1 Handout to Accompany K. Brad Ott's November 18, 2014 APHA IHRC Presentation PRESENTER's NOTE: Perhaps Because of the Need

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Year in Review TABLE of CONTENTS

2012 2012 A YEAR IN REVIEW TABLE OF CONTENTS MISSION STATEMENT/ BoaRD OF DIRECtoRS & StaFF ....... 1 LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN ............................................. 2 LETTER FROM THE FOUNDER ............................................... 3 WHO WE ARE ........................................................................ 4 REPORTING .......................................................................... 6 CHARTER SCHOOL REPORTING CORPS ................................ 8 LAND USE ............................................................................ 9 GOVERNMENT & POLITICS ................................................... 10 CRiminal JUSTICE ............................................................... 11 EDUCation .......................................................................... 12 ENVIRONMENT ..................................................................... 13 INVESTIGations .................................................................. 14 OUR PaRTNERS / OUR AWARDS ........................................... 15 OUR DONORS AND INDIVIDual SUPPORT ............................ 16 FOUNDation SUPPORT ........................................................ 18 MENTIONS IN PUBLICATIONS ............................................... 19 The Lens WHat PEOPLE ARE SAYING .................................................. 20 1025 S. Jefferson Davis Pkwy. New Orleans, LA 70125 2012 BY THE NUMBERS ....................................................... 22 (504) 483-1811 [email protected] | TheLensNola.org -

Standard 8 Professional and Public Service

Standard 8 Professional And Public Service Highlights Consistent with Loyola’s mission and commitment to service, the school is a vibrant entity for professional and public service. Since 1996, the Shawn M. Donnelley Center for Nonprofit Communications has been housed in the school and has helped more than 350 nonprofits in the New Orleans area. It is a world-class center equipped with a dozen laptop computers and excellent workspace to offer workshops to nonprofits in the area. For more than 35 years, the school has hosted the Tom Bell Silver Scribe High School Journalism Contest that brings about 50 high school students to campus each year. The school is home to the Lens, New Orleans’ award winning online investigative unit. The school has hosted three weeklong strategic communications training workshops for the federal government since 2010. LOYOLA UNIVERSITY NEW ORLEANS SELF STUDY 2013 210 1. Summarize the professional and public service activities undertaken by the unit. Include operation of campus media if under control of the unit; short courses, continuing education, institutes, high school and college press meetings; judging of contests; sponsorship of speakers addressing communication issues of public consequence and concern; and similar activities. Consistent with Loyola University New Orleans’ mission and commitment to service, the School of Mass Communication is a vibrant entity for professional and public service activities. Here are leading examples from local, state and national levels: • The school is home to The Lens (www.thelensnola.org), New Orleans’ only online nonprofit investigative journalism unit. Since 2012, the school provides office space for award winning journalists, two of whom are Loyola University journalism graduates including Edward R. -

UPTOWN CAMPUS LARGE GROUP WALKING TOUR Hello, and Welcome to Tulane University! This Is an Abridged Tour Script Written Specifically for Large Groups Visiting Campus

UPTOWN CAMPUS LARGE GROUP WALKING TOUR Hello, and welcome to Tulane University! This is an abridged tour script written specifically for large groups visiting campus. Please begin your tour at Gibson Hall (#1), the location of the Office of Undergraduate Admission. This tour will end at the Lavin-Bernick Center for University Life, or LBC (#29). Throughout your tour, you’ll find building names followed by numbers which correspond to those on our campus map. Enjoy your visit! History and Makeup of Tulane University Tulane was founded in 1834 as the Medical College of Louisiana in an effort to address the recent epidemics of Yellow Fever. In 1884, New Jersey merchant Paul Tulane donated over $1 million to endow a university “for the promotion and encouragement of intellectual, moral and industrial education.” He had made his fortune in New Orleans, and his gift expressed his appreciation for the city. Paul Tulane’s donation established the Tulane Educational Fund, which today has grown to more than $1 billion. Subsequently, the Medical College of Louisiana changed its name to the Tulane University of Louisiana. Tulane University is now comprised of 10 schools, most of which are on the Uptown Campus, with the exception of the School of Medicine, the School of Public Health & Tropical Medicine, and the School of Social Work, which are located downtown at Tulane’s original campus in the New Orleans BioDistrict. Tulane undergraduates – while all members of Newcomb-Tulane Undergraduate College – study across 5 schools: Architecture, Business, Liberal Arts, Public Health, and Science & Engineering. As you walk through campus, you’ll find a mix of both old and new buildings. -

Pontchartrain Park • Commentary from Cynthia Hedge Morrell • Louisiana’S Only Cooperative Grocery • Trumpet Award Nominations • Food Security and Sustainability

Take Me! FREE The rumpet September/OctoberT 2012 • Community Voices Orchestrating Change • Issue 6 Volume 5 INSIDE • A Revitalized Pontchartrain Park • Commentary from Cynthia Hedge Morrell • Louisiana’s Only Cooperative Grocery • Trumpet Award Nominations • Food Security and Sustainability NEIGHBORHOOD SPOTLIGHT pontchartrain Park Neighborhoods Partnership Network’s (NPN) mission is to improve our quality of life by engaging New Orleanians in neighborhood revitalization and civic process. THE TRUMPET | SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER | 2012 1 Letter From NEIGHBORHOODS PARTNERSHIP NETWORK The Executive Director The Trumpet Contents Photo: Kevin Griffin/2Kphoto The Twins — Sustainability 5 New Orleans News Survey and Democracy 7 NPN provides an inclusive and collaborative 7 NOLA Wise Makes New Orleans We’re It was the best of times, it was the worst of city-wide framework to empower Homes Energy Efficient NOLA Wise, times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of neighborhood groups in New Orleans. are you? foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the 9 Longue Vue’s Model of Sustainability epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it Find Out More at NPNnola.com was the season of darkness, it was the spring of 13 Pontchartrain Park Re-Born hope, it was the winter of despair... 19 A Commentary from Cynthia Hedge Morrell ---- Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities English novelist (1812 - 1870) NPN Board Members 21 Nola Food Co-op: 100% Owned by the 99% The end of summer in New Orleans is always the best and the worst of times for me. -

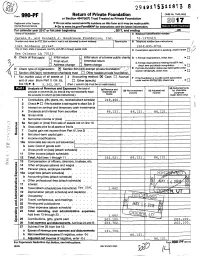

F 9^^ P^ Return of Private Foundation

294911 5311913 8 Farm 9^^_P^ Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation 2017 if' Department of the Treasury 10, Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Internal Revenue Service Do- Go to www.1rs. ov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest Information. For calendar year 2017 or tax year beginning , 2017, and ending 20 Name of foundation A Employer Identification number Carole B. and Kenneth J. Boudreaux Fo undation, Inc. 72-1372415 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 1424 Bordeaux Street ( 504 ) 895-8741 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code q C If exemption application is pending, check here ► New Orleans LA 70115 q G Check all that apply: q Initial return q Initial return of a former public charity n 1. Foreign organizations, check here ► q Final return q Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, El Address change9e [I Name change q 3 check here and attach computation • ► H Check type of organization: ® Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation`s f E If private foundation status was terminated under section 507(b)(1 )(A), check here . q q Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust q Other taxable private foundation, ► q Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method: ® Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination q end of year (from Part II, col. -

Return of Private Foundation

OMB No 1 545-0052 Form 990 -PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation 2015 ► Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. DternanReven eeServ^ce ► Information about Form 990-PF and Its separate Instructions is at www. irs.gov/form990pf. For calendar year 2015, or tax year beginning , 2015 , and ending , Name of foundation A Employer Identification number Carn1 m Pt and Kannath T P.rri rP-AiiY Fniinrlat- i nn Tnr 79-1'17741 c Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 1424 Bordeaux Street ( 504 ) 895-8741 City or town, state or province , country, and ZIP or foreign postal code q New Orleans LA 70115 C If exemption application Is pending, check here. ► G Check all that apply Initial return Initial return of a former public chanty q D I Foreign organizations, check here . ► Final return Amended return Address change Name change 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check q here and attach computation . ► H Check type of organization M Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation E If pnvate foundation status was terminated q under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here . I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: }{ Cash Accrual ► (from Part ll, column (c), line 16) q Other (specify) F If the foundation Is in a 60-month termination (Part column (d) must be on cash basis) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here . -

VHF-UHF Digest

The Magazine for TV and FM DXers September 2015 “Obviously, this station is run by WTFDA members.” - Karl Zuk (Picture from the Student Center at the University of Delaware) A WEAK JULY LEADS TO UNEXPECTED SKIP IN AUGUST MEXICO CONSIDERS ADDING NEW FMs TO MAJOR CITIES DXERS MAKE THEIR LAST CATCHES OF MEXICAN LOW-BAND TVs The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association METEOR SHOWERS INSIDE THIS VUD CLICK TO NAVIGATE Orionids 02 The Mailbox 25 Coast to Coast TV DX OCT 4 - NOV 14 05 TV News 37 Northern FM DX 10 FM News 58 Southern FM DX Leonids 22 Photo News 68 DX Bulletin Board NOVEMBER 5 - 30 THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, GREG CONIGLIO, KEITH McGINNIS AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Ryan Grabow Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org Webmaster: Tim McVey Forum Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, Bill Hale, John Zondlo and Mike Bugaj Website: www.wtfda.org; Forums: http://forums.wtfda.org September 2015 By now you have probably noticed something familiar in the new column header. It’s back. The graphics have been a little updated but it’s still the same old Mailbox, but it’s also Page Two. -

M Is S Is S I P P I R I V E R New Orleans

EAST QUADRANGLE NEW ORLEANS 5 LOUISIANA 0 5 STATE OF LOUISIANA E SERIES (TOPOGRAPHIC) 0 T 0 INU 7.5 M 0 0 5 0 90°0'0"W 5 3,6955,617 789000 0 0 788000 3,685,617 90°2'30"W 78 787000 ION AND DEVELOPMENT 78 60000 30°0'0"N T 0 DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTA 3,675,617 784000 5000 R 11 E R 12 E 5 Mile 10 78 A 90°5'0"W 0 78 0 3000 0 E 0 78 200 L 5 3,665,617 78 1000 V 0000 V 40 15 77 A 9000 39 90°7 '30"W 778000 P. A. 38 A 5 40 41 t Canal V R 100 tle 157 R 16 16 ulf Ou -5 IR E r-G -5 P 165 e -5 99 i Riv 0°0'0"N 0 G Capdau T S pp 3 0 A 0 sissi Y L D P 77 s A OL I S i K ST L Radio T 1 Mile 3 M RW 0 R l l E O AT V 98 a 301 B 1 School A AL W 9 I 64 n T L a S U S L A 15 n N Tow 20 a CO H -4 V er A Lakeview n C R B T 5 D o O I IN i 16 A 0 S t 0 H t Y a e S V M l A D Schoo ta A t 17 l L u I S E GOLF COU C r W N RSE E S 5 O E o A R LEV I l f E l T l p E 33 22000 R 90 3021 s u T 5 10 E Pan-American a Dilla G A W rd R n - f r 10 E Popp D t a e W 5 A Interchang 0 r iv L 3322000 e V u V Stadium T Henders A Carver on H 10 P R A L University L i Interchange 1A E Memori T al 5 97 O X P p B Edward S 231 L E G. -

The Young and the Settled

GENTRY, A DIFFERENT HE LOVES THEM, TRANSPLANTS KIND OF WILL YEAH, YEAH, & NEWBIES A year later, Devon YEAH Supernatives embrace Walker returns to Bruce Spizer knows New Orleans. campus. all about the Beatles. THE MAGAZINE OF TULANE UNIVERSITY TUlaneDECEMBER 2013 The Young and the Settled PAULA BURCH-CELENTANO RARE BIRDS Teresa Cole, professor and chair of the Newcomb Art Department and Ellsworth Woodward Professor of Art, looks on as her printmaking students Ben Fox-McCord (left), Zoe Corbett (center) and Imen Djouini (right) lean in to get a closer look at a John James Audubon print titled “Yellow-billed Cuckoo.” The artwork is a page from the first of four volumes produced by Audubon between 1827 and 1838. Three of those volumes reside in the Rare Books unit of Special Collections in the Howard- Tilton Memorial Library. Taking It to the Streets On the cover: The Red Beans and Rice parade, established in 2010, in the Faubourg Marigny. Photo by Cheryl Gerber. TULANE MAGAZINE DECEMBER 2013 1 PRESIDENT’S LETTER Stretch yourself academically and socially, get out of your comfort zone, and develop in- terests and skills you never thought possible. Science majors, take a course on Shakespeare. Business majors, take a course on Aristotle. English majors, take a finance course. Pre-med students, take a theater course. Theater ma- jors, take an engineering class. Environmental science majors, take a dance course. In fact, everyone should learn how to dance. It just makes you happy. Attend at least one game every semester in every sport played here at Tulane. Our athletes are first and foremost students just like you and they need and deserve your support. -

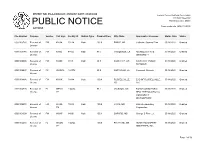

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-2-200520-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 05/20/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000100760 Renewal of FM KHGA 78214 Main 103.9 EARLE, AR Catherine Joanna Flinn 05/18/2020 Granted License 0000103746 Renewal of FM KNSU 48825 Main 91.5 THIBODAUX, LA NICHOLLS STATE 05/18/2020 Granted License UNIVERSITY 0000100008 Renewal of FM KVMN 9418 Main 89.9 CAVE CITY, AR CAVE CITY PUBLIC 05/18/2020 Granted License SCHOOLS 0000100597 Renewal of FX W230CL 142778 93.9 GARYVILLE, LA Covenant Network 05/18/2020 Granted License 0000104886 Renewal of FM KWKK 31884 Main 100.9 RUSSELLVILLE, EAB OF RUSSELLVILLE, 05/18/2020 Granted License AR LLC 0000104705 Renewal of FL WFNH- 194484 95.1 JACKSON, MS FOCUS ON NATURAL 05/18/2020 Granted License LP HEALTH EDUCATION & COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT 0000100570 Renewal of FM WJXN- 72818 Main 100.9 UTICA, MS Flinn Broadcasting 05/18/2020 Granted License FM Corporation 0000101008 Renewal of FM WOXF 84091 Main 105.1 OXFORD, MS George S Flinn , Jr . 05/18/2020 Granted License 0000102238 Renewal of FL WAON- 194824 100.5 PICAYUNE, MS HERITAGE BAPTIST 05/18/2020 Granted License LP MINISTRIES, INC. Page 1 of 56 REPORT NO. PN-2-200520-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 05/20/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. -

Introducing New Orleans

© Lonely Planet Publications INTRODUCING NEW ORLEANS The Preservation Hall Jazz Band performs traditional jazz (p181) The difference between you and this city is that you have an internal ‘no.’ ‘Yeah, you right.’ Those three words are practically the motto of this city; a nonstop affirmation, an unceasing encouragement to have another – bite to eat, coffee, whiskey, whatever. For a city so proud of taking it easy, the pace of life here is maddening. But for all that reveling in…well…revelry, this city isn’t a shallow hedonist. New Orleans embraces the spiritual, the cerebral and the shadows, those sources of her fabled arts and music. Here, they recognize la beaute d’entropie: the Beauty of Decay. Unlike so much of the USA, the Crescent City doesn’t operate in terms clean, preprocessed or safely packaged. New Orleans understands that gothic edges make Mardi Gras beads flash brighter, and that the flickering flames of Garden District gas lamps shine better in the dark. Remember the three ‘I’s. The first two, Indulgence and Immersion, are easy to pick up on. It’s brown sugar on bacon instead of oatmeal for breakfast; a double served neat instead of light beer; sex in the morning instead of being early for work (‘My streetcar was down.’). But the biggest ‘I’ here is Intermixing. Tolerating everything and learning from it is the soul of this city. Social tensions and divisions of race and income keep New Orleans jittery, but when its citizens aspire to that great Creole ideal – a mix of all influences creating something better – we get all sorts of things. -

List of Radio Stations in Louisiana

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia List of radio stations in Louisiana From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page The following is a list of Federal Communications Commission–licensed radio stations in the Contents American state of Louisiana, which can be sorted by their call signs, frequencies, cities of license, Featured content licensees, and programming formats. Current events Random article Contents [hide] Donate to Wikipedia 1 List of radio stations Wikipedia store 2 Defunct 3 See also Interaction 4 References Help 5 Bibliography About Wikipedia Community portal 6 External links Recent changes 7 Images Contact page Tools List of radio stations [edit] What links here This list is complete and up to date as of March 1, 2019. Related changes Upload file Call City of Special pages Frequency Licensee[2][3] Format sign license[1][2] open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com sign license[1][2] Permanent link Page information Spotlight Broadcasting of KAGY 1510 AM Port Sulphur Americana Wikidata item New Orleans, LLC Cite this page KAJD- 96.5 FM Baton Rouge City of Joy, Inc. Urban Gospel Print/export LP Create a book KAJN- 102.9 FM Crowley Agape Broadcasters, Inc. Contemporary Christian Download as PDF FM Printable version Coastal Broadcasting of KANE 1240 AM New Iberia Americana In other projects Lafourche, L.L.C. Wikimedia Commons KAOK 1400 AM Lake Charles Cumulus Licensing LLC News/Talk Languages KAPB- Bontemps Media Services 97.7 FM Marksville Classic country Add links FM LLC American Family KAPI 88.3 FM Ruston Inspirational (AFR) Association American Family KAPM 91.7 FM Alexandria Inspirational (AFR) Association KASO 1240 AM Minden Minden Broadcasting, LLC Classic hits American Family KAVK 89.3 FM Many Inspirational (AFR) Association American Family KAXV 91.9 FM Bastrop Inspirational (AFR) Association KAYT 88.1 FM Jena Black Media Works, Inc.