Been to Previous Sounds, with Top-Heavy Managerial Teams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ept, Cat Hid the Ke C Sucked, On

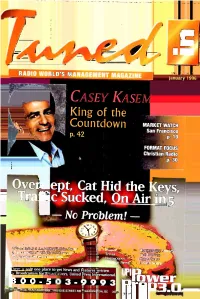

january 1996 LA94 \Y IKASEIV King of the Countdown MARKET WATCH San Francisco p. 42 PI, 10 FORMAT FOCUS Christian Radio p. 30 ept, Cat Hid the Ke cSucked, On Air No Problem! • se ing anew standard prep packages with PowerPr The industry's best value with-. Iãé to get News and Fleatures Written adcasters, United Press Iniernational. 0 3 - Ç 9 19 3 HEXIXIVARTERS 1400 EYE STREET NW 1WASHIN irO N,DC DIGILINK Hard Disk Digital Audio Workstations Audio Digital Studio Consoles Workstations Furniture Trestandout #1 leader in reliable, #1 in digital workstation sales, With over 1,000 studios in the field, high performance, digital ready Arrakis has over 1,600 Arrakis is #1 in studio furniture consoles for radio, Arrakis has workstations in use around the sales for radio. several console lines to meet your world. Using only the finest every application. The 1200 series As a multipupose digital materials, balanced laminated is ideal for compact installations. audio record-play workstation for panels, and solid oak trim, Arrakis The modular 12,000 series is radio, it replaces cart machines, furniture systems are rugged and available in 8, 18, & 28 channel reel machines, cassette recorders, attractive for years of hard use. mainframes. The 22000 Gemini & often even consoles. Digilink Available in two basic series features optional video has proven to be ideal for live on product families with literally monitors and switchers for digital air, production, news, and thousands of variations, an Arrakis workstation control. automation applications. Place a studio furniture package can easily workstation in each studio and be configured to meet your 1200 Series Consoles then interconnect them with a specific requirement, whether it is digital network for transfenng simply off the shelf or fully custom. -

Gregg Potter

Gregg Potter Emmy-Award winning drummer Gregg Potter is the drummer with the new Buddy Rich Band, a 16- piece big band of Buddy alumni who played with Buddy Rich himself! Gregg fronted The BR Band throughout the Buddy Rich Centennial Celebration Year 2017-2018 World Tour. The tour included a crisscrossing of the United States as well as a barnstorming of Europe. The European stint included a sold out week of shows at the prestigious Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club in London, where Buddy recorded several albums and solidified his drumming mastery abroad! Gregg was most recently featured in the August 2018 issue of Drumhead Magazine, the number one drum magazine in circulation. He was also featured in the December 2012 special commemorative Buddy Rich issue of Modern Drummer Magazine and the Drumhead Magazine 2017 legend’s issue. In 2016, Hal Leonard Publishing released a first-ever Buddy Rich Play Along CD/book package featuring Gregg's drumming along with the Buddy Rich Alumni Band. Gregg will front the legendary band in 2019 as they again headline shows around the world. Gregg began his professional career after winning the Slingerland/Louie Bellson National Drum Contest at the legendary Frank’s Drum Shop in Chicago. As a high school student he was presented with the Louis Armstrong Jazz Award along with several other jazz soloist individual awards. While still a teenager, he landed the drumming spot with Radio Hall of Fame icon Steve Dahl. Along with Dahl and his band Teenage Radiation, Gregg scored two hit singles, performed on Dahl’s daily radio show, syndicated national shows, Emmy-Award winning television specials, feature film soundtracks, daily morning television shows and live concert appearances. -

A World of Opportunity How Five Bulldogs Went Abroad and Discovered New Versions of Themselves OCH TAMALE MAGAZINE VOL

FALL 2019 | VOLUME 95 | ISSUE 3 News for Alumni & Friends of the University of Redlands A world of opportunity How five Bulldogs went abroad and discovered new versions of themselves OCH TAMALE MAGAZINE VOL. 95, ISSUE 3 FALL 2019 President Ralph W. Kuncl Cover Story Interim Chief Communications Officer and Editor Mika Elizabeth Ono Managing Editor Lilledeshan Bose Vice President, Advancement Tamara Michel Josserand Director, Alumni and Community Relations Shelli Stockton Director of Advancement Communications and Donor Relations Laura Gallardo ’03 Class Notes Editor Mary Littlejohn ’03 Director, Creative Services Jennifer Alvarado Graphic Designer 20 Juan Garcia Contributors A world of opportunity Steve Carroll Bea Crespo How five Bulldogs went abroad and discovered new Michelle Dang ’14 Jennifer M. Dobbs ’17 versions of themselves. Lori Ferguson Cali Godley Giulia Marchi Coco McKown ’04, ’10 Laurie McLaughlin Michele Nielsen ’99 Katie Olson Larry Pickard Carlos Puma Rachel Roche ’02 Emily Tucker William Vasta 11 Och Tamale is published by the University of Redlands. Still fine-tuning WILLIAM VASTA his lessons POSTMASTER: Professor Art Svenson receives a prestigious national Send address changes to: distinguished teaching award. Och Tamale University of Redlands PO Box 3080 Redlands, CA 92373-0999 Copyright 2019 Phone: 909-748-8070 Email: [email protected] Web: www.redlands.edu/OchTamale Cover photo by Cali Godley Please send comments and address changes to [email protected]. Please also let us know if you are 17 receiving multiple copies or would WILLIAM VASTA like to opt out of your subscription. Global horizons An interview with Steve Wuhs, assistant provost for internationalization. -

1982-07-17 Kerrville Folk Festival and JJW Birthday Bash Page 48

BB049GREENLYMONT3O MARLk3 MONTY GREENLY 0 3 I! uc Y NEWSPAPER 374 0 E: L. M LONG RE ACH CA 9 0807 ewh m $3 A Billboard PublicationDilisoar The International Newsweekly Of Music & Home Entertainment July 17, 1982 (U.S.) AFTER `GOOD' JUNE AC Formats Hurting On AM Dial Holiday Sales Give Latest Arbitron Ratings Underscore FM Penetration By DOUGLAS E. HALL Billboard in the analysis of Arbitron AM cannot get off the ground, stuck o Retailers A Boost data, characterizes KXOK as "being with a 1.1, down from 1.6 in the win- in ter and 1.3 a year ago. ABC has suc- By IRV LICHTMAN NEW YORK -Adult contempo- battered" by its FM competitors formats are becoming as vul- AC. He notes that with each passing cessfully propped up its adult con- NEW YORK -Retailers were while prerecorded cassettes contin- rary on the AM dial as were top book, the age point at which listen - temporary WLS -AM by giving the generally encouraged by July 4 ued to gain a greater share of sales, nerable the same waveband a ership breaks from AM to FM is ris- FM like call letters and simulcasting weekend business, many declaring it according to dealers surveyed. 40 stations on few years ago, judging by the latest ing. As this once hit stations with the maximum the FCC allows. The maintained an upward sales trend Business was up a modest 2% or spring Arbitrons for Chicago, De- teen listeners, it's now hurting those result: WLS -AM is up to 4.8 from evident over the past month or so. -

2008-2009 Emmy Nominations

2008-2009 Emmy Nominations Chicago/Midwest Chapter National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Tabulated by: Baker Tilly Virchow Krause, LLP 205 North Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60601 1 Category #1 Outstanding Achievement within a Regularly Scheduled News Program – Spot Coverage & Breaking News (Award to the Team of Reporters, Producers, Videographers, Editors, Directors, and Assignment Editors) • SportsNite VanLier/Kerr Passing: Lissa Christman, Charlie Schumacher, Kevin Cross, Executive Producers; Bill Koplos, Willie Parker, Producers; Tim Folke, Assignment Manager; Joe Collins, Assignment Editor; Luke Stuckmeyer, Gail Fischer, Chuck Garfien, Reporters; Eric Peterson, Director; Jared Storck, Associate Producer; Todd Williams, Videographer. Comcast SportsNet Chicago • The Historic Inauguration of President Barack Obama: Cheryl Burton, Charles Thomas, Andy Shaw, Reporters; Jason Knowles, Doug Whitmire, Derrick Robinson, Richard Hillengas, Jim Mastri, Producers. WLS • Spring Washout: Lori Waldon, Executive Producer; Jessica Schmid, Eric Marshall, Producers; Terry Sater, Kathy Mykleby, Toya Washington, Mark Baden, Reporters. WISN • Drew Peterson Arrested: Jennifer Lay-Riske, Producer; Joe Kolina, Executive Producer; Bob Sirott, Allison Rosati, Marion Brooks, Lauren Jiggetts, Anthony Ponce, Phil Rogers, Alex Perez, Reporters; Patrick Lake, Director; Stephanie Streff, Anita Selvaggio, Assignment Editors. WMAQ Category #2-a. Outstanding Achievement within a Regularly Scheduled News Program – Single Investigative Report (Award to the Reporter/Producer) • Illegal Gambling: Aaron Diamant, Reporter; Stephanie Graham, Maureen Mack, Ira Klusendorf, Joe Eufemi, Paul Marble, Justin Tiedemann, Producers. WTMJ • Property Taxes: Marsha Bartel, Chuck Quinzio, Lou Hinkhouse, Producers; Dane Placko, Reporter. WFLD • Murder or Suicide?: Dan Schwab, Lou Hinkhouse, Dartise Johnson, Producers; Jeff Goldblatt, Reporter. WFLD • Highway Workers: Marsha Bartel, Chris Willadsen, Lou Hinkhouse, Producers; Dane Placko, Reporter. -

Extensions of Remarks E237 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

February 26, 1998 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E237 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS AFFORDABLE HOUSING hearings, we learned that most of the build- reducing the national debt and ensuring the IMPROVEMENT ACT ingsÐan estimated 73 percentÐplaced in long-term solvency of the Social Security sys- service between 1992 and 1994 were newly tem. HON. NANCY L. JOHNSON constructed; the rest were existing and reha- After decades of deficit spending, Congress OF CONNECTICUT bilitated buildings. Many older neighborhoods and the Administration have taken the difficult steps necessary to eliminate the budget deficit IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES have extensive stocks of housing that could be rehabilitated and converted to low-income and restore overdue fiscal responsibility to the Thursday, February 26, 1998 rental use or improved for continued low-in- federal government. From an all-time high of Mrs. JOHNSON of Connecticut. Mr. Speak- come rental use. However, these projects are $290 billion just six years ago, the unified er, today the gentleman from Washington [Mr. often more expensive and more difficult to de- budget deficit is projected to be eliminated as METCALF] and I are introducing the Affordable velop. The bill would create a preference for soon as this year, with some forecasters now Housing Improvement Act, a measure that projects which contribute to ``a concerted com- predicting a growing surplus in the unified would: Increase the cap on the low-income munity revitalization plan,'' and it would require budget. housing tax credit, which has not been ad- States to include ``whether the project includes Despite this good news, we must put these justed for inflation since it was originally en- the use of existing housing as a part of a com- near-term projections in the broader context of acted in 1986; index the cap for inflation; im- munity revitalization plan'' in the selection cri- the long-term budget outlook and remember plement several administrative reforms rec- teria. -

Chicago Sun‐Times, 1994

Soothsay What? Sure Things for '95 Chicago Sun‐Times December 30, 1994 Some things everyone knows. The Oscars are March 27. "Kiss of 8. In an effort to attract a younger audience, WGN‐AM (720) the Spider Woman" is May 18. Taste of Chicago starts June 24. tries to hire Jonathon Brandmeier, Kevin Matthews or Danny And "M.A.N.T.I.S." can't last much longer. Bonaduce from WLUP‐FM (97.9). Instead, WGN settles for bringing back Eddie Schwartz. But the obvious isn't good enough for WeekendPlus. It's impossible to keep up on this town's activities and 9. No‐Zima Zones. entertainment without doing a little extrapolating. So we've gazed into the future to make some educated guesses about 10. Lili Taylor stars as a hip jazz club operator, Brad Pitt is a what to expect in the year ahead. And you ‐ lucky you ‐ get to yuppie entrepreneur out to get her evicted so he can install a read them: computer emporium, and Ethan Hawke is a community activist planting smoke bombs in "Wicker Park." The romantic comedy‐ 1. Despite an elaborate nationwide talent hunt in urban drama boasts shared music tracks by Veruca Salt and Red Red playgrounds, producers of the "Hoop Dreams" dramatic remake Meat. end up recruiting actors from Hollywood's home turf. Jaleel White will play the mercurial Arthur Agee, with Sean Nelson 11. Chamber orchestras call a one‐year moratorium on Vivaldi's ("Fresh") as hype victim William Gates. Also cast: Danny Aiello as "Four Seasons." Coach Gene Pingatore, Tommy Lee Jones as Bobby Knight, Richard Pryor as Arthur's dad, Natalie Cole and Marsha Warfield 12. -

Disco Demolition Photo Exhibit at Elmhurst Museum

Disco Demolition photo exhibit at Elmhurst museum By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Friday, July 19, 2013 Disco’s dead. Disco Demolition Night never dies. The most-publicized Bill Veeck promo- tion of all time – and the one that most riotously got away from the Baseball Barnum – is celebrated through Aug. 4 at the Elmhurst Historical Museum, 120 E. Park Ave., Elmhurst. The 1979 event featuring DJ Steve Dahl as ringmaster attracted some 70,000 fans to witness the destruction of thousands of disco records between games of a twinight doubleheader be- tween the White Sox and Detroit Ti- Sox pitcher Ross Baumgarten (left) with Steve Dahl muse Lorelei and another Disco Demolition Night par- gers at old Comiskey Park. Noted rock ticipant. Copyright Paul Natkin - Photo Reserve. photographer Paul Natkin was there as the official shooter of Dahl’s brain- storm party. His work that night, which provokes howls to this day, is part of his overall exhibit, “Shutter to Think: The Rock and Roll Lens of Paul Natkin,” on two floors of the museum, just east of downtown Elmhurst. The Disco Demolition photos, all in black and white, are actually shown in a video re- played continuously on a flat-screen TV on the second floor. The presentation came about, naturally, through a connection with Dahl, who produces his own daily podcast after his decades-long career as a shock jock on Chicago radio ebbed. “The Disco Demolition special exhibit segment to ‘Shutter to Think’ exhibit was put to- gether as an idea when Steve Dahl came through the main exhibit,” said Lance Tawzer, curator of the museum. -

In the Lawsuit

12-Person Jury FILED 12/12/2019 10:32 AM DOROTHY BROWN CIRCUIT CLERK COOK COUNTY, IL 2019CH14303 2019CH14303 FILED DATE: 12/12/2019 10:32 AM 2019CH14303 Hearing Date: 4/10/2020 9:30 AM - 9:30 AM Courtroom Number: 2402 Location: District 1 Court Cook County, IL Hearing Date: 4/10/2020 9:30 AM - 9:30 AM FILED Courtroom Number: 2402 12/12/2019 10:32 AM Location: District 1 Court DOROTHY BROWN Cook County, IL CIRCUIT CLERK IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF COOK COUNTY, ILLINOIS COOK COUNTY, IL 2019CH14303 COUNTY DEPARTMENT, CHANCERY DIVISION JAMES MACDONALD, ) ) Plaintiff, ) v. ) ) No. 2019CH14303 MATTHEW ERICH "MANCOW" MULLER, ) an individual; CUMULUS MEDIA, INC., a Delaware ) JURY DEMANDED Corporation, d/b/a WLS RADIO; and JOHN DOES 1-5. ) ) Defendants. ) COMPLAINT FOR INJUNCTION AND OTHER RELIEF Plaintiff James MacDonald, by his attorneys, Schoenberg Finkel Newman & Rosenberg, LLC, complains of defendants as follows: FILED DATE: 12/12/2019 10:32 AM 2019CH14303 General Allegations Common to All Counts A. Parties, Jurisdiction and Venue 1. Plaintiff, James MacDonald, DMin., (“Dr. MacDonald" or “MacDonald”), is a resident of Kane County, Illinois. Dr. MacDonald is the founder and former Senior Pastor of the Harvest Bible Chapel (“HBC”), which started in 1988, with 18 people, and by 2018, under MacDonald’s leadership, welcomed 13,000 people weekly among seven Chicago-area campuses. In addition to serving as HBC’s Senior Pastor, Dr. MacDonald taught bible and provided ministry as a guest pastor at prestigious evangelical places of faith and fellowship, including Camp of the Woods in Specular, New York, the Billy Graham Training Center at the Cove in Ashville, North Carolina, The Southern Baptist Convention Pastor’s Conference, and many leading churches across North America. -

1. MIKE and BILL VEECK Every Good Story Has a Point of Conflict. Steve

1. MIKE AND BILL VEECK Every good story has a point of conflict. Steve Dahl’s career ascended after Disco Demolition. Mike Veeck’s career crashed, and never really recovered. Bill Veeck, Jr. took the blame for Disco Demolition. The elder Veeck sold the White Sox two years after the event and spent the last summers of his life in the center field bleachers at Wrigley Field. Veeck died of cancer in 1986 at the age of seventy-one and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1991. The first time I came into Comiskey was the last time I felt safe in this world,” his son, Mike Veeck, said during a conversation on a rainy spring afternoon at U.S. Cellular Field in 2015. “I remember holding Dad’s hand and seeing this beautiful green diamond in the midst of all this macadam. It seemed like he knew everybody in the world. Everybody said, ‘Hi Bill!’ It was the most wonderful thing.” Mike Veeck had a promising career in Major League Baseball until the night of the promotion. “I’m the one who triggered it,” Veeck said. “My old man did what a good leader does. He took the heat. For ten years it was very painful for me. Steve Dahl’s career took off. I couldn’t get a job in baseball. I was red hot with soccer clubs because they like riots, and every radio station in the world wanted me as a promo director. I went to hang drywall in Florida. I got divorced. -

Disco Demolition’ Exhibit Blasts Into Town

CONTACT PERSON: Patrice Roche, Marketing & Communications Specialist Elmhurst History Museum (630) 833-1457 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: May 24, 2017 ‘Disco Demolition’ Exhibit Blasts into Town New exhibit at Elmhurst History Museum chronicles the Night Disco Died ELMHURST, Ill. – The date July 12, 1979 may not immediately ring a bell for every Chicagoan, but for those who spent that summer wearing black band tee shirts, listening to rock music on FM radio, and sporting long, shaggy hairstyles, it stands out as a memorable moment from the scrapbook of their young adult lives—it was the night that disco died. More than a few area residents were at Comiskey Park that night—possibly to see a baseball game—but more than likely to attend Teen Night. The event was envisioned as a hook to fill empty stadium seats in the middle of a dismal White Sox season and promote WLUP’s new deejay, Steve Dahl. Dahl was fostering an anti-disco campaign on Chicago air waves after being fired from a local radio station that switched to a disco format. Fueled by a 98 cent ticket price for fans who brought disco records to blow up between games of the doubleheader, the event quickly careened out of control after 50,000+ attendees packed the park and its environs. In the wake of the explosion, unruly fans took over the field causing baseball fans to shake their heads in dismay and the White Sox to eventually forfeit the second game to the Detroit Tigers. After the smoke cleared, it is said that disco met its demise and Disco Demolition (as it eventually became known) remains one of Chicago’s most infamous baseball history moments. -

Farm Aid 30 Concert Can Be Found in the Appendix

FARM AID 30 Communications Strategy Overview GOAL To grow a community of family farmers, activists and advocates, eater and donors who are coming together to change the food system. AUDIENCE • Now generation of eaters and farmers (young, diverse, 20 – 40 years old) • Loyal Farm Aid community of family farmers, activists and advocates, and eaters and donors • Partners and sponsors KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS (KPI) • Earned media coverage • Tweets using #fRoad2FarmAid, #farmaid30 and/or @FarmAid • Social media posts from artists attending Farm Aid 30 on Twitter, Facebook and/or Instagram • Social engagement • Audience engagement (contributions) at road2.farmaid.org • FarmAid.org website engagement (visits, pages per visit, avg. visit duration, % new visits, bounce rate) • Farm Aid 30 ticket sales SOCO MESSAGE Thanks to each one of us -- family farmers, activists and advocates, eaters and donors -- we have come together and the food system is changing. For 30 years, you have joined farm aid and taken many small actions that are making a big difference. Together, we are creating a food and farm system that is good for family farmers, good for the soil and water, good for our health and good for the country. | Farm Aid 30 2 SUMMARY OF OUTREACH ACTIVITIES • Beginning in January, the publicity team implemented a monthly outreach approach that emphasized Farm Aid’s impact. Outreach kicked off with promotion of Farm Aid’s drought training. • In February, Farm Aid engaged Willie Nelson and John Mellencamp to announce the date at the GRAMMY Foundation Gala, leveraging a high-profile event for anniversary visibility. • Farm Aid leveraged the Iowa Ag Summit in March to send a counter-message about the role of family farmers in a stronger food system.