Dryocopus Lineatus (Lineated Woodpecker)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trip Report February 12 – 21, 2020 | Written by Dodie Logue

Southern Belize: Pristine & Wild | Trip Report February 12 – 21, 2020 | Written by Dodie Logue With Guide Dodie Logue, and participants Dennis, Helen, Kay, Hayden, Judy, Tony, Christine, Larry, Carol, Jamie, Ellen, Naturalist Journeys, LLC | Caligo Ventures PO Box 16545 Portal, AZ 85632 PH: 520.558.1146 | 866.900.1146 Fax 650.471.7667 naturalistjourneys.com | caligo.com [email protected] | [email protected] Wed., Feb. 12 Early arrivals | Transfer to Crooked Tree | Pre-extension Today most of the group arrived; some had come in a day or two earlier on their own. There were airport shuttles and getting situated in the two lodges, Crooked Tree and Beck’s, which were just over a mile apart. Some of the earlier arrivals had a little time to bird the grounds of their lodge. Crooked Tree Village is a small area, NW of Belize City, about 45 minutes by car. The residents rely on tourism, as well as fishing and farming, for their livelihood. Crooked Tree Wildlife Sanctuary was established in 1984 and is run by Audubon. It encompasses around 25 square miles of government-sanctioned land, including freshwater lagoons, savannah, and broadleaf and pine woods. Some of the birds seen right on the grounds for the early arrivals were Black- cowled Oriole, Red-lored Parrot, and Lineated Woodpecker. There were two airport shuttles to pick up the various arrivals, and at 6:30 PM we all met as a group in the dining room at Beck’s for a meal of coconut curry fish, herbed chicken, and rice and beans. Hearty and delicious! Most were tired from a long travel day and, knowing about the early departure the next morning, we all went off to our lodges and were soon tucked in. -

ON 1196 NEW.Fm

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 25: 237–243, 2014 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society NON-RANDOM ORIENTATION IN WOODPECKER CAVITY ENTRANCES IN A TROPICAL RAIN FOREST Daniel Rico1 & Luis Sandoval2,3 1The University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska. 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Windsor, 401 Sunset Avenue, Windsor, ON, Canada, N9B3P4. 3Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San Pedro, San José, Costa Rica, CP 2090. E-mail: [email protected] Orientación no al azar de las entradas de las cavidades de carpinteros en un bosque tropical. Key words: Pale-billed Woodpecker, Campephilus guatemalensis, Chestnut-colored Woodpecker, Celeus castaneus, Lineated Woodpecker, Dryocopus lineatus, Black-cheeked Woodpecker, Melanerpes pucherani, Costa Rica, Picidae. INTRODUCTION tics such as vegetation coverage of the nesting substrate, surrounding vegetation, and forest Nest site selection play’s one of the main roles age (Aitken et al. 2002, Adkins Giese & Cuth- in the breeding success of birds, because this bert 2003, Sandoval & Barrantes 2006). Nest selection influences the survival of eggs, orientation also plays an important role in the chicks, and adults by inducing variables such breeding success of woodpeckers, because the as the microclimatic conditions of the nest orientation positively influences the microcli- and probability of being detected by preda- mate conditions inside the nest cavity (Hooge tors (Viñuela & Sunyer 1992). Although et al. 1999, Wiebe 2001), by reducing the woodpecker nest site selections are well estab- exposure to direct wind currents, rainfalls, lished, the majority of this information is and/or extreme temperatures (Ardia et al. based on temperate forest species and com- 2006). Cavity entrance orientation showed munities (Newton 1998, Cornelius et al. -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

The Lineated Woodpecker

THE LINEATED WOODPECKER BY RICHARD R. GRARER SSENTIALLY a bird of tropical lowlands, the Lineated Woodpecker (Dryo- E copus lineatus) also occurs as high as 5000 feet in Mexico and 3600 feet in El Salvador. In Tamaulipas and San Luis Potosi, I have seen it in scrubby growth, but fairly mature forest seems to be the favored habitat. It will be interesting to see how this species survives increasing deforestation in Mexico. Fortunately it has a broad range, from southeastern Sonora and southern Tamaulipas, Mexico, to northern Argentina. Over this range it varies considerably in size, plumage, and color of soft parts. Bill and eye color also vary with age. Dickey and van Rossem (1938. 2001. Ser. Field Mus. Nat. Hist., 28:311) noted the bill of a juvenile from El Salvador as “bluish-horn color, tip paler,” and of adults as “ivory-white be- coming bluish at the base of the maxilla and on basal third of mandible.” The iris of the juvenile was “dark brown,” and of adults “bluish white.” A similar change in eye-color with age occurs in the Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocop~~ pileatus) . In northern Argentina, Wetmore (1926. U.S. Natl. Mus. Bull., 133: 216) found the bill of an adult male Lineated Woodpecker to be “pale smoke gray” and the iris “dull white.” Sexual dimorphism in this species also re- sembles that in the Pileated Woodpecker, males having the mustache‘ ’ marks and entire crown red. The loud, high pitched cries of Lineated Woodpeckers in Mexico are remi- niscent of the Pileated. However the birds must be versatile vocally, since Wetmore (1943. -

Black Phoebe Habitat: GUIDE(Sayornis Nigricans) Possibly Found Along the River Behind the Bamboo

LOCAL BIRD Diagnostic: Flycatcher that is all black except for its white belly, almost always near water. Has a slight crest. Black Phoebe Habitat: GUIDE(Sayornis nigricans) Possibly found along the river behind the bamboo. Diet: Perches near the river to glean insects. Call: High, squeaky phibii. TOP FEATURED RESIDENT BIRDS Black Phoebe (Sayornis nigricans).................................................................................................3 Black Vulture (Coragyps atratus)....................................................................................................4 Blue-and-white Swallow (Pygochelidon cyanoleuca).................................................................5 Blue-gray Tanager (Thraupis episcopus)......................................................................................6 Clay-colored Thrush (Turdus grayii).................................................................................................7 Gray Hawk (Buteo plagiatus) ..........................................................................................................9 Grayish Saltator (Saltator coerulescens).....................................................................................10 Great Kiskadee (Pitangus sulphuratus)........................................................................................11 Great-tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus).............................................................................12 Inca Dove (Columbina inca)...........................................................................................................14 -

Threatened Birds of the Americas

HELMETED WOODPECKER Dryocopus galeatus V/R10 Records of this rare woodpecker are confined to primary tracts of Atlantic Forest in southern south-east Brazil, eastern Paraguay and northernmost Argentina, where there have been many records in very recent years. It still, however, requires urgent study and survey using voice playback, to clarify its status and ecological niche. DISTRIBUTION The Helmeted Woodpecker is endemic to the southern Atlantic (Paranense) Forest region of south-east Brazil, eastern Paraguay and north-east Argentina (Misiones). In the following account, records are listed from north to south with coordinates taken, unless otherwise stated, from Paynter (1985, 1989) and Paynter and Traylor (1991). Brazil The species is known from São Paulo, Paraná, Santa Catarina and at least formerly Rio Grande do Sul, but it is noteworthy that it has been recorded from two and possibly all three frontier areas of southernmost Mato Grosso do Sul (Porto Camargo in easternmost Paraná, Capitán Bado in westernmost Concepción, Paraguay, and possibly the Sierra de Maracaju, northernmost Canindeyú, Paraguay), indicating that it might yet be (or once have been) found in the state. São Paulo Records are from: Rio Feio, 21°26’S 50°59’W, 1901 (Pinto 1938); Ribeirão Caingang (“Ribeirão dos Bugres”), 21°40’S 51°32’W, April 1901 (Pinto 1938); Vitoriana (“Victoria”), April 1902 (specimen in AMNH); “Aracuahy” mountain near Ipanema, April, May, June and December in the years 1819-1822 (von Pelzeln 1868-1871); Rio Carmo road, Fazenda Intervales, 850 m, 24°17’S 48°25’W, near Capão Bonito, February 1987 (Willis 1987); Iguape, October 1901 (Pinto 1938), this presumably the locality specified as Baurú in von Ihering and von Ihering (1907); Carlos Botelho State Park, 900 m, November 1988 (C. -

Habits of the Crimson-Crested Woodpecker in Panama

HABITS OF THE CRIMSON-CRESTED WOODPECKER IN PANAMA LAWRENCE KILHAM studied the Crimson-crested Woodpeckers (Campephilus [ Phloeoceastes] I melanoleucos) in the Panama Canal Zone in February 1965 and from November 1970 to February 1971, a period which included the end of the rainy season when nesting began and the onset of the dry season when young were nedged. The behavior of this species resembles that described by Tanner (1942) for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principal&) and has not hitherto been the subject of any detailed reports, with exception of notes by Short (1970b), as far as I am aware. In Shorts’ opinion (1970a), Phloeoceastes should be merged in Campephilus and I have adopted this terminology. While the aim of present studies was to learn as much as possible about the total behavior of C. melanoleucos, the problems raised by its similarity in size and coloration to the sympatric Lineated Woodpecker (Dryocopus Zineatus) were kept in mind, thanks to the ideas of Cody (1969) on why this parallelism exists. Actual field observations, however, failed to support his interesting theories, which are dealt with in greater length in a final discussion. STUDY AREAS I studied Crimson-crested Woodpeckers in five localities of which three, Madden Forest Reserve, Limbo Hunt Club, and Barro Colorado Island (BCI), were, for the most part, mature forests. Of the other two areas, one was of second growth forest 10 to 20 m in height at Cardenas Village where I lived and the other at Frijoles, an area under partial cultivation opposite Barro Colorado Island. The Crimson-crested and Lineated Wood- peckers were sympatric in all five of these localities, as indeed they are in much of South America. -

TOP BIRDING LODGES of PANAMA with the Illinois Ornithological Society

TOP BIRDING LODGES OF PANAMA WITH IOS: JUNE 26 – JULY 5, 2018 TOP BIRDING LODGES OF PANAMA with the Illinois Ornithological Society June 26-July 5, 2018 Guides: Adam Sell and Josh Engel with local guides Check out the trip photo gallery at www.redhillbirding.com/panama2018gallery2 Panama may not be as well-known as Costa Rica as a birding and wildlife destination, but it is every bit as good. With an incredible diversity of birds in a small area, wonderful lodges, and great infrastructure, we tallied more than 300 species while staying at two of the best birding lodges anywhere in Central America. While staying at Canopy Tower, we birded Pipeline Road and other lowland sites in Soberanía National Park and spent a day in the higher elevations of Cerro Azul. We then shifted to Canopy Lodge in the beautiful, cool El Valle de Anton, birding the extensive forests around El Valle and taking a day trip to coastal wetlands and the nearby drier, more open forests in that area. This was the rainy season in Panama, but rain hardly interfered with our birding at all and we generally had nice weather throughout the trip. The birding, of course, was excellent! The lodges themselves offered great birding, with a fruiting Cecropia tree next to the Canopy Tower which treated us to eye-level views of tanagers, toucans, woodpeckers, flycatchers, parrots, and honeycreepers. Canopy Lodge’s feeders had a constant stream of birds, including Gray-cowled Wood-Rail and Dusky-faced Tanager. Other bird highlights included Ocellated and Dull-mantled Antbirds, Pheasant Cuckoo, Common Potoo sitting on an egg(!), King Vulture, Black Hawk-Eagle being harassed by Swallow-tailed Kites, five species of motmots, five species of trogons, five species of manakins, and 21 species of hummingbirds. -

Species List January 13 – 20, 2018│Compiled by Bob Meinke with Pacific Coast Extension | January 20 – 24

Costa Rica: Birding and Nature│Species List January 13 – 20, 2018│Compiled by Bob Meinke With Pacific Coast Extension | January 20 – 24 Guides Willy Alfaro and Bob Meinke, with expert local lodge naturalists and 12 participants: Tom, Kristy, Julie, Charlie, Sheila, Pierre, Elisabeth, Beverly, Ellen, Judy, Kurt, and Lea Summary Surprisingly cooler than average weather offered pleasant temperatures during our travels (it was never hot), and despite the drizzle and occasional downpour (due to an unusual lingering into January of the Central American rainy season), we saw many species of birds, including rare and elusive taxa such as Chiriquí and Buff- fronted Quail-Doves (both local endemics), the recently described Zeledon’s Antbird, Spotted Wood-Quail, the aptly named Tiny Hawk, Fasciated Tiger-Heron, and the cryptic Scaled Antpitta. Stars among the 24 species of hummingbirds recorded on the trip were Black-crested Coquette, the unique Snowcap, and Volcano, Scintillant, and Fiery-throated Hummingbirds (the latter four species regional endemics). Among the visually more impressive birds we encountered were Great Green Macaw, Cinnamon Woodpecker, Collared Trogon, Jabiru, the endemic Golden-browed Chlorophonia, Emerald Tanager, and four species of Motmot. Unlike many birds that reside in North America, Neotropical species seem largely undaunted by mist and rain, and we had little trouble racking up impressive observations during the main trip, as well as on the Pacific coast extension. The combined list below summarizes main tour and Pacific coast post-tour extension sightings, covering species seen by all or at least some of the participants. Those observed only by the “extension group” (i.e., Elisabeth, Pierre, Lea, Judy, Sheila, and Charlie), including many shorebirds and waders not seen during the main tour, are differentiated below by RED text. -

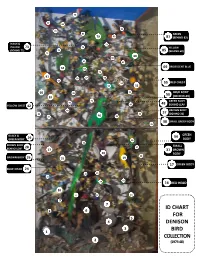

Identification Chart for Denison Bird Collection

78 77 84 82 76 83 GREEN 79 80 81 (BEHIND 82) BLACK & 71 YELLOW 73 72 YELLOW (BEHIND 72) 74 85 (BEHIND 68) 75 68 66 65 67 IRIDESCENT BLUE 64 63 69 70 61 58 57 56 62 54 55 RED CHEST 53 52 51 BLUE BODY 60 46 50 59 (BEHIND 49) 41 GREEN BODY 45 48 YELLOW CHEST 42 49 BEHIND LEAF 43 BROWN BODY 44 36 37 (BEHIND 36) 47 40 39 38 SMALL GREEN BODY 35 BLACK & GREEN 29 34 GREEN BODY 33 BODY 30 BROWN BODY SMALL 28 32 BEHIND LEAF 27 31 BROWN 20 BODY 18 BROWN BODY 26 25 19 17 GREEN BODY BLUE HEAD 24 22 21 23 15 14 16 RED HEAD 10 11 12 13 9 7 ID CHART 8 6 FOR 5 4 DENISON 3 BIRD 1 COLLECTION 2 (1979.48) CONSERVATION NUMBER BIRD SPECIES NATIVE REGION REFERENCE STATUS* 1 Hooded Merganser New England LC 2 Virginia Rail Americas LC IUCN Red List 3 Clapper Rail Americas LC IUCN Red List 4 California Quail Americas LC 5 Horned Lark North America LC Greenman 6 Lineated Woodpecker Central and South America LC 7 Wood Duck Americas LC 8 9 Turquoise Tanager South America LC whatbird.com Forum 10 Black Throated Magpie Jay Mexico LC whatbird.com Forum 11 Woodcreeper Central and South America whatbird.com Forum 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Pompadour Cotinga South America LC whatbird.com Forum CONSERVATION NUMBER BIRD SPECIES NATIVE REGION REFERENCE STATUS* 21 22 23 24 25 Green-and-Black Fruiteater South America LC whatbird.com Forum 26 27 Eurasian Jay Europe and Asia LC whatbird.com Forum 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 White-Bibbed Manakin (possibly) Central America LC whatbird,com Forum 37 38 39 40 Quetzal South America NT IUCN Red List CONSERVATION NUMBER BIRD SPECIES NATIVE -

A Natural Systems Glossary

A NATURAL SYSTEMS GLOSSARY A Glossary of Environmental, Biological, Zoological, Botanical, Ecological, Biogeographical, Evolutionary, Taxonomic, Hydrologic, Geographic, Geomorphologic, Geophysical and Meteorological Terms March 2006 (last revised May 2008) INTRODUCTION This glossary is the outgrowth of the InkaNatura guide training workshop held at Sandoval Lake Lodge and the Heath River Wildlife Center in southeastern Peru and adjacent Bolivia in January and February 2006. It began with the list of approximately 300 vocabulary words and terms generated during the workshop as well as many additional words and terms generated during the January and February 2008 guide training workshop held at Cock-of-the-Rock Lodge and Manu Wildlife Center in southeastern Peru. While originally intended for the use of the InkaNatura guides, it has expanded into a reasonably comprehensive glossary in excess of 2700 terms and useful throughout North and South America. This version of the glossary should only be considered a draft. It has been compiled from many books and online sources. Some entries I wrote myself but the vast majority were cut and pasted from the many online and printed sources. In future versions the definitions will be edited down, but in this version, in the interest of time, for a large number of the entries several definitions from multiple sources have been included. Throughout the glossary, words and terms in boldface type indicate other entries in the glossary. GLOSSARY abdomen - The part of the body that generally contains the intestines; also called the belly; in organisms, such as insects and spiders, is the last body section…In entomology, the part of an insect’s body that contains the digestive system and the organs of reproduction. -

Annotated Bird Species List Reader Rendezvous Costa Rica Part II - 7Th-14Th January 2020 Compiled by Raymond L

Annotated Bird Species List Reader Rendezvous Costa Rica Part II - 7th-14th January 2020 Compiled by Raymond L. VanBuskirk based on field notes, eBird lists, and paper checklists. Birds of Costa Rica’s Central Valley and Pacific Slope 1. Great Tinamou - one (or maybe multiples) heard singing on the forested slopes at Carara NP 2. Black-bellied Whistling-Duck - Many large groups seen roosting in the trees on the Tarcoles River Boat Trip 3. Muscovy Duck - Multiple large flocks seen in-flight near the end of the Tarcoles River Boat Trip. 4. Blue-winged Teal - Small flock on the Tarcoles River Boat Trip 5. Gray-headed Chachalaca - Our best views of this species were of a small flock feeding in the treetops outside of the breakfast room at Ficus Lodge. 6. Crested Guan - Seen twice during the trip; once by a small group of birders in the morning at Villa Lapas and later, by the whole group, on the trails at Curi-Cancha Preserve near Monteverde. 7. Black Guan - found only in the mountains of Costa Rica and Panama this regional endemic was seen by some at the Monteverde Skywalk Bridges. 8. Rock Pigeon - Rock Pigeons were seen. What else is there to say? 9. Red-billed Pigeon - These giant, small headed pigeons were seen on the first two days of the trip, with the best views being of individuals at Hotel Villa Lapas. 10. Short-billed Pigeon - Identified first by voice singing “who cooks for you” in the mornings at Hotel Villa Lapas and was subsequently seen in the tops of a fruiting cecropia tree on the hotel grounds.