarding staff, who as a team are responsible for the education, safeguarding and welfare of OSH pupils. -

Great Start Readiness Program Classroom Requirements

CLASSROOM REQUIREMENTS Introduction Great Start Readiness Programs (GSRP) must comply with Public Act 116 of the Public Acts of 1973, as amended and the Licensing Rules for Child Care Centers. Michigan State Board of Education criteria for the GSRP require adherence to the Great Start Readiness Program Implementation Manual and the State School Aid Act requires program adherence to all standards in the Early Childhood Standards of Quality for Prekindergarten (ECSQ-PK). The Michigan Department of Education (MDE) requires grantees to address program quality in a systematic way utilizing both the applicable program evaluation tool and child outcome data. Agencies which operate GSRP must comply with state licensing regulations governing child care. GSRPs must receive a license from the Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs (LARA), Bureau of Community and Health Systems Child Care Licensing Division. All regular child use areas must be approved for use. Relocations must be completed with the knowledge of the Intermediate School District (ISD). The ISD and a GSRP Consultant must be notified within 24 hours of an incident being reported to licensing, of a special investigation being initiated, a change from a regular to a provisional license, or continued provisional status. For more information contact the Child Care Licensing Division at 866-685- 0006. This section provides detail and requirements for a high-quality, center-based preschool program that will enhance the development of young children. When even one child in a classroom is funded through GSRP, all GSRP guidelines must be followed: staff credentialing, curriculum, assessment, parent involvement, etc. Children in any classroom may be funded from a variety of sources, but all must attend for the full session. -

Full-Day Kindergarten? 2 Why Focus on State-Level Public Policy? 3 Four Key Areas Needed to Strengthen State Policy 4 1

FULL•DAY kindergarten A Study of State Policies in the United States Education Commission of the States © June 2005 by the Education Commission of the States (ECS). All rights reserved. Written by Kristie Kauerz. The Education Commission of the States is a nonprofit, nationwide organization that helps state leaders shape education policy. Copies of this publication are available for $10.00 plus postage and handling from the Education Commission of the States Distribution Center, 700 Broadway, Suite 1200, Denver, CO 80203-3460; 303.299.3692. Ask for No. EC-05-01. ECS accepts prepaid orders, MasterCard, American Express and Visa. All sales are final. ECS is pleased to have other organizations or individuals share its materials with their constituents.To request permission to excerpt part of this publication, either in print or electronically, please write or fax the Communications Department at the address above, fax 303.296.8332 or e-mail [email protected]. Please add postage and handling if your order totals: Up to $10.00, $3.00; $10.01-$25.00, $4.25; $25.01- $50.00, $5.75; $50.01-$75.00, $8.50; $75.01-$100.00, $10.00; over $100.01, $12.00. Generous discounts are available for bulk orders of single publications.They are: 10-24 copies, 10% discount; 25-49 copies, 20%; 50-74 copies, 30%; 75-99 copies, 40%; 100+ copies, 50%. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments iv Executive Summary v Introduction 1 Why Focus on Full-Day Kindergarten? 2 Why Focus on State-Level Public Policy? 3 Four Key Areas Needed To Strengthen State Policy 4 1. -

Pre-Kindergarten Programs an Overview and Comparison with Other States

Pre-kindergarten Programs An Overview and Comparison with Other States Introduction Efforts to move forward with a state funded preschool program in Washington came to fruition in 1985 when the state Legislature created a pre-kindergarten (pre-K) program called the Early Childhood Education and Assistance Program (ECEAP). Washington was in the forefront as having one of the first state financed preschool programs in the country. Currently, the state contracts with 40 local organizations to provide ECEAP. Head Start, also a preschool program, is federally funded and grants are presently given to 30 organizations in Washington to provide services. Both ECEAP and Head Start provide free high-quality pre- school education, family support, health, and nutrition services to children from low-income families or children who face circumstances that make it difficult for them to be ready for school. The Department of Early Learning (DEL), in partnership with the state Office of Financial Management, estimates that in 2010-11, ECEAP and Head Start were able to serve 46 percent of the Head Start eligible three and four-year-olds. A total of 23,900 eligible three and four- year-olds are not served and of these, 18,600 are eligible for ECEAP. Private preschools and kindergartens also operate and some are certified by the Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. In addition, there are licensed child care providers that offer kindergarten curriculum. Some institutions offer preschool that aligns with a particular approach, for example, Montessori or Waldorf schools. During the 2012 legislative session, SB 6449 and HB 2448 were introduced but did not pass. -

State of Ohio

STATE BOARD OF CAREER COLLEGES AND SCHOOLS 35 East Gay Street, Suite 403, Columbus, OH 43215-3138 (614) 466-2752 • Fax (614) 466-2219 • Toll Free (877) 275-4219 E-mail: [email protected] • Website: http://www.scr.ohio.gov/ The Honorable Bob Taft, Governor of Ohio; Members of the General Assembly; Administrators of Registered Schools: This report is filed in compliance with Ohio Revised Code Sections 149.01 and 3332.031(N). We attest that the information contained herein is an accurate reflection of the activities of this State Board of Career Colleges and Schools (Formerly known as the State Board of Proprietary School Registration), as well as the career colleges and schools registered by the Board, during fiscal year 2004. This is the 30th Annual Report produced by this Board. Ohio has one of the largest career education systems in the country. The State Board of Career Colleges and Schools is responsible for monitoring and regulating approximately 270 for-profit and non-profit private career colleges and schools in the State of Ohio. During fiscal year 2004, these private career schools educated over 60,000 students in 1,600 programs approved by this Board. The State Board of Career Colleges and Schools continues to work to assure that career education succeeds for the citizens of Ohio. It is our hope that this Annual Report will provide insight for the citizens of Ohio about the significant, positive contributions of private career colleges and schools in Ohio. On behalf of the State Board Career Colleges and Schools , we hope that you will find our Annual Report informative and enlightening. -

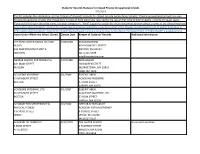

Students' Records Statuses for Closed Private Occupational Schools 7/2

Students' Records Statuses for Closed Private Occupational Schools 7/2/2019 This list includes the information on the statuses of students' records for closed, private occupational schools. Private occupational schools are non- Private occupational schools that closed prior to August 2012 were only required by the law at that time to hold students' records for seven years; If you don't find your school by name, use your computer's "Find" feature to search the entire document by your school's name as the school may have Information about students' records for closed degree-granting institutions may be located at the Massachusetts Department of Higher Education is Information about students' records for closed hospital-based nursing programs may be located at the Department of Public Health is available here. Name Under Which the School Closed Closure Date Keeper of Students' Records Additional Information 7TH ROW CENTER HANDS-ON! CAR 7/28/2008 KEVAN BUDROW AUDIO 60 BLOOMFIELD STREET 325 NEW BOSTON ST UNIT 6 BOSTON, MA 02124 WOBURN (617) 265-6939 [email protected] ABARAE SCHOOL FOR MODELING 4/20/1990 DIDA HAGAN 442 MAIN STREET 18 WARREN STREET MALDEN GEORGETOWN, MA 01833 (508) 352-7200 ACADEMIE MODERNE 4/1/1989 EILEEN T ABEN 45 NEWBURY STREET ACADEMIE MODERNE BOSTON 57 BOW STREET CARVER, MA 02339 ACADEMIE MODERNE, LTD. 4/1/1987 EILEEN T ABEN 45 NEWBURY STREET ACADEMIE MODERNE, LTD. BOSTON 57 BOW STREET CARVER, MA 02339 ACADEMY FOR MYOTHERAPY & 6/9/1989 ARTHUR SCHMALBACH PHYSICAL FITNESS ACADEMY FOR MYOTHERAPY 9 SCHOOL STREET 9 SCHOOL STREET LENOX LENOX, MA 01240 (413) 637-0317 ACADEMY OF LEARNING 9/30/2003 THE SALTER SCHOOL No records available. -

1 Reform Options for Britain's Private Schools Contents

Reform Options for Britain’s Private Schools Contents: - Executive Summary (p.1) - Reform Options table (p.2-3) - About Private School Policy Reform (p.4) - Acknowledgements (p.4) - Sections: (1) Introduction (p.5) (2) Reform Options (p.6-19) (3) Further practical questions (p.20-23) - Conclusion (p.23) - Book list (p.24) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY There is increasing concern that the enormous school resources gap – upwards of three to one – between pupils in private schools and those in state schools represents a skewed and inefficient use of our educational resources. Critics have pointed to a democratic deficit as many political, business and civil leaders continue to be exclusively privately educated, despite only 7 per cent of pupils being privately educated. There is a sense beneficiaries of a private education may have only limited understanding of state education and the majority of Britons who attend them. There is also evidence a majority of the public think the private school advantage in Britain is unfair. Yet we know politicians of all parties have not addressed this problem for decades. Now is the time for change. This report, for the benefit of today’s policy-makers, presents six feasible options for resolving Britain’s private school question. These options vary in their potential to bring about substantial reform. We also outline the practical issues surrounding each, together with the approximate financial implications for the government’s schools budget. Some combinations of options are also possible, which we discuss after looking at them individually. The first five all involve an imposed change: taxation of school fees, removing private schools’ charitable status, contextual admissions to universities and job recruitment, partial integration with the state school system, and nationalisation. -

How to Transfer to an Out-Of-State Or Private School College Or University

How to Transfer to an out-of-state or private school college or university There are unique challenges to transferring from Palomar College to a private or out-of-state school with whom there are no official course to course agreements. Because there are thousands of colleges and universities it would be impossible to have articulation agreements with them all. However, it is possible to transfer to one of these schools. It requires more effort to research the school’s pertinent information and places more responsibility on the student to understand and complete the requirements to transfer for that specific school. First, research the school’s catalog and website. Locate the information that addresses the admissions requirements for transfer students. It is important to find out: 1. the minimum number of transfer level units required 2. any minimum course requirements (such as English or math) 3. when applications and transcripts are due 4. if additional exams such as a SAT are required 5. if there are any special conditions required for out-of-state applicants 6. what courses are transferable. Some schools will have limits as to how many units can be transferred in or disallow certain requirements to be met from outside their school Second, identify the tuition. If you are trying to transfer out-of-state you need to be aware that you will likely be charged the higher non-resident tuition rate if it is a public university. In most cases, just moving to a new state will not entitle you to in-state tuition rates (for at least a period of time). -

Full-Day Kindergarten: a Look Across the States EMILY PARKER, LOUISA DIFFEY and BRUCE ATCHISON

SEPT 2016 DIG IN. 50-STATE Discover how states approach priority REVIEW education issues. Full-Day Kindergarten: A look across the states EMILY PARKER, LOUISA DIFFEY AND BRUCE ATCHISON Research indicates that a high- many are also looking to establish quality, full-day kindergarten quality full-day kindergarten to In 28 STATES, the experience is a crucial component support the gains made in the pre-K length of full-day to setting students up for ongoing space and to set students up for kindergarten (whether it academic success, yet vast success throughout their academic is required or optional) differences exist in the quality of careers. This report explores the spectrum of full-day kindergarten is equal to that of first programs and highlights different grade length of day. IN 13 STATES models of funding implemented PLUS THE DISTRICT OF by states. Additionally, it examines COLUMBIA, DISTRICTS ARE the requirements for full-day kindergarten, including state bans on REQUIRED TO OFFER FULL- The DEFINITION of parent tuition and the length of day DAY KINDERGARTEN. full-day, and the level for full-day kindergarten. at which the program is funded, varies kindergarten programs and how they are funded across the states.1 As considerably from state states continue to develop strong to state. pre-kindergarten (pre-K) programs, www.ecs.org | @EdCommission 2 Where is Full-Day Kindergarten Required? While 13 states plus the District of Columbia (D.C.) (see Figure 1) require full-day kindergarten, the definition of full-day, and the level at which the program is funded, varies from state to state. -

Man Being Interviewes; Ayman Ayman's Story I

I: Woman interviewing A: Man being interviewes; Ayman Ayman’s story I: Hello Ayman. A: Hello. Hi, Linda. I: You’ve got quite an unusual name, haven’t you? Where do you Come from? A: That’s right. My name is Ayman and I’m aCtually British. I: Okay. A: However, I have an Egyptian father. I: Were you born in Egypt or were you born in the U.K.? A: Actually, I was born in England. I was born in a City Called LeiCester, in the Midlands, and as I grew up, my father worked in various Countries around the world. So as a youngster I travelled quite a bit. I: Did you? How old were you the first time you went abroad? A: The first time I went abroad I was six years old and we moved to the Middle East. I: Whereabouts in the Middle East? A: We moved to a Country Called Oman. I: And did you go to a sChool, an ordinary state sChool in Oman, or did you go to some kind of international sChool? A: We went to a private sChool whiCh was espeCially there for Children of parents Coming from overseas. So it was an international junior school. I: Was it a big school? A: Yeah, it was a fair size. We were about 250 students, whiCh for a small Country like Oman was quite big. 1 I: That’s quite a lot. Were you mainly with British or AmeriCan kids or was it a mixture of all sorts of nationalities? A: It was a real mix. -

New York State Reopening Guidance for Religious and Independent Schools

New York State Reopening Guidance for Religious and Independent Schools July 27, 2020 STATE OFFICE OF RELIGIOUS AND INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS NEW YORK STATE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT | ALBANY, NEW YORK TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 2 Communication/Family and Community Engagement ............................................................ 6 Health and Safety .......................................................................................................................... 7 Facilities Guidance ..................................................................................................................... 10 Child Nutrition ............................................................................................................................. 14 Transportation Guidance ........................................................................................................... 20 Social Emotional Well-Being ..................................................................................................... 24 Religious and Independent School Schedules ....................................................................... 32 Attendance ................................................................................................................................... 34 Teaching and Learning .............................................................................................................. 36 -

Assessment in Schools in Pakistan

SA-eDUC JOURNAL Volume 9, Number 2 September 2012 Assessment in schools in Pakistan Shamaas Gul Khattak1 School of Arts and Education, Middlesex University (London) [email protected] Abstract This study scrutinises the examination and assessment system in schools in Pakistan that is applicable from primary through to secondary education (Year X). It begins with a brief background of the Pakistani examination system established by its colonial masters; it then describes the present education system with special reference to the assessment process of students. An overview of the curriculum development and curriculum reforms in the country expands our understanding of the moribund assessment system in state schools. The primary focus of the study is to contextualise the assessment system in primary and secondary education and to assess the present rectification measures being put in place by the education authorities. Historical background of the examination system in Pakistan Pakistan is governed under the Islamic, Democratic, Federal Constitution of 1973 and the governance extends to four autonomous provinces: Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Pukhtunkhwah and Baluchistan. Education in Pakistan is essentially a provincial affair; however, certain educational functions are the responsibility of the Federation via the Federal Ministry of Education. Examinations in Pakistan are a legacy of the past, inherited from the British system. Following the model of the University of London, an external final examination, called matriculation was instituted at the end of the high school stage in the 1880s (Shirazi, 2004). It was initially administered by the London University. After the establishment of universities in Bombay, Calcutta and Madras in the 1857 the matriculation examination was conducted by these universities.