A Study of the Patterns of Unrest in the Springfield Public Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20 Gallon Galvanized Sheet Steel with Cover

' „ « PAGE EIGHTEEN FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 26, 1966 fianrh^st^r lEorning f^ralb Arcrage Daily Net Preae Run The W oitlier For the Week EiUM ; eC V. a. W esthe ronvm rr M . IN * The Rev. and Mrs. C. Henry Anderson, 157 Pitkin St., have M * ae eeM, About Town returned after two weeks of va World Day Prayer Service 14,126 cationing with relatives at Fort The Chsmlnade Muelcal Club ORANGE HALL Member et tke A «0t Lauderdale, Fla. Pastor Ander Bm eee of OlnidatlM will meet Monday at 8 p.m. In son will preach at Emanuel Set at St. Mary^s March 5 the Federation Room at Center Manchetter^A City of Village Charm Lutheran Church Sunday. Oongreifatlonal Church. "What Inspired Compo9er'.<i Romantic Mrs. Royal J. Gibson, chair-facilities and milk for the Lt. and Mrs. Carl E. Carl.son Aivorttalng ea Page If) PRICE SEVEN CENTO Work.s" will be the theme of the man of evangelism and spiritu young children will be provided. VOL. LXXXIV, NO. 126 (TWELVE PAGES—TV SECTION) MANCHESTER, CONN., SA'TURDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 1965 pro(fram. Mrs. »CharIes Lam- Jr. left yesterday by plane for More than 13S nations in aix Frankfurt, Germany, where Lt. al life at the United Church of oert, president, is in chargre of continents 'will observe March Carlson will be stationed with Christ, West Hartford, will be 5 as World Day of Prayer, now tfie entertainment. The meetingr the U.S. Air Force. The Carl- the guest speaker at the Man BINGO ia open to all women interested in its 79th year. -

Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : a Finding Aid

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids and Research Guides for Finding Aids: All Items Manuscript and Special Collections 5-1-1994 Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives. James Anthony Schnur Hugh W. Cunningham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all Part of the Archival Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives.; Schnur, James Anthony; and Cunningham, Hugh W., "Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid" (1994). Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items. 19. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all/19 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids and Research Guides for Manuscript and Special Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection A Finding Aid by Jim Schnur May 1994 Special Collections Nelson Poynter Memorial Library University of South Florida St. Petersburg 1. Introduction and Provenance In December 1993, Dr. Hugh W. Cunningham, a former professor of journalism at the University of Florida, donated two distinct newspaper collections to the Special Collections room of the USF St. Petersburg library. The bulk of the newspapers document events following the November 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy. A second component of the newspapers examine the reaction to Richard M. Nixon's resignation in August 1974. -

May 23, 1898, at 8 O'clock P

PRICE THREE CENTS. MISCELLANEOUS. States Consul George W. when Roosevolt, Hoate an intention to warn all whom it isked to take an active part in the Hi3- may concern that Spain is ready to resist sano-Amerioan war, declined, saying: in the war of any uujustiflablo sohemes of aggression ESCAPE. ‘I was wounded secession a 'rora whatever quarter they may come. TROOPS lozen times and have paid my debt to my These movements 10,000 have reference to the AWFUL TROUBLE. jountry. An American never pays the idea that be to the same debt twice.” Spain may helpful _ MUST power in the event of an SPAIN SUE FOR PEACE. Anglo-Saxon Disease of the Kidneys Are CERVmTMiY lETllii illianoe.” Always Serious. Impossible for Genera to WliTTO PORTLAND, ire Now Tenting at San Disease is Ca- Get Awry. Bright’s w Spanish Admiral Expected Back at Francisco, of the Fwo tarrh Kidneys. Martinique. Her Friends Will Force Her to do Companies Volunteers Assigned to Fort Preble. Pe-ru-na Cures Catarrh, Even MOST DESPERATE of These WITHOUT VOLUNTEERS READY TO Organs. [Copyright, 1898, by the Associated Press) at CONFLICT IN HISTORY. So First St. Pierre, Martinique, May 23.—Ad- Opportunity. Camp Haven, Nlantio, Conn., May 22. START FOR MANILA. —Col. -RU-NA is miral Cervera's squadron, It is reported Burdett, the commandant of this I rendezvous of the Connecticut volunteers something m good authority, will return to these recommend this afternoon received from Capt. Craw- waters to coal. It is known that a turn- ford at Fort New a to everyone. -

President's Daily Diary Collection (Box 78) at the Gerald R

Scanned from the President's Daily Diary Collection (Box 78) at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDENT GERALD R. FORD PLACE DAY BEGAN DATE (Mo., Day, Yr.) THE WHITE HOUSE NOVEMBER 7, 1975 WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME DAY 12:01 a.m. FRIDAY TIME "B :.a ~ ~ ACTIVITY r-~In---'--~O-ut--~ I ! 12:01 12:11 P The President talked with the First Lady. 7:42 The President had breakfast. 8:16 The President went to the Oval Office. 9:14 9:17 R The President talked with his son, Steve. 9:18 The President telephoned Congressman John N. Er1enborn (R-I11inois). The call was not completed. 9:22 The President went to the South Grounds of the White House. 9:22 9:30 The President flew by helicopter from the South Grounds to Andrews AFB, Maryland. For a list of passengers, see APPENDIX "A." 9:35 10:45 The President flew by the "Spirit of '76" from Andrews AFB to Westover AFB, Chicopee, Massachusetts. For a list of passengers, see APPENDIX "B." 10:45 The President was greeted by: Col. Billy M. Knowles, Commander of the 439th Tactical Airlift Wing Lt. Col. Jack P. Fergason, Commander of the 439th Combat Support Group Edward P. Ziemba, Mayor of Chicopee, Massachusetts William Sullivan, Mayor of Springfield, Massachusetts Lisa Chabasz, Little Miss Massachusetts 10:55 11:15 The President motored from Westover AFB to the Baystate West Hotel, 1500 Main Street, Springfield, Massachusetts. He was accompanied by: John A. Volpe, Ambassador from the U.S. -

Appendix File 1984 Continuous Monitoring Study (1984.S)

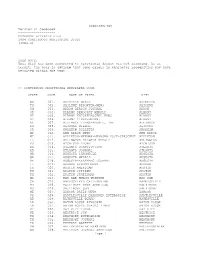

appcontm.txt Version 01 Codebook ------------------- CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE 1984 CONTINUOUS MONITORING STUDY (1984.S) USER NOTE: This file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As as result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. >> CONTINUOUS MONITORING NEWSPAPER CODE STATE CODE NAME OF PAPER CITY WA 001. ABERDEEN WORLD ABERDEEN TX 002. ABILENE REPORTER-NEWS ABILENE OH 003. AKRON BEACON JOURNAL AKRON OR 004. ALBANY DEMOCRAT-HERALD ALBANY NY 005. ALBANY KNICKERBOCKER NEWS ALBANY NY 006. ALBANY TIMES-UNION, ALBANY NE 007. ALLIANCE TIMES-HERALD, THE ALLIANCE PA 008. ALTOONA MIRROR ALTOONA CA 009. ANAHEIM BULLETIN ANAHEIM MI 010. ANN ARBOR NEWS ANN ARBOR WI 011. APPLETON-NEENAH-MENASHA POST-CRESCENT APPLETON IL 012. ARLINGTON HEIGHTS HERALD ARLINGTON KS 013. ATCHISON GLOBE ATCHISON GA 014. ATLANTA CONSTITUTION ATLANTA GA 015. ATLANTA JOURNAL ATLANTA GA 016. AUGUSTA CHRONICLE AUGUSTA GA 017. AUGUSTA HERALD AUGUSTA ME 018. AUGUSTA-KENNEBEC JOURNAL AUGUSTA IL 019. AURORA BEACON NEWS AURORA TX 020. AUSTIN AMERICAN AUSTIN TX 021. AUSTIN CITIZEN AUSTIN TX 022. AUSTIN STATESMAN AUSTIN MI 023. BAD AXE HURON TRIBUNE BAD AXE CA 024. BAKERSFIELD CALIFORNIAN BAKERSFIELD MD 025. BALTIMORE NEWS AMERICAN BALTIMORE MD 026. BALTIMORE SUN BALTIMORE ME 027. BANGOR DAILY NEWS BANGOR OK 028. BARTLESVILLE EXAMINER-ENTERPRISE BARTLESVILLE AR 029. BATESVILLE GUARD BATESVILLE LA 030. BATON ROUGE ADVOCATE BATON ROUGE LA 031. BATON ROUGE STATES TIMES BATON ROUGE MI 032. BAY CITY TIMES BAY CITY NE 033. BEATRICE SUN BEATRICE TX 034. BEAUMONT ENTERPRISE BEAUMONT TX 035. BEAUMONT JOURNAL BEAUMONT PA 036. -

Transnational Finnish Mobilities: Proceedings of Finnforum XI

Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen This volume is based on a selection of papers presented at Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) the conference FinnForum XI: Transnational Finnish Mobili- ties, held in Turku, Finland, in 2016. The twelve chapters dis- cuss two key issues of our time, mobility and transnational- ism, from the perspective of Finnish migration. The volume is divided into four sections. Part I, Mobile Pasts, Finland and Beyond, brings forth how Finland’s past – often imagined TRANSNATIONAL as more sedentary than today’s mobile world – was molded by various short and long-distance mobilities that occurred FINNISH MOBILITIES: both voluntarily and involuntarily. In Part II, Transnational Influences across the Atlantic, the focus is on sociocultural PROCEEDINGS OF transnationalism of Finnish migrants in the early 20th cen- tury United States. Taken together, Parts I and II show how FINNFORUM XI mobility and transnationalism are not unique features of our FINNISH MOBILITIES TRANSNATIONAL time, as scholars tend to portray them. Even before modern communication technologies and modes of transportation, migrants moved back and forth and nurtured transnational ties in various ways. Part III, Making of Contemporary Finn- ish America, examines how Finnishness is understood and maintained in North America today, focusing on the con- cepts of symbolic ethnicity and virtual villages. Part IV, Con- temporary Finnish Mobilities, centers on Finns’ present-day emigration patterns, repatriation experiences, and citizen- ship practices, illustrating how, globally speaking, Finns are privileged in their ability to be mobile and exercise transna- tionalism. Not only is the ability to move spread very uneven- ly, so is the capability to upkeep transnational connections, be they sociocultural, economic, political, or purely symbol- ic. -

The Puerto Rican Community of Western Massachusetts, 1898-1960” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 43, No

Joseph Carvalho III, “The Puerto Rican Community of Western Massachusetts, 1898-1960” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 43, No. 2 (Summer 2015). Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/ number/ date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.wsc.ma.edu/mhj. 34 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Summer 2015 War Ally Following the Spanish-American War in 1898, the U.S. annexed the island of Puerto Rico, where members of the 2nd Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment spent time after a battle in Cuba. The image above shows a flag used by a Puerto Rican regiment, the Third Provisional Battalion, deployed by Spain to defend Cuba during the Spanish- American War. After the war, the unit became the Porto Rico Voluntary Infantry under U.S. command. By 1920, it was the 65th Regiment, U.S. Infantry. 35 The Puerto Rican Community of Western Massachusetts, 1898–1960 JOSEPH CARVALHO III Abstract: This article attempts to chronicle the earliest connections between Western Massachusetts and Puerto Rico, and the experiences of earliest Puerto Rican residents of the region. Regional newspapers with special emphasis on the largest three newspapers in Western Massachusetts—the Springfield Republican, the Springfield Daily News, and the Springfield Union; the U.S. -

Looking Backward 2000-1887 (Oxford World's Classics)

’ LOOKING BACKWARD 2000–1887 E B was born in Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts, in March . He inherited his parents’ religious commitment (his father was a Baptist clergyman) and was baptized in . Having failed the medical examination at West Point, the United States Military Academy, he entered Union College in Schenectady, New York, in . The following year Bellamy visited his cousin in Dresden, where he encountered German socialism at first hand, and they travelled across Europe. In he began legal training in Springfield, Massachusetts, qualifying as a barrister in . He briefly opened an independent practice in Chicopee Falls, but soon became a journalist, working for the New York Post before returning to Massachusetts to become literary editor of the Springfield Union. In the early s he seems to have lost his religious conviction, though not his spiritual commitment, and in composed a lengthy philosophical essay setting out a ‘Religion of Solidarity’. Bellamy began to write fiction in the mid-s, publishing some twenty short stories and four novels between and , many of them in respected magazines like the Atlantic Monthly and Lip- pincott’s. Bellamy started work on Looking Backward in ; it was published in and became a best-seller in its second edition of . Thereafter Bellamy devoted himself to promoting its ideas, speaking at the meetings of various Bellamy Clubs and contributing articles to both The Nationalist, a paper set up to publicize these ideas, and its successor, The New Nation, which he also edited. He published Equality, a sequel to Looking Backward, in . He died in May in Chicopee Falls, where he had lived most of his life, leaving behind his wife, Emma Sanderson, and a son and daughter. -

Reelnumber Title City Begindate Enddate 56492 Volunteer AL

ReelNumber Title City BeginDate EndDate 56492 Volunteer AL - Athens 4/23/1864 4/23/1864 56492 Mobile Advertiser and Register AL - Mobile 11/15/1862 11/15/1862 56492 Weekly Advertiser and Register AL - Mobile 2/8/1864 2/8/1864 56492 Federal Union AL - Selma 5/13/1865 5/13/1865 54815 World's Cresset AR - Leachville 12/26/1918 12/26/1918 13833 Critic AR - Piggott 6/11/1915 6/11/1915 54825 Sacramento Weekly Union CA - Sacramento 4/12/1876 4/12/1876 54825 Sacramento Weekly Union CA - Sacramento 4/26/1876 4/26/1876 54825 Sacramento Weekly Union CA - Sacramento 8/2/1876 8/2/1876 54824 Enterprise and Co-Operator CA - San Francisco 5/25/1872 5/25/1872 54825 Spirit of the Times (& Underwriter’s J CA - San Francisco 3/23/1872 3/23/1872 54821 San Luis Obispo, California Tribune CA - San Luis Obispo 8/12/1876 8/12/1876 54824 Leadville Daily Herald CO - Leadville 11/18/1882 11/18/1882 54824 Connecticut Western News CT - Canaan 12/26/1895 12/26/1895 54825 Connecticut Western News CT - Canaan 7/9/1884 7/9/1884 56492 La Nueva Era CUB - Ponce 8/29/1898 8/29/1898 54825 Reporter DC - Washington, D.C. 1/22/1866 1/22/1866 54825 Reporter DC - Washington, D.C. 2/5/1866 2/5/1866 54825 Reporter DC - Washington, D.C. 2/22/1866 2/22/1866 54825 Reporter DC - Washington, D.C. 2/26/1866 2/26/1866 54825 Reporter DC - Washington, D.C. 3/5/1866 3/5/1866 54825 Reporter DC - Washington, D.C. -

Newspapers at the Hayes Presidential Library & Museums Compiled by John Ransom September 2016

Newspapers At the Hayes Presidential Library & Museums Compiled by John Ransom September 2016 CITY STATE NEWSPAPER TITLE FORMAT HOLDINGS ADA OH UNIVERSITY HERALD PA 1906-1913 AKRON OH AKRON BEACON JOURNAL PA 1919-1931 AKRON OH AKRON DAILY TELEGRAM PA 1 ISSUE, JULY 4, 1889 AKRON OH AKRON PRESS PA 1 ISSUE, HARDING'S DEATH AKRON OH AKRON TIMES PRESS PA 1919-1925, 3 ISSUES AKRON OH SUMMIT COUNTY BEACON PA 1884 & 1890 ALBANY GA KEYSTONE NEWS PA 1 ISSUE, APR. 1, 1932 ALEXANDRIA VA ALEXANDRIA GAZETTE / PA NOV. 29, 1877 VIRGINIA ADVERTISER ALLIANCE OH ALLIANCE REVIEW PA 1899-1938 ALLIANCE OH ALLIANCE REVIEW (STANDARD PA 1889 REVIEW) ALLIANCE OH ALLIANCE REVIEW (WEEKLY PA 1887 REVIEW) ALTON IL OBSERVER PA 1 ISSUE, DEC. 28, 1837 AMHERST NH FARMER'S CABINET PA SCATTERED, 1870, 1873-83, 1885, 1886, 1890 ANACOSTIA DC B. E. F. NEWS (BONUS PA 1 ISSUE, JULY 2, 1932 EXPEDITIONARY FORCES) ANN ARBOR MI ANN ARBOR REGISTER (W) PA 2 ISSUES, JULY 11, SEPT. 12, 1877 ASHTABULA OH ASHTABULA SENTINEL PA 1858, 5 ISSUES ASHVILLE OH PICKAWAY COUNTY NEWS PA 1 ISSUE, SEPT 24, 1925 ATHENS OH ATHENS COUNTY JOURNAL PA 1872, 2 ISSUES ATHENS OH ATHENS MESSENGER PA 1856-1899 ATHENS OH HOCKING VALLEY GAZETTE PA 1 ISSUE, AUG 14, 1840 AND ATHENS JOURNAL ATLANTA GA ATLANTA CONSTITUTION MF 1868-1900, 1912-1931, 1973, MISSING ISSUES ATLANTA GA ATLANTA JOURNAL MF 1883-1900, 1945, 1973, MISSING ISSUES ATTICA OH ATTICA HUB PA 1964-1985 AUGUSTA KY AUGUSTA HERALD PA 3 ISSUES, OCT. 17, 24, NOV. 7, 1827 CITY STATE NEWSPAPER TITLE FORMAT HOLDINGS BALTIMORE MD BALTIMORE GAZETTE PA 1 ISSUE, MAR. -

Kidnaping Charge May Not Be Made All Is Now Well With

'V OmiWLA'ilON AVBHA«il‘< o e tm * . iflfli Hght r*la toaiglit 5,442 ' «( ttw AuflR SHghHyMMi ~ I * f U Uuul a t l o a * : « ■ P a g * I t . ) PRICE THREE VOL. U V , NO. 46. MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, NOVEMBER 19, 1934. (TWELVE PMm y Damage Is Millions In Six Philippine Typhoons CATCH WRITER KIDNAPING CHARGE ALL IS NOW WELL OF500 TOISON WITH THE NATION, MAY NOT BE MADE PENJISSIVES ,t Report Has h That State’s PRESIDENT SAYS KIDNAPED CHILD Waterbnry Machinist Con- Attorney Has Not Enoigh REIDRNEDTOHOME fesses That He Is Anther President Deidares New Deal Evidence m the Darien GASPARRI RITES of Letters Sent in b st Is Progressiiig and Tint Case. Young Woman Hkcb-lfiker TO BE THURSDAY Five Years. ' the Coontry Is On the Way Had Taken Him Along Bridgeport, Nov. 19.—(AP)— State’s Attorney William H. Comley Waterbury, Conn., Nov. 19.—(AP) Funeral Date of Former Back to Prosperity. -Benjamin F. Brown. 42, of 344 la his investl||^tion Into the bead WidiHenSlielsHeld. to hand batUe and capture of three Farmington avenue, obviously un- Papal Secretary of State Warm Springs, Ga., Nov. 10.— their Rhode leland thugs la the home of aware of the seriousness of his of- Lexington, Ky., Nov. J9.—(AP)— (AP)—President Roosevelt, with Gustave U. Weathelm la Darien, Fri- fense as the author of some 500 day, baa pract|qally eliminated an Kidnaped foiur-year-old Jackie Gib- "poison pen" letters in the past five Set by Pontiff. the pronouncement that "all la weU" bons was restored to hie parents and that the New Deal Is progress- attempt at kidnaping. -

Classified Lists

LISTS Page Daily Papers . 1167 Papers having Rotogravure Photo- graphic Supplements . 1189 Sunday Papers (NotSunday Editions of Daily Papers) 1190 Monthly and Weekly Publications of General Circulation . 1191 Religious Publications . 1195 Agricultural Publications . 1205 Class and Trade Publications (Index) 1213 Secret Society Publications . 1283 Foreign Language Publications . 1287 Co-operative Lists . 1301 Alphabetical List . 1303 1167 DAILY NEWSPAPERS A LIST OF ALL DAILY NEWSPAPERS IN THE UNITED STATES ANDTHEIR POSSESSIONS AND THE DOMINION OF CANADA WHICH ARE PUBLISHEDCONTINUOUSLY THROUGHOUT THE YEAR, TOGETHER WITH THE POPULATION OF THEPLACES WHERE THEY ARE PUBLISHED, ACCORDING TO OUR LATEST INFORMATION. MORNING PAPERS APPEAR IN ROMAN TYPE. EVENING PAPERS IN ITALIC TYPE. DAILY PAPERS HAVING SUNDAY EDITIONS. WHETHER UNDER THESAME OR DIFFERENT TITLES, ARE MARKED WITH AN ASTERISK (5), THOSE HAVING WEEKLY, SEMI-WEEKLY TIONS. WITH PARALLELS (I). OR TRI-WEEKLY EDI- CIRCULATION FIGURES MARKED " (A.B.C.)" ARE THE TOTAL NET PAIDFIGURES OF SWORN STATEMENTS MADE FOR Tin,. AUDIT BUREAU OF CIRCULATIONS, AND COVER A PERIODOF SIX MONTHS, IN- CLUDING AT LEAST THREE MONTHS OF LAST YEAR. IN A VERY FEWCASES, WHERE NO MORE RECENT STATEMENT WAS RECEIVED, THEY REPRESENT THE TOTAL NETPAID CIRCULATION, AS REPORTED BY AN AUDITOR FROM THE AUDIT BUREAU OF CIRCULATIONS. Pop. ALABAMA Circ. Pop. Circ. Albany 12,500 .....Albany -Decatur Daily 3,200Mesa 4,000 Tribune 1.407 Anniston t Miami 9 000 Silver Belt I P. 0. Statement, 2,336 20,000 Star* P. 0. Statement. 6.514Nogales t 3,5/4. Herald 1,320 Birmingham ...........(A.B.C.), 23,560 Oasis *1 200,000 Sunday edit ion (A.B.C.), 20,795Phwnix t 25,000..Arizona Gazette" (A.B.