Read Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Disciples of the Buddha GREAT DISCIPLES of the BUDDHA THEIR LIVES, THEIR WORKS, THEIR LEGACY

Great Disciples of the Buddha GREAT DISCIPLES OF THE BUDDHA THEIR LIVES, THEIR WORKS, THEIR LEGACY Nyanaponika Thera and Hellmuth Hecker Edited with an Introduction by Bhikkhu Bodhi Wisdom Publications 199 Elm Street Somerville, Massachusetts 02144 USA www.wisdompubs.org © Buddhist Publication Society 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or later developed, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nyanaponika, Thera, 1901- Great disciples of the Buddha : their lives, their works, their legacy / Nyanaponika Thera and Hellmuth Hecker ; edited with an introduction by Bhikkhu Bodhi. p. cm. “In collaboration with the Buddhist Publication Society of Kandy, Sri Lanka.” Originally published: Boston, Wisdom Publications, c1997. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-86171-381-8 (alk. paper) 1. Gautama Buddha—Disciples—Biography. I. Hecker, Hellmuth. II. Bodhi, Bhikkhu. III. Title. BQ900.N93 2003 294.3’092’2—dc21 2003011831 07 06 5 4 3 2 Cover design by Gopa&Ted2, Inc. and TL Interior design by: L.J.SAWLit & Stephanie Shaiman Wisdom Publications’ books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. Printed in the United States of America This book was produced with environmental mindfulness. We have elected to print this title on 50% PCW recycled paper. As a result, we have saved the following resources: 30 trees, 21 million BTUs of energy, 2,674 lbs. -

Strong Roots Liberation Teachings of Mindfulness in North America

Strong Roots Liberation Teachings of Mindfulness in North America JAKE H. DAVIS DHAMMA DANA Publications at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies Barre, Massachusetts © 2004 by Jake H. Davis This book may be copied or reprinted in whole or in part for free distribution without permission from the publisher. Otherwise, all rights reserved. Sabbadānaṃ dhammadānaṃ jināti : The gift of Dhamma surpasses all gifts.1 Come and See! 1 Dhp.354, my trans. Table of Contents TO MY SOURCES............................................................................................................. II FOREWORD........................................................................................................................... V INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................... 1 Part One DEEP TRANSMISSION, AND OF WHAT?................................................................ 15 Defining the Topic_____________________________________17 the process of transmission across human contexts Traditions Dependently Co-Arising 22 Teaching in Context 26 Common Humanity 31 Interpreting History_____________________________________37 since the Buddha Passing Baskets Along 41 A ‘Cumulative Tradition’ 48 A ‘Skillful Approach’ 62 Trans-lation__________________________________________69 the process of interpretation and its authentic completion Imbalance 73 Reciprocity 80 To the Source 96 Part Two FROM BURMA TO BARRE........................................................................................ -

A Historical and Comparative Analysis of Renunciation and Celibacy in Indian Buddhist Monasticisms

Going Against the Grain: A Historical and Comparative Analysis of Renunciation and Celibacy in Indian Buddhist Monasticisms Phramaha Sakda Hemthep Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Master of Philosophy Cardiff School of History, Archeology and Religion Cardiff University August 2014 i Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed …………………………… (Phramaha Sakda Hemthep) Date ………31/08/2014….…… STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MPhil. Signed …………………………… (Phramaha Sakda Hemthep) Date ………31/08/2014….…… STATEMENT 2 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A Bibliography is appended. Signed …………………………… (Phramaha Sakda Hemthep) Date ………31/08/2014….…… STATEMENT 3 I confirm that the electronic copy is identical to the bound copy of the dissertation Signed …………………………… (Phramaha Sakda Hemthep) Date ………31/08/2014….…… STATEMENT 4 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed …………………………… (Phramaha Sakda Hemthep) Date ………31/08/2014….…… STATEMENT 5 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access approved by the Graduate Development Committee. Signed …………………………… (Phramaha Sakda Hemthep) Date ………31/08/2014….…… ii Acknowledgements Given the length of time it has taken me to complete this dissertation, I would like to take this opportunity to record my sense of deepest gratitude to numerous individuals and organizations who supported my study, not all of whom are mentioned here. -

Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka

Policy Studies 40 Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka Neil DeVotta East-West Center Washington East-West Center The East-West Center is an internationally recognized education and research organization established by the U.S. Congress in 1960 to strengthen understanding and relations between the United States and the countries of the Asia Pacific. Through its programs of cooperative study, training, seminars, and research, the Center works to promote a stable, peaceful, and prosperous Asia Pacific community in which the United States is a leading and valued partner. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government, private foundations, individuals, cor- porations, and a number of Asia Pacific governments. East-West Center Washington Established on September 1, 2001, the primary function of the East- West Center Washington is to further the East-West Center mission and the institutional objective of building a peaceful and prosperous Asia Pacific community through substantive programming activities focused on the themes of conflict reduction, political change in the direction of open, accountable, and participatory politics, and American under- standing of and engagement in Asia Pacific affairs. Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka Policy Studies 40 ___________ Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka ___________________________ Neil DeVotta Copyright © 2007 by the East-West Center Washington Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka By Neil DeVotta ISBN: 978-1-932728-65-1 (online version) ISSN: 1547-1330 (online version) Online at: www.eastwestcenterwashington.org/publications East-West Center Washington 1819 L Street, NW, Suite 200 Washington, D.C. -

Uposatha Sutta 18 (This Day Of) the Observance Discourse1 | a 3.70 Theme: Types of Precept Days Or Sabbaths Translated by Piya Tan ©2003

A 3.2.2.10 Aguttara Nikāya 3, Tika Nipāta 2, Dutiya Paṇṇāsaka 2, Mahā Vagga 10 (Tad-ah’) Uposatha Sutta 18 (This Day of) The Observance Discourse1 | A 3.70 Theme: Types of precept days or sabbaths Translated by Piya Tan ©2003 1 Origins of the uposatha 1.1 The ancient Indian year adopted by early Buddhism has three seasons—the cold (hem’anta), the hot (gimhāa) and the rains (vassa) (Nc 631)—each lasting about four months. Each of these seasons is further divided into 8 fortnights (pakkha) of 15 days each, except for the third and the seventh each of which has only 14 days. Within each fortnight, the full moon night and the new moon night (the four- teenth or the fifteenth) and the night of the half-moon (the eighth) are regarded as auspicious, especially the first two. For Buddhists, these are the uposatha or observance days. The observance (uposatha) was originally the Vedic upavasatha, that is, the eve of the Soma sacri- fice.2 “Soma” is the name of the brahminical moon-god to whom libation is made at the Vedic sacrifice.3 The word upavasatha comes from upavasati, “he observes; he prepares,” derived from upa- (at, near) + √VAS, “to live, dwell”; as such, upavasati literally means “he dwells near,” that is, spends the time close to a spiritual teacher for religious instructions and observances. Apparently, in Vedic times, it was believ- ed that on the full moon (paurṇa,māsa) and new moon (darśa) days, the gods came down to dwell with (upavasati) the sacrificer. -

Observing the Eight Precepts

1 Observing the Eight Precepts Contents Contents 1 Observance of the UPOSATHA or AṬA- SIL on the POYA Day 1 Observance of AṬA-SIL or UPOSATHA in Sri Lanka today 5 Observing the Eight Precepts on the Uposatha Day 17 Replacement of the Aṭṭhanga Uposatha-sīla with the Ājīvaṭṭhamaka-sīla in the Western World a Colossal Blunder 22 Ājīvaṭṭhamaka Sīla - 1st Reference in DA.I. 314 ff. Mahāli Sutta [DN. I. 150-8] 23 These BIG BLUNDERS about ATA-SIL or UPOSATHA in Sri Lanka 24 Observance ofofof thethethe UPOSATHA ororor AAAṬAAṬAṬAṬA---- SIL on the POYA Day [Anguttara Nikaya Vol. IIV.V. p. 248 ff. & p. 259 ff. UposathaUposatha Vagga ] Translated by Bhikkhu Professor Dhammavihari XLI O monks, the observance of the uposatha, adhering to the eightfold precepts, is highly rewarding, splendid and magnificent [mahapphalo hoti mahānisaṃso mahājutiko mahāvipphāro AN. IV. 248]. How does one live this eightfold uposatha to be so wonderfully effective? Herein O monks, a noble disciple thinks thus: The arahants live all their life abandoning destruction of life, refraining from killing, laying aside all weapons of 2 destruction. They are endowed with a sense of shame for doing evil, very benevolent and full of love and compassion for all living beings. On this day, during the day and during the night [imaimaññññ ca rattirattiṃṃṃṃ imaimaññññ ca divasadivasaṃṃṃṃ], I shall abandon destruction of life, refrain from killing, laying aside all weapons of destruction. I shall be endowed with a sense of shame for doing evil, shall be benevolent and full of love and compassion for all living beings. -

Exposition of the Sutra of Brahma S

11 COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM 11 BRAHMA EXPOSITION OF THE SUTRA 梵網經古迹記梵網經古迹記 EXPOSITION OF EXPOSITION OF S NET THETHE SUTRASUTRA OF OF BRAHMABRAHMASS NET NET A. CHARLES MULLER A. COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM VOLUME 11 梵網經古迹記 EXPOSITION OF THE SUTRA OF BRAHMAS NET Collected Works of Korean Buddhism, Vol. 11 Exposition of the Sutra of Brahma’s Net Edited and Translated by A. Charles Muller Published by the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism Distributed by the Compilation Committee of Korean Buddhist Thought 45 Gyeonji-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul, 110-170, Korea / T. 82-2-725-0364 / F. 82-2-725-0365 First printed on June 25, 2012 Designed by ahn graphics ltd. Printed by Chun-il Munhwasa, Paju, Korea © 2012 by the Compilation Committee of Korean Buddhist Thought, Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism This project has been supported by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, Republic of Korea. ISBN: 978-89-94117-14-0 ISBN: 978-89-94117-17-1 (Set) Printed in Korea COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM VOLUME 11 梵網經古迹記 EXPOSITION OF THE SUTRA OF BRAHMAS NET TRANSLATED BY A. CHARLES MULLER i Preface to The Collected Works of Korean Buddhism At the start of the twenty-first century, humanity looked with hope on the dawning of a new millennium. A decade later, however, the global village still faces the continued reality of suffering, whether it is the slaughter of innocents in politically volatile regions, the ongoing economic crisis that currently roils the world financial system, or repeated natural disasters. Buddhism has always taught that the world is inherently unstable and its teachings are rooted in the perception of the three marks that govern all conditioned existence: impermanence, suffering, and non-self. -

The Ceremony of Confession of Buddhism: a Study Based on the Records in the Book of a Record of the Inner Law Sent Home from the South Seas 《南海寄歸內法傳》

The Ceremony of Confession of Buddhism: A Study Based on the Records in the book of A Record of the Inner Law Sent Home from the South Seas 《南海寄歸內法傳》 Zhang Jingting, Phramaha Anon Ānando, Asst. Prof. Dr. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lawrence Y.K. LAU Guizhou Normal University, China Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] Abstract A Record of the Inner Law Sent Home from the South Seas was written by Yijing an eminent monk who lived in Chinese Tang dynasty including forty chapters about Buddhist Sangha life in the seventh century in the region of India and Malay Archipelago. Such as Vassa, the ceremony of chanting, the ordination and so on. The ceremony of confession is one of the chapters of this book. In this chapter, Yijing introduced the ceremony of two kinds of confessions, including the time, regulations, procedure of confession. This study aims at providing an overview of the ceremony of confession the Buddhist Vinaya life based on the records of the ceremony of confession in A Record of the Inner Law Sent Home from the South Seas《南海寄歸內法傳》of Yijing and the related records in Buddhist Vinayapiṭaka. The results shown that there are different records on the time of Pavarana in different school’s Vinaya, but all of them are depend on the time of the Summer-Retreat. Yijing’s records on the ceremony of Uposatha are corresponded with the records in Pāli Vinaya. The advantages of the confession to Buddhism has been discussed as well. Keywords: Confession, Buddhism, A Record of the Inner Law Sent Home from the South Seas《南海寄歸內法傳》 JIABU | Vol. -

A Study of Some Jain Responses to Non-Jain Religious Practices, by Phyllis Granoff 1 2

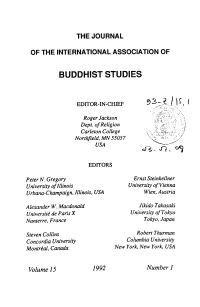

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES EDITOR-IN-CHIEF 93-^.M Roger Jackson Dept. of Religion Carleton College Northfield, MN 55057 V''-, W=:- ..- '• / USA cT£ . O"". °^ EDITORS Peter N. Gregory Ernst Steinkellner University of Illinois University of Vienna Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, USA Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki University de Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo, Japan Steven Collins Robert Thurman Concordia University Columbia University Montreal, Canada New York, New York, USA Volume 15 1992 Number 1 CONTENTS L ARTICLES 1. The Violence of Non-Violence: A Study of Some Jain Responses to Non-Jain Religious Practices, by Phyllis Granoff 1 2. Is the Dharma-kaya the Real "Phantom Body" of the Buddha?, by Paul Harrison 44 3. Lost in China, Found in Tibet: How Wonch'uk Became the Author of the Great Chinese Commentary, by John Powers 95 U. PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS Some Observations on the Present and Future of Buddhist Studies, by D. Seyfort Ruegg 104 HL AN EXCHANGE The Theatre of Objectivity: Comments on Jose Cabezon's Interpretations of mKhas grub rje's and C.W. Huntington, Jr.'s Interpretations of the TibetaV Translation of a Seventh Century Indian Buddhist Text, by C W. Huntington, Jr. 118 On Retreating to Method and Other Postmodern Turns: A Response to C. W. Huntington, Jr., by Jos6 Ignacio Cabezdn 134 IV. BOOK REVIEWS 1. Choix de Documents tibttains conserve's d la Bibliotheque Nationale compliti par quelques manuscrits de I'India Office et du British Museum, by Yoshiro Imaeda and Tsugohito Takeuchi (Alexander W. Macdonald) 144 2. -

The Emotionology of Anger in Early Buddhist Literature: Through the Lens of a Gāndhārī Verse Text Michael Butcher a Disser

The Emotionology of Anger in Early Buddhist Literature: Through the Lens of a Gāndhārī Verse Text Michael Butcher A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2020 Reading Committee: Richard Salomon, Chair Collett Cox Prem Pahlajrai Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2020 Michael Butcher University of Washington Abstract The Emotionology of Anger in Early Buddhist Literature: Through the Lens of a Gāndhārī Verse Text Michael Butcher Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Richard Salomon Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the early Buddhist attitude toward anger (G kros̱ a, OIA krodha) through the lens of an unpublished verse text, hereafter referred to as the *Kros̱ a-gas̱ a, from a newly discovered collection of Buddhist texts in the Gāndhārī language and Kharoṣṭhī script. At the microscopic level I offer an edition, translation, metrical analysis, and textual notes of the manuscript with chapters on the text’s morphology, orthography, paleography, meter, and phonology, using the format and conventions of the Gandhāran Buddhist Texts series. At the telescopic level I rely on the notion of emotionology to study the collective emotional attitudes toward anger found within early Buddhist literature by looking at key passages within the *Kros̱ a-gas̱ a in comparison with canonical texts. These passages betray the attitudes that argued for and maintained the appropriate expression of anger and the ways in which those responsible for producing and circulating such texts encouraged their understanding of and viewpoint toward this emotion. One such passage stresses the social isolation that comes from lashing out at people in anger. -

Buddhism and Women-The Dhamma Has No Gender Chand R

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 18 Issue 1 Empowering Future Generations of Women and Girls: Empowering Humanity: Select Proceedings from Article 17 the Second World Conference on Women’s Studies, Colombo, Sri Lanka Nov-2016 Buddhism and Women-The Dhamma Has No Gender Chand R. Sirimanne Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Sirimanne, Chand R. (2016). Buddhism and Women-The Dhamma Has No Gender. Journal of International Women's Studies, 18(1), 273-292. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol18/iss1/17 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2016 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Buddhism and Women–The Dhamma Has No Gender By Chand R. Sirimanne1 Abstract The increasing influence and relevance of Buddhism in a global society have given rise to a vibrant and evolving movement, particularly in the West, loosely called Socially Engaged Buddhism. Today many look to Buddhism for an answer to one of the most crucial issues of all time–eradicating discrimination against women. There is general agreement that Buddhism does not have a reformist agenda or an explicit feminist theory. This paper explores this issue from a Theravāda Buddhist perspective using the scriptures as well as recent work by Western scholars conceding that there are deep seated patriarchal and even misogynistic elements reflected in the ambivalence towards women in the Pāli Canon and bias in the socio-cultural and institutionalized practices that persist to date in Theravāda Buddhist countries. -

Request for Eight Precepts Homage to the Buddha Taking Three Refuges

Request for Eight Precepts Ahaṁ bhante, tisaraṇena saha, aṭṭhaṅga-samannāgataṁ uposatha-sīlaṁ, dhammaṁ yācāmi, anuggahaṁ katvā sīlaṁ detha, me bhante. Venerable sir, I would like to request the uposatha eight precepts with refuge in the Triple Gem. Please kindly grant me the request. Sayadaw says (S): Yam ahaṁ vadāmi, taṁ vadetha - Repeat after me. Yogis reply (Y): Āma bhante - Yes, Venerable sir. Homage to the Buddha Namo tassa bhagavato arahato sammāsambuddhasa (3 times) Homage to him, the Exalted One, the fully Enlightened One Taking Three Refuges Buddhaṁ saranaṁ gacchāmi - I go to the Buddha as my refuge. Dhammaṁ saranaṁ gacchāmi - I go to the Dhamma as my refuge. Saṁghaṁ saranaṁ gacchāmi - I go to the Sangha as my refuge Dutiyampi Buddhaṁ saranaṁ gacchāmi. For the second time, I go to the Buddha as my refuge Dutiyampi Dhammaṁ saranaṁ gacchāmi. For the second time, I go to the Dhamma as my refuge. Dutiyampi Saṁghaṁ saranaṁ gacchāmi. For the second time, I go to the Sangha as my refuge. Tatiyampi Buddhaṁ saranaṁ gacchāmi. For the third time, I go to the Buddha as my refuge. Tatiyampi Dhammaṁ saranaṁ gacchāmi. For the third time, I go to the Dhamma as my refuge. Tatiyampi Saṁghaṁ saranaṁ gacchāmi. For the third time, I go to the Sangha as my refuge. (S): Saraṇagamanaṁ paripuṇṇaṁ - Taking refuge is complete. (Y): Āma Bhante - Yes, Venerable Sir Taking Eight Preceps 1. Pāṇātipātā veramaṇi-sikkhāpadaṁ samādiyāmi. I undertake the rule of training to refrain from killing any beings. 2. Adinnādānā veramaṇi-sikkhāpadaṁ samādiyāmi. I undertake the rule of training to refrain from taking what is not given.