Conflict Between Freedom of Expression and Religion in India—A Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unravelling the Indian Conception of Secularism: Tremors of the Pandemic and Beyond

Katrak, N and Kulkarni, S. 2021. Unravelling the Indian Conception of Secularism: Tremors of the Pandemic and Beyond. Secularism and Nonreligion, 10: 4, pp. 1–12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/snr.145 RESEARCH ARTICLE Unravelling the Indian Conception of Secularism: Tremors of the Pandemic and Beyond Malcolm Katrak* and Shardool Kulkarni† The State’s engagement with religion has formed one of the recurring themes of conflict in India’s demo- cratic experiment. The Indian model of secularism, which evolved in an attempt to resolve this conflict, has distinguished itself from separation-model secularism. This paper seeks to analyse the impact of the measures undertaken during the COVID-19 pandemic on the Indian understanding of secularism. To this end, it provides an overview of the nature and evolution of Indian secularism. Thereafter, it encapsulates the steps taken by the State to meet the exigencies of the present contagion and attempts to gauge the impact of the said steps on the jurisprudence on religious freedoms. It then seeks to contextualise this impact by using it to inform the Indian conception of secularism and, thereby, promote a richer, more holistic understanding of how a deeply divided society has functioned as a secular State for seven decades. 1 Introduction much of the globe in crisis, chaos and panic, has not left Religion has frequently formed the bone of socio-politi- India untouched. The pandemic is not only a public health cal contention in India; a country whose social milieu is crisis of monumental proportions but has had cascading characterised in equal parts by its multicultural diver- effects on almost all aspects of public life across the globe sity and inter-religious strife. -

The Contest of Indian Secularism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto THE CONTEST OF INDIAN SECULARISM Erja Marjut Hänninen University of Helsinki Faculty of Social Sciences Political History Master’s thesis December 2002 Map of India I INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................1 PRESENTATION OF THE TOPIC ....................................................................................................................3 AIMS ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 SOURCES AND LITERATURE ......................................................................................................................7 CONCEPTS ............................................................................................................................................... 12 SECULARISM..............................................................................................................14 MODERNITY ............................................................................................................................................ 14 SECULARISM ........................................................................................................................................... 16 INDIAN SECULARISM .............................................................................................................................. -

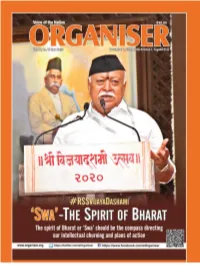

Organiser-Main-File-November-1-1.Pdf

l ISSN : 0030-5014 l Vol. 72 l No. 19 l November 1, 2020 l OPINION 24 Either Black or White 100 YRS OF MOPLAH RIOTS 26 Flight of the Bulbuls ANALYSIS 30 Apostate Europe! 06 COVER STORY/ #RSSVIJAYADASHAMI 40 ‘Hard Truth’ over GDP Hindutva is the acknowledgement REPORTS of our Selfhood 34 ‘Fear is going to change ANALYSIS sides’: Macron’s mes- 16 sage to Islamists Rashtra Sevika Samiti: An organisation of women, by 36 Madrasas: The Holy women, for the Nation Cow for Congress in Rajasthan INDIC WISDOM-II 50 Adhyatma & Spirituality COLUMN 04 Readers’ Forum 20 OPINION/ ROSHNI ACT 38 REPORT/BIHAR ASSEMBLY 05 Editorial SCAM-J&K ELECTIONS 2020 15 News Round-Up Systemised Loot of the NDA leaving nothing to 46 Defence Scan System by the System chance Editor: Prafulla Ketkar l Asso Editor : G Sreedathan l Sr Reporter : Nishant Kumar Azad l Web Consultant: Ganesh Krishnan R l Associate Art Director: Shashi Mohan Rawat l Sr Graphic Designer: Mukta Surma Kataria DTP Operator: Manoj Kumar Singh l Cover Page Design : Shashi Mohan Rawat l E-mail: [email protected] l Website: www.organiser.org l Phones: 011-47642018, 20, 22 Bharat Prakashan (Delhi) Ltd. Email : [email protected] Street, Paharganj, Office: Vishva Samvaad Kendra, Managing Director Subscription New Delhi-110055 First Floor, Dr G B Pant Marg, Bharat Bhushan Arora Arvind Sinha : 011-47642001 Sanskriti Bhawan, 2322, Lohia Panth, Jiamau, Hazratganj, General Manager Agency Laxmi Narain Street, Paharganj, Lucknow Jitendra Mehta Upender Singh : 011-47642000 New Delhi-110055 Director & Publisher Customer Complaint Cell Gujrat Office : Bengaluru Bureau: Bihari Lal Singhal Phone : 011-47642015 B-1, Parav Apartment, Office: Vikrama Prakashan, Email : [email protected] Behind LG Hospital, Mukti Maidan, No. -

Secularism: Its Content and Context

SECULARISM: ITS CONTENT AND CONTEXT BY AKEEL BILGRAMI COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY OCTOBER, 2011 Abstract This paper addresses two sets of questions. First, questions about the meaning of secularism and second questions about its justification and implementation. It is argued that Charles Taylor‘s recent efforts to redefine secularism for a time when we have gone ‗beyond toleration‘ to multiculturalism in liberal politics, are based on plausible (and laudable) political considerations that affect the question of justification and implementation, but leave unaffected the question of the meaning and content of secularism. An alternative conceptualization of secularism is offered, from the one he proposes, while also addressing his deep and understandable concerns about the politics of secularism for our time. In the characterization of secularism offered, it turns out that secularism has its point and meaning, not in some decontextualized philosophical argument, but only in contexts that owe to specific historical trajectories, with specific political goals to be met. 1 1. I begin with three fundamental features of the idea of ‗secularism.‘ I will want to make something of them at different stages of the passage of my argument in this paper for the conclusion—among others—that the relevance of secularism is contextual in very specific ways.1 If secularism has its relevance only in context, then it is natural and right to think that it will appear in different forms and guises in different contexts. But I write down these opening features of secularism at the outset because they seem to me to be invariant among the different forms that secularism may take in different contexts. -

Protection of Lives and Dignity of Women Report on Violence Against Women in India

Protection of lives and dignity of women Report on violence against women in India Human Rights Now May 2010 Human Rights Now (HRN) is an international human rights NGO based in Tokyo with over 700 members of lawyers and academics. HRN dedicates to protection and promotion of human rights of people worldwide. [email protected] Marukou Bldg. 3F, 1-20-6, Higashi-Ueno Taitou-ku, Tokyo 110-0015 Japan Phone: +81-3-3835-2110 Fax: +81-3-3834-2406 Report on violence against women in India TABLE OF CONTENTS Ⅰ: Summary 1: Purpose of the research mission 2: Research activities 3: Findings and Recommendations Ⅱ: Overview of India and the Status of Women 1: The nation of ―diversity‖ 2: Women and Development in India Ⅲ: Overview of violence and violation of human rights against women in India 1: Forms of violence and violation of human rights 2: Data on violence against women Ⅳ: Realities of violence against women in India and transition in the legal system 1: Reality of violence against women in India 2: Violence related to dowry death 3: Domestic Violence (DV) 4: Sati 5: Female infanticides and foeticide 6: Child marriage 7: Sexual violence 8: Other extreme forms of violence 9: Correlations Ⅴ: Realities of Domestic Violence (DV) and the implementation of the DV Act 1: Campaign to enact DV act to rescue, not to prosecute 2: Content of DV Act, 2005 3: The significance of the DV Act and its characteristics 4: The problem related to the implementation 5: Impunity of DV claim 6: Summary Ⅵ: Activities of the government, NGOs and international organizations -

5 Facts About Religion in India | Pew Research Center

5 facts about religion in India | Pew Research Center https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/06/29/5-facts-about-re... MAIN MORE NEWS IN THE NUMBERS JUNE 29, 2018 5 facts about religion in India BY SAMIRAH MAJUMDAR Graffiti on a Mumbai wall. (Indranil Mukherjee/AFP/Getty Images) India is home to 1.4 billion people – almost one-sixth of the world’s population – who belong to a variety of ethnicities and religions. While 94% of the world’s Hindus live in India, there also are substantial populations of Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains and adherents of folk religions. For most Indians, faith is important: In a 2015 Pew Research Center survey, eight-in-ten Indians said religion is very important in their lives. Here are five facts about religion in India: 1 1 of 7 11/4/20, 2:51 PM 5 facts about religion in India | Pew Research Center https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/06/29/5-facts-about-re... India’s massive population includes not only the vast majority of the world’s Hindus, but also the second-largest group of Muslims within a single country, behind only Indonesia. By 2050, India’s Muslim population will grow to 311 million, making it the largest Muslim population in the world, according to Pew Research Center projections. Still, Indian Muslims are projected to remain a minority in their country, making up about 18% of the total population at midcentury, while Hindus figure to remain a majority (about 77%). India is a religiously pluralistic and multiethnic democracy – the largest 2 in the world. -

Islam and Justice AAIMS Inaugural Conference on the Study of Islam and Muslim Societies

Islam and Justice AAIMS Inaugural Conference on the Study of Islam and Muslim Societies Date: 18-19 December 2017 Venue: Copland Theatre, 198 Berkeley Street, The University of Melbourne Parkville, VIC 3010 Sponsors National Centre of Excellence for Islamic Studies Asia Institute School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, Faculty of Arts University of Melbourne Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation Deakin University Institute for Religion, Politics and Society Australian Catholic University Routledge Taylor and Francis Group Conference Conveners Professor Abdullah Saeed AM Sultan of Oman Chair in Islamic Studies | 3 Director, National Centre of Excellence for Islamic Studies University of Melbourne Professor Vedi Hadiz Deputy Director, Asia Institute University of Melbourne Conference Committee Professor Shahram Akbarzadeh Deputy Director (International), Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation Deakin University Associate Professor Richard Pennell Al-Tajir Lecturer in Middle Eastern & Islamic History School of Historical and Philosophical Studies University of Melbourne Dr Joshua Roose Director, Institute for Religion Politics and Society The Australian Catholic University National Centre of Excellence for Islamic Studies (NCEIS) The National Centre of Excellence for Islamic Studies aims to advance the knowledge and | 4 understanding of the rich traditions and modern complexities of Islam, and to profile Australia's strengths in the field of Islamic studies. The Centre's activities will focus on issues of significance and relevance to Islam and Muslims in the contemporary period with a special focus on Australia. The Centre's courses aim to provide a knowledge and skill foundation for students aspiring to religious and community leadership roles in Australia and will provide opportunities for professional development in relevant areas. -

Human Rights and Creed Research and Consultation Report

Human Rights and Creed Research and consultation report ISBN: 978-1-4606-3360-1 (Print) 978-1-4606-3361-8 (HTML) 978-1-4606-3362-5 (PDF) © 2013 Queen’s Printer for Ontario Available in various formats Also available online: www.ohrc.on.ca Disponible en français Human rights and creed research and consultation report Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 1. Setting the context................................................................................................... 1 2. The purpose of this report........................................................................................ 2 3. Criteria for assessing and developing human rights policy ...................................... 2 II. Executive summary................................................................................................... 3 III. Background and context ......................................................................................... 7 Key questions .............................................................................................................. 7 1. Current social and demographic trends ................................................................... 7 1.1 Diversity of creed beliefs and practices.............................................................. 7 1.2 Individual belief and practice............................................................................ 10 1.3 Policy and program trends .............................................................................. -

Religion in Modern India • Rel 3336 • Spring 2020

RELIGION IN MODERN INDIA • REL 3336 • SPRING 2020 PROFESSOR INFORMATION Jonathan Edelmann, Ph.D., University of Florida, Department of Religion, Anderson Hall [email protected]; (352) 392-1625 Office Hours: M,W,F • 9:30-10:30 AM or by appointment COURSE INFORMATION Course Meeting Time: Spring 2020 • M,W,F • Period 5, 11:45 AM - 12:35 PM • Matherly 119 Course Qualifications: 3 Credit Hours • Humanities (H), International (N), Writing (WR) 4000 Course Description: The modern period typically covers the years 1550 to 1850 AD. This course covers religion in India since the beginning of the Mughal empire in the mid-sixteenth century, to the formation of the independent and democratic Indian nation in 1947. The concentration of this course is on aesthetics and poetics, and their intersection with religion; philosophies about the nature of god and self in metaphysics or ontology; doctrines about non-dualism and the nature of religious experience; theories of interpretation and religious pluralism; and concepts of science and politics, and their intersection with religion. The modern period in India is defined by a diversity of religious thinkers. This course examines thinkers who represent the native traditions like Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism, as well as the ancient and classical traditions in philosophy and literature that influenced native religions in the modern period. Islam and Christianity began to interact with native Indian religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism during the modern period. Furthermore, Western philosophies, political theories, and sciences were also introduced during India’s modern period. The readings in this course focus on primary texts and secondary sources that critically portray and engage this complex and rich history of India’s modern period. -

Journal of the National Human Rights Commission India Volume – 16 2017 EDITORIAL BOARD Justice Shri H

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION INDIA Volume – 16 2017 EDITORIAL BOARD Justice Shri H. L. Dattu Chairperson, NHRC Justice Shri P. C. Ghose Prof. Ranbir Singh Member, NHRC Vice-Chancellor, National Law University, Dwarka, New Delhi Justice Shri D. Murugesan Prof. T. K. Oommen Member, NHRC Emeritus Professor, Centre for the Study of Social Systems, School of Social Sciences, Shri S. C. Sinha Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Member, NHRC Smt. Jyotika Kalra Prof. Sanjoy Hazarika Member, NHRC Director, Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, New Delhi Shri Ambuj Sharma Prof. S. Parasuraman Secretary General, NHRC Director, Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai Shri J. S. Kochher Prof. Ved Kumari Joint Secretary (Trg. & Res.), Faculty of Law, Law Centre-I, NHRC University of Delhi, Delhi Dr. Ranjit Singh Prof. (Dr.) R. Venkata Rao Joint Secretary (Prog. & Admn.), Vice-Chancellor, National Law School NHRC of India University, Bangalore EDITOR Shri Ambuj Sharma, Secretary General, NHRC EDITORIAL ASSISTANCE Dr. M. D. S. Tyagi, Joint Director (Research), NHRC Shri Utpal Narayan Sarkar, AD (Publication), NHRC National Human Rights Commission Manav Adhikar Bhawan, C-Block, GPO Complex, INA New Delhi – 110 023, India ISSN : 0973-7596 ©2017, National Human Rights Commission All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of the Publisher. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in the articles incorporated in the Journal are of the authors and not of the National Human Rights Commission. The Journal of the National Human Rights Commission, Published by Shri Ambuj Sharma, Secretary General on behalf of the National Human Rights Commission, Manav Adhikar Bhawan, C-Block, GPO Complex, INA, New Delhi – 110 023, India. -

Religious Freedom As Equality 133 Frederick Mark Gedicks

Routledge Handbook of Law and Religion The field of law and religion studies has undergone a profound transformation over the last 30 years, looking beyond traditional relationships between State and religious communities to include rights of religious liberty and the role of religion in the public space. This handbook features new, specially commissioned papers by a range of eminent scholars that offer a comprehensive overview of the field of law and religion. The book takes on an interdisciplinary approach, drawing from anthropology, sociology, theology and political science in order to explore how laws and court decisions concerning religion contribute to the shape of the public space. Key themes within the book include: • religious symbols in the public space; • religion and security; • freedom of religion and cultural rights; • defamation and hate speech; and • gender, religion and law. This advanced level reference work is essential reading for students, researchers and scholars of law and religion, as well as policy makers in the field. Silvio Ferrari is professor of Law and Religion at the University of Milan. He is Life Honorary President of the International Consortium for Law and Religion Studies and is an Editor-in- Chief of the Oxford Journal of Law and Religion. He received the 2012 Distinguished Service Award from the International Center for Law and Religion Studies. ‘Few areas of contemporary legal scholarship have developed so exponentially in so short a space of time as the interface between law and religion. This outstanding Handbook not only synthesises and systematises that body of scholarship but firmly anchors it within those broader interdisciplinary frameworks which are essential to its understanding. -

State and Religion in India: the Indian Secular Model1

Erik Reenberg Sand STATE AND RELIGION IN INDIA: THE INDIAN SECULAR MODEL1 Abstract This article attempts to characterize the so-called Indian secular model by examining the relation- ship between the state and religion as ratified by the Indian Constitution of 1950. It is shown how, in spite of the ideal of separating state and religion, the state in several cases was allowed to inter- vene in the affairs of religion. Thus, although the constitution allows individuals free choice of religion and religious denominations the right to establish and administer religious and educa- tional institutions, it also allows the state various means of interfering in religious matters. A major reason for this is the responsibility of the state to protect the rights of the various under- privileged groups in Indian society. The last part of the paper deals briefly with the growing cri- tique of the secular system and ideology from the side of Hindu nationalists and Indian intellec- tuals, a critique which is largely based on misuses of the system by the Indian political elites. Key words: India, religion, state, constitutionalism The overall aim of the present article is to offer a brief characterization of the so-called Indian secular model by examining the relationship between the state and religion as ratified by the Indian Constitution of 1950. In addition to this, the paper will deal briefly with an area where religious group practices still seem to resist secularization, namely the practice of personal laws, as well as with the growing critique of the secular system and ideology from the side of Hindu nationalists and Indian intellectuals.