Changing Views at Banaras Hindu University on the Academic Study of Religion: a First Report from an On‑Going Research Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Facts About Religion in India | Pew Research Center

5 facts about religion in India | Pew Research Center https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/06/29/5-facts-about-re... MAIN MORE NEWS IN THE NUMBERS JUNE 29, 2018 5 facts about religion in India BY SAMIRAH MAJUMDAR Graffiti on a Mumbai wall. (Indranil Mukherjee/AFP/Getty Images) India is home to 1.4 billion people – almost one-sixth of the world’s population – who belong to a variety of ethnicities and religions. While 94% of the world’s Hindus live in India, there also are substantial populations of Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains and adherents of folk religions. For most Indians, faith is important: In a 2015 Pew Research Center survey, eight-in-ten Indians said religion is very important in their lives. Here are five facts about religion in India: 1 1 of 7 11/4/20, 2:51 PM 5 facts about religion in India | Pew Research Center https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/06/29/5-facts-about-re... India’s massive population includes not only the vast majority of the world’s Hindus, but also the second-largest group of Muslims within a single country, behind only Indonesia. By 2050, India’s Muslim population will grow to 311 million, making it the largest Muslim population in the world, according to Pew Research Center projections. Still, Indian Muslims are projected to remain a minority in their country, making up about 18% of the total population at midcentury, while Hindus figure to remain a majority (about 77%). India is a religiously pluralistic and multiethnic democracy – the largest 2 in the world. -

Religion in Modern India • Rel 3336 • Spring 2020

RELIGION IN MODERN INDIA • REL 3336 • SPRING 2020 PROFESSOR INFORMATION Jonathan Edelmann, Ph.D., University of Florida, Department of Religion, Anderson Hall [email protected]; (352) 392-1625 Office Hours: M,W,F • 9:30-10:30 AM or by appointment COURSE INFORMATION Course Meeting Time: Spring 2020 • M,W,F • Period 5, 11:45 AM - 12:35 PM • Matherly 119 Course Qualifications: 3 Credit Hours • Humanities (H), International (N), Writing (WR) 4000 Course Description: The modern period typically covers the years 1550 to 1850 AD. This course covers religion in India since the beginning of the Mughal empire in the mid-sixteenth century, to the formation of the independent and democratic Indian nation in 1947. The concentration of this course is on aesthetics and poetics, and their intersection with religion; philosophies about the nature of god and self in metaphysics or ontology; doctrines about non-dualism and the nature of religious experience; theories of interpretation and religious pluralism; and concepts of science and politics, and their intersection with religion. The modern period in India is defined by a diversity of religious thinkers. This course examines thinkers who represent the native traditions like Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism, as well as the ancient and classical traditions in philosophy and literature that influenced native religions in the modern period. Islam and Christianity began to interact with native Indian religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism during the modern period. Furthermore, Western philosophies, political theories, and sciences were also introduced during India’s modern period. The readings in this course focus on primary texts and secondary sources that critically portray and engage this complex and rich history of India’s modern period. -

Conflict Between Freedom of Expression and Religion in India—A Case Study

Article Conflict between Freedom of Expression and Religion in India—A Case Study Amit Singh Centre for Social Studies, University of Coimbra, Colégio de S. Jerónimo Apartado 3087, 3000-995 Coimbra, Portugal; [email protected] Received: 24 March 2018; Accepted: 27 June 2018; Published: 29 June 2018 Abstract: The tussle between freedom of expression and religious intolerance is intensely manifested in Indian society where the State, through censoring of books, movies and other forms of critical expression, victimizes writers, film directors, and academics in order to appease Hindu religious-nationalist and Muslim fundamentalist groups. Against this background, this study explores some of the perceptions of Hindu and Muslim graduate students on the conflict between freedom of expression and religious intolerance in India. Conceptually, the author approaches the tussle between freedom of expression and religion by applying a contextual approach of secular- multiculturalism. This study applies qualitative research methods; specifically in-depth interviews, desk research, and narrative analysis. The findings of this study help demonstrate how to manage conflict between freedom of expression and religion in Indian society, while exploring concepts of Western secularism and the need to contextualize the right to freedom of expression. Keywords: freedom of expression; Hindu-Muslim; religious-intolerance; secularism; India 1. Background Ancient India is known for its skepticism towards religion and its toleration to opposing views (Sen 2005; Upadhyaya 2009), However, the alarming rise of Hindu religious nationalism and Islamic fundamentalism, and consequently, increasing conflict between freedom of expression and religion, have been well noted by both academic (Thapar 2015) and public intellectuals (Sorabjee 2018; Dhavan 2008). -

State and Religion in India: the Indian Secular Model1

Erik Reenberg Sand STATE AND RELIGION IN INDIA: THE INDIAN SECULAR MODEL1 Abstract This article attempts to characterize the so-called Indian secular model by examining the relation- ship between the state and religion as ratified by the Indian Constitution of 1950. It is shown how, in spite of the ideal of separating state and religion, the state in several cases was allowed to inter- vene in the affairs of religion. Thus, although the constitution allows individuals free choice of religion and religious denominations the right to establish and administer religious and educa- tional institutions, it also allows the state various means of interfering in religious matters. A major reason for this is the responsibility of the state to protect the rights of the various under- privileged groups in Indian society. The last part of the paper deals briefly with the growing cri- tique of the secular system and ideology from the side of Hindu nationalists and Indian intellec- tuals, a critique which is largely based on misuses of the system by the Indian political elites. Key words: India, religion, state, constitutionalism The overall aim of the present article is to offer a brief characterization of the so-called Indian secular model by examining the relationship between the state and religion as ratified by the Indian Constitution of 1950. In addition to this, the paper will deal briefly with an area where religious group practices still seem to resist secularization, namely the practice of personal laws, as well as with the growing critique of the secular system and ideology from the side of Hindu nationalists and Indian intellectuals. -

Cultural Dynamics

Cultural Dynamics http://cdy.sagepub.com/ Authoring (in)Authenticity, Regulating Religious Tolerance: The Implications of Anti-Conversion Legislation for Indian Secularism Jennifer Coleman Cultural Dynamics 2008 20: 245 DOI: 10.1177/0921374008096311 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cdy.sagepub.com/content/20/3/245 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Cultural Dynamics can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cdy.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cdy.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://cdy.sagepub.com/content/20/3/245.refs.html >> Version of Record - Oct 21, 2008 What is This? Downloaded from cdy.sagepub.com at The University of Melbourne Libraries on April 11, 2014 AUTHORING (IN)AUTHENTICITY, REGULATING RELIGIOUS TOLERANCE The Implications of Anti-Conversion Legislation for Indian Secularism JENNIFER COLEMAN University of Pennsylvania ABSTRACT This article explores the politicization of ‘conversion’ discourses in contemporary India, focusing on the rising popularity of anti-conversion legislation at the individual state level. While ‘Freedom of Religion’ bills contend to represent the power of the Hindu nationalist cause, these pieces of legislation refl ect both the political mobility of Hindutva as a symbolic discourse and the prac- tical limits of its enforcement value within Indian law. This resurgence, how- ever, highlights the enduring nature of questions regarding the quality of ‘conversion’ as a ‘right’ of individuals and communities, as well as reigniting the ongoing battle over the line between ‘conversion’ and ‘propagation’. Ul- timately, I argue that, while the politics of conversion continue to represent a decisive point of reference in debates over the quality and substance of reli- gious freedom as a discernible right of Indian democracy and citizenship, the widespread negative consequences of this legislation’s enforcement remain to be seen. -

Freedom of Religion and the Indian Supreme Court: The

FREEDOM OF RELIGION AND THE INDIAN SUPREME COURT: THE RELIGIOUS DENOMINATION AND ESSENTIAL PRACTICES TESTS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN RELIGION MAY 2019 By Coleman D. Williams Thesis Committee: Ramdas Lamb, Chairperson Helen Baroni Ned Bertz Abstract As a religiously diverse society and self-proclaimed secular state, India is an ideal setting to explore the complex and often controversial intersections between religion and law. The religious freedom clauses of the Indian Constitution allow for the state to regulate and restrict certain activities associated with religious practice. By interpreting the constitutional provisions for religious freedom, the judiciary plays an important role in determining the extent to which the state can lawfully regulate religious affairs. This thesis seeks to historicize the related development of two jurisprudential tests employed by the Supreme Court of India: the religious denomination test and the essential practices test. The religious denomination test gives the Court the authority to determine which groups constitute religious denominations, and therefore, qualify for legal protection. The essential practices test limits the constitutional protection of religious practices to those that are deemed ‘essential’ to the respective faith. From their origins in the 1950s up to their application in contemporary cases on religious freedom, these two tests have served to limit the scope of legal protection under the Constitution and legitimize the interventionist tendencies of the Indian state. Additionally, this thesis will discuss the principles behind the operation of the two tests, their most prominent criticisms, and the potential implications of the Court’s approach. -

Muslim Shrines and Multi-Religious Visitations in Hindus' City Of

Singh, Rana P.B. 2013. Muslim shrines & Multi-Religious in Banaras. Pilgrims & Pilgrimages , 121 Updated: 01 July 2013. 11,530 words; 8 Tables, 4 Figs. IV Revised/Final Draft…© the author> [396.13]. Singh, Rana P.B. 2013, ‘Muslim Shrines and Multi-Religious visitations in Hindus’ city of Banaras, India: Co-existential Scenario’; in, Pazos, Antón M. (ed.) Pilgrims and Pilgrimages as Peacemakers in Christianity, Judaism and Islam . Compostela International Studies in Pilgrimage History and Culture, vol. 4. [Proceedings of the Colloquium: 13-15 October 2010, sponsored by the Spanish National Research Council]. Ashgate Publ. Ltd., Farnham, Surrey UK: <chapter 7>, pp. 121 - 147. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- CHAPTER 7 Muslim Shrines and Multi-Religious Visitations in Hindus’ city of Banaras, India: Co-existential Scenario Prof. Dr. Rana P.B. Singh [Professor of Cultural Geography & Heritage Studies, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi; & Head, Department of Geography, Faculty of Science, Banaras Hindu University]. # Post at : New F - 7, Jodhpur Colony; Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, UP 221005. INDIA. Cell: +091-9838 119474. Email: [email protected] ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ By the loving wisdom doth the soul know life. What has it got to do with senseless strife of Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Arab, Turk? … Jalalludin Rumi (1207-1273) 1 Abstract . Banaras, known as cultural capital of India and Hindus’ sacred city, records about one-fourth of its total population (1.65 millions in 2010) as Muslims. The importance of Muslims in Banaras is noticed by existence of their 1388 shrines and sacred sites, in contrast to Hindus’ recording over 3300 shrines and sacred sites. Since the beginning of the CE 11th century Muslims started settled down here, with a predominance of the Sunni sect (90 per cent). -

Paper: Geoc-201(Social and Cultural Geography) Topics: Major Religious Group: World and India; Nature of Agricultural and Urban - Industrial Society

SUBJECT: GEOGRAPHY SEMESTER: UG 2nd (H) PAPER: GEOC-201(SOCIAL AND CULTURAL GEOGRAPHY) TOPICS: MAJOR RELIGIOUS GROUP: WORLD AND INDIA; NATURE OF AGRICULTURAL AND URBAN - INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY MAJOR RELIGIOUS GROUPS OF INDIA Religion in India is characterised by a diversity of religious beliefs and practices. India is officially a secular state and has no state religion. The Indian subcontinent is the birthplace of four of the world's major religions; namely Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism. According to the 2011 census, 79.8% of the population of India practices Hinduism, 14.2% adheres to Islam, 2.3% adheres to Christianity, 1.7% adheres to Sikhism, and 0.7% adheres to Buddhism. Zoroastrianism, Sanamahism and Judaism also have an ancient history in India, and each has several thousands of Indian adherents. Throughout India's history, religion has been an important part of the country's culture. Religious diversity and religious tolerance are both established in the country by the law and custom; the Constitution of India has declared the right to freedom of religion to be a fundamental right. Today, India is home to around 94% of the global population of Hindus. Most Hindu shrines and temples are located in India, as are the birthplaces of most Hindu saints. Prayagraj (formerly known as Allahabad) hosts the world's largest religious pilgrimage, Prayag Kumbh Mela, where Hindus from across the world come together to bath in the confluence of three sacred rivers of India: the Ganga, the Yamuna, and the Saraswati. The Indian diaspora in the West has popularized many aspects of Hindu philosophy such as yoga, meditation, Ayurvedic medicine, divination, karma, and reincarnation.The influence of Indian religions has been significant all over the world. -

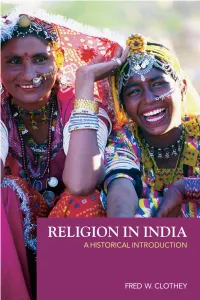

Religion in India: a Historical Introduction

Religion in India Religion in India is an ideal first introduction to India’s fascinating and varied religious history. Fred W. Clothey surveys the religions of India from prehistory through the modern period. Exploring the interactions between different religious movements over time, and engaging with some of the liveliest debates in religious studies, he examines the rituals, mythologies, arts, ethics, and social and cultural contexts of religion as lived in the past and present on the subcontinent. Key topics discussed include: • Hinduism, its origins, context and development over time • Other religions (such as Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Sikhism, Zoroastrianism, Jainism, and Buddhism) and their interactions with Hinduism • The influences of colonialism on Indian religion • The spread of Indian religions in the rest of the world • The practice of religion in everyday life, including case studies of pilgrimages, festivals, temples, and rituals, and the role of women Written by an experienced teacher, this student-friendly textbook is full of clear, lively discussion and vivid examples. Complete with maps and illustrations, and useful pedagogical features, including timelines, a comprehensive glossary, and recommended further reading specific to each chapter, this is an invaluable resource for students beginning their studies of Indian religions. Fred W. Clothey is Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies at the University of Pittsburgh. He is author and co-editor of numerous books and articles. He is the co-founder of the Journal of Ritual Studies and is also a documentary filmmaker. Religion in India A Historical Introduction Fred W. Clothey First published in the USA and Canada 2006 by Routledge 270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 100016 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon. -

"Religion": Protestant Presuppositions in the Critique of the Concept of Hindu

“HINDUISM” AND THE HISTORY OF “RELIGION”: PROTESTANT PRESUPPOSITIONS IN THE CRITIQUE OF THE CONCEPT OF HINDUISM Will Sweetman The claim that Hinduism is not a religion, or not a single religion, is so often repeated that it might be considered an axiom of research into the religious beliefs and practices of the Hindus, were it not typically ignored immediately after having been stated. The arguments for this claim in the work of several representative scholars are examined in order to show that they depend, implicitly or explicitly, upon a notion of religion which is too much influenced by Christian conceptions of what a religion is, a conception which, if it has not already been discarded by scholars of religion, certainly ought to be. Even where such Christian models are explicitly disavowed, the claim that Hinduism is not a religion can be shown to depend upon a particular religious conception of the nature of the world and our possible knowledge of it, which scholars of religion cannot share. Two claims which I take to have been established by recent work on the history of the concept “religion” provide the starting point for my argument here. The first is that, while the concept emerged from a culture which was still shaped by its Christian history, nevertheless the establishment of the modern sense of the term was the result of “a process of extracting the word from its Christian overtones” (Bossy 1982: 12).1 The second is that the concept, like all abstractions, im- plies a categorization of phenomena which is imposed upon rather than emergent from them: “religion” is not a natural kind. -

Religion in India Is Characterized by a Diversity of Religious Beliefs and Practices

Religion in India is characterized by a diversity of religious beliefs and practices. The Secularism in India means treatment of all religions equally by the state. India is a Secular State by the 42nd amendment act of Constitution in 1976. The Indian subcontinent is the birthplace of four of the world's major religions; namely Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism. Throughout India's history, religion has been an important part of the country's culture. Religious diversity and religious tolerance are both established in the country by the law and custom; the Constitution of India has declared the right to freedom of religion to be a fundamental right. Religion in India (2011 Census) Hinduism (79.80%) Islam (14.2%) Christianity (2.3%) Sikhism (1.7%) Buddhism (0.7%) Jainism (0.4%) Other religions (0.7%) Religion not specified (0.2%) Geography (U.G), SEM- II, Paper – C3T: Human Geography (Cultural Region: Religion) Northwest India was home to one of the world's oldest civilizations, the Indus valley civilisation. Today, India is home to around 90% of the global population of Hindus. Most Hindu shrines and temples are located in India, as are the birthplaces of most Hindu saints. Allahabad hosts the world's largest religious tour, Kumbha Mela, where Hindus from across the world come together to bathe in the confluence of three holy rivers of India: the Ganga, the Yamuna, and the Saraswati. The Indian diaspora in the West has popularized many aspects of Hindu philosophy such as yoga, meditation, Ayurvedic medicine, divination, karma, and reincarnation. The influence of Indian religions has been significant all over the world. -

Religion and Nationalism in India: the Case of Punjab, 1960 -199©

Religion and Nationalism in India: The Case of Punjab, 1960 -199© Harnik Deol Ph.D Department of Sociology The London School of Economics i 9 % l UMI Number: U093B28 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U093328 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 TWtses F <1400 I Abstract Religion and Nationalism in India: The Case of Punjab,1960 -1995 The research examines the factors which account for the emergence of ethno-nationalist movements in multi-ethnic and late industrialising societies such as India. The research employs a historical sociological approach to the study of nationalism. Opening with an interrogation of the classic theories of nationalism, the research shows the Eurocentric limitations of these works. By providing an account of the distinctive nature and development of Indian nationalism, it is maintained that the nature, growth, timing and scope of nationalist movements is affected by the level of development and the nature of the state and society in which they emerge. Using the theoretical framework developed here, the theses seeks to explain the nature and timing of breakaway movements in the Indian subcontinent.