Globalizing Sports Law James A.R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

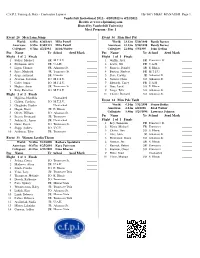

C.F.P.I. Timing & Data - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER Page 1 Vanderbilt Invitational 2012 - 4/20/2012 to 4/21/2012 Results at www.cfpitiming.com Hosted by Vanderbilt University Meet Program - Day 1 Event 26 Men Long Jump Event 36 Men Shot Put World: 8.95m 8/30/1991 Mike Powell World: 23.12m 5/20/1990 Randy Barnes American: 8.95m 8/30/1991 Mike Powell American: 23.13m 5/20/1990 Randy Barnes Collegiate: 8.74m 4/2/1994 Erick Walder Collegiate: 22.00m 6/3/1995 John Godina Pos NameYr School Seed Mark Pos NameYr School Seed Mark Flight 1 of 2 Finals Flight 1 of 1 Finals 1 Stokes, Michael SR M.T.S.U. _________ 1 Griffin, Alex FR Tennessee St. _________ 2 Buchanan, Alex FR U.A.H. _________ 2 Lester, Wil FR U.A.H. _________ 3 Ligon, Thomas FR Arkansas St. _________ 3 Romero, Donald SR E. Illinois _________ 4 Price, Markeith JR Tennessee St. _________ 4 Bastien, Shubert FR M.T.S.U. _________ 5 diogo, raymond SR Uganda _________ 5 Pace, Corwin JR Arkansas St. _________ 6 Atosona, Solomon SO M.T.S.U. _________ 6 Nicasio, Chris SO Arkansas St. _________ 7 Cadet, Junior SO M.T.S.U. _________ 7 Edwards, Casey FR U.A.H. _________ 8 Hughes, Avian SR Tennessee St. _________ 8 Diaz, Jared SO E. Illinois _________ 9 Rory, Kameron SO M.T.S.U. _________ 9 Lingo, Tyler SO Arkansas St. _________ Flight 2 of 2 Finals 10 Chavez, Richard SO Arkansas St. -

SCOREBOARD Cent of the Vote Respectively

20—MANCHESTER HERALD, Tuesday, November 6,1990 Reynolds, Barnes face ban from the 1992 Olympics WEDNESDAY LONDON (AP) — Facing a possible two-year suspen metabolites of the banned substance methyli'*ctosicrone, sion that could prevent him from competing in the 1992 .. There is no room for steroids or and a second analysis carried out on Sept. 25, 1990, con Olympics, Butch Reynolds, the world record-holder in firmed their presence. the 400 meters, deni^ he has ever used steroids and said drug abuse in my life___People who LOCAL NEWS INSIDE “The case was then investigated by the lAAF doping drug tests that turned up positive “cannot be medically know Butch Reynolds know that I have al commission, who confirmed the positive result. ■ Democrat incumbents were jubilant. supported." ways been one of the strongest proponents “On Oct. 24, the lAAF informed TAC of the result of IHanrlipalpr Reynolds and Randy Barnes, the world record-holder the second test and requested TAC to note the suspension in the shot put, were suspended by the International of random year-round drug testing. of the athlete in accordance with lAAF rule 59 and to ■ GOP saw little reason for rejoicing. Amateur Athletic Federation for testing positive for offer the athlete an opportunity of a hearing in accord steroids. “I have taken drug tests five times over ance with the rules and procedures of the lAAF. What's The lAAF, track and field’s world governing body, on the past 10 months. Believe me, the results ‘TAC confirmed that this has been done and the date ■ Herbst trounces Bunnell in 35th. -

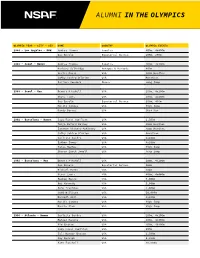

Alumni in the Olympics

ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS 1984 - Los Angeles - M&W Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m, 200m 1988 - Seoul - Women Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Barbara Selkridge Antigua & Barbuda 400m Leslie Maxie USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Juliana Yendork Ghana Long Jump 1988 - Seoul - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 200m, 400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Randy Barnes USA Shot Put 1992 - Barcelona - Women Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 1,500m Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeene Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Carlette Guidry USA 4x100m Esther Jones USA 4x100m Tanya Hughes USA High Jump Sharon Couch-Jewell USA Long Jump 1992 - Barcelona - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m Michael Bates USA 200m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Reuben Reina USA 5,000m Bob Kennedy USA 5,000m John Trautman USA 5,000m Todd Williams USA 10,000m Darnell Hall USA 4x400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Darrin Plab USA High Jump 1996 - Atlanta - Women Carlette Guidry USA 200m, 4x100m Maicel Malone USA 400m, 4x400m Kim Graham USA 400m, 4X400m Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 800m Juli Henner Benson USA 1,500m Amy Rudolph USA 5,000m Kate Fonshell USA 10,000m ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS Ann-Marie Letko USA Marathon Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeen Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Shana Williams -

Individual Champions

S TANFORD AT NCAA CHAMPION S HIP S Individual Champions Men’s NCAA Champions Name Event Mark/Time Year Site Albritton, Terry Shot Put 67-3 1/2 1977 Champaign, Il Brown, Russell DMR 9:33.64 2007 Fayetteville, Ark Chandy, Zach DMR 9:33.64 2007 Fayetteville, Ark Dobson, Ian 5,000 Meters (Indoors) 13:43.36 2005 Fayetteville, Ark Dunn, Gordon Discus 162-7 1934 Los Angeles, Ca Edmonds, Ward Pole Vault 13-6 1/4 1928 Chicago, Il Pole Vault 13-8 7/8 1929 Chicago, Il Garcia, Michael DMR 9:33.64 2007 Fayetteville, Ark Hall, Ryan 5,000 Meters 13:22.32 2005 Sacramento, Ca Hanner, Flint Javelin 191-2 1/4 1921 Chicago, Il Hartranft, Glenn Shot Put 50-0 1921 Chicago, Il Hassell, Mark Distance Medley Relay 9:30.01 2001 Fayetteville, Ark Hauser, Brad 5,000 Meters (Indoors) 13:58.50 1998 Indianapolis, In 10,000 Meters 28:31.30 1998 Buffalo, NY 5,000 Meters (Indoors) 13:52.79 1999 Indianapolis, In 5,000 Meters 13:48.80 2000 Durham, NC 10,000 Meters 30:38.57 2000 Durham, NC Heath, Garrett DMR 9:33.64 2007 Fayetteville, Ark Held, Bud Javelin 209-8 1948 Minneapolis, Mn Javelin 224-8 1/4 1949 Los Angeles, Ca Javelin 216-8 5/8 1950 Minneapolis, Mn Hoffman, Clifford Discus 148-4 1921 Chicago, Il Jennings, Gabe Mile (Indoors) 3:59.46 2000 Fayetteville, Ark PattiSue Plumer won the 2-Mile Indoors title in Distance Medley Relay 9:28.83 2000 Fayetteville, Ark Terry Albritton won the NCAA shot put title in 1977. -

University of Texas at Austin Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 6:20 PM 3/26/2021 Page 1 93Rd Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays Univ.Of Texas-Mike A

University of Texas at Austin Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 6:20 PM 3/26/2021 Page 1 93rd Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays Univ.of Texas-Mike A. Myers Stadium-Austin,TX - 3/25/2021 to 3/27/2021 Results - Friday 5 #12942 Marco Arevalo JR TAMU-Kingsvlle 16.40m Event 69 Women Shot Put Section B Univ/Coll 6 #12952 Jorge Rios JR TAMU-Kingsvlle 16.32m World: 22.63m W 1987 Natalya Lisovskaya 7 #12904 Kevin Steward SR S.F. Austin 16.07m American: 20.63m A 2016 Michelle Carter 8 #12626 Chris Samaniego JR North Texas 15.90m Collegiate: 19.46m C 2018 Maggie Ewen 9 #13181 Brandon Busby TX State 15.89m Myers Std: 18.96m F 2013 Tia Brooks 10 #13524 Tyler Pickens SR West TX A&M 15.67m TX Relays: 18.58m M 2006 Laura Gerraughty 11 #13432 Jorge Ayala JR UTSA 15.37m Name Yr School Finals 12 #13097 Sean Stavinoha FR Texas 14.90m Finals 13 #12930 Steven Sanchez SR TAMU-Commerce 14.82m 1 #12515 Alanna Arvie SR McNeese St. 15.72m --- #13224 Braden Darrow SR TX Tech FOUL 2 #12333 Nu'uausala Tuilefano SO Houston 15.66m 3 #12435 Naomi Mojica JR Liberty 15.44m Event 55 Women Pole Vault Univ/Coll 4 #12152 Ebonie Whitted SO Bowling Green 15.19m World: 5.06m W 2009 Yelena Isinbaeva 5 #13042 Kiana Lowery FR Texas 15.12m American: 5.00m A 2016 Sandi Morris 6 #12462 Amber Hart JR LSU 15.08m Collegiate: 4.73m C 2019 Olivia Gruver 7 #12612 Jaleisa Shaffer SR North Texas 14.92m Myers Std: 4.91m F 2019 Jenn Suhr 8 #12836 Josey Starner SO South Dakota 14.74m TX Relays: 4.60m M 2018 Lisa Gunnarsson 9 #12543 Emily Offenheiser SO Missouri 14.40m Name Yr School Finals 10 #12432 Chelsea -

On Your Mark, Get Set, Stop! Drug-Testing Appeals in the International Amateur Athletic Federation

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 16 Number 2 Symposium—Mexican Elections, Human Rights, and International Law: Article 12 Opposition Views 2-1-1994 On Your Mark, Get Set, Stop! Drug-Testing Appeals in the International Amateur Athletic Federation Hilary Joy Hatch Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Hilary Joy Hatch, On Your Mark, Get Set, Stop! Drug-Testing Appeals in the International Amateur Athletic Federation, 16 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 537 (1994). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol16/iss2/12 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES AND COMMENTS On Your Mark, Get Set, Stop! Drug- Testing Appeals in the International Amateur Athletic Federation I. INTRODUCTION Amateur athletes must abide by strict rules set out by various organizations to be eligible to compete in athletic events. Elite athletes wishing to compete in the Olympic Games have many con- cerns besides their athletic performance. These athletes must fol- low drug-testing rules set forth by their nation's Olympic Committee, the International Olympic Committee, and interna- tional athletic federations.' If an athlete tests positive for drugs before, during, or after competition, he or she may be declared in- eligible, and a world record can be invalidated. -

“Where the World's Best Athletes Compete”

6 0 T H A N N U A L “Where the world’s best athletes compete” MEDIA INFORMATION updated on April 5, 2018 6 0 T H A N N U A L “Where the world’s best athletes compete” MEDIA INFORMATION April 5, 2018 Dear Colleagues: The 60th Annual Mt. SAC Relays is set for April 19, 20 and 21, 2018 at Murdock Stadium, on the campus of El Camino College in Torrance, CA. Once again we expect over 5,000 high school, masters, community college, university and other champions from across the globe to participate. We look forward to your attendance. Due to security reasons, ALL MEDIA CREDENTIALS and Parking Permits will be held at the Credential Pick-up area in Parking Lot D, located off of Manhattan Beach Blvd. (please see attached map). Media Credentials and Parking Permit will be available for pick up on: Thursday, April 19 from 2pm - 8pm Friday, April 20 from 8am - 8pm Saturday, April 21 from 8am - 2pm Please present a photo ID to pick up your credentials and then park in lot C which is adjacent to the media credential pick up. Please remember to place your parking pass in your window prior to entering the stadium. The Mt. SAC Relays provides the following services for members of the media: Access to press box, infield and media interview area Access to copies of official results as they become available Complimentary food and beverage for all working media April 20 & 21 WiFi access Additional information including time schedules, dates, times and other important information can be accessed via our website at http://www.mtsacrelays.com If you have any additional questions or concerns, please feel free to call or e-mail me at anytime. -

Saturday Heat Sheets

Brigham Young University - Site License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 6:11 PM 4/28/2006 Page 1 2006 BYU Clarence Robison Invitational - 4/26/2006 to 4/29/2006 Clarence Robison Track, BYU, Provo, UT Meet Program - Saturday Event 9 Women Hammer Throw Saturday 4/29/2006 - 10:00 AM World Record: 249-078/29/1999 Mihaela Melinte, Romania Amer. Record: 236-037/27/2002 Anna Mahon, USA NCAA Reg: 54.15m Stadium: 234-016/25/2004 Erin Gilreath, New York Athletic Club BYU Record: 220-014/2/1998 Amy Christensen Palmer, BYU Pos NameYear School Seed Mark Flight 1 of 2 Finals 1 Jessica Lyman Fr Idaho State University 39.62m 2 Megan Butler Fr Utah Valley State College ND 3 Kelly Thompson Fr Utah Valley State College 34.06m 4 Jessica Hampton Fr University of Utah 34.08m 5 Marianne King Jr Utah Valley State College 35.73m 6 Sally Smalley Fr Weber State University 37.89m 7 Kayleen Coop Fr Utah Valley State College ND 8 Becky Phillips Fr Utah Valley State College ND Flight 2 of 2 Finals 1 Sharen Contrares Idaho State University 42.67m 2 Cali Foster Idaho State University 42.67m 3 Anna Dolegiewicz -- Unattached 62.78m 4 Vanessa Mortensen Sr University of Utah 60.84m 5 Michelle Bowen Jr Utah State University 46.02m 6 Aj Roby Sr University of Utah 47.49m 7 Candace Jones Sr Brigham Young University 45.60m 8 Aubrey Cowan Fr Brigham Young University 39.86m 9 Sarah Woydziak -- Unattached 55.00m Event 14 Men Shot Put Saturday 4/29/2006 - 10:45 AM World Record: 75-10.255/20/1990 Randy Barnes, USA Amer. -

Bob Larsen Track Meet

Finished Results - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 4:17 PM 3/29/2021 Page 1 Bob Larsen Track Meet - 3/27/2021 Finished Results UCLA Drake Stadium Results Women 100 Meter Dash ===================================================================================== Drake Stdm.: $ 10.93 1982 Evelyn Ashford, Puma Name Year School Seed Finals Wind Points ===================================================================================== Finals 1 Leger, Catherine SO Ucla 11.80 11.66 1.5 2 Miles, Kenyla SR Ucla 12.38 12.26 1.5 3 Williams, Kaitlyn FR Long Beach St. 12.19 12.27 1.5 4 Stewart, Mariah SO Cal St. Fullerton 12.55 12.81 1.5 Women 200 Meter Dash ===================================================================================== Drake Stdm.: $ 22.30 1982 Randy Givens, Florida State Name Year School Seed Finals Wind Points ===================================================================================== 1 Anderson, Shae SO Ucla 23.32 -0.3 2 Doane, Maddy SO Ucla 24.13 23.88 -0.3 3 Okoro, Chinyere FR Ucla 23.90 24.27 -0.3 4 Allain, Deja FR Cal St. Fullerton 24.90 25.96 -0.3 5 Dunbar, Toren FR Cal St. Fullerton 26.35 26.59 -0.3 6 Dahlberg, Catherine FR Cal St. Fullerton 27.48 27.45 -0.3 7 Williams, Kaitlyn FR Long Beach St. 24.81 27.63 -0.3 Women 400 Meter Dash ================================================================================ Drake Stdm.: $ 49.89 5/17/1985 Jarmila Kratochvilova, Czech Name Year School Seed Finals Points ================================================================================ 1 Anderson, Shae SO Ucla 52.18 51.84 2 Jendrezak, Kate FR Ucla 55.00 54.72 3 Krostag, Jenna FR Cal St. Fullerton 1:00.32 59.16 4 Murdica, Hailey SO Cal St. Fullerton 1:00.75 1:00.04 5 Dunbar, Toren FR Cal St. -

From the Editor

from the editor AS I SAY EVERY 8-PLUS YEARS, here at T&FN we like to think of every one of our monthly offerings as a “landmark issue,” but among the landmarkiest are the centenary issues. In the rush of the NCAA Championships last month, we had no time to mention how special the August issue was, marking as it did, edition No. 800 we’ve published since the first one rolled off the presses, dated February 1948. A trip down 7 previous Memory Lanes: ISSUE 100, MAY 1956. Back in the days when the layout was more newspaper-like, the front page featured stories on four World Records: Dave Sime with a pair of 220 straightaway marks (22.2 over the hurdles, 20.1 on the flat), Parry O’Brien with a 61-1 put and Leamon King’s 9.3 for 100y. King got a picture, as did Jim Bailey for upsetting WR holder John Landy in a 3:58.6 mile before 38,543 fans in Los Angeles. ISSUE 200, SEPTEMBER 1964. Ralph Boston made the front page for upping his 1/ own long jump WR to 27-4 4 in winning the Olympic Trials, which we somehow 1/ covered (men only) in a concise 2 2 pages. Most of the issue was dedicated to a preview of the Tokyo Games. Briton Lynn Davies, who would upset Boston and Igor Ter-Ovanesyan for the gold, was only picked for 5th place. ISSUE 300, II MAY 1971. The “Dream Mile” lived up to expectations, with Marty Liquori outdueling WR holder Jim Ryun. -

Johnson Perfect Score Masterkova Over Perec

Volume 42, No. 36 NEWSLETTER October 31, 1996 ■ MEN'SATHLETE OF THE YEAR PERFORMANCESOF THE YEAR Johnson& Masterkova JohnsonPerfect Score ScoreHere Too Men's Performance Voting: 1. Michael Johnson's 19.32, 193; 2. Daniel Komen's 7:20.67. 136; 3. Salah _.,2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Total % Hissou's 26:38.08, 80; 4. Jan Zelezny's 323·1/ 98.48, 71; 5. Donovan Bailey's 9.84, 38; 6. tie, 1. Michael Johnson ......... 39 390 100% Wilson Kipketer's 1:41 .83 & Johnson's 19.66, 21: 8. 2. Wilson Kipketer ........... - 15 10 4 4 3 3 294 75.4% tie, Allen Johnson's 12.92 al Brussels GP & Carl 3. Jan Zelezny .................. - 9 12 6 3 2 3 4 271 69.5% Lewis's 27-10 " ,/8.50 to win fourth straight Olympic LJ gold, 8; 4. Daniel Komen .............. - 12 3 7 5 6 2 2 2 259 66.4% 10. Haile Gebrselassie's 27:07.34, 4; 11. tie, 5. Allen Johnson .............. - 5 6 8 5 3 4 2 1 184 47.2% Charles Austin's 7·10/2.39, Dan O'Brien's 8824 & Lars Riede \'s 233-2/71 .06, 3; 14. lie, Kenny 3 3 2 156 40.0% 6. Frank Fredericks ......... - 2 7 6 6 6 Harrison's 59-4 ",/18.09, Michael Johnson's 43.44 7. Donovan Bailey ........... - 2 4 4 1 3 4 6 4 134 34.4% & Wilson Kipketer's 1:42.17, 2; 17. tie, Lance Deal's 6th-round 266·2/81 .12 for Olympic silver, Frank 8. -

Crystal Reports

USATF Championships Albuquerque, NM February 26‐27, 2011 Men's Long Jump Final Records World W Carl Lewis USA 8.79m 28‐10 ¼ Jan 27 1984 American A Carl Lewis Santa Monica TC 8.79m 28‐10 ¼ Jan 27 1984 Meet M Miguel Pate Alabama 8.59m 28‐2 ¼ Mar 2 2002 Sunday February 27 11:00am Top 8 advance to final Pos Athlete Name Affiliation 1 JaRod Tobler unattached 2 Tyrone Harris Shore AC 3 AAron Hill Grand Canyon Univ 4 Randall Flimmons unattached 5 Chaz Thomas unattached 6 James Douglas unattached 7 Carlton Lavong unattached 8 Jeremy Hicks unattached 9 Johnta Griffin Shore AC World Top Performances All Time World Top Performances 2011 Season 8.79m 28‐10 ¼ Carl LEWIS USA 01/27/1984 8.21m 26‐11 ¼ Louis TSATOUMAS GRE 02/19/2011 8.71m 28‐7 Sebastian BAYER GER 03/08/2009 8.17m 26‐9 ¾ Aleksandr MENKOV RUS 01/22/2011 8.62m 28‐3 ½ Iv?n PEDROSO CUB 03/07/1999 8.14m 26‐8 ½ Marquise GOODWIN USA 01/28/2011 8.60m 28‐2 ¾ Iv?n PEDROSO CUB 02/16/1997 8.13m 26‐8 ¼ Michel TORNEUS SWE 02/22/2011 8.59m 28‐2 ¼ Miguel PATE USA 03/01/2002 8.10m 26‐7 Michel TORNEUS SWE 02/15/2011 8.56m 28‐1 Carl LEWIS USA 01/16/1982 8.08m 26‐6 ¼ Wilfredo MARTINEZ CUB 01/30/2011 8.56m 28‐1 Yago LAMELA ESP 03/07/1999 8.08m 26‐6 ¼ Louis TSATOUMAS GRE 02/05/2011 8.55m 28‐0 ¾ Carl LEWIS USA 02/26/1982 8.08m 26‐6 ¼ Zedric THOMAS USA 02/11/2011 8.55m 28‐0 ¾ Carl LEWIS USA 02/11/1984 8.08m 26‐6 ¼ Eusebio CACERES ESP 02/19/2011 8.54m 28‐0 ¼ Carl LEWIS USA 01/28/1983 8.07m 26‐5 ¾ Wilfredo MARTINEZ CUB 02/22/2011 American Top Performances All Time American Top Performances 2011 Season 8.79m 28‐10