At the Geneml Meeting of the Society, Held at Little M Issenden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buckingham Share As at 16 July 2021

Deanery Share Statement : 2021 allocation 3AM AMERSHAM 2021 Cash Recd Bal as at % Paid Share To Date 16-Jul-21 To Date A/C No Parish £ £ £ % S4642 AMERSHAM ON THE HILL 75,869 44,973 30,896 59.3 DD S4645 AMERSHAM w COLESHILL 93,366 55,344 38,022 59.3 DD S4735 BEACONSFIELD ST MARY, MICHAEL & THOMAS 244,244 144,755 99,489 59.3 DD S4936 CHALFONT ST GILES 82,674 48,998 33,676 59.3 DD S4939 CHALFONT ST PETER 88,520 52,472 36,048 59.3 DD S4971 CHENIES & LITTLE CHALFONT 73,471 43,544 29,927 59.3 DD S4974 CHESHAM BOIS 87,147 51,654 35,493 59.3 DD S5134 DENHAM 70,048 41,515 28,533 59.3 DD S5288 FLAUNDEN 20,011 11,809 8,202 59.0 DD S5324 GERRARDS CROSS & FULMER 224,363 132,995 91,368 59.3 DD S5351 GREAT CHESHAM 239,795 142,118 97,677 59.3 DD S5629 LATIMER 17,972 7,218 10,754 40.2 DD S5970 PENN 46,370 27,487 18,883 59.3 DD S5971 PENN STREET w HOLMER GREEN 70,729 41,919 28,810 59.3 DD S6086 SEER GREEN 75,518 42,680 32,838 56.5 DD S6391 TYLERS GREEN 41,428 24,561 16,867 59.3 DD S6694 AMERSHAM DEANERY 5,976 5,976 0 0.0 Deanery Totals 1,557,501 920,018 637,483 59.1 R:\Store\Finance\FINANCE\2021\Share 2021\Share 2021Bucks Share20/07/202112:20 Deanery Share Statement : 2021 allocation 3AY AYLESBURY 2021 Cash Recd Bal as at % Paid Share To Date 16-Jul-21 To Date A/C No Parish £ £ £ % S4675 ASHENDON 5,108 2,975 2,133 58.2 DD S4693 ASTON SANDFORD 6,305 6,305 0 100.0 S4698 AYLESBURY ST MARY 49,527 23,000 26,527 46.4 S4699 AYLESBURY QUARRENDON ST PETER 7,711 4,492 3,219 58.3 DD S4700 AYLESBURY BIERTON 23,305 13,575 9,730 58.2 DD S4701 AYLESBURY HULCOTT ALL SAINTS -

Records of Buckinghamshire, Or, Papers and Notes on the History

THE KHYNE TOLL OF CHETWODE. 'Ev St rw avrtZ xpovq TOVT^>9 IV T<$ MVAIY OvXifiiry <JVOQ XPWA ytverai fi(ya' opfitipLivoq Si . OVTOQ IK TOV ovpeoc TOVTOV RA TtHv Mt/crcov tpya SiaipfftlpiaKe. iroXX&KI Si oi MUCTOI iir avrov ifcXOovric, iroieeaicov fxlv ovSiv icaicov, iira<T\ov Si rrpog avrov. Herod. Clio. sect, xxxvi. As it is the province of the Society to collect notices of local customs and privileges tending to throw light upon the history of our county, I shall offer no excuse for drawing attention to the Rhyne Toll of Chetwode, an ancient and singular right exercised by Sir John Chet- wode, Bart., and his ancestors. The Rhyne commences at nine o'clock in the morning of the 30th of October, when a horn is blown on the Church-hill at Buckingham, and gingerbread and beer distributed among the assembled boys. The girls present are not admitted to a share in the bounty, but no reason has been assigned for this par- tiality save that of immemorial custom. When a suffi- cient quantity of these viands has been disposed of, the bearer of the cakes and ale proceeds through the village of Tingewick to the extreme boundary of the county towards Oxfordshire, in front of the Red Lion Inn near Finmere, three miles distant, where the horn is again sounded, and a fresh distribution of provisions takes place, also limited to the boys. At the conclusion of these formalities, the Rhyne is proclaimed to have begun. One toll-collector is stationed in the town of Buckingham, and another in the hamlet of Gawcott, a mile and a half dis- tant, each empowered to levy a tax, at the rate of two shillings a score, upon all cattle or swine, driven through the townships or hamlets of Barton, Chetwode, Tingewick, Gawcott, Hillesden, the Precint of Prebend End in Buckingham, Lenborough, and Preston-cum-Cowley, until twelve o'clock at night on the 7th day of November, when the Rhyne closes. -

Tingewick Meadows and Woodlands Local Biodiversity Opportunity Area Statement

Tingewick Meadows and Woodlands Local Biodiversity Opportunity Area Statement This map is reproduced from Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the controller of Her Majesty's Stationary Office© Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. © Copyright Buckinghamshire County Council Licence No. 100021529 2010 Area Coverage 2379ha ha Number of Local wildlife sites 7 Designated Sites SSSI 1 BAP Habitat Lowland Fen 1.5ha Lowland Meadow 12 ha Lowland Mixed Deciduous Woodland 22.5ha A lowlying undulating area on the southern flank of the Ouse Valley containing Tingewick Meadows SSSI and LWS meadows and woodlands. This BOA connects with Ouse Valley Local BOA Joint Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire Claylands, Upper Thames Clay Vales Character Area Landscape Wooded agricultural land. Types Geology Mostly mudstone, with a band of sandstone and limestone around Tingewick Topography An undulating landscape with a low ridge running east west through Tingewick and Lonborough Woods. Biodiversity Lowland Meadows – Tingewick Meadows SSSI. There are 2 LWSs in the south of the area – Field A Cowley Farm and 2 Meadows West of Chetwode/Barton Hill Woodland – There are 5 LWS Woodlands accumulated around Barton Hartshorn Hedgerows – The areas around Barton Hartshorn and west of Gawcott Tingewick Meadows and Woodlands Local Biodiversity Opportunity Area Statement June 2010 contain concentrations of pre-18th century enclosures and so may contain species rich hedgerows Ponds – There are several ponds in the area Access Woodland Trust own Round Wood LWS. There is a good network of rights of way. Archaeology There is ridge and furrow in the lower lying areas to the north and south of the ridge around Tingewick, Gawcott, Barton Hartshorn, Preston Bissett and Hilsden. -

Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Spring 2021 3-Month Construction Look Ahead Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire

Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Spring 2021 3-month construction look ahead Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Spring 2021 This forward look covers HS2 associated work in Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire. The document includes: • A forward look of construction activities planned in the next three months • Works to be aware of that will take place in the next 12 months, but may not yet have been confirmed The dates and information included in the forward look are subject to change as programme develops. These will be updated in the next edition of the forward look. If you have any queries about the information in this forward look, the HS2 Helpdesk is available all day, every day on 08081 434 434 or by emailing [email protected] Page 2 Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Contents Map 1 – Turweston to Mixbury................................................................................................ 4 Map 2 – Finmere to Twyford .................................................................................................... 6 Map 3 – Calvert ......................................................................................................................... 9 Map 4 – Quainton ................................................................................................................... 11 Map 5 – Waddesdon to Stoke Mandeville ............................................................................ 13 Map 6 – Wendover ................................................................................................................. -

Neolithic to Early Bronze Age Buckinghamshire: a Resource Assessment

Neolithic to Early Bronze Age Buckinghamshire: a resource assessment Inheritance Mobility Although Neolithic populations are thought to have had continued mobility, more and more evidence for Neolithic settlement has come to light. In Buckinghamshire the most important evidence comes from excavations in advance of the construction of Eton Rowing Course (ERC) and the Maidenhead to Windsor and Eton Flood Alleviation Scheme (MWEFAS), mainly in the parish of Dorney in South Bucks on the Thames. The evidence points to intensive use of the area by people in the Early Neolithic but it is not certain that it represents year-round sedentary occupation rather than seasonal re-use (Allen et al 2004). Other evidence does point to continued mobility, such as the artefact scatters at Scotsgrove Mill, Haddenham (Mitchell 2004) and East Street, Chesham (Collard 1990) for example, reflecting visits over a long period of time. Persistent places Mesolithic persistent places continue to have meaning for Early and later Neolithic populations. These persistent places include East Street, Chesham (Collard 1990, 18) and Late Neolithic to Early Bronze Age activity at Chessvale Bowling Club nearby (Halsted 2006, 23-8). Another persistent place seems to have been the lower reaches of the River Colne. Recent excavations at the Sanderson Site, Denham (Halsey 2005) continued the activity from nearby Three Ways Wharf, Uxbridge (Lewis 1991). Other persistent places include the attractive river valley location at Bancroft in Milton Keynes (Williams 1993, 5), and Scotsgrove Mill, Haddenham, where the River Thame meets one of its tributaries (Mitchell 2004, 1). These persistent places may have been the basis of evolving ideas about land tenure. -

Local Area Engagement Plan Buckinghamshire & Oxfordshire

1 Local Area Engagement Plan Buckinghamshire & Oxfordshire 2019 High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has been tasked by the Department for Transport (DfT) with managing the delivery of a new national high speed rail network. It is a non-departmental public body wholly owned by the DfT. High Speed Two (HS2) Limited Two Snowhill Snow Hill Queensway Birmingham B4 6GA Telephone: 08081 434 434 General email enquiries: [email protected] Website: www.hs2.org.uk High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the HS2 website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. © High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, 2019, except where otherwise stated. Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. This information is licensed under the Open Government Licence v2.0. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ version/2 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or e-mail: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Printed in Great Britain on paper containing at least 75% recycled fibre. 1 HS2 Ltd Local Area Engagement Plan: Buckinghamshire & Oxfordshire About this plan How we will engage We’re committed to being a good neighbour and we‘ll ensure that you can find out about our planned works and activities in your area easily. -

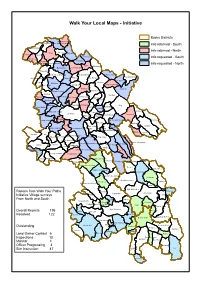

Walk Your Local Maps - Initiative

Walk Your Local Maps - Initiative Bucks Districts Lillingstone Lovell Lillingstone Dayrell with Luffield Abbey Info returned - South Biddlesden Info returned - North Stowe Akeley Leckhampstead Turweston Shalstone Beachampton Info requested - South Westbury Foscott Water Stratford Maids Moreton Thornton Radclive-cum-Chackmore Info requested - North Nash Whaddon Buckingham Thornborough Tingewick Gawcott with Lenborough Great Horwood Newton Longville Great Brickhill Barton Hartshorn Padbury Adstock Little Horwood Stoke Hammond Chetwode Mursley Hillesden Preston Bissett Addington Drayton Parslow Winslow Soulbury Steeple Claydon Swanbourne Twyford Stewkley Poundon Middle Claydon Granborough East Claydon Hoggeston Charndon Dunton Calvert Green Edgcott HogshawNorth Marston Wing Marsh Gibbon Oving Cublington Creslow Slapton Grendon Underwood Whitchurch Quainton Aston Abbotts Mentmore Pitchcott Hardwick Woodham Wingrave with Rowsham Edlesborough Ludgershall Kingswood Weedon Cheddington Westcott Quarrendon Ivinghoe Hulcott Wotton Underwood WaddesdonFleet Marston Watermead Bierton with Broughton Marsworth Pitstone Boarstall Brill Upper Winchendon Dorton Ashendon ColdharbourAylesbury Lower Winchendon BucklandDrayton Beauchamp Stone with Bishopstone and Hartwell Aston Clinton Oakley Chilton Cuddington Weston Turville Chearsley Stoke Mandeville Worminghall Dinton-with-Ford and Upton Halton Long Crendon Haddenham Ickford Shabbington Aston SandfordGreat and Little Kimble Ellesborough Kingsey Wendover Cholesbury-cum-St Leonards Longwick-cum-Ilmer The Lee Ashley Green Princes Risborough Chartridge Great and Little Hampden Chesham Great Missenden Lacey Green Latimer Bledlow-cum-Saunderton Chesham Bois Little Missenden Reports from Walk Your Paths Bradenham Chenies Hughenden Amersham Initiative Village surveys Radnage Little Chalfont From North and South Downley Hazlemere Stokenchurch West Wycombe Coleshill Piddington and Wheeler End Penn Chalfont St. Giles High Wycombe Seer Green Overall Reports 195 Ibstone Lane End Resolved 122 Turville Chepping Wycombe Chalfont St. -

BUCKINGHAMSHIRE POSSE COMITATUS 1798 the Posse Comitatus, P

THE BUCKINGHAMSHIRE POSSE COMITATUS 1798 The Posse Comitatus, p. 632 THE BUCKINGHAMSHIRE POSSE COMITATUS 1798 IAN F. W. BECKETT BUCKINGHAMSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY No. 22 MCMLXXXV Copyright ~,' 1985 by the Buckinghamshire Record Society ISBN 0 801198 18 8 This volume is dedicated to Professor A. C. Chibnall TYPESET BY QUADRASET LIMITED, MIDSOMER NORTON, BATH, AVON PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY ANTONY ROWE LIMITED, CHIPPENHAM, WILTSHIRE FOR THE BUCKINGHAMSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY CONTENTS Acknowledgments p,'lge vi Abbreviations vi Introduction vii Tables 1 Variations in the Totals for the Buckinghamshire Posse Comitatus xxi 2 Totals for Each Hundred xxi 3-26 List of Occupations or Status xxii 27 Occupational Totals xxvi 28 The 1801 Census xxvii Note on Editorial Method xxviii Glossary xxviii THE POSSE COMITATUS 1 Appendixes 1 Surviving Partial Returns for Other Counties 363 2 A Note on Local Military Records 365 Index of Names 369 Index of Places 435 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The editor gratefully acknowledges the considerable assistance of Mr Hugh Hanley and his staff at the Buckinghamshire County Record Office in the preparation of this edition of the Posse Comitatus for publication. Mr Hanley was also kind enough to make a number of valuable suggestions on the first draft of the introduction which also benefited from the ideas (albeit on their part unknowingly) of Dr J. Broad of the North East London Polytechnic and Dr D. R. Mills of the Open University whose lectures on Bucks village society at Stowe School in April 1982 proved immensely illuminating. None of the above, of course, bear any responsibility for any errors of interpretation on my part. -

Jennifer Faith Collins, Amanda Jane Sweeting and Belinda Carey Naylor

0396 IN PARLIAMENT HOUSE OF COMMONS SESSION 2013-14 HIGH SPEED RAIL (LONDON - WEST MIDLANDS) BILL PETITION Against - on Merits - Praying to be heard By Counsel. &c. To the Honourable the Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland ia Parliament assembled. THE HUMBLE PETITION of JENNIFER FAITH COLLINS, AMANDA JANE SWEETING AND BELINDA CAREY NAYLOR. SHEWEIH as foUows:- 1 A BiLL (hereinafter referred to as "the Bill") has been introduced and is now- pending in your honourable House intituled "A Bill to make provision for a railway between Euston in London and a junction with the West Coast Main Line at Handsacre in Staffordshire, with a spur from Old Oak Common in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham to a junction with the Channel Ttinnel Rail Link at York Way in the London Borough of Islington and a sptir from Water Orton in Warwickshire to Curzon Street in Birmingham; arid for connected purposes." 2 The BiU is presented by Mr Secretary McLoughlin, supported by The Prime Minister, The Deputy Prime Minister, Mr Chancellor of the Exchequer, Secretary Theresa May, Secretary Vince Cable, Secretary Iain Dimcan Smith, Secretary Eric Pickles, Secretary Owen Paterson, Secretary Edward Davey, and Mr Robert Goodwill. 3 Clauses 1 to 36 set Out the Bill's objectives in relation to the construction and operation of the railway mentioned in paragraph 1 above. They include provision for the construction of works, highways and road traffic matters, the compulsory acquisition of land and other provisions relating to the use of land, planning permission, heritage issues, trees and noise. -

MEDIEVAL PA VINGTILES in BUCKINGHAM SHIRE LTS'l's F J

99 MEDIEVAL PAVINGTILES IN BUCKINGHAM SHIRE By CHRISTOPHER HOHLE.R ( c ncluded). LT S'l'S F J ESI NS. (Where illuslratio ns of the designs were given m the last issue of the R rt•ord.t, Lit e umnlJ er o f the page where they will LJc found is give11 in tl te margi n). LIST I. TILES FROM ELSEWHERE, NOW PRESERVED IN BUCKINGHAM SHIRE S/1 Circular tile representing Duke Morgan (fragment). Shurlock no. 10. Little Kimble church. S/2 Circular tile representing Tnstan slaying Morhaut. Shurlock no. 13. Little Kimble church. S/3 Circular tile representing Tristan attacking (a dragon). Shurlock no. 17. Little Kimble church. S/4 Circular tile representing Garmon accepting the gage. Shurlock no. 21. Little Kimble church. S/5 Circular tile representing Tristan's father receiving a message. Shurlock no. 32. Little Kimble church. S/6 Border tile with grotesques. Shurlock no. 39. Little Kimble church. S/7 Border tile with inscription: + E :SAS :GOVERNAIL. Little Kimble church (fragment also from "The Vine," Little Kimble). S/8 Wall-tiles (fragmentary) representing an archbishop, a queen, S/9 and a king trampling on their foes. S/10 Shurlock frontispiece. Little Kimble church (fragment of S/10 from "The Vine"). Nos. S/1-10 all from Ohertsey Abbey, Surrey ( ?). S/11 Border tile representing a squirrel. Wilts. Arch. Mag. vol. XXXVIII. Bucks Museum, Aylesbury, as from Bletchley. No. S/11 is presumably from Malmesbury Abbey. LIST II. "LATE WESSEX" TILES in BUCKINGHAMSHIRE p. 43 W /1 The Royal. arms in a circle. Bucks. -

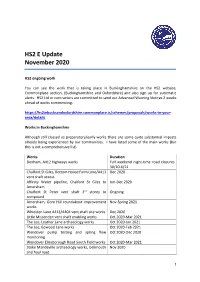

HS2 E Update November 2020

HS2 E Update November 2020 HS2 ongoing work You can see the work that is taking place in Buckinghamshire on the HS2 website, Commonplace section, (Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire) and also sign up for automatic alerts. HS2 Ltd or contractors are committed to send out Advanced Warning Notices 2 weeks ahead of works commencing: https://hs2inbucksandoxfordshire.commonplace.is/schemes/proposals/works-in-your- area/details Works in Buckinghamshire Although still classed as preparatory/early works there are some quite substantial impacts already being experienced by our communities. I have listed some of the main works (but this is not a comprehensive list) Works Duration Denham, A412 highways works Full weekend night-time road closures 30/10-6/11 Chalfont St Giles, Bottom House Farm Lane/A413 Dec 2020 vent shaft access Affinity Water pipeline, Chalfont St Giles to Jun-Dec 2020 Amersham Chalfont St Peter vent shaft 3rd storey to Ongoing compound Amersham, Gore Hill roundabout improvement Nov-Spring 2021 works Whielden Lane A413/A404 vent shaft site works Dec 2020 Little Missenden vent shaft enabling works Oct 2020-Mar 2021 The Lee, Leather Lane archaeology works Oct 2020-Jan 2021 The Lee, Bowood Lane works Oct 2020-Feb 2021 Wendover pump testing and spring flow Oct 2020-Dec 2020 monitoring Wendover Ellesborough Road South Field works Oct 2020-Mar 2021 Stoke Mandeville archaeology works, bellmouth Nov 2020 and haul road 1 Aylesbury Golf Course works Jul 2020-Apr 2021 Calvert compound works Apr 2021 Chetwode ecology and clearance works Sep-Dec 2020 Quainton construction activities Sep-Spring 2021 Waddesdon works Jul-Spring 2021 Fleet Marston trial trenching works Sep-Dec 2020 Steeple Claydon utility works Jul-Aug 2021 Turweston works Oct-Dec 2020 Twyford - Newton Purcell early works Oct-Summer 2021 What is Buckinghamshire Council doing to mitigate impacts on communities? Buckinghamshire Council remains opposed to HS2. -

Public Session

PUBLIC SESSION MINUTES OF ORAL EVIDENCE taken before HIGH SPEED RAIL COMMITTEE On the HIGH SPEED RAIL (LONDON – WEST MIDLANDS) BILL Wednesday, 21 October 2015 (Morning) In Committee Room 5 PRESENT: Mr Robert Syms (Chair) Mr Mark Hendrick Sir Peter Bottomley Mr Henry Bellingham Geoffrey Clifton-Brown Mr David Crausby _____________ IN ATTENDANCE Mr Timothy Mould QC, Counsel, Department for Transport Witnesses: Mr Andrew Boniface Mr Charlie Clare Ms Belinda Naylor Ms Natalie Merry Ms Edi Smockum Mr Joe Hodges Mr Tim Smart, International Director for High Speed Rail, CH2M Hill _____________ IN PUBLIC SESSION INDEX Subject Page Presentation by the Promoter 3 Andrew John Boniface Submissions by Mr Boniface 7 Response by Mr Mould 17 Belinda Naylor, Charlie Clare, et al. Submissions by Mr C lare 22 Evidence of Ms Merry 26 Ms Merry, cross-examined by Mr Mould 27 Further submissions by Ms C lare 28 Submissions by Ms Naylor 30 Further submissions by Ms C lare 31 Response from Mr Mould 32 Mr Smart, examined by Mr Mould 38 Mr Smart, cross-examined by Mr Mould 47 Closing submissions by Ms Clare 55 Steeple C laydon Parish Council Submissions by Ms Smockum 56 Evidence of Mr Hodges 59 Response from Mr Mould 61 2 (At 09.30) 1. CHAIR: Order, order. Welcome. Good morning to the HS2 Select Committee. Before we start on you, Mr Boniface, I think we’ll have another go with the fly-through since the Department for Transport spent a fortune on doing it. Roughly where are we now? 2. MR MOULD QC (DfT): Five minutes in.