1 CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION “The Ultimate Weakness of Violence Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implications of Obama's Second Term Analyzed Panel Explores

THE INDEPENDENT TO UNCOVER NEWSPAPER SERVING THE TRUTH NOTRE DAME AND AND REPORT SAINT Mary’s IT ACCURATELY VOLUME 46, ISSUE 52 | FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 9, 2012 | NDSMCOBSERVER.COM ELECTION 2012 Implications of Obama’s second term analyzed Experts provide Students react to insight on next election results four years with mixed feelings By KRISTEN DURBIN By ANNA BOARINI News Editor News Writer In the next four years of his Much like the rest of the presidency, Barack Obama country, the reactions of will expand on the efforts of Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s his first term in office. But he students to the outcome of wouldn’t have had the oppor- the 2012 presidential elec- tunity to do so without a broad tion spanned the political national base of support. spectrum. In terms of the immediate For Saint Mary’s senior Liz results of the election, politi- Craney, President Barack cal science professor Darren Obama’s reelection was a Davis said Obama’s mainte- positive outcome. nance of his 2008 electorate “The issues that mean the contributed to his reelection. KEVIN SONG | The Observer most to me, my views line President Barack Obama delivers his victory speech in Chicago on Tuesday night after winning a second see ELECTION PAGE 6 term in the White House. Obama said he plans to emphasize bipartisanship in Washington. see REACTION PAGE 7 Panel explores coeducation at Notre Dame By NICOLE MICHELS went down and then reality hit.” possibly assimilate women,” News Writer Sterling spoke at the Eck Hesburgh said. “I’m just delight- Visitor Center Thursday in a ed that we are a better university, “It was like running a gauntlet, panel discussion titled “Paving better Catholic university, better every single day.” the Way: Reflections on the Early modern university because we Jeanine Sterling, a 1976 alum- Years of Coeducation at Notre have women as well as men in na and member of the first fully Dame,” commemorating the the mix.” coeducated Notre Dame fresh- 40th anniversary of coeducation Dr. -

Everyteaaeir

... :. Our window 0 b HE SPORTING NEWS. filled with ir, is the way you greet a person that is well dressed. .You notice something; about him that requires special recognition, fake two men, Business Suits, 1 , ' tone seedy looking, the 0ther respectable looking-- although they wero BOWLING WRESTLING THE DIAMOND Wh born equal, yet, by reason of their appearapce you regard one as above the other. Good clothes command respect, attracts good com- MERRILY THEY ROLL MATCH IS OFF OVER THE FENCE pany, and good company is essen tlal to success In life. $9.50. Gaines on die Woorter and Caiino Kelly and Kehoe Will Not Meet Bit of Bate Ball Talk Heard From AUeyi Uit Night Were Thursday Night-Meet- ing To All Quarters Where the last , ' Well These are the . Attended. for Game TeaAeir Night an Understanding. is Played. if lion's share Every Y You'll jet the In school makes it her business to see that the children arcrneat aird Surprises were In storo for the leid-er- s The match between John E. Kelly John H. Conway of Webster, Mass., of the lines we la tlie VTwo-Man- " tour- and Kid Kehoe wilk not take place on who has been an um come this week. cleanly dressed, because she knot's that a neat an4 clean appear- bowling just appointed you'll nament last evening at the" Wooster Thursday evening as advertised. Kelly pire In the National league, held an closed out from the ance Is very influential in form lng a boy's habits. -

Spring' Base Ball

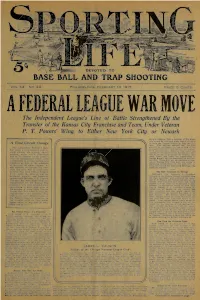

DEVOTED TO BASE BALL AND TRAP SHOOTING VOL. 64. NO. 24 PHILADELPHIA, FEBRUARY 13, 1915 PRICE 5 CENTS A FEDERAL LEAGUE WAR MOVE The Independent League's Line of Battle Strengthened By the Transfer of the Kansas City Franchise and Team, Under Veteran P. T. Powers' Wing, to Either New York City or Newark more's telegram that a meeting of the direc tors wonld be held and plans would be mads A Vital Circuit Change to force the Federal League to keep the club here. Club officials contend that the time granted by the league for the raising of the The independent Federal League necessary $100,080 fund has not yet expired. has taken a long-erpccted step to It is conceded here, however, that under the ward solving the serious circuit conditions the affairs of the Kansas City Club problem, under "^ich 1'ittaburgh will be wound up as quickly as possible. The had to be claaeit as an Eastern team, intact, and under the management of city an arrangement which made George Stovmll, will be transferred to the East ern city. Those who are stockholders at pres it impossible to arrange satisfactory ent in Kansas City Club have the option of schedules as foils to the schedules remaining stockholders in the new club or of the rii-al old major leagues. As being reimbursed for their stock koldings who was expected, the Kansas City fran make the request. chise and team will be transferred to either Xew York City or Newark, The Sale Confirmed In Chicago X. -

Theboxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 4- No 11 22 May , 2009

1 TheBoxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 4- No 11 22 May , 2009 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to sign up for the newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] The newsletter is also available as a word doc on request As always the full versions of these articles are on the website Harry Mizler Part 6 and the final installment Just before he was matched with AI Roth of New York Mizler became friendly with Betty Greenfield an attractive young woman who was to become his wife two years later. Betty met Roth at a dance and asked him during the course of conversation what he did for a living. The exchanges went something like this: Al (swelling out his chest and trying to look nonchalant "I'm a professional boxer." Betty (surprised): What a coincidence! My boy friend is a fighter—his name is Harry Mizler." Al: "Oh, that guy. I may be meeting him in the ring soon which will be tough luck for him. I’ll slaughter him." TIPPED FOR TITLE That story may carry more than one moral, but it may also have spurred Mizler to be at the peak or his form and outpoint the American by an overwhelming margin over ten rounds. Certainly Harry looked brilliant and besides being awarded a "Boxing News" Certificate of Merit was very strongly tipped to regain the British lightweight title. For the contest, made at ten stone. John Harding paid Mizler £250 and Roth £150. And to this day looks back at the promotion and considers it the best bargain he over made. -

J Eagle Brewing

I LEW M’ALLISTER, WHO HAS TWO ROUNDS WITH JOE FOGLER, WHO MEETS FAST BASE RUNNING ALEC SMITH HOLDS GIVEN BIG HELP TO TIGERS ; MORRIS HARRIS WERE GOULLET IN PURSUIT RACE MAKES GREAT TEAM, TWO-POINT LEAD ENOUGH FOR OVE Y SAYS CLARK GRIFFITH NEW YORK, Aug. 27. GRIFFITH, manager Of ttaej Harris, the Philadelphia Cincinnati Reds, declares that out CLARK OVEfl Morrisnegro heavyweight, knocked plenty of base stealing or at- MJERMOn Tom Overby, of Wilkesbarre, tempts to steal will bring a winning Pa., In the second round of a scheduled baseball team. He describes hla plana In Metropolitan Competition at ten-round bout at the National Sport- as follows: "This base running thing la Club of America last Harris bound to and Fails ing night. win, I'm going to keep* Deal, Merchantsville Boy floored Overby three times with right the boys at it while their legs are good. he to Cut Down Veteran’s Mar- swings to jaw and the last time Get the other fellows throwing and you stayed down until carried to his cor- can do a lot of tricks with them. Off gin, and Loses by T03 to 301. ner. Overby was a splendid specimen course, there are times when discre- of manhood, but his defense was crude tion must be exercised. I don’t reconi- Lad Holds Record, Though, and he never stood a chance. Harris Is mend headlong base stealing when a man but his at 71. big himself, opponent Kling or Archer Is bebhlnd, the bait. was fully three inches taller and They might get even Bescher too ofteti looked forty pounds heavier. -

Fight Record Joe Connelly (Bathgate)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Joe Connelly (Bathgate) Active: 1934-1939 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 55 contests (won: 37 lost: 13 drew: 5) Fight Record 1934 Sep 2 Joe Horridge (Rochdale) WRSF7(10) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 05/09/1934 page 10 Sep 17 Teddy Hayes (Canada) WRSF9(10) Portobello Source: Boxing Weekly Record 26/09/1934 page 15 Sep 23 Tommy Hyams (Kings Cross) LKO2(10) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 26/09/1934 page 12 Hyams boxed for the Southern Area Featherweight Title 1933 and boxed for the Southern Area Lightweight Title 1938. Sep 27 Fred Beach (Bilston) WRSF1(10) Adelphi SC, Glasgow Source: Boxing 03/10/1934 page 14 Oct 18 Nat Williams (Liverpool) WRSF6(12) Adelphi SC, Glasgow Source: Boxing 24/10/1934 page 14 Oct 21 Johnny Peters (Battersea) WKO1(10) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 24/10/1934 page 12 Nov 4 Tommy Hyams (Kings Cross) WKO7(10) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 07/11/1934 page 12 Nov 8 Young Beckett (Pentre) WPTS(12) Glasgow Source: Boxing 14/11/1934 page 14 Beckett boxed for the Welsh Flyweight Title 1929. Match made at 9st 1lb Connelly refused to weigh in and paid forfeit Nov 18 Percy Enoch (Tonyrefail) WKO2(10) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 21/11/1934 page 12 Dec 6 Tommy Hyams (Kings Cross) WKO4(12) Glasgow Source: Boxing 12/12/1934 page 16 Dec 9 Cuthbert Taylor (Merthyr) WPTS(10) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 12/12/1934 page 12 Taylor was Welsh Area Bantamweight Champion 1929. -

Boxer Died from Injuries in Fight 73 Years Ago," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 28, 2010

SURVIVOR DD/MMM /YEA RESULT RD SURVIVOR AG CITY STATE/CTY/PROV COUNTRY WEIGHT SOURCE/REMARKS CHAMPIONSHIP PRO/ TYPE WHERE CAUSALITY/LEGAL R E AMATEUR/ Richard Teeling 14-May 1725 KO Job Dixon Covent Garden (Pest London England ND London Journal, July 3, 1725; (London) Parker's Penny Post, July 14, 1725; Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org), Richard Teeling, Pro Brain injury Ring Blows: Manslaughter Fields) killing: murder, 30th June, 1725. The Proceedings of the Old Bailey Ref: t17250630-26. Covent Garden was a major entertainment district in London. Both men were hackney coachmen. Dixon and another man, John Francis, had fought six or seven minutes. Francis tired, and quit. Dixon challenged anyone else. Teeling accepted. They briefly scuffled, and then Dixon fell and did not get up. He was carried home, where he died next day.The surgeon and apothecary opined that cause of death was either skull fracture or neck fracture. Teeling was convicted of manslaughter, and sentenced to branding. (Branding was on the thumb, with an "M" for murder. The idea was that a person could receive the benefit only once. Branding took place in the courtroom, Richard Pritchard 25-Nov 1725 KO 3 William Fenwick Moorfields London England ND Londonin front of Journal, spectators. February The practice12, 1726; did (London) not end Britishuntil the Journal, early nineteenth February 12,century.) 1726; Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org), Richard Pro Brain injury Ring Misadventure Pritchard, killing: murder, 2nd March, 1726. The Proceedings of the Old Bailey Ref: t17260302-96. The men decided to settle a quarrel with a prizefight. -

International Boxing Research Organization BOX 84, GUILFORD, N.Y

International Boxing Research Organization BOX 84, GUILFORD, N.Y. 13780 Newsletter # 7 July, 1983 WELCOME IBRO welcomes new members Bruce Harris, Reg Noble, Gilbert Odd, Bob Reiss and Bob Yalen. Their addresses and description of their boxing interests appear elsewhere in this newsletter. FIRST ANNUAL JOURNAL The First Annual Journal of the International Boxing Research Organization is being distributed with this month's newsletter. Thanks very much to all the members who played a role in this publication. MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY A list of IBRO members' names and addresses appears on the last page of the Journal. Please odd Reg Noble and Bob Reiss to this list as they joined IBRO after the journal was printed. NEW ADDRESS Please note the new address for Luckett V. Davis - 552 Forest Lane. Rock Hill., SC 29730. THANKS Thanks to David Bloch, Laurence Fielding, Luckett Davis, Jack Kincaid, John Robertson and Bob Soderman for their contributions to this newsletter. Apologies to the other members who contributed material which did not make its way into this newsletter - the time factor cropping up again. The material will be used in the next issue, which hopefully, will be produced before September 1st. ELECTION OF OFFICERS A ballot for the election of officers for the 1983-84 year appears on ;:le last page of this newsletter. Dues for the 1983-84 year are also due at this time. Please mail your payment of $15 to John Grasso, Box 84, Guilford, NY 13780 along with your ballot. A LETTER Lawrence L. Roberts, No. 608, 1190 Forestwood Dr., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada L5C 1 H9, has sent the following letter to IBRO. -

Mullocks Specialist Auctioneers & Valuers

Mullocks Specialist Auctioneers & Valuers The Clive Pavilion Ludlow Racecourse Sporting & Golf Memorabilia Bromfield, Ludlow Shropshire SY8 2BT Sporting and Golf Memorabilia United Kingdom Started 05 Nov 2015 10:30 GMT Lot Description Cycle Racing programmes from 1934 to 1936 - interesting collection of Belle Vue Cycling Club racing programmes all held at Herne Hill 1 Track, all Championship or Evening meetings, plus 1950 Golden Jubilee Meeting programme, all with some writing internally and staple bleed to some, generally in G con ...[more] Cycle Racing programmes from 1934 to 1957 to incl National Cyclist Union held at Herne Hill for Annual Meeting of Champions 1934, 2 '35 and Sprint Championship and Olympic Trials '35, with some staple bleed and writing internally otherwise (G), plus 2x 1939 London cycle racing combined programmes, Oly ...[more] Cycle Racing programmes from the 1936 to 1939 - to include National Cyclists Union 24th Meeting of Champions at Herne Hill from 3 1936 to 1938 and 1945, NCU Cycling and Athletic Sports programmes at Butts Ground '36 & '39, Southern Counties Cycling Union Good Friday programme '37 (tape to spine), Open ...[more] Cycle Racing 1946/47 programmes - collection of international and club cycling programmes mostly at Herne Hill Track, including NCU 4 Challenge Meeting, National Sprint Championship and International Meeting 28th & 29th Meeting of Champions Denmark v England '47, Women's Amateur Athletic Association 1 ...[more] Large collection of Cycling racing ephemera from the 1930s onwards to incl -

Fight Record Jimmy Walsh (Chester)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Jimmy Walsh (Chester) Active: 1931-1940 Weight classes fought in: feather, light Recorded fights: 94 contests (won: 71 lost: 20 drew: 2 other: 1) Born: 1911 Died: 13th September 1964 Manager: Tony Vairo Fight Record 1931 Jan 21 Young Curley (Wrexham) WRSF5(6) Drill Hall, Wrexham Source: Wrexham and North Wales Guardian Referee: Herb Harrison Apr 6 Ossie Parry (Wrexham) WPTS(10) Drill Hall, Wrexham Source: Wrexham and North Wales Guardian Promoter: Tom Crawford Dec 2 Nat Williams (Liverpool) WRSF5(10) Drill Hall, Wrexham Source: Wrexham and North Wales Guardian Promoter: Matt Knight Dec 16 Frankie Brown (Liverpool) LPTS(10) Drill Hall, Wrexham Source: Boxing 23/12/1931 page 13 Brown boxed a British Lightweight Title Eliminator twice in 1935. Promoter: Matt Knight 1932 Jan 15 Billy Walsh (Oldham) WPTS(10) Drill Hall, Chester Source: Boxing 20/01/1932 page 12 Promoter: Matt Knight(Wrexham) Feb 6 Tom manley (Longton) WPTS(10) Whitchurch Source: Boxing 10/02/1932 page 12 Jun 15 Johnny Smith (Bootle) WRTD3(10) Drill Hall, Wrexham Source: Wrexham and North Wales Guardian Aug 10 Archie Wilkie (Gorton) WKO5(8) Winter Gardens, Morecambe Source: Boxing 17/08/1932 page 10 Aug 30 Teddy Westray (Bamber Bridge) WPTS(10) Stadium, Blackpool Source: Boxing 07/09/1932 page 11 Promoter: Jim Harris Sep 25 Joe Baldersara (Sunderland) WPTS(10) Brunswick Stadium, Leeds Source: Boxing 28/09/1932 page 10 Sep -

Theboxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 4- No 10 6TH May , 2009

1 TheBoxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 4- No 10 6TH May , 2009 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to receive future newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] The newsletter is also available as a word doc on request As always the full versions of these articles are on the website Please Help if you have any information on the following I am doing research on 2 Canadian fighters from the mid 1930's -40's . They are Sonny Jones and Katsumi Morioka . Sonny was a very good welter and Katsumi was a very good bantam . I know that they both had quite a few fights in the UK . Any info or pics would be greatly appreciated . Name: Sonny Jones Career Record: click Birth Name: Jordan Jones Nationality: Canadian Birthplace: Edmonton, AB Hometown: Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Born: 1915-03-16 Died: 1944-08-28 Age at Death: 29 According to the Jan. 4, 1946 TACOMA NEWS TRIBUNE, Jones was killed in action in France during World War II serving in the Canadian Army. Name: Katsumi Morioka Career Record: click Alias: Jimmy Morioka Birth Name: Katsumi James Inomata Nationality: Canadian Birthplace: New Westminister, BC Hometown: Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Born: 1915-09-11 Height: 5' 5½″ 2 Last year Volume 3- No 7 12th Nov , 2008 I published the first 2 installments of this 6 partstory but was unable to present the complete story as I did not have the third in the series. However this has been resolved thanks to a member of the Mizler family who have been kind enough to provide it, along with many other items, so we can continue to enjoy his career story. -

Fight Record Dave Crowley

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Dave Crowley (Clerkenwell) Active: 1929-1946 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 185 contests (won: 131 lost: 42 drew: 11 other: 1) Fight Record 1929 Aug 25 George Crain (Kings Cross) DRAW(6) Collins Music Hall, Islington Source: Boxing 28/08/1929 pages 131 and 130 Sep 2 George Green (Blackfriars) WPTS(6) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 04/09/1929 page 148 Sep 16 Tommy Cann (Notting Hill) WPTS(6) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 18/09/1929 page 181 Sep 30 Alf Patten (Canning Town) WPTS(6) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 02/10/1929 page 213 Oct 20 George Green (Blackfriars) DRAW(6) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 23/10/1929 page 258 Oct 23 Arthur Everitt (Marylebone) WPTS(6) Baths, Paddington Source: Boxing 30/10/1929 page 274 Nov 11 Jimmy Mellish WPTS(6) Baths, Fulham Source: Boxing 13/11/1929 page 308 Nov 13 Harry Brown (Hoxton) WPTS(6) Baths, Paddington Source: Boxing 20/11/1929 pages 321 and 320 Dec 2 George Wills (Stepney) WPTS(6) Baths, Fulham Source: Boxing 04/12/1929 page 356 Dec 5 George Green (Blackfriars) WPTS(6) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 11/12/1929 page 368 Dec 9 Pat Cassidy (Dublin) DRAW(6) Baths, Fulham Source: Boxing 11/12/1929 page 373 Dec 12 Fred Davidson (Spitalfields) LRTD1(6) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 18/12/1929 page 387 1930 Jan 9 Young Siki (Stepney) WPTS(6) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 15/01/1930 pages 451