The Mitotic Checkpoint Is a Targetable Vulnerability of Carboplatin-Resistant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deregulated Gene Expression Pathways in Myelodysplastic Syndrome Hematopoietic Stem Cells

Leukemia (2010) 24, 756–764 & 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0887-6924/10 $32.00 www.nature.com/leu ORIGINAL ARTICLE Deregulated gene expression pathways in myelodysplastic syndrome hematopoietic stem cells A Pellagatti1, M Cazzola2, A Giagounidis3, J Perry1, L Malcovati2, MG Della Porta2,MJa¨dersten4, S Killick5, A Verma6, CJ Norbury7, E Hellstro¨m-Lindberg4, JS Wainscoat1 and J Boultwood1 1LRF Molecular Haematology Unit, NDCLS, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK; 2Department of Hematology Oncology, University of Pavia Medical School, Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy; 3Medizinische Klinik II, St Johannes Hospital, Duisburg, Germany; 4Division of Hematology, Department of Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; 5Department of Haematology, Royal Bournemouth Hospital, Bournemouth, UK; 6Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA and 7Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK To gain insight into the molecular pathogenesis of the the World Health Organization.6,7 Patients with refractory myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), we performed global gene anemia (RA) with or without ringed sideroblasts, according to expression profiling and pathway analysis on the hemato- poietic stem cells (HSC) of 183 MDS patients as compared with the the French–American–British classification, were subdivided HSC of 17 healthy controls. The most significantly deregulated based on the presence or absence of multilineage dysplasia. In pathways in MDS include interferon signaling, thrombopoietin addition, patients with RA with excess blasts (RAEB) were signaling and the Wnt pathways. Among the most signifi- subdivided into two categories, RAEB1 and RAEB2, based on the cantly deregulated gene pathways in early MDS are immuno- percentage of bone marrow blasts. -

Supplemental Information to Mammadova-Bach Et Al., “Laminin Α1 Orchestrates VEGFA Functions in the Ecosystem of Colorectal Carcinogenesis”

Supplemental information to Mammadova-Bach et al., “Laminin α1 orchestrates VEGFA functions in the ecosystem of colorectal carcinogenesis” Supplemental material and methods Cloning of the villin-LMα1 vector The plasmid pBS-villin-promoter containing the 3.5 Kb of the murine villin promoter, the first non coding exon, 5.5 kb of the first intron and 15 nucleotides of the second villin exon, was generated by S. Robine (Institut Curie, Paris, France). The EcoRI site in the multi cloning site was destroyed by fill in ligation with T4 polymerase according to the manufacturer`s instructions (New England Biolabs, Ozyme, Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France). Site directed mutagenesis (GeneEditor in vitro Site-Directed Mutagenesis system, Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France) was then used to introduce a BsiWI site before the start codon of the villin coding sequence using the 5’ phosphorylated primer: 5’CCTTCTCCTCTAGGCTCGCGTACGATGACGTCGGACTTGCGG3’. A double strand annealed oligonucleotide, 5’GGCCGGACGCGTGAATTCGTCGACGC3’ and 5’GGCCGCGTCGACGAATTCACGC GTCC3’ containing restriction site for MluI, EcoRI and SalI were inserted in the NotI site (present in the multi cloning site), generating the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. The SV40 polyA region of the pEGFP plasmid (Clontech, Ozyme, Saint Quentin Yvelines, France) was amplified by PCR using primers 5’GGCGCCTCTAGATCATAATCAGCCATA3’ and 5’GGCGCCCTTAAGATACATTGATGAGTT3’ before subcloning into the pGEMTeasy vector (Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France). After EcoRI digestion, the SV40 polyA fragment was purified with the NucleoSpin Extract II kit (Machery-Nagel, Hoerdt, France) and then subcloned into the EcoRI site of the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. Site directed mutagenesis was used to introduce a BsiWI site (5’ phosphorylated AGCGCAGGGAGCGGCGGCCGTACGATGCGCGGCAGCGGCACG3’) before the initiation codon and a MluI site (5’ phosphorylated 1 CCCGGGCCTGAGCCCTAAACGCGTGCCAGCCTCTGCCCTTGG3’) after the stop codon in the full length cDNA coding for the mouse LMα1 in the pCIS vector (kindly provided by P. -

Defective Lymphocyte Chemotaxis in Я-Arrestin2- and GRK6-Deficient Mice

Defective lymphocyte chemotaxis in -arrestin2- and GRK6-deficient mice Alan M. Fong*, Richard T. Premont*, Ricardo M. Richardson*, Yen-Rei A. Yu†, Robert J. Lefkowitz*‡§, and Dhavalkumar D. Patel*†¶ Departments of *Medicine, ‡Biochemistry, and †Immunology, and §Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710 Contributed by Robert J. Lefkowitz, April 4, 2002 Lymphocyte chemotaxis is a complex process by which cells move kinase, extracellular receptor kinase, and c-jun terminal kinase within tissues and across barriers such as vascular endothelium and activation (9–12), they might also act as positive regulators of is usually stimulated by chemokines such as stromal cell-derived chemotaxis. To evaluate the role of the GRK-arrestin pathway factor-1 (CXCL12) acting via G protein-coupled receptors. Because in chemotaxis, we studied the chemotactic responses of lym- members of this receptor family are regulated (‘‘desensitized’’) by phocytes from -arrestin- and GRK-deficient mice toward G protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK)-mediated receptor phos- gradients of stromal cell-derived factor 1 (CXCL12), a well  phorylation and -arrestin binding, we examined signaling and characterized chemokine whose receptor is CXCR4, a core- chemotactic responses in splenocytes derived from knockout mice ceptor for HIV. deficient in various -arrestins and GRKs, with the expectation that these responses might be enhanced. Knockouts of -arrestin2, Materials and Methods GRK5, and GRK6 were examined because all three proteins are :expressed at high levels in purified mouse CD3؉ T and B220؉ B Mice. The following mouse strains were used in this study splenocytes. CXCL12 stimulation of membrane GTPase activity was -arrestin2-deficient (back-crossed for six generations onto the unaffected in splenocytes derived from GRK5-deficient mice but C57͞BL6 background; ref. -

Viewed Under 23 (B) Or 203 (C) fi M M Male Cko Mice, and Largely Unaffected Magni Cation; Scale Bars, 500 M (B) and 50 M (C)

BRIEF COMMUNICATION www.jasn.org Renal Fanconi Syndrome and Hypophosphatemic Rickets in the Absence of Xenotropic and Polytropic Retroviral Receptor in the Nephron Camille Ansermet,* Matthias B. Moor,* Gabriel Centeno,* Muriel Auberson,* † † ‡ Dorothy Zhang Hu, Roland Baron, Svetlana Nikolaeva,* Barbara Haenzi,* | Natalya Katanaeva,* Ivan Gautschi,* Vladimir Katanaev,*§ Samuel Rotman, Robert Koesters,¶ †† Laurent Schild,* Sylvain Pradervand,** Olivier Bonny,* and Dmitri Firsov* BRIEF COMMUNICATION *Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology and **Genomic Technologies Facility, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland; †Department of Oral Medicine, Infection, and Immunity, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; ‡Institute of Evolutionary Physiology and Biochemistry, St. Petersburg, Russia; §School of Biomedicine, Far Eastern Federal University, Vladivostok, Russia; |Services of Pathology and ††Nephrology, Department of Medicine, University Hospital of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland; and ¶Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France ABSTRACT Tight control of extracellular and intracellular inorganic phosphate (Pi) levels is crit- leaves.4 Most recently, Legati et al. have ical to most biochemical and physiologic processes. Urinary Pi is freely filtered at the shown an association between genetic kidney glomerulus and is reabsorbed in the renal tubule by the action of the apical polymorphisms in Xpr1 and primary fa- sodium-dependent phosphate transporters, NaPi-IIa/NaPi-IIc/Pit2. However, the milial brain calcification disorder.5 How- molecular identity of the protein(s) participating in the basolateral Pi efflux remains ever, the role of XPR1 in the maintenance unknown. Evidence has suggested that xenotropic and polytropic retroviral recep- of Pi homeostasis remains unknown. Here, tor 1 (XPR1) might be involved in this process. Here, we show that conditional in- we addressed this issue in mice deficient for activation of Xpr1 in the renal tubule in mice resulted in impaired renal Pi Xpr1 in the nephron. -

Combined Integrin Phosphoproteomic Analyses and Small Interfering RNA–Based Functional Screening Identify Key Regulators for Cancer Cell Adhesion and Migration

Published OnlineFirst April 7, 2009; DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2515 Published Online First on April 7, 2009 as 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2515 Research Article Combined Integrin Phosphoproteomic Analyses and Small Interfering RNA–Based Functional Screening Identify Key Regulators for Cancer Cell Adhesion and Migration Yanling Chen,1 Bingwen Lu,2 Qingkai Yang,1 Colleen Fearns,3 John R. Yates III,2 and Jiing-Dwan Lee1 Departments of 1Immunology, 2Chemical Physiology, and 3Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, California Abstract cytoskeletal components (2, 7) and regulation of cell survival, Integrins interact with extracellular matrix (ECM) and deliver proliferation, differentiation, cell cycle, and migration (8, 9). Understanding the mechanism by which integrins modulate these intracellular signaling for cell proliferation, survival, and motility. During tumor metastasis, integrin-mediated cell cellular activities is of significant biological importance. adhesion to and migration on the ECM proteins are required The most common cancers in human include breast cancer, for cancer cell survival and adaptation to the new microen- prostate cancer, lung cancer, colon cancer, and ovarian cancer (10, 11), and their metastasis is the leading cause of mortality in vironment. Using stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell cancer patients, causing 90% of deaths from solid tumors (11, 12). culture–mass spectrometry, we profiled the phosphoproteo- During the process of metastasis, tumor cells leave the primary mic changes induced by the interactions of cell integrins with site, travel via blood and/or lymphatic circulatory systems, attach type I collagen, the most common ECM substratum. Integrin- to the substratum of ECM at a distant site, and establish a ECM interactions modulate phosphorylation of 517 serine, secondary tumor, accompanied by angiogenesis of the newly threonine, or tyrosine residues in 513 peptides, corresponding formed neoplasm (12). -

Funkce CDK12 a CDK13 V Regulaci Transkripce Hana Paculová

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA PŘÍRODOVĚDECKÁ FAKULTA ÚSTAV BIOCHEMIE Funkce CDK12 a CDK13 v regulaci transkripce Disertační práce Hana Paculová Školitel: Mgr. Jiří Kohoutek, Ph.D Brno 2018 Bibliogra cký záznam Autorka: Mgr. Hana Paculová Prrodovedecáá aaául,a鏈 Maaarkáova unvverv,a Úa,av bvochemve Název práce: Funáce CDK12 a CDK13 v regulacv ,ranaárvpce Studijní program: Bvochemve Studijní obor: Bvochemve Školitel: Mgr. Jvr Kohou,eá鏈 Ph.D Akademický rok: 2017/2018 Po et stran: 89 Klí ová slova: Ckálvn-dependen,n ávnaaa鏈 CDK12鏈 ,ranaárvpce鏈 RNA polkmeraaa II鏈 raáovvna vaječnáů鏈 CHK1 Bibliographic entry Author: Mgr. Hana Paculová Facul,k oa acvence鏈 Maaarká unvverav,k Department of Biochemistry Title oF dissertation: CDK12 and CDK13 aunc,von vn ,ranacrvp,von regula,von Degree programme: Bvochemva,rk Field oF study: Bvochemva,rk Supervisor: Mgr. Jvr Kohou,eá鏈 Ph.D Academic year: 2017/2018 Number oF pages: 89 Keywords: Ckclvn-dependen ávnaae鏈 CDK12鏈 ,ranacrvp,von鏈 RNA polkmeraae II鏈 ovarvan cancer鏈 CHK1 Abstrakt Ckálvn-dependen,n ávnaaa 12 (CDK12) je ,ranaárvpčn ávnaaa鏈 á,erá rd expreav avých clových genů ,m鏈 že aoaaorkluje RNA polkmeraau II v průbehu elongačn aáe ,ranaárvpce. CDK12 je apojena do neáolváa bunečných preceaů鏈 což ahrnuje odpoveď na pošáoen DNA鏈 vývoj a bunečnou dvaerencvacv a aea,rvh mRNA. CDK12 bkla popaána jaáo jeden genů鏈 á,eré jaou čaa,o mu,ovánk v hvgh-grade aerónm ovarválnm áarcvnomu鏈 nvcméne vlvv ,ech,o mu,ac na aunácv CDK12 a jejvch role v áarcvnogenev dopoaud nebkla a,anovena. Zjva,vlv jame鏈 že ve,švna mu,ac CDK12鏈 á,eré bklk naleenk v nádorech鏈 brán vk,voren áomplexu CDK12 a Ckálvnem K a vnhvbuj ávnaaovou aá,vvv,u CDK12. -

Investigating the Role of Cdk11in Animal Cytokinesis

Investigating the Role of CDK11 in Animal Cytokinesis by Thomas Clifford Panagiotou A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Molecular Genetics University of Toronto © Copyright by Thomas Clifford Panagiotou (2020) Investigating the Role of CDK11 in Animal Cytokinesis Thomas Clifford Panagiotou Master of Science Department of Molecular Genetics University of Toronto 2020 Abstract Finely tuned spatio-temporal regulation of cell division is required for genome stability. Cytokinesis constitutes the final stages of cell division, from chromosome segregation to the physical separation of cells, abscission. Abscission is tightly regulated to ensure it occurs after earlier cytokinetic events, like the maturation of the stem body, the regulatory platform for abscission. Active Aurora B kinase enforces the abscission checkpoint, which blocks abscission until chromosomes have been cleared from the cytokinetic machinery. Currently, it is unclear how this checkpoint is overcome. Here, I demonstrate that the cyclin-dependent kinase CDK11 is required for cytokinesis. Both inhibition and depletion of CDK11 block abscission. Furthermore, the mitosis-specific CDK11p58 kinase localizes to the stem body, where its kinase activity rescues the defects of CDK11 depletion and inhibition. These results suggest a model whereby CDK11p58 antagonizes Aurora B kinase to overcome the abscission checkpoint to allow for successful completion of cytokinesis. ii Acknowledgments I am very grateful for the support of my family and friends throughout my studies. I would also like to express my deep gratitude to Wilde Lab members, both past and present, for their advice and collaboration. In particular, I am very grateful to Matthew Renshaw, whose work comprises part of this thesis. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

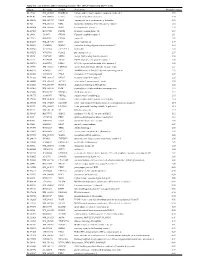

Supplementary Table 1

Table S1. List of Genes Differentially Expressed in YB-1 siRNA-Transfected MCF-7 Cells Unigene Accession Symbol Description Mean fold change Hs.17466 NM_004585 RARRES3 retinoic acid receptor responder (tazarotene induced) 3 3.57 Hs.64746 NM_004669 CLIC3 chloride intracellular channel 3 3.33 Hs.516155 NM_001747 CAPG capping protein (actin filament), gelsolin-like 2.88 Hs.926 NM_002463 MX2 myxovirus (influenza virus) resistance 2 (mouse) 2.72 Hs.643494 NM_005410 SEPP1 selenoprotein P, plasma, 1 2.70 Hs.267038 BC017500 POF1B premature ovarian failure 1B 2.67 Hs.20961 U63917 GPR30 G protein- coupled receptor 30 2532.53 Hs.199877 BE645967 CPNE4 copine IV 2.49 Hs.632177 NM_017458 MVP major vault protein 2.48 Hs.528836 AA005023 NOD27 nucleotide-binding oligomerization domains 27 2.43 Hs.360940 AL589866 dJ222E13.1 kraken-like 2.40 Hs.515575 AI743780 PLAC2 placenta-specific 2 2.37 Hs.25674 AI827820 MBD2 methyl-CpG binding domain protein 2 2.36 Hs.12229 AA149594 TIEG2 TGFB inducible early growth response 2 2.33 Hs.482730 AA053711 EDIL3 EGF-like repeats and discoidin I-like domains 3 2.32 Hs. 370771 NM_000389 CDKN1A cyclin- depen dent kinase in hibitor 1A (p 21, Cip 1) 2282.28 Hs.469175 AI341537 JFC1 NADPH oxidase-related, C2 domain-containing protein 2.28 Hs.514821 AF043341 CCL5 chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 2.27 Hs.591292 NM_023915 GPR87 G protein-coupled receptor 87 2.26 Hs.500483 NM_001613 ACTA2 actin, alpha 2, smooth muscle, aorta 2.24 Hs.632824 NM_006729 DIAPH2 diaphanous homolog 2 (Drosophila) 2.22 Hs.369430 NM_000919 PAM peptidylglycine -

Developing Biomarkers for Livestock Science

Developing biomarkers for livestock Science Ongoing research and future developments Marinus te Pas Outline . Introduction ● What are biomarkers ● Why do we need them . Examples ● omics levels . The future ● Big data ● Systems biology / Synthetic biology 2 Introduction: What are biomarkers? . Biological processes underlie all livestock (production) traits ● Measure the status of a biological process = know the trait! . Can be any molecule in a cell ● No need to know the causal factor for a trait . Well known example: blood glucose level for diabetes Introduction: Why do we need biomarkers? . The mission of WageningenUR: Sustainably produce enough high quality food for all people on the planet with an ecological footprint as low as possible 4 What can the industry do with biomarkers? . Diagnostic tool ● What is the biological mechanism underlying a trait? . Prediction tool ● What outcome can I expect from an intervention? . Monitoring tool ● What is the actual status of a process? . Speed up your process, improve your traits Some examples * Transcriptomics * Proteomics * Metabolomics Why Biomarkers for meat quality? . Meat quality has low heritability (h2=0.1-0.2) ● Predictive capacity of genetic markers low . High environmental influence ● Feed, animal handling (stress), management (housing), ... Meat quality can only be measured after 1-several days post slaughter . Need to differentiate between retail, processing industry, restaurants, .... Biomarkers can do all that and more faster, predictive, .. Example Transcriptomics biomarkers for meat quality . Pork production chain . Biomarkers for traits . High quality fresh pork . Meat colour N production chain ● A* 14 . German Pietrain ● L* 4 (microarray) ● Reflection 10 . Verification: Danish . Drip loss 2 Yorkshire (PCR) . Ultimate pH 6 . -

Profiling Data

Compound Name DiscoveRx Gene Symbol Entrez Gene Percent Compound Symbol Control Concentration (nM) JNK-IN-8 AAK1 AAK1 69 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(E255K)-phosphorylated ABL1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(F317I)-nonphosphorylated ABL1 87 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(F317I)-phosphorylated ABL1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(F317L)-nonphosphorylated ABL1 65 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(F317L)-phosphorylated ABL1 61 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(H396P)-nonphosphorylated ABL1 42 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(H396P)-phosphorylated ABL1 60 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(M351T)-phosphorylated ABL1 81 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(Q252H)-nonphosphorylated ABL1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(Q252H)-phosphorylated ABL1 56 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(T315I)-nonphosphorylated ABL1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(T315I)-phosphorylated ABL1 92 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(Y253F)-phosphorylated ABL1 71 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1-nonphosphorylated ABL1 97 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1-phosphorylated ABL1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL2 ABL2 97 1000 JNK-IN-8 ACVR1 ACVR1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ACVR1B ACVR1B 88 1000 JNK-IN-8 ACVR2A ACVR2A 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ACVR2B ACVR2B 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ACVRL1 ACVRL1 96 1000 JNK-IN-8 ADCK3 CABC1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ADCK4 ADCK4 93 1000 JNK-IN-8 AKT1 AKT1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 AKT2 AKT2 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 AKT3 AKT3 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ALK ALK 85 1000 JNK-IN-8 AMPK-alpha1 PRKAA1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 AMPK-alpha2 PRKAA2 84 1000 JNK-IN-8 ANKK1 ANKK1 75 1000 JNK-IN-8 ARK5 NUAK1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ASK1 MAP3K5 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ASK2 MAP3K6 93 1000 JNK-IN-8 AURKA AURKA 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 AURKA AURKA 84 1000 JNK-IN-8 AURKB AURKB 83 1000 JNK-IN-8 AURKB AURKB 96 1000 JNK-IN-8 AURKC AURKC 95 1000 JNK-IN-8 -

The Role of Cyclin B3 in Mammalian Meiosis

THE ROLE OF CYCLIN B3 IN MAMMALIAN MEIOSIS by Mehmet Erman Karasu A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Louis V. Gerstner Jr. Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy New York, NY November, 2018 Scott Keeney, PhD Date Dissertation Mentor Copyright © Mehmet Erman Karasu 2018 DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this thesis to my parents, Mukaddes and Mustafa Karasu. I have been so lucky to have their support and unconditional love in this life. ii ABSTRACT Cyclins and cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs) lie at the center of the regulation of the cell cycle. Cyclins as regulatory partners of CDKs control the switch-like cell cycle transitions that orchestrate orderly duplication and segregation of genomes. Similar to somatic cell division, temporal regulation of cyclin-CDK activity is also important in meiosis, which is the specialized cell division that generates gametes for sexual production by halving the genome. Meiosis does so by carrying out one round of DNA replication followed by two successive divisions without another intervening phase of DNA replication. In budding yeast, cyclin-CDK activity has been shown to have a crucial role in meiotic events such as formation of meiotic double-strand breaks that initiate homologous recombination. Mammalian cells express numerous cyclins and CDKs, but how these proteins control meiosis remains poorly understood. Cyclin B3 was previously identified as germ cell specific, and its restricted expression pattern at the beginning of meiosis made it an interesting candidate to regulate meiotic events.