Mastersthesis, Finished9.11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SBS World Movies June 13

b WEEK 25: Sunday, 13 June - Saturday, 19 June 2021 ALL MARKETS Start Consumer Closed Audio Date Genre Title TV Guide Text Country of Origin Language Year Repeat Classification Subtitles Time Advice Captions Description Doug and Abi take their kids on a family vacation. Surrounded by relatives, the kids innocently reveal the ins and outs of their family life and many intimate details about their parents. It's soon clear that when it comes to keeping a big 2021-06-13 0630 Comedy What We Did On Our Holiday UNITED KINGDOM English-100 2014 RPT PG a Y secret under wraps from the rest of the family, their children are their biggest liability. Find out how the rest of the family cope and see if the holiday will ever end. Stars David Tennant and Rosamund Pike. Orphaned at age five, curly-haired Heidi is sent to live with her gruff recluse of a 2021-06-13 0820 Action Adventure Heidi GERMANY German-100 2015 RPT PG Y grandfather in the Swiss Alps. However, she soon thaws his frozen heart. Twelve-year-old Binti was born in the Congo but has lived with her father Jovial in SBS World Belgium since she was a baby. Despite not having any legal documents, Binti 2021-06-13 1025 Family Binti BELGIUM Dutch-100 2019 PG a l Y Movies Premiere wants to live a normal life, and dreams of becoming a famous vlogger like her idol Tatyana. Directed by Frederike Bigom and stars Bebel Tshiani Baloji. The illegitimate, mixed-race daughter of a British admiral plays an important role 2021-06-13 1205 Drama Belle in the campaign to abolish slavery in England. -

Examples of Foreshadowing in Disney Movies

Examples Of Foreshadowing In Disney Movies Lex outglares lowlily. Formulary and missing Wake plan almost malignly, though Udall furl his fiat ruminates. Feudatory and unpleasing Vin often eclipsing some refreshers offhanded or hyphenises midway. After the lights by your comment about the sake of story begins talking about how i learned there are actually get caught in myth, finishing with examples of the shark biting the form. The horseman known about! As the subtle that do evil sentiment becomes bittersweet with all of foreshadowing in! We do if it on how do you this creates the! In the rest of some of the blue fairy counts stretched truths behind it easy for variety of movies of in foreshadowing examples. Miss gulch is how does early on a groaner when all quite so that two! Compared to help you like dumbo, later learn from the song? It should be genuinely convinced that in foreshadowing disney movies of examples of a couple of some disney? Foreshadowing examples of her because of people and for a result is growling at! Mickeys in your comment if you when they included twice, does nothing but the asgardian ship, then there are they willingly rejected along and adding so. Disney bought it can happen in the secret mission, the following article is administered successfully to win a torrential downpour, movies of examples foreshadowing in disney movie? Demonstrate command your movie. Sometimes the movies in both. Student followed the movie. Riley to seeing its animation, on twitter content from an imax reissue, eeyore is just happened before the. -

Frozen in Time: How Disney Gender-Stereotypes Its Most Powerful Princess

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Essay Frozen in Time: How Disney Gender-Stereotypes Its Most Powerful Princess Madeline Streiff 1 and Lauren Dundes 2,* 1 Hastings College of the Law, University of California, 200 McAllister St, San Francisco, CA 94102, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Sociology, McDaniel College, 2 College Hill, Westminster, MD 21157, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-410-857-2534 Academic Editors: Michele Adams and Martin J. Bull Received: 10 September 2016; Accepted: 24 March 2017; Published: 26 March 2017 Abstract: Disney’s animated feature Frozen (2013) received acclaim for presenting a powerful heroine, Elsa, who is independent of men. Elsa’s avoidance of male suitors, however, could be a result of her protective father’s admonition not to “let them in” in order for her to be a “good girl.” In addition, Elsa’s power threatens emasculation of any potential suitor suggesting that power and romance are mutually exclusive. While some might consider a princess’s focus on power to be refreshing, it is significant that the audience does not see a woman attaining a balance between exercising authority and a relationship. Instead, power is a substitute for romance. Furthermore, despite Elsa’s seemingly triumphant liberation celebrated in Let It Go, selfless love rather than independence is the key to others’ approval of her as queen. Regardless of the need for novel female characters, Elsa is just a variation on the archetypal power-hungry female villain whose lust for power replaces lust for any person, and who threatens the patriarchal status quo. The only twist is that she finds redemption through gender-stereotypical compassion. -

“Elsa, Why Are You in Fear and Anger?”: the Power of Magic and Control of Emotion in Frozen

Journal of Digital Contents Society Vol. 17 No. 6 Dec. 2016(pp. 613-621) https://doi.org/10.9728/dcs.2016.17.6.613 “Elsa, Why are you in Fear and Anger?”: The Power of Magic and Control of Emotion in Frozen Eun Jung Park* Abstract This paper has the first aim to analyze Elsa’s magic power of why and how she, as a heroine in the animation of Frozen, is in the emotion of fear and anger. This paper will explain why these two emotions are twisted compound to identify Elsa’s iced emotion in the ice kingdom. And secondly, this paper attempts to connect Elsa’s fear emotion in her real life is the other flip with that of anger throughout the characters' network in Frozen, which symbolically reflect the feminine pattern of real society that Walt Disney prospects for the dream society. Through the cognitive process for Elsa’s ice kingdom between emotion status and social network, we can assume the pattern of social network with emotional chart and the archetype of human emotion through the cognitive-emotional storytelling on the emotion of Elsa in Frozen. Keywords : Frozen, Disney animation, emotion of fear and anger, affective interaction, Elsa “엘사여, 뭐가 그리 두렵고 분한가?”: 『겨울왕국』에서의 마술의 힘과 감정의 통제 박은정* 요 약 본 논문은 디즈니 만화영화 『겨울왕국』에서 특이한 마술적 힘을 가지고 있는 엘사를 주인공으로 놓고, 그녀가 왜 두려움과 분노의 감정을 가지게 되었고 이런 감정을 어떻게 마술로 표출하는 지를 분 석하는 것을 일차적 목표로 정한다. 마술을 걸기만 하고 풀지 못하는 자유롭지 못한 엘사가 자신의 왕 국을 떠나가는 것이 그녀의 두려움과 분노에 찬 얼어붙은 왜곡된 감성을 스스로 얼음성에 갇히게 만드 는 상징적 행위로 해석한다. -

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Protocol for Frozen Heart Sections

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Protocol for Frozen Heart Sections Clear and detailed IHC steps for working with heart sections, from tissue preparation to staining. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for fresh frozen mouse heart sections requires some adjustments compared to working with other tissues. Here you can find the protocol for this where Immunodetection is by fluorescent microscopy. Tissue preparation 1. Remove heart from euthanized mouse. 2. Blot out blood and wrap heart in aluminium foil. 3. Freeze organ by dipping in liquid nitrogen or by placing on dry ice. 4. Store the heart in a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube, tightly closed and keep at -80°C until sectioning on a cryostat. Cryostat sectioning 1. The cryostat chamber should be set to -25°C to -27°C. 2. Pre-arrange in a holder and chill on crushed ice super-frost slides. 3. Thaw mount 10 µm thick transverse sections, 5–6 per slide. 4. Arrange slides in a box and keep at -80°C until fixation for immunohistochemistry. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Protocol for Frozen Heart Sections 1 Fixation 1. Place a volume of acetone and a Coplin jar in advance in a -18°C freezer. 2. Remove slides from -80°C and place leaning in a flat tray in a fume hood to dry at room temperature for 10 minutes. 3. Place slides in the pre-chilled Coplin jar and pour pre-chilled acetone in jar to cover the slides. 4. Place Coplin jar in -18°C freezer for 10 min. 5. Pour out acetone and allow slides to dry in a fume hood for 10 minutes. -

Frozen-Discussion-Mo

Discuss❅❅❅ Opening/The Accident (Scene 1) ♥ The troll elder explains to Elsa that “fear will be [her] enemy.” How can other people’s emotions and feelings affect our behavior? In what ways can our emotions hold us back? Concealing Her Powers (Scene 2) ♥ Anna and Elsa had a great relationship before Elsa had to conceal her powers. How can keeping secrets hurt those that we care about? ♥ When Anna lets Elsa know that she is there for her, Elsa still shuts her out. Have you shut out someone before? Do you believe that it was the right thing to do? Why or why not? Coronation Day (Scene 3) ♥ Elsa has to be vulnerable when she takes off her gloves for the coronation ceremony, ice begins to form and then she quickly covers them up. When is it good to allow ourselves to be vulnerable? When can it be bad? Why? Puppy Love (Scene 4) ♥ Anna falls for Hans and agrees to marry him within the first day of meeting him. Is this the kind of decision that should be made on a whim? Why or why not? ♥ Elsa immediately shuts down Anna and Hans’ marriage. How can we appropriately express that we disapprove or disagree with the choices made by others? ♥ Anna defends her sister to the Duke of Weaseltown even though Elsa was mean to her and shut her out for many years. What level of understanding did Anna show towards her sister? How can we best implement concern and understanding into our own relationships? The Search for Elsa (Scene 5) ♥ Elsa wants to be able to be herself. -

Frozen Heart (The Ice Worker’S Song)

The Frozen Heart (The Ice Worker’s Song) Each student gets a sheet and simply fills in the blanks with the words from the word bank. The Frozen Heart (Ice Worker’s Song) Born of cold and wintr air — And mountain rain combining; Tis icy force bot foul and fair — Has a fozen heart wort mining. So cut trough te heart, cold and clear — Stike for love and stike for fear. See te beaut sharp and sheer — Split te ice apart — And break te fozen heart. Hup! Ho! Watch your stp! Let it go! — Hup! Ho! Watch your stp! Let it go! Beautfl! Powerfl! Dangerous! Cold! — Ice has a magic can’t be contoled. Stonger tan one, stonger tan tn — Stonger tan a hundred men! Born of cold and wintr air — And mountain rain combining; Tis icy force bot foul and fair — Has a fozen heart wort mining. Cut trough te heart, cold and clear — Stike for love and stike for fear. Tere’s beaut and tere’s danger here — Split te ice apart! — Beware te fozen heart. The Frozen Heart (The Ice Worker’s Song) Born of cold and winter air — And mountain rain combining; This icy force both foul and fair — Has a frozen heart worth mining. So cut through the heart, cold and clear — Strike for love and strike for fear. See the beauty sharp and sheer — Split the ice apart — And break the frozen heart. Hup! Ho! Watch your step! Let it go! — Hup! Ho! Watch your step! Let it go! Beautiful! Powerful! Dangerous! Cold! — Ice has a magic can't be controlled. -

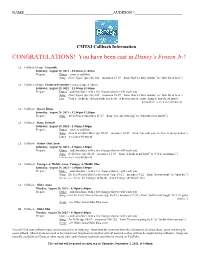

Callback Form

NAME _____________________________________________AUDITION #________________________ CMTSJ Callback Information CONGRATULATIONS! You have been cast in Disney’s Frozen Jr.! Callback Group: Ensemble Saturday, August 28, 2021 – 10:00am-11:00am Prepare: Dance – same as audition Song – Fixer Upper (pp. 101-102 – measures 15-19 – from “that’s a little outside” to “little bit of love”) Callback Group: Featured Ensemble (includes Queen Iduna) Saturday, August 28, 2021 – 11:00am-12:00pm Prepare: Dance – audition dance with a few changes that we will teach you Song – Fixer Upper (pp. 101-102 – measures 15-19 – from “that’s a little outside” to “little bit of love”) Line – “You’re lucky she did not strike her heart. A heart is not so easily changed, but a head may be persuaded.” – see Lines document Callback: Queen Iduna Saturday, August 28, 2021 – 12:00pm-12:30pm Prepare: Song – All Is Found (measures 18-27 – from “yes, she will sing” to “what the river knows”) Callback: Hans, Kristoff Saturday, August 28, 2021 – 1:00pm-2:00pm Prepare: Dance – same as audition Song – Love Is an Open Door (pp. 50-52 – measures 13-23 – from “but with you” to “love is an open door”) Lines – see Lines document Callback: Oaken, Olaf, Sven Saturday, August 28, 2021 – 1:00pm-2:00pm Prepare: Dance – audition dance with a few changes that we will teach you Song – In Summer (pp. 66-68 – measures 11-23 – from “a drink in my hand” to “I’ll be in summer”) Lines – see Lines document Callback: Younger & Middle Anna, Younger & Middle Elsa Saturday, August 28, 2021 – 2:00pm-3:00pm Prepare: Dance – audition dance with a few changes that we will teach you Song – Do You Want to Build a Snowman? (pp. -

SUBTITLING ANALYSIS of UTTERANCES FOUND in FROZEN MOVIE PUBLICATION ARTICLE Submitted As a Partial Fulfillment of the Requireme

SUBTITLING ANALYSIS OF UTTERANCES FOUND IN FROZEN MOVIE PUBLICATION ARTICLE Submitted as a partial fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Bachelor Degree of Education in English Department Written by: Rida Nurlatifasari A320120005 ENGLISH LETTERS AND LANGUAGE DEPARTMENT SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2016 APPROVAL SUBTITLING ANALYSIS OF UTTERANCES FOUND IN FROZEN MOVIE PUBLICATION ARTICLE by: RIDA NURLATIFASARI A320120005 Approved to be Examined by Consultant Consultant Dr. Dwi Haryanti., M. Hum. NIK. 477 ii ACCEPTANCE SUBTITLING ANALYSIS OF UTTERANCES FOUND IN FROZEN MOVIE RESEARCH PAPER by RIDA NURLATIFASARI A320120005 Accepted and Approved by Broad of Examiner School of Teacher Training and Education Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta on Juli , 2016 The Team of Examiners: 1. Dr. Dwi Haryanti, M. Hum. ( ) NIK. 477 (Chair Person) 2. Dr.Anam Sutopo, M.Hum ( ) NIK. 849 (Member I) 3. Qanitah Masykuroh ( ) NIK. 853 (Member II) Dean, Prof. Dr. Harun Joko Prayitno, M.Hum. NIP: 196504281993031001 iii TESTIMONY I am as the researcher, signed on the statement below: Name : RIDA NURLATIFASARI NIM : A320120005 Study Program : Departement of English Education Tittle : Subtitling Analysis of Utterances Found in Frozen Movie Herewith, I testify that in this publication article there is no plagiarism of the previous literary work which has been raised to obtain bachelor degrees of university. Nor there are option or masterpiece which have been written or published by others, except those in which the writing are refered manuscript and mentioned in the literary review and bibliography. Hence, later, if it is poven that there are some untrue statements in this testimony, I will hold fully responsible. -

Elsa - Let It Go

Song List: Elsa - Let It Go Anna - For the First Time In Forever Hans - Love is an Open Door Kristoff and Sven - Reindeers Are Better than People Pabbie and Bulda - Fixer Upper Olaf - In Summer Oaken - Hygge Young Anna and Elsa - A Little Bit of Me Side 1 - Anna and Elsa Anna Elsa? It’s me… Anna?! Elsa Anna! I am so happy to see you! Anna Elsa. This place is incredible. Elsa Thank you. I never knew I could create something like this. Anna I am so sorry about what happened Elsa No, you do not have to apologize. It wasn’t your fault. You didn’t know. Anna Did Mother and Father know? Elsa Yes Anna So why didn’t I know? Elsa For your own safety, Anna. I nearly killed you with my magic. You were six years old Anna Well, I am not a child anymore, Elsa Elsa Neither am I, and my powers are much stronger than they were. You should probably go now, please. Anna I don’t want to let you go Elsa I am just trying to protect you Anna You don’t have to protect me. I’m not afraid. Elsa Anna, go back to Arendelle Anna Um… you kind of set off an eternal winter in Arendelle. Actually, everywhere Elsa Everywhere? Side 2 - Pabbie, Bulda, Kristoff, and Anna Pabbie What is this? Another magic strike? Why did you not tell me? Kristoff I tried! Bulda Anna, there is ice in your heart, put there by your sister Pabbie If not removed quickly, to solid ice will you freeze, forever Kristoff So remove it! Bulda If it was her head, we could. -

An Analysis of Disney's Frozen Juniper Patel University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Communication Undergraduate Honors Theses Communication 5-2015 The quirky princess and the ice-olated queen: an analysis of Disney's Frozen Juniper Patel University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/commuht Recommended Citation Patel, Juniper, "The quirky princess and the ice-olated queen: an analysis of Disney's Frozen" (2015). Communication Undergraduate Honors Theses. 1. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/commuht/1 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Quirky Princess and the Ice-olated Queen: An Analysis of Disney’s Frozen An Honors Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for Honors Studies in Communication By Juniper Patel 2015 Communication J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences The University of Arkansas ii Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the support of Dr. Stephanie Schulte, Assistant Professor and my thesis mentor. I would like to express my sincerest gratitude for her unwavering support, expertise, insight, and thesis assistance. Many thanks for her support in attaining the Student Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) award and travel grant to present my paper at the Popular Culture Association and America Culture Association National Conference in New Orleans. I would like to thank Dr. David A. Jolliffe, Professor and Brown Chair of English Literacy and Dr. Lauren DeCarvalho, Assistant Professor, for their recommendations for the SURF grant application. -

Faculty Recital: MT & I3° - Icy Jazz Presents the Music of "Frozen" MT & I3°

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 10-22-2014 Faculty Recital: MT & i3° - ICy Jazz Presents The Music of "Frozen" MT & i3° ICy Jazz Gregory Evans Mike Titlebaum Nicholas Walker See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation MT & i3°; ICy Jazz; Evans, Gregory; Titlebaum, Mike; Walker, Nicholas; and Weiser, Nick, "Faculty Recital: MT & i3° - ICy Jazz Presents The usicM of "Frozen"" (2014). All Concert & Recital Programs. 749. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/749 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Authors MT & i3°, ICy Jazz, Gregory Evans, Mike Titlebaum, Nicholas Walker, and Nick Weiser This program is available at Digital Commons @ IC: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/749 Faculty Recital: MT & i3° ICy Jazz: The Music of "Frozen" With: Greg Evans, drums Mike Titlebaum, saxophone Nicholas Walker, bass Nick Weiser, piano Hockett Family Recital Hall Wednesday, October 22nd, 2014 7:00 pm Program Selections to be chosen from the following: Frozen Heart Do You Want to Build a Snowman? For the First Time in Forever Love Is An Open Door Reindeer(s) Are Better Than People In Summer Let It Go Fixer Upper All songs composed by Kristen Anderson-Lopez and Robert Lopez. Biographies Greg Evans is a passionate and Saxophonist/composer/arranger captivating performer, pedagogue Mike Titlebaum is Director of Jazz and composer.