Development of Interior Landmark Designation Policies in Washington , D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Foreign Service Journal, June 1962

A In This Issue The Modernization Process and Insurgency, by Henry C. Ramsey JUNE 7962 Since men began living together in organized societies, leaders have recognized a potent factor governing any action they may be about to undertake. The Romans called it vox populi. We still use the classic Latin phrase when referring to "the expressed opinion of the people" For many years, in over 100 countries, the people have been expressing their opinion of Seagram’s V.O. Canadian Whisky, with its true lightness of tone and its rare brilliance of taste. It is an enthusiastically positive opinion with a measureable effect: throughout the world more people buy A CANADIAN ACHIEVEMENT HONOURED THE WORLD OVER The Foreign Service Journal is the professional journal of the American For¬ FORSTGF^^^|JOURNAL eign Service and is published by the American Foreign Service Association, a non¬ profit private organization. Material appearing herein represents the opinions of rtJPUBLISHEO MONTHLY BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION X-f~l the writers and is not intended to indicate the official views of the Department of State or of the Foreign Service as a whole. AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION CHARLES E. BOHLEN, President TYLER THOMPSON, Vice President JULIAN F. HARRINGTON, General Manager CONTENTS JUNE 1962 Volume 39, No. 6 BARBARA P. CHALMERS, Executive Secretary BOARD OF DIRECTORS HUGH G. APPLING, Chairman H. FREEMAN MATTHEWS, JR., Secretary-Treasurer page TAYLOR G. BELCHER ROBERT M. BRANDIN MARTIN F. HERZ 21 THE MODERNIZATION PROCESS AND INSURGENCY HENRY ALLEN HOLMES by Henry C. Ramsey THOMAS W. MAPP RICHARD A. POOLE 24 THE BAR-NES COROLLARY TO PARKINSON’S LAW ROBERT C. -

On R.O.T.C. Request the Executive Council of the Posal That Would Establish "The Army R.O.T.C

Vol. LVII, No.4 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D.C. Friday, September 21, 1973 ExCo Delays Decision On R.O.T.C. Request The Executive Council of the posal that would establish "the Army R.O.T.C. Director Col. School of Foreign Service Tues Departments of Army and Air Albert Loy and Air Force Direc· day delayed a decision on aca Force Reserve Officer Training tor Lt. Col. Charles Karczewski . demic credit and departmental under the supervision of the Dean requested academic credit and status for Army and Air Force of the School of Foreign Service." departmental status for their units R.O.T.C. units. The proposal also called for the after a July decision of the Foreign Service Dean Peter council to approve "a minimum University's Board of Directors. Krogh appointed a sub-com of six credits of free electives The board ruled that R.O.T.C. mittee to study the issue. The toward degree requirements for instructors could not be on active sub-committee will report its students who satisfactorily com duty while teaching full-time. findings to a mid-October meeting plete the requirements of the The 1970 R.O.T.C. report of the Executive Council. respective programs" provided which led to revocation of credit Krogh appointed Professors that there are academic courses prohibited the University from Karski, Herdeck and Wasowski, which meet the following stan granting academic credit to R.O. Betty Krob (SFS'74) and Joseph dards: T.C. courses as long as instructors Farkas (SFS'76) to the sub-com • The courses are open for were serving on active duty while mittee. -

ALI-ABA Course of Study Historic Preservation Law

ALI-ABA Course of Study Historic Preservation Law Cosponsored by the National Trust for Historic Preservation April 26 - 27, 2007 Washington, D.C. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PROGRAM xv FACULTY PARTICIPANTS xvii FACULTY BIOGRAPHIES xix STUDY MATERIAL VOLUME 1 OVERVIEW MATERIALS 1. A Layperson's Guide to Historic Preservation Law: A Survey of Federal, 1 State, and Local Laws Governing Historic Resource Protection (PRESERVATION BOOKS, 2005) By Julia H. Miller 2. Glossary of Terms (NTHP PRESERVATION LAW REPORTER EDUCATIONAL 57 MATERIALS, 2007) FEDERAL PRESERVATION LAW 3. Principal Federal Historic Preservation Laws at a Glance 65 By Elizabeth Sherrill Merritt 4. National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (as amended 1980, 1992, 2000, 16 69 U.S.C. §§ 470-470x-6) 5. National Historic Preservation Act Regulations: Protection of Historic 103 Properties, 36 CFR Part 800 (As amended, 2004) 6. Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act and Section 4(f) of the 121 Department of Transportation Act By Elizabeth Sherrill Merritt 7. Protecting Historic Properties: A Citizen's Guide to Section 106 Review and 129 Section 106 Flow Chart with Explanatory Material (Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, 2001) Citizen's Guide 131 Section 106 Regulations Flow Chart and Explanation 143 8. National Environmental Policy Act, (Selected Provisions) (42 U.S.C. §§ 153 4321-4347) vii 9. Federal Highway Administration Materials 159 Submitted by Diane Mobley Section 4(f), as Amended by SAFETEA-LU 161 Department of Transportation Regulations Implementing Section 4(f) (49 U.S.C. § 303, 23 CFR § 771.135) 163 New Statute of Limitations Established by SAFETEA-LU 170 Guidance for Determining De Minimis Impacts to Section 4(f) Resources (Cover Memorandum, Dec. -

NPS Form 10-900 (Rev

NPS Form 10-900 (Rev. 11-90) OMB No. 10024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties or districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to compete all items. 1. Name of Property Historic name: KEYSTONE APARTMENT BUILDING ______ Other names/site number: H.B. BURNS MEMORIAL BUILDING ______ 2. Location Street & Number: 2150 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. [ ] Not for Publication City or town: Washington [ ] Vicinity State: D.C. Code: 001 County Code: Zip Code: 20037 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [ ] nomination [ ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [ ] meets [ ] does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant [ ] nationally [ ] statewide [ ] locally. -

2TI994 National Register of Historic Places ?OWAL Multiple Property Documentation Form Fiegister

NFS Form 10-900-b OMB No 1024-0018 (Revised March 1992) '5 fp n? rj n/7 r? United States Department of the Interior -"« v-lJ is i i W National Park Service 2TI994 National Register of Historic Places ?OWAL Multiple Property Documentation Form fiEGiSTER This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-9000-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. X New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Apartment Buildings in Washington, D.C 1880-1945 B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Apartment Buildings (1880-1945) m Working Class Housing, Alley Dwellings, and Public Housing (1865-1950) C. Form Prepared bv _____ ______________________ name/title Emily Hotaling Big and Laura Harris Hughes Architectural Historians organization Traceries date July, 1993 street & number 5420 Western Avenue_______ telephone (301)656-5283 city or town Chew Chase_____ state Maryland zip code 20815____ D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission" meets the procedural and professional requirements setiorth m 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standard^ and Guidelines for /y^neoljdcv and/HistWa^res^btion. -

GEORGETOWN LAW Res Ipsa Loquitur Fall/Winter 2015

GEORGETOWN LAW Res Ipsa Loquitur Fall/Winter 2015 EXPERIMENT ON K STREET Millions of Americans Can’t Afford a Lawyer The D.C. Affordable Law Firm Plans to Change That Letter from the Dean lmost 50 years ago, Georgetown University Law ACenter put law school clinics on the map. We have continued to be a leader in clinical education ever since. In the last decade we have been at the forefront of an- other landmark innovation in experiential learning as we have developed more than 30 practicum classes, which combine seminars with field placements and provide students with opportunities they can’t get anywhere else. Between our clinical offerings, our practicum and our other experiential course offerings, we can now GEORGETOWN LAW guarantee our second- and third-year law students an Fall/Winter 2015 experiential course every semester. ANNE CASSIDY Editor Another “first” may not just revolutionize legal education but the legal profession itself. Starting this September, we embarked upon a unique experiment: We are team- ANN W. PARKS Senior Writer ing up with two law firms, DLA Piper and Arent Fox, to create a new law firm that BRENT FUTRELL serves people whose incomes make them ineligible for free legal services but who can’t Director of Design afford the $200 to $300 an hour it costs to hire a lawyer in Washington, D.C. The INES HILDE Senior Designer D.C. Affordable Law Firm (see page 24) consists of six of our newly minted graduates trained to provide low bono legal services in the areas of elder law, domestic relations, EMILY ELLER Communications Associate housing, immigration and nonprofit transactional law. -

Ward 3 Heritage Guide

WARD 3 HERITAGE GUIDE A Discussion of Ward 3 Cultural and Heritage Resources District of Columbia Office of Planning Ward 3 Heritage Guide Produced by the DC Historic Preservation Office Published 2020 Unless stated otherwise, photographs and images are from the DC Office of Planning collection. This project has been funded in part by U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service Historic Preservation Fund grant funds, administered by the District of Columbia’s Historic Preservation Office. The contents and opinions contained in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of the Interior, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the U.S. Department of the Interior. This program has received Federal financial assistance for the identification, protection, and/or rehabilitation of historic properties and cultural resources in the District of Columbia. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or disability in its Federally assisted programs. If you believe that you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20240. Next page: View looking Southeast along Conduit Road (today’s MacArthur Boulevard), ca. 1890, Washington Aqueduct TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................. 1 Ward 3 Overview........................................................................ -

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service 1

NPS Form 10-900 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM INTERAGENCY RESOURCES DIVISION This form is for use in nominating or requesting individual properties and districts. See instructions in" itional Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Alban Towers Apartment Building other names/site number 2. Location street & number 3700 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. not for publication N/A city or town Washington________________ ________ vicinity X state District of Columbia code DC zip code 20016 county N/A code N/A 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___X nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant __ nationally X statewide locally. -

Past DC Preservation Award Recipients 2003

Past Recipients District of Columbia Awards for Excellence in Historic Preservation ______ 2003 Preservation Week Awards: Excellence in Preserving History – Shaw Heritage Trust Excellence in Preserving a Residential Property – 1901 Vermont Avenue, NW Excellence in Preserving a Commercial Property – True Reformer Building Fall Awards Program: Individual Lifetime Achievement – Teresa Brown Excellence in Stewardship – The Historical Society of Washington, DC and The City Museum Excellence in Community Involvement – Ivy City-Trinidad Citizens Association for the Alexander Crummell School The Rosedale Conservancy Avalon Theatre Excellence in Heritage Education – Bloomingdale Boys Club The Ruth Ann Overbeck Capitol Hill History Project Excellence in Communications – Elizabeth Weiner, Northwest Current Excellence in Design – Old General Post Office/Hotel Monaco The Gallup Building 1209 O Street, NW Excellence in Public Archaeology – Sidwell Friends School Archaeology Project State Historic Preservation Officer’s Award for Preservation Leadership – Capitol Hill Restoration Society HPRB Chairman’s Award for Law and Public Policy – DC Councilmember Sharon Ambrose DC Historic Preservation 25th Anniversary Award – Don’t Tear It Down/DC Preservation League 2004 Individual Lifetime Achievement – Charles Atherton Excellence in Stewardship – Heurich House Foundation Adas Israel Synagogue Excellence in Community Involvement – Washington Convention Center Authority Historic Preservation Fund 1132 Park Street, NE Façade Restoration Excellence in Heritage -

DISTRICT of COLUMBIA INVENTORY of HISTORIC SITES ALPHABETICAL VERSION September 30, 2009

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES ALPHABETICAL VERSION September 30, 2009 The District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites is the District government’s list of officially designated historic properties. Properties in the Inventory are deemed worthy of recognition and protection for their contribution to the cultural heritage of one of the nation’s most beautiful and historic cities. 2009 Inventory The D.C. Inventory originated in 1964, with 289 listings. The 2009 version of the Inventory contains more than 700 designations encompassing nearly 25,000 properties. Included in the Inventory are: 500 historic landmark designations covering more than 800 buildings 150 historic landmark designations of other structures, including parks, engineering structures, monuments, building interiors, artifacts, and archaeological sites 50 historic districts, including 28 neighborhood historic districts. Properties in the Inventory properties are protected by both local and federal historic preservation laws. The D.C. Historic Preservation Review Board (HPRB) designates properties for inclusion in the Inventory, and the D.C. Historic Preservation Office (HPO) maintains the Inventory and supporting documentation. A component of the D.C. Office of Planning, HPO is both the staff to the Review Board and the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) for the District of Columbia. Searching the Inventory The 2009 version of the D.C. Inventory is presented in multiple formats for convenience. Each of these formats is available on the HPO website and may be obtained in an electronic copy. The main or thematic version of the Inventory is arranged to promote understanding of significant properties within their historic context. Designations are grouped by historical period and theme (see the Table of Contents). -

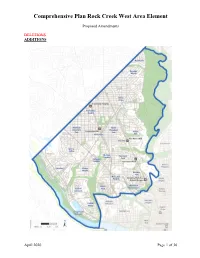

Rock Creek West Element

Comprehensive Plan Rock Creek West Area Element Proposed Amendments DELETIONS ADDITIONS April 2020 Page 1 of 36 Comprehensive Plan Rock Creek West Area Element Proposed Amendments 2300 OVERVIEW Overview 2300 2300.1 The Rock Creek West Planning Area encompasses 13 square miles in the northwest quadrant of the District of Columbia Washington, DC. The Planning Area is bounded by Rock Creek onto the east, Maryland on to the north/west, and the Potomac River and Whitehaven Parkway on to the south. Its boundaries are shown in the Map map at left. Most of this area has historically been Ward 3, although but in past and present times, some parts have been included in WwardsWards 1, 2, and 4. 2300.1 2300.2 Rock Creek West’s most outstanding characteristic is its stable high-opportunity, attractive neighborhoods. These include predominantly single-family neighborhoods, such as like Spring Valley, Forest Hills, American University Park, and Palisades; row house and garden apartment neighborhoods like Glover Park and McLean Gardens; and mixed-density neighborhoods such as Woodley Park, Chevy Chase, and Cleveland Park. Although these communities retain individual and distinctive identities, they share a commitment to proactively addressing land use and development issues and conserving neighborhood quality. 2300.2 2300.3 Some of Washington, DC’s the District’s most important natural and cultural resources are located in Rock Creek West. These resources include Rock Creek Park, the National Zoo, Glover Archbold Park, Battery Kemble Park, and Fort Reno Park, as well as numerous smaller parks and playgrounds. Many of these areas serve as resources for the entire city. -

The Foreign Service Journal, June 1958

Before you buy any Canadian whisky turn the bottle "ABOUT FACE!' Only O.F.C. bears this certificate...your guarantee that every drop is over 6 years old! Unlike other leading Canadian whiskies, which show no minimum age, and may vary their SIX YEARS OLD age from 3 to 6 years old, O.F.C. is always over IMPORTED six years old. And only O.F.C. lets you know FROM CANADA its exact age by placing this “Certificate of Age” on every bottle you buy. Thus you can rest assured that every drop of O.F.C. has the same world-famous taste and quality, never changing, never excelled. Yet O.F.C. costs no O.F.C. more than other Canadians. Buy O.F.C. Canadian ^Schenky with the guarantee! SCHENLEY INTERNATIONAL CORP. • NEW YORK, N.Y. The ?ire$tone NYLON “500” Protects Against Impact The Firestone Nylon Safety-Tensioned Gum- Dipped Cord body is 91 % stronger, making it vir¬ tually immune to impact danger. Protects Against Punctures and Blowouts A special air-tight safety liner seals against punc¬ turing objects and makes blowouts as harmless as a slow leak. Protects Against Skidding The Gear Grip Safety Tread with thousands of safety angles provides a Safety Proved on silent ride and greater the Speedway for Your traction under all driving conditions. Protection on the Highway FIRESTONE INTERNATIONAL AND INTERAMERICA COMPANY FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL 1 World’s Most Magnificent Radio ALL-TRANSISTOR (Tubeless) TRANS-OCEANIC® Smallest and lightest standard and band-spread short wave portable ever produced! 10%" high; 12%" wide; 4%"deep.