Unusual Songs in Passerine Birds1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brown-Headed Cowbird (Molothrus Ater) Doug Powless

Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater) Doug Powless Grandville, Kent Co., MI. 5/4/2008 © John Van Orman (Click to view a comparison of Atlas I to II) Brown-headed Cowbirds likely flourished Distribution Brown-headed Cowbirds breed in grassland, alongside the Pleistocene megafauna that once prairie, and agricultural habitats across southern roamed North America (Rothstein and Peer Canada to Florida, the Gulf of Mexico, and 2005). In modern times, flocks of cowbirds south into central Mexico (Lowther 1993). The followed the great herds of bison across the center of concentration and highest abundance grasslands of the continent, feeding on insects of the cowbird during summer occurs in the kicked up, and depositing their eggs in other Great Plains and Midwestern prairie states birds’ nests along the way. An obligate brood where herds of wild bison and other ungulates parasite, the Brown-headed Cowbird is once roamed (Lowther 1993, Chace et al. 2005). documented leaving eggs in the nests of hundreds of species (Friedmann and Kiff 1985, Wild bison occurred in southern Michigan and Lowther 1993). The evolution of this breeding across forest openings in the East until about strategy is one of the most fascinating aspects of 1800 before being hunted to near-extinction North American ornithology (Lanyon 1992, across the continent (Baker 1983, Kurta 1995). Winfree 1999, Rothstein et al. 2002), but the Flocks of cowbirds likely also inhabited the cowbird has long drawn disdain. Chapman prairies and woodland openings of southern (1927) called it “. a thoroughly contemptible Michigan prior to the 1800s (Walkinshaw creature, lacking in every moral and maternal 1991). -

Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers

Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Brandan L. Gray August 2019 © 2019 Brandan L. Gray. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers by BRANDAN L. GRAY has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Donald B. Miles Professor of Biological Sciences Florenz Plassmann Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT GRAY, BRANDAN L., Ph.D., August 2019, Biological Sciences Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers Director of Dissertation: Donald B. Miles In a rapidly changing world, species are faced with habitat alteration, changing climate and weather patterns, changing community interactions, novel resources, novel dangers, and a host of other natural and anthropogenic challenges. Conservationists endeavor to understand how changing ecology will impact local populations and local communities so efforts and funds can be allocated to those taxa/ecosystems exhibiting the greatest need. Ecological morphological and functional morphological research form the foundation of our understanding of selection-driven morphological evolution. Studies which identify and describe ecomorphological or functional morphological relationships will improve our fundamental understanding of how taxa respond to ecological selective pressures and will improve our ability to identify and conserve those aspects of nature unable to cope with rapid change. The New World wood warblers (family Parulidae) exhibit extensive taxonomic, behavioral, ecological, and morphological variation. -

Kentucky Warbler (Vol. 44, No. 1) Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected]

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Kentucky Warbler Library Special Collections 2-1968 Kentucky Warbler (Vol. 44, no. 1) Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ky_warbler Part of the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Kentucky Library Research Collections, "Kentucky Warbler (Vol. 44, no. 1)" (1968). Kentucky Warbler. Paper 129. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ky_warbler/129 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Warbler by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Kentucky Warbler (Published by the Kentucky Ornithological Society) VOL. XLIV FEBRUARY, 1968 NO. 1 # Young Great Horned Owl at Nest. Photograph by Terry Snell IN THIS ISSUE NEWS AND VIEWS 2 CONNECTICUT WARBLERS IN THE LOUISVILLE AREA IN AUTUMN, Kenneth P. Able 3 OBSERVATIONS ON THE GREAT HORNED OWL, Donald Boarman .... 5 MID-WINTER BIRD COUNT, 1967-1968 6 FIELD NOTES; First Record of the Rock Wren in Kentucky, J. W. Kemper and Frederick W. Loetscher 18 Some Notes from Boyle County, J. W. Kemper 18 BOOK REVIEW, Anne L. Stamm 19 2 THE KENTUCKY WARBLER Vol. 44 THE KENTUCKY ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY (Founded in 1923 by B. C. Bacon, L. Otley Pindar, and Gordon Wilson) President Herbert E. Shadowen, Bowling Green Vice-President Mrs. James Gillenwater, Glasgow Corr. Sec.-Treasurer Evelyn Schneider, 2525 Broadmeade Road, Louisville 40205 Recording Secretary Willard Gray, Carlisle Councillors: Albert L. Powell, Maceo ... r. 1966-1968 Alfred M. Reece, Lexington 1966-1968 Ray Nail, Golden Pond 1967-1969 Burt L. -

Birding Brochure

2OAD 0ROPERTYBOUNDARY 3ALATOEXHIBITPATH around HEADQUARTERS 2ESTROOM TRAILS 3ALATOEXHIBITTRAILS 0ICNICSHELTER (ABITREK4RAIL 4RAILMARKER 0EA2IDGE4RAIL 7ARBLER2IDGE4RAIL "ENCH KENTUCKY 0RAIRIE4RAIL 'ATE FISH and WILDLIFE 2ED HEADQUARTERS 2ED "LUE "LUE 2ED 3ALATO 2ED 7ILDLIFE %DUCATION AREA #ENTER HABITAT Moist soil areas Water levels in ponds and wetlands naturally rise and fall on a seasonal basis. When biologists attempt to mimic this natural TYPES system it is called moist soil management. Lowering water levels during the summer months encourages vegetation to grow. Shore- Riparian zones birds will frequent the draining areas in the late summer and fall. Riparian zones occur along creek and river margins and During the fall and winter, the flooded vegetation in larger moist often contain characteristic vegetation such as river birch, soil units can provide food and cover for migrating and wintering sycamore and silver maple. Because of their proximity to waterfowl. Biologists can target species groups by simply altering water, these areas serve as habitat for frogs, egg laying sites water levels. Common yellowthroat can be observed during migra- !RNOLD-ITCHELL"LDG for salamanders, and watering holes for other wildlife includ- tion and the breeding season. Sandpipers feed along the shoreline ing birds. To see one of our best examples, hike the Pea Ridge during migration. loop trail and look for areas that fit this description. The Aca- dian flycatcher is just one species that often uses these areas. Woodland This type of habitat is great for many 5PPER Grassland Lakes species of birds, as the tree canopy over- 3PORTSMANS Once common to the Bluegrass Lakes are formed when water gathers head provides excellent hiding places. -

FLORIDA FIELD NATURALIST a Fledgling Brown-Headed Cowbird

FLORIDA FIELD NATURALIST NOTES A fledgling Brown-headed Cowbird specimen from Pinellas County.-First evi- dences of breeding in Florida by the Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothms ater) were in 1956 and 19.57 near Pensacola (Sprunt 1963, Weston 1965). Since then the species has become a common breeder throughout northern Florida and now is spreading rapidly southward in the peninsula. Here \I-e repo~tfirst evidence of breeding in Pinellas County, halfway down Florida peninsula, and describe Tampa Bay area population increases of the species during recent summers. A young fledgling Brox-n-headed Cowbird was brought to the Suncoast Seabird Sanctuary in Pinellas County on 2 June 198.5. It died the same day. Precise locality data were not kept, but little doubt exists the bird was obtained locally. Rarely are birds brought to the sanctuary from outside the county, and for these more precise locality data are kept. The specimen, a female (ovary 3..5 X 3mm, not granular), weighed only 17.5 grams. It is preserved as a study skin (GEW 5736) at the University of South Florida. The primaries and rectrices have remnants of sheaths and the tail (.56.5 mm total length) is about 10 mm shorter than average for adult females. Cowbirds typically weigh about 30 grams at fledging (Mayfield 1960). The incomplete feather growth and light weight support a local origin for the bird. The Nesting Season reports in American Birds and its predecessor Audubon Field Notes provide a good account of the expansion of the Brown-headed Cowbird's breeding range in Florida. -

The Kentucky Warbler (Published by Kentucky Ornithological Society)

The Kentucky Warbler (Published by Kentucky Ornithological Society) VOL. 83 NOVEMBER 2007 NO. 4 IN THIS ISSUE BEWICK’S WRENS IN KENTUCKY AND TENNESSEE: DISTRIBUTION, BREEDING SUCCESS, HABITAT USE, AND INTERACTIONS WITH HOUSE WRENS, Michael E. Hodge and Gary Ritchison ......................................... 91 SUMMER SEASON 2007, Brainard Palmer-Ball, Jr., and Lee McNeely ....................... 102 THE KENTUCKY ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY FALL 2007 MEETING John Brunjes ............................................................................................................. 107 FIELD NOTES Late Indigo Bunting Nest in Christian County .......................................................... 110 Rough-legged Hawk Documentation from Shelby County........................................ 111 NEWS AND VIEWS......................................................................................................... 111 90 THE KENTUCKY WARBLER Vol. 83 THE KENTUCKY ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY President................................................................................................Win Ahrens, Prospect Vice-President ....................................................................................Scott Marsh, Lexington Corresponding Secretary ..................................................................Brainard Palmer-Ball, Jr. 8207 Old Westport Road, Louisville, KY 40222-3913 Treasurer.............................................................................................................Lee McNeely P.O. Box 463, Burlington, -

An Analysis of Physical, Physiological, and Optical Aspects of Avian Coloration with Emphasis on Wood-Warblers

(ISBN: 0-943610-47-8) AN ANALYSIS OF PHYSICAL, PHYSIOLOGICAL, AND OPTICAL ASPECTS OF AVIAN COLORATION WITH EMPHASIS ON WOOD-WARBLERS BY EDWARD H. BURTT, JR. Department of Zoology Ohio Wesleyan University Delaware, Ohio 43015 ORNITHOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS NO. 38 PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION WASHINGTON, D.C. 1986 AN ANALYSIS OF PHYSICAL, PHYSIOLOGICAL, AND OPTICAL ASPECTS OF AVIAN COLORATION WITH EMPHASIS ON WOOD-WARBLERS ORNITHOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS This series,published by the American Ornithologists' Union, has been estab- lished for major papers too long for inclusion in the Union's journal, The Auk. Publication has been made possiblethrough the generosityof the late Mrs. Carl Tucker and the Marcia Brady Tucker Foundation, Inc. Correspondenceconcerning manuscripts for publication in the seriesshould be addressedto the Editor, Dr. David W. Johnston,Department of Biology, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA 22030. Copies of Ornithological Monographs may be ordered from the Assistant to the Treasurer of the AOU, Frank R. Moore, Department of Biology, University of Southern Mississippi, Southern Station Box 5018, Hattiesburg, Mississippi 39406. (See price list on back and inside back covers.) Ornithological Monographs, No. 38, x + 126 pp. Editors of OrnithologicalMonographs, David W. Johnstonand Mercedes S. Foster Special Reviewers for this issue, Sievert A. Rohwer, Department of Zo- ology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington; William J. Hamilton III, Division of Environmental Studies, University of Cal- ifornia, Davis, California Author, Edward H. Burtt, Jr., Department of Zoology, Ohio Wesleyan University, Delaware, Ohio 43015 First received, 24 October 1982; accepted 11 March 1983; final revision completed 9 April 1985 Issued May 1, 1986 Price $15.00 prepaid ($12.50 to AOU members). -

Kentucky Warbler Kentucky Library - Serials

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Kentucky Warbler Kentucky Library - Serials 5-2011 Kentucky Warbler (Vol. 87, no. 2) Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ky_warbler Part of the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Kentucky Library Research Collections, "Kentucky Warbler (Vol. 87, no. 2)" (2011). Kentucky Warbler. Paper 346. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ky_warbler/346 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Warbler by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Kentucky Warbler (Published by Kentucky Ornithological Society) VOL. 87 MAY 2011 NO. 2 IN THIS ISSUE IN MEMORIAM: JAMES W. HANCOCK ....................................................................... 47 COMPARISON OF THE NEOTROPICAL MIGRANT BREEDING BIRD COMMUN- ITIES OF THE PRESERVE AND THE RECREATION AREA OF JOHN JAMES AUDUBON STATE PARK, 2004–2007, Micah W. Perkins ......................................... 47 WINTER SEASON 2010–2011, Brainard Palmer-Ball, Jr., and Lee McNeely .................. 56 THE KENTUCKY ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY SPRING 2011 MEETING, John Brunjes, Recording Secretary ..............................................................................67 BOOK REVIEW, The Crossley ID Guide, Carol Besse .................................................... 69 NEWS AND VIEWS ..........................................................................................................71 -

Learn About Texas Birds Activity Book

Learn about . A Learning and Activity Book Color your own guide to the birds that wing their way across the plains, hills, forests, deserts and mountains of Texas. Text Mark W. Lockwood Conservation Biologist, Natural Resource Program Editorial Direction Georg Zappler Art Director Elena T. Ivy Educational Consultants Juliann Pool Beverly Morrell © 1997 Texas Parks and Wildlife 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 PWD BK P4000-038 10/97 All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems – without written permission of the publisher. Another "Learn about Texas" publication from TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE PRESS ISBN- 1-885696-17-5 Key to the Cover 4 8 1 2 5 9 3 6 7 14 16 10 13 20 19 15 11 12 17 18 19 21 24 23 20 22 26 28 31 25 29 27 30 ©TPWPress 1997 1 Great Kiskadee 16 Blue Jay 2 Carolina Wren 17 Pyrrhuloxia 3 Carolina Chickadee 18 Pyrrhuloxia 4 Altamira Oriole 19 Northern Cardinal 5 Black-capped Vireo 20 Ovenbird 6 Black-capped Vireo 21 Brown Thrasher 7Tufted Titmouse 22 Belted Kingfisher 8 Painted Bunting 23 Belted Kingfisher 9 Indigo Bunting 24 Scissor-tailed Flycatcher 10 Green Jay 25 Wood Thrush 11 Green Kingfisher 26 Ruddy Turnstone 12 Green Kingfisher 27 Long-billed Thrasher 13 Vermillion Flycatcher 28 Killdeer 14 Vermillion Flycatcher 29 Olive Sparrow 15 Blue Jay 30 Olive Sparrow 31 Great Horned Owl =female =male Texas Birds More kinds of birds have been found in Texas than any other state in the United States: just over 600 species. -

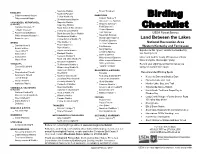

Birding Checklist

Nashville Warbler Brown Thrasher*† KINGLETS Northern Parula*† Golden-crowned Kinglet EMBERIZIDS Yellow Warbler*† Eastern Towhee*† Birding Ruby-crowned Kinglet Chestnut-sided Warbler American Tree Sparrow CHICKADEES, NUTHATCHES, Magnolia Warbler Chipping Sparrow*† & ALLIES Cape May Warbler Field Sparrow*† Carolina Chickadee*† Black-throated Blue Warbler Checklist Vesper Sparrow Tufted Titmouse*† Yellow-rumped Warbler Lark Sparrow Red-breasted Nuthatch Black-throated Green Warbler USDA Forest Service Savannah Sparrow White-breasted Nuthatch*† Blackburnian Warbler Grasshopper Sparrow Brown Creeper Yellow-throated Warbler*† Land Between the Lakes Henslow’s Sparrow Pine Warbler*† WRENS Le Conte’s Sparrow National Recreation Area Prairie Warbler*† Carolina Wren*† Fox Sparrow Western Kentucky and Tennessee Palm Warbler Bewick’s Wren Song Sparrow Bay-breasted Warbler Experience this “green” corridor surrounded by House Wren*† Lincoln’s Sparrow Winter Wren Blackpoll Warbler two flowing rivers. Swamp Sparrow Cerulean Warbler*† Sedge Wren White-throated Sparrow Listen and look for nearly 250 species of birds Black-and-white Warbler*† Marsh Wren White-crowned Sparrow travel along the Mississippi Flyway. American Redstart*† Dark-eyed Junco THRUSHES Prothonotary Warbler*† Record your sightings on this bird list as you Eastern Bluebird*† Lapland Longspur surround yourself with nature. Worm-eating Warbler*† Veery Swainson’s Warbler BLACKBIRDS & ORIOLES Gray-cheeked Thrush Ovenbird*† Bobolink -

Small Forest Openings Support Shrubland Birds and Native Bees In

United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service Small Forest Openings Support Conservation Effects Assessment Project (CEAP) CEAP-Wildlife Conservation Insight Shrubland Birds and Native Bees in December 2017 the Northeast Summary of Findings ings than in mature forest. Individ- Background ual opening size did not affect bee • Once prevalent on the landscape, abundance or diversity; however, bees Wildlife species that depend on early early successional habitats are now were more abundant and diverse in successional shrubland habitats have rare in the northeastern United openings and adjacent mature forest experienced severe population de- States. As a result, populations of when there was more early succes- clines in eastern North America due many wildlife species that rely on sional habitat in the surrounding land- to the loss of disturbance-dependent these habitats (dominated by shrubs, scape. Bee abundance and diversity young forest habitats. Disturbances young trees, grasses, and forbs) in forest openings tended to decrease such as wind-throw, wildfire, beaver have declined. with vegetation height and increase activity, and flooding, which once • Group selection timber harvest with a metric representing floral naturally sustained these ephemeral can be used to create small forest richness and abundance. In adjacent habitats, have largely been suppressed openings (typically <1 ha) and has mature forests, eusocial, soft-wood- by humans. As a result, maintaining the potential to provide needed nesting, and small bees exhibited the disturbance-dependent early succes- shrubland habitats within the opposite pattern, increasing with the sional habitats is now considered a parcelled forest ownerships of succession of openings and decreasing conservation priority in the northeast. -

Virgin Islands Bird Check List

2002 Revised Revised Birds of St. John, U.S.V.I. Birds in which the bird is most likely to be to found: isin most the bird which likely Compiled by L. Brannick & Dr. D. Catanzaro Compiled by L. Brannick & Dr. eastern the on is located of St. John island The latitude North 18 degrees at Antilles Greater ofend the in is 9 miles St. John longitude. West 64 degrees and Islands Virgin point. widest its at 5 miles and length tracts protects large Park National of natural habitat can be seen of birds 144 species approximately in which year. the throughout based been updated has recently checklist This local the staff, of Park records and observations the on & of Fish .Division V.I the and Society Audubon this to been added have species new A few Wildlife. gone long have that others while list, revised us in been dropped. Please help have unreported your with list this mailing by records, accurate keeping park. the to observations recorded the follow nomenclature and Species taxonomy checklist. supplements ) and edition ( 1998, 7th U. A. O. their with names common their by listed are birds The lines separate Solid in parenthesis. names scientific families LEGEND Habitat ( OS ) Ocean/Shoreline Forest ( MF ) Moist ( DF ) Dry Forest Areas Inhabited ) IA ( (SP ) Pond Salt Status : ( A -) Abundant species encountered A frequently ( M( ) Mangroves C ) -Common habitat be seen in suitable to seen likely not always but Present ( U )Uncommon- year every not be present - May ( O ) Occasional -( R ) Rare seen Seldom Reported ( * ) Not Status: Breeding Islands Virgin in the ( B ) Breeds Breeder ( P ) Probable ( N ) Non-Breeder Season : Mar.-May ( s ) Spring Dec.-Feb.