Hinduism in India and Congregational Forms: Influences of Modernization and Social Networks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Facts About Religion in India | Pew Research Center

5 facts about religion in India | Pew Research Center https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/06/29/5-facts-about-re... MAIN MORE NEWS IN THE NUMBERS JUNE 29, 2018 5 facts about religion in India BY SAMIRAH MAJUMDAR Graffiti on a Mumbai wall. (Indranil Mukherjee/AFP/Getty Images) India is home to 1.4 billion people – almost one-sixth of the world’s population – who belong to a variety of ethnicities and religions. While 94% of the world’s Hindus live in India, there also are substantial populations of Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains and adherents of folk religions. For most Indians, faith is important: In a 2015 Pew Research Center survey, eight-in-ten Indians said religion is very important in their lives. Here are five facts about religion in India: 1 1 of 7 11/4/20, 2:51 PM 5 facts about religion in India | Pew Research Center https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/06/29/5-facts-about-re... India’s massive population includes not only the vast majority of the world’s Hindus, but also the second-largest group of Muslims within a single country, behind only Indonesia. By 2050, India’s Muslim population will grow to 311 million, making it the largest Muslim population in the world, according to Pew Research Center projections. Still, Indian Muslims are projected to remain a minority in their country, making up about 18% of the total population at midcentury, while Hindus figure to remain a majority (about 77%). India is a religiously pluralistic and multiethnic democracy – the largest 2 in the world. -

Religion in Modern India • Rel 3336 • Spring 2020

RELIGION IN MODERN INDIA • REL 3336 • SPRING 2020 PROFESSOR INFORMATION Jonathan Edelmann, Ph.D., University of Florida, Department of Religion, Anderson Hall [email protected]; (352) 392-1625 Office Hours: M,W,F • 9:30-10:30 AM or by appointment COURSE INFORMATION Course Meeting Time: Spring 2020 • M,W,F • Period 5, 11:45 AM - 12:35 PM • Matherly 119 Course Qualifications: 3 Credit Hours • Humanities (H), International (N), Writing (WR) 4000 Course Description: The modern period typically covers the years 1550 to 1850 AD. This course covers religion in India since the beginning of the Mughal empire in the mid-sixteenth century, to the formation of the independent and democratic Indian nation in 1947. The concentration of this course is on aesthetics and poetics, and their intersection with religion; philosophies about the nature of god and self in metaphysics or ontology; doctrines about non-dualism and the nature of religious experience; theories of interpretation and religious pluralism; and concepts of science and politics, and their intersection with religion. The modern period in India is defined by a diversity of religious thinkers. This course examines thinkers who represent the native traditions like Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism, as well as the ancient and classical traditions in philosophy and literature that influenced native religions in the modern period. Islam and Christianity began to interact with native Indian religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism during the modern period. Furthermore, Western philosophies, political theories, and sciences were also introduced during India’s modern period. The readings in this course focus on primary texts and secondary sources that critically portray and engage this complex and rich history of India’s modern period. -

The Star of Yoga Guidance from the Light

The Star of Yoga Guidance from the Light (From an upcoming book “Meditation For the Monkey Mind”) By Mas Vidal As we look up to the night sky we get a spectacular glimpse of the vast galaxy we see from earth. Stars abound through out the sky like mini suns each creating their own distinct light, some forming clusters and interesting configurations. There is an inherent quality in humanity to feel an attraction to light, be it sunlight or open spaces. It makes sense as we have come to understand the science behind energy we know that like attracts like. We realize there is great value that comes from being in the light, which breeds an optimism and greater awareness. In general people feel a kinship towards one another when they share something in common. A star’s light is symbolic of the highest ideal of every human being to live in love, light and harmony (sat, chit andanda) with nature and all aspects of life. The ancients have always looked to the stars for guidance, healing and understanding the cycles of nature. A star’s five points symbolize a connection to the five great elements (pancha maha bhutas) and reflects the gradation of energy from gross (earth) to subtle (sky). The mystical star of yoga provides guidance on the journey towards enlightenment as various pathways, with each empowering us to reach the culmination or purna as the true yogic ideal of living a fully integrated lifestyle. Such integration is based on a balance between spirit and ecology thus reminding us of the importance of responsibility in our thoughts, words and actions that can either connect us or create greater divide from the Divine. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

The Menstrual Taboo and Modern Indian Identity

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects 6-28-2017 The eM nstrual Taboo and Modern Indian Identity Jessie Norris Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Hindu Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Norris, Jessie, "The eM nstrual Taboo and Modern Indian Identity" (2017). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 694. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/694 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MENSTRUAL TABOO AND MODERN INDIAN IDENTITY A Capstone Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of History and Degree Bachelor of Anthropology With Honors College Distinction at Western Kentucky University By Jessie Norris May 2017 **** CE/T Committee: Dr. Tamara Van Dyken Dr. Richard Weigel Sharon Leone 1 Copyright by Jessie Norris May 2017 2 I dedicate this thesis to my parents, Scott and Tami Norris, who have been unwavering in their support and faith in me throughout my education. Without them, this thesis would not have been possible. 3 Acknowledgements Dr. Tamara Van Dyken, Associate Professor of History at WKU, aided and counseled me during the completion of this project by acting as my Honors Capstone Advisor and a member of my CE/T committee. -

Odisha Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Office Bearers

Odisha Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Office Bearers Chief Organiser 1 Shri Biren Mohan Patnaik Shri Biren Mohan Patnaik Chief Organiser Chief Organiser Odisha Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Odisha Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Congress Bhawan, Unit-2 A-91/1, Sahid Nagar Bhubaneshwar Opp.Aaykar Bhawan Odisha Bhubaneswar Tel: 09937010325, 09437010325 Odisha Mahila Organiser State Chief Instructor 1 Miss. Usha Rani Behera 1 Shri Ram Prasad Jaiswal Mahila Organiser Chief Instructor Odisha Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Odisha Pradesh Congress Seva Dal At-Jobra Road At/PO-Panposh Basti Cuttack Rourela-4 Odisha Distt-Sundergarh Tel-07978216221 Odisha Tel-09437117047 State Treasuer State Office Incharge 1 Shri Ratnakar Behera 1 Shri Jyotish Kumar Sahoo Treasurer Office Incharge Odisha Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Odisha Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Plot No.500/502 Plot No.743-P/12-A Near Krishna Tower Jameswar Bhawan Nayapalli,Bhubaneswar At/PO-Baramunda Odisha Bhubaneshwar Odisha Tel-9437307634 State Organisers 1 Shri Ashok Kumar Singh 2 Shri Rabindranath Behera Organiser Organiser Odisha Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Odisha Pradesh Congress Seva Dal At//PO-Anakhia At/PO-Telengapentha Distt-Jagatsinghpur Distt-Cuttack Odisha Odisha Tel-09439956517 Tel-09438126788 3 Smt. Trupti Das 4 Shri Benudhar Nayak Organiser Organiser Odisha Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Odisha Pradesh Congress Seva Dal At/PO-Tulsipur, Matha Sahi, At/PO-Daspalla Distt-Cuttack Distt-Nayagarh Odisha Odisha Tel-08895741510 Tel-08895412949 5 Smt. Bjaylaxmi Mahapatra 6 Ms. Nalini Behera Organiser Organiser Odisha Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Odisha Pradesh Congress Seva Dal At/PO-Bentapada At-Khairpur Via-Athagarh PO-Banamallpur Distt-Cuttack Via-Balipatna Odisha Distt-Khurda Tel-09437276083 Odisha Tel-09438300987 7 Shri Madhab Biswal 8 Shri Munu Saraf Organiser Organiser Odisha Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Odisha Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Vill-Bankoi At/PO-Sunaripada Distt-Khurda Distt-Sundergarh Odisha Odisha Tel-09556102676 Tel-09937235678 9 Shri Rajendra Prasad 10 Md. -

Conflict Between Freedom of Expression and Religion in India—A Case Study

Article Conflict between Freedom of Expression and Religion in India—A Case Study Amit Singh Centre for Social Studies, University of Coimbra, Colégio de S. Jerónimo Apartado 3087, 3000-995 Coimbra, Portugal; [email protected] Received: 24 March 2018; Accepted: 27 June 2018; Published: 29 June 2018 Abstract: The tussle between freedom of expression and religious intolerance is intensely manifested in Indian society where the State, through censoring of books, movies and other forms of critical expression, victimizes writers, film directors, and academics in order to appease Hindu religious-nationalist and Muslim fundamentalist groups. Against this background, this study explores some of the perceptions of Hindu and Muslim graduate students on the conflict between freedom of expression and religious intolerance in India. Conceptually, the author approaches the tussle between freedom of expression and religion by applying a contextual approach of secular- multiculturalism. This study applies qualitative research methods; specifically in-depth interviews, desk research, and narrative analysis. The findings of this study help demonstrate how to manage conflict between freedom of expression and religion in Indian society, while exploring concepts of Western secularism and the need to contextualize the right to freedom of expression. Keywords: freedom of expression; Hindu-Muslim; religious-intolerance; secularism; India 1. Background Ancient India is known for its skepticism towards religion and its toleration to opposing views (Sen 2005; Upadhyaya 2009), However, the alarming rise of Hindu religious nationalism and Islamic fundamentalism, and consequently, increasing conflict between freedom of expression and religion, have been well noted by both academic (Thapar 2015) and public intellectuals (Sorabjee 2018; Dhavan 2008). -

State and Religion in India: the Indian Secular Model1

Erik Reenberg Sand STATE AND RELIGION IN INDIA: THE INDIAN SECULAR MODEL1 Abstract This article attempts to characterize the so-called Indian secular model by examining the relation- ship between the state and religion as ratified by the Indian Constitution of 1950. It is shown how, in spite of the ideal of separating state and religion, the state in several cases was allowed to inter- vene in the affairs of religion. Thus, although the constitution allows individuals free choice of religion and religious denominations the right to establish and administer religious and educa- tional institutions, it also allows the state various means of interfering in religious matters. A major reason for this is the responsibility of the state to protect the rights of the various under- privileged groups in Indian society. The last part of the paper deals briefly with the growing cri- tique of the secular system and ideology from the side of Hindu nationalists and Indian intellec- tuals, a critique which is largely based on misuses of the system by the Indian political elites. Key words: India, religion, state, constitutionalism The overall aim of the present article is to offer a brief characterization of the so-called Indian secular model by examining the relationship between the state and religion as ratified by the Indian Constitution of 1950. In addition to this, the paper will deal briefly with an area where religious group practices still seem to resist secularization, namely the practice of personal laws, as well as with the growing critique of the secular system and ideology from the side of Hindu nationalists and Indian intellectuals. -

What Do You Know About Hinduism?

UWS An Inclusive Community UWS Multifaith Chaplaincy September 2008 What do you know about Hinduism? Followers of the teachings of the Vedas are called Hindus. Hindu staff and students form a substantial part of the UWS community. Acknowledging and respecting Hindu identities at UWS therefore requires, in part, a basic understanding of what Hinduism and being a Hindu is about. About Hinduism Hinduism originated and developed in India over the last 3,000-3,500 years. It is the majority religion in India. Hindus believe in one Supreme God who manifests him/herself in many different forms. Some of these include Krishna, Durga, Ganesh, Sakti (Devi), Vishnu, Surya, Siva and Skanda (Murugan). Hindus believe: • in the Vedas (scriptures) • there is one Supreme God who is the creator of the universe • in reincarnation • that everyone creates their own destiny (karma) There are four major Hindu denominations classified according to their respective focus of worship. Vaishnavism Vaishnavism worship Vishnu and his incarnations, particularly Krishna and Rama, as the Supreme God. Saivism Saivites worship Siva (also spelt Shiva) as the Supreme God. Shaktism Shaktas worship God as the Shakti, Sri Devi or the Divine Mother in her many forms. Hindu Dress Code Traditional Hindu women wear the sari. Traditional male Hindus wear the Smartism white cotton dhoti. Smarta Hindus view the different manifestations of God as equivalent. They accept all major Hindu gods and are commonly known as liberal or Women in particular may wear a dot (tilak) of turmeric powder or other non-sectarian. coloured substance on their foreheads as a symbol of their religion. -

Islam and Hinduism in the Eyes of Early European Travellers to India

Faraz Anjum * ISLAM AND HINDUISM IN THE EYES OF EARLY EUROPEAN TRAVELLERS TO INDIA Religion was an important identity marker in the early modern world. Whether in the East or the West, people distinguished themselves, among other things, with their adherence to a particular religion. In Europe, after Reformation in the early sixteenth century, the religious identities had got more sharpened and the Christian world was divided between the Catholics and the Protestants. Reformation strongly influenced the religious identities of European travellers and when they came into contact with the Indian religious beliefs and practices, they were “confronted with their own struggle for orientation. and the pattern for describing foreign religions was [thus] the pattern of differences between Catholicism and Protestantism.”1 While in India, Hinduism and Islam were the two dominant religions, though there were other minor religious denominations, like Budhists, Sikhs, and Parsees etc. The article is mainly concerned with the European representations of Islam and Hinduism in India. Focussing on the sixteenth and seventeenth century travel accounts of Europeans to India, it argues that these perceptions were strongly shaped by their belonging to Christian faith and their experiences of Europe. Most of European travellers considered Christianity as the only true religion and passed judgements on the Hindus and Muslims from a pure Christian perspective. They did not speak about them “without consigning them to eternal perdition.”2 This perception naturally resulted in their biased understanding of Indian religions. It is also a fact that some travellers were devoted missionaries and one of the principal motives of their travel to India was to convert the local population to Christianity. -

Cultural Dynamics

Cultural Dynamics http://cdy.sagepub.com/ Authoring (in)Authenticity, Regulating Religious Tolerance: The Implications of Anti-Conversion Legislation for Indian Secularism Jennifer Coleman Cultural Dynamics 2008 20: 245 DOI: 10.1177/0921374008096311 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cdy.sagepub.com/content/20/3/245 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Cultural Dynamics can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cdy.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cdy.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://cdy.sagepub.com/content/20/3/245.refs.html >> Version of Record - Oct 21, 2008 What is This? Downloaded from cdy.sagepub.com at The University of Melbourne Libraries on April 11, 2014 AUTHORING (IN)AUTHENTICITY, REGULATING RELIGIOUS TOLERANCE The Implications of Anti-Conversion Legislation for Indian Secularism JENNIFER COLEMAN University of Pennsylvania ABSTRACT This article explores the politicization of ‘conversion’ discourses in contemporary India, focusing on the rising popularity of anti-conversion legislation at the individual state level. While ‘Freedom of Religion’ bills contend to represent the power of the Hindu nationalist cause, these pieces of legislation refl ect both the political mobility of Hindutva as a symbolic discourse and the prac- tical limits of its enforcement value within Indian law. This resurgence, how- ever, highlights the enduring nature of questions regarding the quality of ‘conversion’ as a ‘right’ of individuals and communities, as well as reigniting the ongoing battle over the line between ‘conversion’ and ‘propagation’. Ul- timately, I argue that, while the politics of conversion continue to represent a decisive point of reference in debates over the quality and substance of reli- gious freedom as a discernible right of Indian democracy and citizenship, the widespread negative consequences of this legislation’s enforcement remain to be seen. -

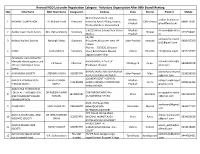

Revised NGO List Under Registration Category

Revised NGO List under Registration Category - Voluntary Organization After 80th Board Meeting SNo NGO Name NGO Head Name Designation Address State District Email id Mobile 48 Panchwati Ward, Opp. Madhya aadhar.foundation 1 AADHAR FOUNDATION ER. Mahesh Kinth President Narendra Ayush Dhaba, Poama, Chhindwara 8989173581 Pradesh @rediffmail.com P/o Kundali Kala, Parasia Road E-4/223,Arera Colony,Near 10 no. Madhya [email protected] 2 Aadhar Gyan Dhatri Samiti Mrs. Ratna Mukerji Secretary Bhopal 9755554401 Market Pradesh m S2/258 adityawelfaresocie 3 Aaditya Welfare Society Narsingh Yadav Secretary Bhojubeer,Bhojubeer,Near UP Uttar Pradesh Varanasi 9936437260 [email protected] College Plot No. - 70/3530, (Ground 4 AAINA Sneha Mishra Secretary Floor),Behind Hotel Mayfair Odisha Khordha [email protected] 9437017967 Lagoon,Jaydev Vihar Aakanksha Lions School for Mentally Handicapped a unit Awanti Vihar,,In front of aakankshalsmh@y 5 K K Nayak Chairman Chattisgarh Raipur 9826845678 of Lions Club Raipur Sewa Bhaktawar Bhawan ahoo.com Samiti KHARAGIPUR,GANGAUPUR,RAM akankshasocietyma 6 AAKANKSHA SOCIETY JITENDRA YADAV SECRETARY Uttar Pradesh Mau 9258038100 AUPUR SUWAH LINK MARG [email protected] 120 NEAR GOVT HOSPITAL AARIOLA PRAKASH PUNJ BALVEER SINGH Madhya balveer.singhrajput 7 CHAIRMAN HARDA,AWASTHI COMPOUND Harda 9009616393 SHIKSHA SAMITI RAJPUT Pradesh @yahoo.com HARDA,HARDA AAROGYAA FOUNDATION FOR HEALTH PROMOTION DR RAJESH KUMAR COAT BAZAR,WARD No aarogyaafoundatio 8 SECERETARY Bihar Sitamarhi 9934691872 AND COMMUNITY BASED SUMAN 13,MAHARANI STHAN