Nova Scotia's First Tele Graph System Thomas H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the Atlantic Provinces ' Published by Parks Canada Under Authority Ot the Hon

Parks Pares Canada Canada Atlantic Guide to the Atlantic Provinces ' Published by Parks Canada under authority ot the Hon. J. Hugh Faulkner Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs, Ottawa, 1978. QS-7055-000-EE-A1 Catalogue No. R62-101/1978 ISBN 0-662-01630-0 Illustration credits: Drawings of national historic parks and sites by C. W. Kettlewell. Photo credits: Photos by Ted Grant except photo on page 21 by J. Foley. Design: Judith Gregory, Design Partnership. Cette publication est aussi disponible en français. Cover: Cape Breton Highlands National Park Introduction Visitors to Canada's Atlantic provinces will find a warm welcome in one of the most beautiful and interesting parts of our country. This guide describes briefly each of the seven national parks, 19 national historic parks and sites and the St. Peters Canal, all of which are operated by Parks Canada for the education, benefit and enjoyment of all Canadians. The Parliament of Canada has set aside these places to be preserved for 3 all time as reminders of the great beauty of our land and the achievements of its founders. More detailed information on any of the parks or sites described in this guide may be obtained by writing to: Director Parks Canada Atlantic Region Historic Properties Upper Water Street Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J1S9 Port Royal Habitation National Historic Park National Parks and National Historic 1 St. Andrews Blockhouse 19 Fort Amherst Parks and Sites in the Atlantic 2 Carleton Martello Tower 20 Province House Provinces: 3 Fundy National Park 21 Prince Edward Island National Park 4 Fort Beausejour 22 Gros Morne National Park 5 Kouchibouguac National Park 23 Port au Choix 6 Fort Edward 24 L'Anse aux Meadows 7 Grand Pré 25 Terra Nova National Park 8 Fort Anne 26 Signal Hill 9 Port Royal 27 Cape Spear Lighthouse 10 Kejimkujik National Park 28 Castle Hill 11 Historic Properties 12 Halifax Citadel 4 13 Prince of Wales Martello Tower 14 York Redoubt 15 Fortress of Louisbourg 16 Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Park 17 St. -

Closure of Important Parks Canada Archaeological Facility The

July 19, 2017 For Immediate Release Re: Closure of Important Parks Canada Archaeological Facility The Newfoundland and Labrador Archaeological Society is saddened to learn of Parks Canada’s continuing plans to close their Archaeology Lab in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. This purpose-built facility was just opened in 2009, specifically designed to preserve, house, and protect the archaeological artifacts from Atlantic Canada’s archaeological sites under federal jurisdiction. According to a report from the Nova Scotia Archaeological Society (NSAS), Parks Canada’s continued plans are to shutter this world-class laboratory, and ship the archaeological artifacts stored there to Gatineau, Quebec, for long-term storage. According to data released by the NSAS, the archaeological collection numbers approximately “1.45 million archaeological objects representing thousands of years of Atlantic Canadian heritage”. These include artifacts from the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, including sites at Signal Hill National Historic Site, Castle Hill National Historic Site, L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site, Terra Nova National Park, Gros Morne National Park, and the Torngat Mountains National Park. An archaeological collection represents more than just objects—also stored at this facility are the accompanying catalogues, site records, maps and photographs. For Immediate Release Re: Closure of Important Parks Canada Archaeological Facility This facility is used by a wide swath of heritage professionals and students. Federal and provincial heritage specialists, private heritage industry consultants, university researchers, conservators, community groups, and students of all ages have visited and made use of the centre. Indeed, the Archaeology Laboratory is more than just a state-of-the-art artifact storage facility for archaeological artifacts—its value also lies in the modern equipment housed in its laboratories, in the information held in its reference collections, site records, and book collections, and in the collective knowledge of its staff. -

3.6Mb PDF File

Be sure to visit all the National Parks and National Historic Sites of Canada in Nova Scotia: • Halifax Citadel National • Historic Site of Canada Prince of Wales Tower National • Historic Site of Canada York Redoubt National Historic • Site of Canada Fort McNab National Historic • Site of Canada Georges Island National • Historic Site of Canada Grand-Pré National Historic • Site of Canada Fort Edward National • Historic Site of Canada New England Planters Exhibit • • Port-Royal National Historic Kejimkujik National Park of Canada – Seaside • Site of Canada • Fort The Bank Fishery/Age of Sail Exhibit • Historic Site of Canada • Melanson SettlementAnne National Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site National Historic Site of Canada • of Canada • Kejimkujik National Park and Marconi National Historic National Historic Site of Canada • Site of Canada Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site of • Canada Canso Islands National • Historic Site of Canada St. Peters Canal National • Historic Site of Canada Cape Breton Highlands National Park/Cabot T National Parks and National Historic rail Sites of Canada in Nova Scotia See inside for details on great things to see and do year-round in Nova Scotia including camping, hiking, interpretation activities and more! Proudly Bringing You Canada At Its Best Planning Your Visit to the National Parks and Land and culture are woven into the tapestry of Canada's history National Historic Sites of Canada and the Canadian spirit. The richness of our great country is To receive FREE trip-planning information on the celebrated in a network of protected places that allow us to National Parks and National Historic Sites of Canada understand the land, people and events that shaped Canada. -

FORT ANNE National Historic Site

FORT ANNE National Historic Site 1 S A L 2 L S Y E 3 P C V 4 O H C E 5 6 P O W D E R M A G A Z I N E C T R N U 7 8 9 M A T O R B 10 I C Q U E E N A N N E T L 11 K T A R A A 12 13 M A D A D I C 14 15 16 C H A M P L I A N L O Y A L I S T N K 17 Q E A N K R C W H 18 19 S R A V E L I N D E P O R T A T I O N T P N A L L L 20 21 22 23 M O R T A R P O C G P O R T R O Y A L E Y L L H Y N 24 H A L I F A X I N S R S 25 26 M U S K E T G L A C I S T E E 27 R B A S T I O N S F 28 F O R T A N N E R 29 T H I R T E E N Across 25. Infantryman’s gun with long barrel 7. The first nation who occupied the 5. The oldest building in Parks Canada (2 26. Slope of land shaped so all areas are territory for over 3,000 years words) covered by canon and musket fire 8. -

ACTION STATIONS! Volume 37 - Issue 1 Winter 2018

HMCS SACKVILLE - CANADA’S NAVAL MEMORIAL ACTION STATIONS! Volume 37 - Issue 1 Winter 2018 Action Stations Winter 2018 1 Volume 37 - Issue 1 ACTION STATIONS! Winter 2018 Editor and design: Our Cover LCdr ret’d Pat Jessup, RCN Chair - Commemorations, CNMT [email protected] Editorial Committee LS ret’d Steve Rowland, RCN Cdr ret’d Len Canfield, RCN - Public Affairs LCdr ret’d Doug Thomas, RCN - Exec. Director Debbie Findlay - Financial Officer Editorial Associates Major ret’d Peter Holmes, RCAF Tanya Cowbrough Carl Anderson CPO Dean Boettger, RCN webmaster: Steve Rowland Permanently moored in the Thames close to London Bridge, HMS Belfast was commissioned into the Royal Photographers Navy in August 1939. In late 1942 she was assigned for duty in the North Atlantic where she played a key role Lt(N) ret’d Ian Urquhart, RCN in the battle of North Cape, which ended in the sinking Cdr ret’d Bill Gard, RCN of the German battle cruiser Scharnhorst. In June 1944 Doug Struthers HMS Belfast led the naval bombardment off Normandy in Cdr ret’d Heather Armstrong, RCN support of the Allied landings of D-Day. She last fired her guns in anger during the Korean War, when she earned the name “that straight-shooting ship”. HMS Belfast is Garry Weir now part of the Imperial War Museum and along with http://www.forposterityssake.ca/ HMCS Sackville, a member of the Historical Naval Ships Association. HMS Belfast turns 80 in 2018 and is open Roger Litwiller: daily to visitors. http://www.rogerlitwiller.com/ HMS Belfast photograph courtesy of the Imperial -

(MEDC) AGENDA September 12, 2017 at 6:00 Pm Members: Chai

Town of Annapolis Royal Marketing and Economic Development Committee September 12, 2017 Town of Annapolis Royal Marketing and Economic Development Committee (MEDC) AGENDA September 12, 2017 at 6:00 pm Members: Chair Councillor Owen Elliot, Vice-Chair Amy Barr, Councillor Holly Sanford, Mayor MacDonald, Diana Lewis, Samantha Myhre and Benjamin Boysen. Administration: CAO Greg Barr and Recording Secretary Sandi Millett-Campbell. 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 3. APPROVAL OF THE MINUTES – July 11, 2017 (Tab 1) 4. PUBLIC INPUT 5. PRESENTATIONS i. Twinning Committee Update – Christine Igot (Tab 2) 6. BUSINESS ARISING i. Workplan – Population Strategies (Tab 3) ii. Natal Day Wrap Up – Councillor Sanford iii. Tall Ships Wrap Up – Sandi Millett-Campbell iv. Community Identity Signage v. Town Crier Expanded Distribution 7. NEW BUSINESS i. Ghost Town ii. Doers & Dreams 2018 (Tab 4) iii. MEDC/ABoT Fall Luncheon – Proposed date October 11, 2017 8. TWINNING COMMITTEE MINUTES – (Tab 5) 9. CORRESPONDENCE FOR INFORMATION 10. ADJOURNMENT 11. Next Meeting: MEDC – October 10, 2017 at 6:00 pm Town of Annapolis Royal Marketing and Economic Development Committee July 11, 2017 Town of Annapolis Royal Marketing and Economic Development Committee (MEDC) AGENDA July 11, 2017 at 6:00 pm Members: Chair Councillor Owen Elliot, Vice-Chair Amy Barr, Councillor Holly Sanford, Samantha Myhre and Benjamin Boysen. Administration: CAO Greg Barr and Recording Secretary Courtney Campbell. Regrets: Diana Lewis, Mayor Bill MacDonald 1. CALL TO ORDER: Chair Elliot called the meeting to order at 6:02pm. 2. APPROVAL OF AGENDA: MOTION #MEDC-2017-JUL-11-1 It was moved by Councillor Sanford, seconded by Amy Barr, to approve the July 11, 2017 agenda as presented. -

June 2016 Newsletter

DWIGHT ROSS ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PO Box 1420, 949 Tremont Mountain Road Greenwood, Nova Scotia BOP 1NO Telephone: (902) 765-7510 Fax: (902) 765-7520 EMail: [email protected] Website: www.dres.ednet.ns.ca L. J. Hewson, Principal B. Green, Secretary June 2016 Newsletter Dates to Remember Jun 2—School Trips—Oaklawn Farm Zoo & Fort Anne/Port Royal National Historic Sites Jun 3—Last Day for library sign out PTA Spirit Day: Shades Day Early Dismissal—students dismissed at 11:30 am Jun 6—Grade 5 orientation at Pine Ridge Middle School Jun 8—Parent Info Session at PRMS 6:00 pm Jun 10—Last day for library classes—all books must be returned Jun 14—Precision Dance Association presentation (time to be announced) Jun 22—Field Day in the morning June Good News Assembly 1:15 pm Volunteer Social to follow assembly Jun 24 & 27—Marking Days—No School for students Jun 28—Inservice—No school for students Jun 29—Closing Ceremony 9:30 am Last Day of School Early Dismissal—students dismissed at 11:30 am End of Year School Trips On June 2nd, Dwight Ross Elementary students and staff will travel, by bus, to the Oaklawn Farm Zoo in Aylesford and Fort Anne/Port Royal National Historic Sites, in Annapolis Royal and Granville Ferry. P-2 students and staff will be going to the zoo and grade 3-5 students will be going to the Historic Sites. This day will prove to be an educational and fun day for all. Last day for Breakfast & Milk Programs Friday, June 17th will be the last day for our milk and breakfast programs. -

Cultural Assets of Nova Scotia African Nova Scotian Tourism Guide 2 Come Visit the Birthplace of Canada’S Black Community

Cultural Assets of NovA scotiA African Nova scotian tourism Guide 2 Come visit the birthplace of Canada’s Black community. Situated on the east coast of this beautiful country, Nova Scotia is home to approximately 20,000 residents of African descent. Our presence in this province traces back to the 1600s, and we were recorded as being present in the provincial capital during its founding in 1749. Come walk the lands that were settled by African Americans who came to the Maritimes—as enslaved labour for the New England Planters in the 1760s, Black Loyalists between 1782 and 1784, Jamaican Maroons who were exiled from their home lands in 1796, Black refugees of the War of 1812, and Caribbean immigrants to Cape Breton in the 1890s. The descendants of these groups are recognized as the indigenous African Nova Scotian population. We came to this land as enslaved and free persons: labourers, sailors, farmers, merchants, skilled craftspersons, weavers, coopers, basket-makers, and more. We brought with us the remnants of our cultural identities as we put down roots in our new home and over time, we forged the two together and created our own unique cultural identity. Today, some 300 years later, there are festivals and gatherings throughout the year that acknowledge and celebrate the vibrant, rich African Nova Scotian culture. We will always be here, remembering and honouring the past, living in the present, and looking towards the future. 1 table of contents Halifax Metro region 6 SoutH SHore and YarMoutH & acadian SHoreS regionS 20 BaY of fundY & annapoliS ValleY region 29 nortHuMBerland SHore region 40 eaStern SHore region 46 cape Breton iSland region 50 See page 64 for detailed map. -

Adventure Cyclist August 2000

Untroubled Paradise Nova Scotia’s turbulent past has given way to an idyllic present got aboard the Air Nova flight for Halifax with my bike around town on my rented bike with my own gel-cushioned saddle crammed into my carry-on and my helmet dan- saddle installed. The town was lively at night. Teenagers gling from my arm in a plastic grocery bag. Apprehen- roller-bladed along the main street; children played in the sion and anticipation churned in equal parts in my little park across from the inn, with its flower beds and Vic- I torian gazebo; couples strolled along the waterfront, where stomach. Not about the flight, though this small commuter plane looked rather marginal lights and laughter spilled from busy restaurants and Author for flying over the North coffeehouses. Beside the harbor, a circle of granite Dorothy Atlantic to a foreign country. obelisks paid tribute to Lunenburg’s fishermen. Each Stephens had It was the Nova Scotia hills one listed the names of those who had been lost at some rough that I worried about. From sea. The center one bore the names of the ships that times ahead all accounts, they could had gone down. of her as she tests and observations I was released. The diagnosis: dehy- prepared to sometimes be long and steep Our first day’s ride took us along the coast to and unforgiving, rising Mahone Bay, a tiny village with one long Main Street dration and heat exhaustion. As I learned later, I had come from young middle age (40s and 50s) leave on her close to the third stage of heat-related illnesses: heat stroke, tour of Nova relentlessly one after another lined with shops and cafes and fresh fruit and veg- Nuts and Bolts to my 75. -

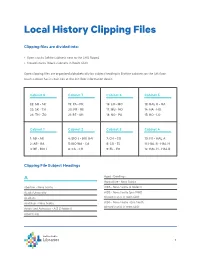

Local History Clipping Files

Local History Clipping Files Clipping files are divided into: • Open stacks (white cabinets next to the LHG Room) • Closed stacks (black cabinets in Room 440) Open clipping files are organized alphabetically by subject heading in 8 white cabinets on the 4th floor (each cabinet has its own key at the 4th floor information desk): Cabinet 8 Cabinet 7 Cabinet 6 Cabinet 5 22: SH - SK 19: PA - PR 16: LO - MO 13: HAL R - HA 23: SK - TH 20: PR - RE 17: MU - NO 14: HA - HO 24: TH - ZO 21: RE - SH 18: NO - PA 15: HO - LO Cabinet 1 Cabinet 2 Cabinet 3 Cabinet 4 1: AB - AR 4: BIO J - BIO U-V 7: CH - CO 10: FO - HAL A 2: AR - BA 5: BIO WA - CA 8: CO - EL 11: HAL B - HAL H 3: BE - BIO I 6: CA - CH 9: EL - FO 12: HAL H - HAL R Clipping File Subject Headings A Aged - Dwellings Agriculture - Nova Scotia Abortion - Nova Scotia AIDS - Nova Scotia (2 folders) Acadia University AIDS - Nova Scotia (pre-1990) Acadians (closed stacks in room 440) Acid Rain - Nova Scotia AIDS - Nova Scotia - Eric Smith (closed stacks in room 440) Actors and Actresses - A-Z (3 folders) Advertising 1 Airlines Atlantic Institute of Education Airlines - Eastern Provincial Airways (closed stacks in room 440) (closed stacks in room 440) Atlantic School of Theology Airplane Industry Atlantic Winter Fair (closed stacks in room 440) Airplanes Automobile Industry and Trade - Bricklin Canada Ltd. Airports (closed stacks in room 440) (closed stacks in room 440) Algae (closed stacks in room 440) Automobile Industry and Trade - Canadian Motor Ambulances Industries (closed stacks in room 440) Amusement Parks (closed stacks in room 440) Automobile Industry and Trade - Lada (closed stacks in room 440) Animals Automobile Industry and Trade - Nova Scotia Animals, Treatment of Automobile Industry and Trade - Volvo (Canada) Ltd. -

Canada's East Coast Forts

Canadian Military History Volume 21 Issue 2 Article 8 2015 Canada’s East Coast Forts Charles H. Bogart Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Charles H. Bogart "Canada’s East Coast Forts." Canadian Military History 21, 2 (2015) This Feature is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : Canada’s East Coast Forts Canada’s East Coast Forts Charles H. Bogart hirteen members of the Coast are lined with various period muzzle- Defense Study Group (CDSG) Abstract: Canada’s East Coast has loading rifled and smoothbore T long been defended by forts and spent 19-24 September 2011 touring cannon. Besides exploring both the other defensive works to prevent the coastal defenses on the southern attacks by hostile parties. The state interior and exterior of the citadel, and eastern coasts of Nova Scotia, of these fortifications today is varied CDSG members were allowed to Canada. Thanks to outstanding – some have been preserved and even peruse photographs, maps, and assistance and coordination by Parks restored, while others have fallen reference materials in the Citadel’s victim to time and the environment. Canada, we were able to visit all library. Our guides made a particular In the fall of 2011, a US-based remaining sites within the Halifax organization, the Coast Defense point to allow us to examine all of area. -

Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site Kejimkujik Visitor Guide Lachlan Riehl / Friends of Keji Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site

Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site Kejimkujik Visitor Guide Lachlan Riehl / Friends of Keji Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site Box 236 Maitland Bridge, NS B0T 1B0 [email protected] www.parkscanada.gc.ca Tel: (902) 682-2772 Fax: (902) 682-3367 Front Entrance Coordinates Easting 325296 Northing 4922771 UTM Zone 20N NAD83 Visitor Centre (902) 682-2772 Open 7 days a week: May 20 – June 23 8:30am – 4:30pm June 24 – Sept 4 8:30am – 8pm Sept 5 – Oct 9 8:30am – 4:30pm Camping Reservations www.reservation.parkscanada.gc.ca or call 1-877-RESERVE Accessibility Hello, Bonjour, K'we! Inquire at the Visitor Centre for options that most suit Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site welcomes you. your abilities. The following With 381 square kilometres of rolling hills and waterways, Kejimkujik is a gentle wilderness where generations of families places are wheelchair have canoed, camped and connected with nature. It protects a collection of rare southern species and is home to the accessible: greatest diversity of reptiles and amphibians in Atlantic Canada. Ÿ Designated campsites Not only does the park protect a unique sample of the Acadian forest, it also preserves and presents a unique cultural landscape, celebrating the presence of the Mi'kmaq and sharing the stories of their ancestors and history in this place. The and selected oTENTiks rich Mi’kmaw heritage, rock engravings known as petroglyphs, traditional encampment areas and canoe routes Ÿ Amphitheatre contributed to the designation of Kejimkujik as a National Historic Site. Ÿ Merrymakedge Beach Ÿ Mersey Meadow Trail With low light pollution, Kejimkujik is very proud to be one of Canada's Dark Sky Preserves.