Bendell, James Alexander (#207)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada and the BATTLE of VIMY RIDGE 9-12 April 1917 Bataille De Vimy-E.Qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 4

BRERETON GREENHOUS STEPHEN J. HARRIS JEAN MARTIN Bataille de Vimy-E.qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 2 Bataille de Vimy-E.qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 1 Bataille de Vimy-E.qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 3 BRERETON GREENHOUS STEPHEN J. HARRIS JEAN MARTIN Canada and the BATTLE OF VIMY RIDGE 9-12 April 1917 Bataille de Vimy-E.qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 4 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Greenhous, Brereton, 1929- Stephen J. Harris, 1948- Canada and the Battle of Vimy Ridge, 9-12 April 1917 Issued also in French under title: Le Canada et la Bataille de Vimy 9-12 avril 1917. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-660-16883-9 DSS cat. no. D2-90/1992E-1 2nd ed. 2007 1.Vimy Ridge, Battle of, 1917. 2.World War, 1914-1918 — Campaigns — France. 3. Canada. Canadian Army — History — World War, 1914-1918. 4.World War, 1914-1918 — Canada. I. Harris, Stephen John. II. Canada. Dept. of National Defence. Directorate of History. III. Title. IV.Title: Canada and the Battle of Vimy Ridge, 9-12 April 1917. D545.V5G73 1997 940.4’31 C97-980068-4 Cet ouvrage a été publié simultanément en français sous le titre de : Le Canada et la Bataille de Vimy, 9-12 avril 1917 ISBN 0-660-93654-2 Project Coordinator: Serge Bernier Reproduced by Directorate of History and Heritage, National Defence Headquarters Jacket: Drawing by Stéphane Geoffrion from a painting by Kenneth Forbes, 1892-1980 Canadian Artillery in Action Original Design and Production Art Global 384 Laurier Ave.West Montréal, Québec Canada H2V 2K7 Printed and bound in Canada All rights reserved. -

Recensement De La Population

Recensement de la population Populations légales en vigueur à compter du 1er janvier 2015 Arrondissements - cantons - communes 62 PAS-DE-CALAIS Recensement de la population Populations légales en vigueur à compter du 1er janvier 2015 Arrondissements - cantons - communes 62 - PAS-DE-CALAIS RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE SOMMAIRE Ministère de l'Économie et des Finances Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques Introduction.....................................................................................................62-V 18, boulevard Adolphe Pinard 75675 Paris cedex 14 Tél. : 01 41 17 50 50 Tableau 1 - Population des arrondissements et des cantons........................ 62-1 Directeur de la publication Jean-Luc Tavernier Tableau 2 - Population des communes..........................................................62-4 INSEE - décembre 2014 INTRODUCTION 1. Liste des tableaux figurant dans ce fascicule Tableau 1 - Populations des arrondissements et des cantons Tableau 2 - Populations des communes, classées par ordre alphabétique 2. Définition des catégories de la population1 Le décret n° 2003-485 du 5 juin 2003 fixe les catégories de population et leur composition. La population municipale comprend les personnes ayant leur résidence habituelle sur le territoire de la commune, dans un logement ou une communauté, les personnes détenues dans les établissements pénitentiaires de la commune, les personnes sans abri recensées sur le territoire de la commune et les personnes résidant habituellement dans une habitation mobile recensées -

Liste Des Communes Situées Sur Une Zone À Enjeu Eau Potable

Liste des communes situées sur une zone à enjeu eau potable Enjeu eau Nom commune Code INSEE potable ABANCOURT 59001 Oui ABBEVILLE 80001 Oui ABLAINCOURT-PRESSOIR 80002 Non ABLAIN-SAINT-NAZAIRE 62001 Oui ABLAINZEVELLE 62002 Non ABSCON 59002 Oui ACHEUX-EN-AMIENOIS 80003 Non ACHEUX-EN-VIMEU 80004 Non ACHEVILLE 62003 Oui ACHICOURT 62004 Oui ACHIET-LE-GRAND 62005 Non ACHIET-LE-PETIT 62006 Non ACQ 62007 Non ACQUIN-WESTBECOURT 62008 Oui ADINFER 62009 Oui AFFRINGUES 62010 Non AGENVILLE 80005 Non AGENVILLERS 80006 Non AGNEZ-LES-DUISANS 62011 Oui AGNIERES 62012 Non AGNY 62013 Oui AIBES 59003 Oui AILLY-LE-HAUT-CLOCHER 80009 Oui AILLY-SUR-NOYE 80010 Non AILLY-SUR-SOMME 80011 Oui AIRAINES 80013 Non AIRE-SUR-LA-LYS 62014 Oui AIRON-NOTRE-DAME 62015 Oui AIRON-SAINT-VAAST 62016 Oui AISONVILLE-ET-BERNOVILLE 02006 Non AIX 59004 Non AIX-EN-ERGNY 62017 Non AIX-EN-ISSART 62018 Non AIX-NOULETTE 62019 Oui AIZECOURT-LE-BAS 80014 Non AIZECOURT-LE-HAUT 80015 Non ALBERT 80016 Non ALEMBON 62020 Oui ALETTE 62021 Non ALINCTHUN 62022 Oui ALLAINES 80017 Non ALLENAY 80018 Non Page 1/59 Liste des communes situées sur une zone à enjeu eau potable Enjeu eau Nom commune Code INSEE potable ALLENNES-LES-MARAIS 59005 Oui ALLERY 80019 Non ALLONVILLE 80020 Non ALLOUAGNE 62023 Oui ALQUINES 62024 Non AMBLETEUSE 62025 Oui AMBRICOURT 62026 Non AMBRINES 62027 Non AMES 62028 Oui AMETTES 62029 Non AMFROIPRET 59006 Non AMIENS 80021 Oui AMPLIER 62030 Oui AMY 60011 Oui ANDAINVILLE 80022 Non ANDECHY 80023 Oui ANDRES 62031 Oui ANGRES 62032 Oui ANHIERS 59007 Non ANICHE 59008 Oui ANNAY 62033 -

Calendrier De Collecte Cambligneul

Janvier Février Mars Avril Mai Juin L 1 Nouvel an J 1 J 1 D 1 M 1 Fête du travail V 1 M 2 V 2 V 2 L 2 L. de Pâques M 2 S 2 M 3 S 3 S 3 M 3 J 3 D 3 Calendrier de collecte J 4 D 4 D 4 M 4 V 4 L 4 2018 V 5 L 5 L 5 J 5 S 5 M 5 S 6 M 6 M 6 V 6 D 6 M 6 Cambligneul D 7 M 7 M 7 S 7 L 7 J 7 L 8 J 8 J 8 D 8 M 8 Victoire 1945 V 8 M 9 V 9 V 9 L 9 M 9 S 9 Chers habitants, EDITO M 10 S 10 S 10 M 10 J 10 Ascension D 10 Voici l’édition 2018 de votre calendrier de collecte qui, en J 11 D 11 D 11 M 11 V 11 L 11 plus de reprendre vos jours V 12 L 12 L 12 J 12 S 12 M 12 de ramassage, vous donne S 13 M 13 M 13 V 13 D 13 M 13 de l’information afin de vous D 14 M 14 M 14 S 14 L 14 J 14 guider dans votre geste de tri au quotidien. Ensemble, L 15 J 15 J 15 D 15 M 15 V 15 poursuivons nos efforts en matière de recy- M 16 V 16 V 16 L 16 D. Pâques M 16 S 16 clage, de valorisation et de réduction de nos M 17 S 17 S 17 M 17 L. -

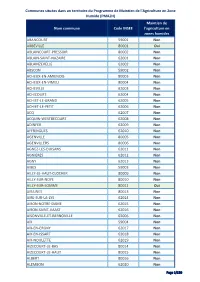

(PMAZH) Nom Commune Code INSEE

Communes situées dans un territoire du Programme de Maintien de l'Agriculture en Zone Humide (PMAZH) Maintien de Nom commune Code INSEE l'agriculture en zones humides ABANCOURT 59001 Non ABBEVILLE 80001 Oui ABLAINCOURT-PRESSOIR 80002 Non ABLAIN-SAINT-NAZAIRE 62001 Non ABLAINZEVELLE 62002 Non ABSCON 59002 Non ACHEUX-EN-AMIENOIS 80003 Non ACHEUX-EN-VIMEU 80004 Non ACHEVILLE 62003 Non ACHICOURT 62004 Non ACHIET-LE-GRAND 62005 Non ACHIET-LE-PETIT 62006 Non ACQ 62007 Non ACQUIN-WESTBECOURT 62008 Non ADINFER 62009 Non AFFRINGUES 62010 Non AGENVILLE 80005 Non AGENVILLERS 80006 Non AGNEZ-LES-DUISANS 62011 Non AGNIERES 62012 Non AGNY 62013 Non AIBES 59003 Non AILLY-LE-HAUT-CLOCHER 80009 Non AILLY-SUR-NOYE 80010 Non AILLY-SUR-SOMME 80011 Oui AIRAINES 80013 Non AIRE-SUR-LA-LYS 62014 Non AIRON-NOTRE-DAME 62015 Non AIRON-SAINT-VAAST 62016 Non AISONVILLE-ET-BERNOVILLE 02006 Non AIX 59004 Non AIX-EN-ERGNY 62017 Non AIX-EN-ISSART 62018 Non AIX-NOULETTE 62019 Non AIZECOURT-LE-BAS 80014 Non AIZECOURT-LE-HAUT 80015 Non ALBERT 80016 Non ALEMBON 62020 Non Page 1/130 Communes situées dans un territoire du Programme de Maintien de l'Agriculture en Zone Humide (PMAZH) Maintien de Nom commune Code INSEE l'agriculture en zones humides ALETTE 62021 Non ALINCTHUN 62022 Non ALLAINES 80017 Non ALLENAY 80018 Non ALLENNES-LES-MARAIS 59005 Non ALLERY 80019 Non ALLONVILLE 80020 Non ALLOUAGNE 62023 Non ALQUINES 62024 Non AMBLETEUSE 62025 Oui AMBRICOURT 62026 Non AMBRINES 62027 Non AMES 62028 Non AMETTES 62029 Non AMFROIPRET 59006 Non AMIENS 80021 Oui AMPLIER 62030 Non AMY -

Dossiers De Personnel Des Instituteurs

ARCHIVES DEPARTEMENTALES DU PAS-DE-CALAIS DOSSIERS DE PERSONNEL DES INSTITUTEURS Arras-Dainville 1 INTRODUCTION Les dossiers de personnel des instituteurs ont fait l’objet de plusieurs versements qui n’ont pas tous été décrits avec le même degré de précision et qui se chevauchent chronologiquement. Le chercheur consultera : - les dossiers classés en série T1 qui ont fait l’objet d’un index patronymique et géographique par Thérèse Louage2 et Jean-Yves Léopold en 1995. Les instituteurs dont les dossiers sont conservés dans cette série ont exercé durant la période 1878- 1945 ; - le versement 1304 W qui contient les dossiers des instituteurs nés entre 1842 et 1916 ; le répertoire est constitué d’un index patronymique ; - les cotes 1 W 58001-62365 (passim)3 qui constituent les dossiers des instituteurs nés entre 1889 et 1939 ; le répertoire est constitué d’un index patronymique ; - le versement 6 W dont le répertoire manque de précision : indication des noms extrêmes du dossier uniquement et pas d’indication de date ; un sondage rapide permet toutefois d’affirmer que cette série paraît la plus récente et recouvre peu ou prou des années de naissance entre 1910 et 1960. Composition-type d’un dossier : - fiche individuelle de renseignements : elle indique l’état civil du postulant à l’enseignement, ses diplômes et une appréciation de l’inspecteur primaire sur ses aptitudes décelées lors d’un entretien préalable ; - rapports semestriels puis annuels du directeur sur son adjoint : y sont décrites non seulement ses qualités professionnelles, mais aussi sa conduite en dehors de l’école ; - rapports de l’inspecteur primaire ; - lettres de félicitation ou de blâme adressées par l’inspecteur d’académie ; - lettres de plainte contre l’instituteur transmises à l’inspecteur primaire ; - demandes de changement de poste : elles sont accompagnées des arrêtés de nomination. -

Région Territoire De Vie-Santé Commune Code Département Code

Code Code Région Territoire de vie-santé Commune département commune Hauts-de-France Chauny Abbécourt 02 02001 Hauts-de-France Tergnier Achery 02 02002 Hauts-de-France Soissons Acy 02 02003 Hauts-de-France Marle Agnicourt-et-Séchelles 02 02004 Hauts-de-France Tinqueux Aguilcourt 02 02005 Hauts-de-France Bohain-en-Vermandois Aisonville-et-Bernoville 02 02006 Hauts-de-France Tinqueux Aizelles 02 02007 Hauts-de-France Soissons Aizy-Jouy 02 02008 Hauts-de-France Gauchy Alaincourt 02 02009 Hauts-de-France Pinon Allemant 02 02010 Hauts-de-France Vic-sur-Aisne Ambleny 02 02011 Hauts-de-France Soissons Ambrief 02 02012 Hauts-de-France Tinqueux Amifontaine 02 02013 Hauts-de-France Tergnier Amigny-Rouy 02 02014 Hauts-de-France Villers-Cotterêts Ancienville 02 02015 Hauts-de-France Tergnier Andelain 02 02016 Hauts-de-France Tergnier Anguilcourt-le-Sart 02 02017 Hauts-de-France Pinon Anizy-le-Château 02 02018 Hauts-de-France Ham Annois 02 02019 Hauts-de-France Hirson Any-Martin-Rieux 02 02020 Hauts-de-France Hirson Archon 02 02021 Hauts-de-France Fère-en-Tardenois Arcy-Sainte-Restitue 02 02022 Hauts-de-France Fère-en-Tardenois Armentières-sur-Ourcq 02 02023 Hauts-de-France Laon Arrancy 02 02024 Hauts-de-France Gauchy Artemps 02 02025 Hauts-de-France Montmirail Artonges 02 02026 Hauts-de-France Laon Assis-sur-Serre 02 02027 Hauts-de-France Laon Athies-sous-Laon 02 02028 Hauts-de-France Saint-Quentin Attilly 02 02029 Hauts-de-France Caudry Aubencheul-aux-Bois 02 02030 Hauts-de-France Hirson Aubenton 02 02031 Hauts-de-France Ham Aubigny-aux-Kaisnes -

Délimitation Des Nouveaux Cantons Dans Le Département

27 février 2014 JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE Texte 22 sur 149 Décrets, arrêtés, circulaires TEXTES GÉNÉRAUX MINISTÈRE DE L’INTÉRIEUR Décret no 2014-233 du 24 février 2014 portant délimitation des cantons dans le département du Pas-de-Calais NOR : INTA1401219D Le Premier ministre, Sur le rapport du ministre de l’intérieur, Vu le code général des collectivités territoriales, notamment son article L. 3113-2 ; Vu le code électoral, notamment son article L. 191-1 ; Vu le décret no 2012-1479 du 27 décembre 2012 authentifiant les chiffres des populations de métropole, des départements d’outre-mer de la Guadeloupe, de la Guyane, de la Martinique et de La Réunion, de Saint- Barthélemy, de Saint-Martin et de Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, ensemble le I de l’article 71 du décret no 2013-938 du 18 octobre 2013 portant application de la loi no 2013-403 du 17 mai 2013 relative à l’élection des conseillers départementaux, des conseillers municipaux et des conseillers communautaires, et modifiant le calendrier électoral ; Vu la délibération du conseil général du Pas-de-Calais en date du 10 janvier 2014 ; Vu les autres pièces du dossier ; Le Conseil d’Etat (section de l’intérieur) entendu, Décrète : Art. 1er.−Le département du Pas-de-Calais comprend trente-neuf cantons : – canton no 1 (Aire-sur-la-Lys) ; – canton no 2 (Arras-1) ; – canton no 3 (Arras-2) ; – canton no 4 (Arras-3) ; – canton no 5 (Auchel) ; – canton no 6 (Auxi-le-Château) ; – canton no 7 (Avesnes-le-Comte) ; – canton no 8 (Avion) ; – canton no 9 (Bapaume) ; – canton no 10 (Berck) ; – canton no 11 (Béthune) ; – canton no 12 (Beuvry) ; – canton no 13 (Boulogne-sur-Mer-1) ; – canton no 14 (Boulogne-sur-Mer-2) ; – canton no 15 (Brebières) ; – canton no 16 (Bruay-la-Buissière) ; – canton no 17 (Bully-les-Mines) ; – canton no 18 (Calais-1) ; – canton no 19 (Calais-2) ; – canton no 20 (Calais-3) ; – canton no 21 (Carvin) ; – canton no 22 (Desvres) ; – canton no 23 (Douvrin) ; – canton no 24 (Etaples) ; . -

Elections Des Tribunaux Paritaires Des Baux Ruraux Liste Electorale Provisoire Des Bailleurs

ELECTIONS DES TRIBUNAUX PARITAIRES DES BAUX RURAUX LISTE ELECTORALE PROVISOIRE DES BAILLEURS NOM DE JEUNE N° NOM - NOM MARITAL PRENOMS NAISSANCE ADRESSES CP COMMUNES FILLE 1 BELLENGUEZ LEBLOND Colette 24/06/1925 14 Rue d'Agerue 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS 2 BOCQUILLON THULLIER Jacqueline 16/10/1958 6 Rue de Beauvois 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS 3 DELBE Jean Marie 07/07/1949 6 Le Rietz 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS 4 DELPORTE NANTOIS Annick 25/04/1954 17 Rue de Beauvois 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS 5 DELTOUR Henri 12/03/1932 16 le Rietz 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS 6 DELTOUR Michel 04/01/1955 6 Rue de Linzeux 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS 7 HERNU Gilbert 10/07/1930 4 Rue d'Agerue 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS 8 HOGUET Yannick 06/08/1945 2 Rue de Beauvois 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS 9 HOGUET Guy 15/07/1934 1 Rue de Guinecourt 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS 10 HOGUET Daniel 11/05/1943 Rue des Champs 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS 11 HONORE Emile 04/03/1945 5 Rue de Croisette 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS 12 LECHERF François 20/11/1927 2 Rue des Champs 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS 13 LEMOINE DELMOTTE Marie Antoinette 26/02/1931 6 Place du Quesnoy 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS 14 OUTREBON Henri 11/02/1933 14 Place du Quesnoy 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS 15 PERAL HOGUET Raymonde 17/04/1921 4 Rue de Beauvois 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS ELECTIONS DES TRIBUNAUX PARITAIRES DES BAUX RURAUX LISTE ELECTORALE PROVISOIRE DES BAILLEURS NOM DE JEUNE N° NOM - NOM MARITAL PRENOMS NAISSANCE ADRESSES CP COMMUNES FILLE 16 PHILIS RICART Josette 22/01/1936 5 Rue de Linzeux 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS 17 SCHOTTER René 14/04/1927 16 Rue de l'Eglise 62130 ŒUF EN TERNOIS 18 THULLIER CREUSET Josette -

Préfet Du Pas-De-Calais

PRÉFET DU PAS-DE-CALAIS DIRECTION DÉPARTEMENTALE DES TERRITOIRES ET DE LA MER DU PAS-DE-CALAIS Service De l’Environnement ARRÊTÉ PRÉFECTORAL MODIFIANT L’ARRÊTÉ PREFECTORAL DU 13 NOVEMBRE 2018 RELATIF A L’INFORMATION DES ACQUÉREURS ET DES LOCATAIRES DE BIENS IMMOBILIERS SOUMIS A DES RISQUES NATURELS, MINIERS ET TECHNOLOGIQUES LE PRÉFET DU PAS-DE-CALAIS Vu le code général des collectivités territoriales ; Vu le code de l’environnement, notamment les articles L. 125-5, R. 125-23 à R. 125-27 et R. 563-1 à R.563-8 ; Vu le code de la construction et de l’habitation, notamment ses articles L. 271-4 et L. 271-5 ; Vu le décret 2010-1254 du 10 octobre 2010 relatif à la prévention du risque sismique ; Vu le décret n°2004-374 du 29 avril 2004 modifié relatif aux pouvoirs des préfets, à l’organisation et à l’action des services de l’État dans les régions et les départements ; Vu le décret du 16 février 2017 portant nomination de Monsieur Fabien SUDRY, en qualité de Préfet du Pas-de-Calais (hors classe) ; Vu le décret du 5 septembre 2019 portant nomination de M. Alain CASTANIER, administrateur général détaché en qualité de Sous-Préfet hors classe, en qualité de Secrétaire Général de la préfecture du Pas-de-Calais (clase fonctionnelle II) ; Vu l'arrêté préfectoral n°2019-10-17 du 6 septembre 2019 portant délégation de signature à Monsieur Alain CASTANIER, secrétaire général de la Préfecture du Pas-de-Calais ; Vu l’arrêté ministériel du 27 juin 2018 portant délimitation des zones à potentiel radon du territoire français en application l’article L. -

La Lettre Du Et Concilier Les Différents Usages !

Le Schéma d’Aménagement et de Gestion des Eaux, ou comment protéger la vallée de la Scarpe La lettre du et concilier les différents usages ! n°1 janvier 2016 Qu'est-ce qu'un SAGE ? 1. Un outil de planification locale Edito Comment gérer durablement l’eau Au-delà des frontières administratives et des oppositions d’intérêt, le SAGE (Schéma sur notre territoire ? Comment d’Aménagement et de Gestion des Eaux) est un document stratégique de planification qui vise concilier le bon fonctionnement de à organiser une gestion globale et équilibrée de l’eau et des milieux aquatiques sur un bassin la vie aquatique, de nos usages versant. Le SAGE doit permettre la coexistence des différents usages de l’eau sur le territoire où domestiques, industriels, agricoles il s’appliquera, tout en assurant la satisfaction des besoins de tous ainsi que la pérennité et le bon ou encore de loisirs ? Comment état des ressources en eau et des milieux aquatiques. protéger nos rivières, notre environnement, et notamment Le SAGE s’articule pour cela autour de deux documents principaux : la Scarpe. Comment gérer les - le Plan d’Aménagement et de Gestion Durable (PAGD) de la ressource en eau et des milieux éventuels risques d’inondations ou aquatiques qui définit les objectifs du SAGE et évalue les moyens et les délais pour y parvenir. Le de pollutions ? Ce sont à partir de PAGD est opposable aux décisions administratives. ces questions que les élus ont décidé - le règlement qui fixe les règles de gestion, les priorités d’usage, les mesures nécessaires à la de se regrouper autour d’un outil, le SAGE, Schéma d’Aménagement et restauration et à la préservation de la qualité de l’eau, des milieux aquatiques et de la continuité de Gestion des Eaux. -

Enfance-Jeunesse Séniors Sport Culture Lecture Numérique Loisirs

C C C A CAMPAGNES DE L’ARTOIS Faitesvotre RentréeAVEC LES C AMPAGNES DE L 'A RTOIS Enfance-Jeunesse Séniors Sport Lecture Numérique Tourisme Culture Loisirs Guide des activités 2019, CAMP GNES tous les programmes sur notre site internet ! DE L’ A RTOIS Communauté de Communes WWW. CAMPAGNESARTOIS.FR Enfance-Jeunesse RELAIS ASSISTANTS MATERNELS MULTI ACCUEIL & MICRO-CRÈCHE Enfance-Jeunesse Le Relais « Ô P’tits Mômes » accueille les assistants maternels, les gardes à domicile, les parents Les établissements d’accueil, « Les Cabrioles » et « Les P’tits Écureuils », sont ouverts aux enfants employeurs et les enfants de 0 à 6 ans pour s’informer, se rencontrer, partager, participer, etc. dès 3 mois et jusque 5 ans. Ils offrent des modes de garde collectifs destinés aux familles du territoire qui permettent aux enfants d’être accueillis en journée ou pour quelques heures. Les enfants sont ANIMATIONS (de 9h30 à 11h30) accompagnés par des professionnels de la Petite-Enfance. Séniors Séniors Lundi : Avesnes-le-Comte ou Habarcq, Cambligneul ou Villers-Brûlin Des temps forts sont organisés tout au long de l’année et des partenariats permettent de diversifier Mardi : Beaufort-Blavincourt ou Izel-les-Hameau, Berles-Monchel ou Hermaville les activités (psychomotricté, contes, lecture …). Mercredi : Bienvillers-au-Bois ou Noyelle-Vion et Pas-en-Artois (1 fois sur 2) Jeudi : Aubigny-en-Artois ou Penin, Berles-au-Bois ou Gouy-en-Artois Inscription obligatoire et possibilité de mise en place d’un contrat d’accueil. Vendredi : Duisans ou Savy-Berlette Tarifs