No One Knows You Are a Dog: Identity and Reputation in Virtual Worlds5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incommensurate Wor(L)Ds: Epistemic Rhetoric and Faceted Classification Of

Incommensurate Wor(l)ds: Epistemic Rhetoric and Faceted Classification of Communication Mechanics in Virtual Worlds by Sarah Smith-Robbins A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Rai Peterson Ball State University Muncie, IN March 28, 2011 Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................................... ii List of Tables ........................................................................................................................................... vi List of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... vii Abstract .................................................................................................................................................. ix Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. xi Chapter 1: Incommensurate Terms, Incommensurate Practices ............................................................... 1 Purpose of the Study ................................................................................................................................... 3 Significance of the Study ............................................................................................................................ -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,945,856 B2 Leahy Et Al

US007945856B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,945,856 B2 Leahy et al. (45) Date of Patent: May 17, 2011 (54) SYSTEMAND METHOD FOR ENABLING (56) References Cited USERS TO INTERACT IN A VIRTUAL SPACE U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS (75) Inventors: Dave Leahy, Oakland, CA (US); Judith 4.414,621 A 11/1983 Bown et al. Challinger, Santa Cruz, CA (US); B. 4,441,162 A 4, 1984 Lillie 4493,021 A 1/1985 Agrawal et al. Thomas Adler, San Francisco, CA (US); 4,503,499 A 3, 1985 Mason et al. S. Mitra Ardon, San Francisco, CA 4,531,184 A 7/1985 Wigan et al. (US) 4,551,720 A 11/1985 Levin 4,555,781 A 1 1/1985 Baldry et al. (73) Assignee: Worlds.com, Inc., Brookline, MA (US) (Continued) (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS patent is extended or adjusted under 35 CA 2242626 C 10, 2002 U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. (Continued) (21) Appl. No.: 12/353,218 OTHER PUBLICATIONS Andrew Reese et al., Kesami Air Warrior, http://www. (22) Filed: Jan. 13, 2009 atarimagazines.com/startv3n2/kesamiwarrior.html, Jan. 12, 2009. (Under 37 CFR 1.47) (Continued) (65) Prior Publication Data Primary Examiner — Kevin M Nguyen US 2009/0228.809 A1 Sep. 10, 2009 (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm — Anatoly S. Weiser, Esq.; Acuity Law Group Related U.S. Application Data (57) ABSTRACT (63) Continuation of application No. 1 1/591.878, filed on The present invention provides a highly scalable architecture Nov. -

Faculty Research Working Papers Series

Faculty Research Working Papers Series Napster's Second Life? - The Regulatory Challenges of Virtual Worlds Viktor Mayer-Schönberger and John Crowley September 2005 RWP05-052 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Napster’s Second Life? The Regulatory Challenges of Virtual Worlds+ Viktor Mayer-Schönberger* & John Crowley‡ Imagine a world with millions of people communicating and transacting. Imagine a world just like ours except that is it made entirely of bits, not atoms. Ten years ago, John Perry Barlow imagined such a radical world – cyberspace.1 He saw people interacting without the constraints of national rules. They would be independent from regulatory fiat and unbound by the mandates of Washington, Paris, London, Berlin or Beijing. His vision relied on information traveling a global network at lightning speed, with content living off server farms in nations with little regulation, weak enforcement, or both. In this world of global regulatory arbitrage2, organizations could relocate their servers to jurisdictional safe havens overnight. 3 They might pop up in exotic places like Aruba4 or + We thank Urs Gasser, Raph Koster, David Lazer, Beth Noveck, Cory Ondrejka, and John Palfrey, who have read the manuscript and provided most valuable feedback. We gratefully acknowledge the research assistance of Malte Ziewitz. * Associate Professor of Public Policy, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. ‡ Technologist and freelance consultant for the John F. -

The State of Play

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 49 Issue 1 State of Play Article 1 January 2005 The State of Play Beth Simone Noveck New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Gaming Law Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Beth S. Noveck, The State of Play, 49 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2004-2005). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. \\server05\productn\N\NLR\49-1\NLR116.txt unknown Seq: 1 8-DEC-04 9:59 THE STATE OF PLAY BETH SIMONE NOVECK* Before the World Wide Web, science fiction writer Neal Ste- phenson conceived of the Metaverse,1 the first virtual world. The imaginary Metaverse is the model — the city on a hill — that pro- grammers have been attempting to recreate for the “real” virtual world. In Stephenson’s vision, the Metaverse was not just a place for play. His Dickensian main character, Hiro Protagonist, plugs into a virtual office where he interacts with other characters as well as with artificial intelligence daemons.2 We are just beginning to realize Stephenson’s fantasy with vir- tual (sometimes called digital or synthetic) worlds that are currently used for play and social interaction but soon will be widely adopted as spaces for research,3 education,4 job recruiting,5 and work life.6 * Associate Professor and Director, Institute for Information Law and Policy, New York Law School; J.D. -

Virtual Worlds As Comparative Law

VIRTUAL WORLDS AS COMPARATIVE LAW JAMES GRiMMELMANN* I. INTRODUCTION One way of talking about virtual worlds' and law is to talk about the laws that might be applied to such worlds. This was the approach taken by many presenters at the State of Play confer- ence. 2 In various combinations, they discussed possible sources of legal control over virtual world game spaces and reasons to support or oppose such legal control. I intend to do something different. For purposes of this Arti- cle, I would like to take seriously the claims of virtual world games to be genuinely new societies, at least for awhile. Societies have laws, so why should virtual societies be any different? My topic, then, will not be the law of virtual worlds, but rather law in virtual worlds. If lawyers can learn from studying the legal systems of com- mon law and civil law countries, 3 perhaps we can also learn from studying the legal systems of virtual law worlds. In some cases, these legal systems track our own surprisingly well. In other cases, the contrasts are striking. Both the similarities * J.D. candidate, Yale Law School, 2005. The author would like to thank Amy Chua, Jack Balkin, Beth Noveck, the attendees at the State of Play conference, and those who provided comments on earlier versions of this paper. 1. Following Dan Hunter & F. Gregory Lastowka, The Laws of the Virtual Worlds, 92 CAL. L. REV. 1 (2004). I will use the term "virtual worlds" to describe these spaces. Like them, I am mostly concerned with large multiplayer online games, and will some- times refer simply to "games" when the meaning is clear from context. -

The Laws of the Virtual Worlds

California Law Review VOL. 92 JANUARY 2004 No. 1 Copyright © 2004 by California Law Review, Inc., a California Nonprofit Corporation The Laws of the Virtual Worlds F. Gregory Lastowkat & Dan Hunterl TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................3 A . V irtual W orlds ...........................................................................4 B. On the Real and the Virtual .......................................................7 I. A Virtual-World Primer ..................................................................14 A . W riting the W orld ....................................................................14 B. Drawing the World ..................................................................21 II. V irtual Properties ..........................................................................29 A. The Existence of Property in Virtual Worlds ...........................30 B. Early Conceptions of Virtual Property .....................................34 C. The Descriptive Account of Virtual Property .......................... 37 1. Metaphysical Problems ....................................................40 2. Temporal Problems ...........................................................42 D. The Normative Account of Virtual Property ............................43 1. Utilitarian Theories of Virtual Property ............................44 2. Lockean Theories of Virtual Property ...............................46 3. Personality Theories of Virtual Property ............................48 -

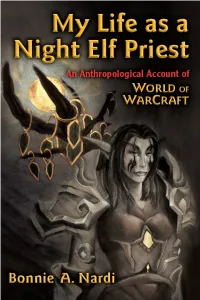

My Life As a Night Elf Priest Technologies of the Imagination New Media in Everyday Life Ellen Seiter and Mimi Ito, Series Editors

My Life as a Night Elf Priest technologies of the imagination new media in everyday life Ellen Seiter and Mimi Ito, Series Editors This book series showcases the best ethnographic research today on engagement with digital and convergent media. Taking up in-depth portraits of different aspects of living and growing up in a media-saturated era, the series takes an innovative approach to the genre of the ethnographic monograph. Through detailed case studies, the books explore practices at the forefront of media change through vivid description analyzed in relation to social, cultural, and historical context. New media practice is embedded in the routines, rituals, and institutions—both public and domes- tic—of everyday life. The books portray both average and exceptional practices but all grounded in a descriptive frame that renders even exotic practices understandable. Rather than taking media content or technology as determining, the books focus on the productive dimensions of everyday media practice, particularly of children and youth. The emphasis is on how specific communities make meanings in their engagement with convergent media in the context of everyday life, focus- ing on how media is a site of agency rather than passivity. This ethnographic approach means that the subject matter is accessible and engaging for a curious layperson, as well as providing rich empirical material for an interdisciplinary scholarly community examining new media. Ellen Seiter is Professor of Critical Studies and Stephen K. Nenno Chair in Television Studies, School of Cinematic Arts, University of Southern California. Her many publications include The Internet Playground: Children’s Access, Entertainment, and Mis-Education; Television and New Media Audiences; and Sold Separately: Children and Parents in Consumer Culture. -

7 Multi-Player Online Role-Playing Games

7 Multi-Player Online Role-Playing Games Mark Chen; Riley Leary; Jon Peterson; David Simkins This chapter describes multiplayer online role-playing games (MORPGs) where players participate through networked connections to collectively build a narrative or experience with a game that persists independent of who is logged in. We discuss two main traditions of these games (see Chapter 8 for an emerging tradition): 1. Multi-User Dungeons (MUDs), and 2. Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games (MMORPGs). MUDs and MMORPGs generally allow for a “massive” amount of players—sometimes hundreds, thousands, or tens of thousands of players who simultaneously engage in the same game. Most MUDs and MMORPGs feature worlds where players log in at any time to visit, providing players with a persistent world independent of who is logged in. A variety of agents are at play shaping the multiplayer online RPG form. Creators have introduced novel game systems or narratives while dealing with the affordances of what everyone agrees is an RPG, but creators are also constrained by the technologies of their time rather than inherent limitations in RPGs. There also exists a parallel history in non-digital RPGs and computer role-playing games (CRPGs) that influence the online games. Thus the evolution of MORPGs is not channeled through just one tradition. Thankfully, first-hand accounts of the history of the multiplayer online RPG industry (Bartle, 2010) and first-hand accounts of design and management decisions for specific games (e.g. Morningstar & Farmer, 1991; Curtis, 1996; Mulligan & Patrovsky, 2003) exist. One thing these accounts lack is scrutiny from scholars across multiple disciplines, studying specific player phenomena in online gaming, so this chapter complements the historical timeline with notable scholarly research on player behavior and community engagement. -

Vishnu and the Videogame: the Videogame Avatar and Hindu Philosophy

Vishnu and the Videogame: The Videogame Avatar and Hindu Philosophy Dr Souvik Mukherjee, IIT Delhi In 1986, Chip Morningstar, designer of the videogame Habitat , tied the ‘ Sanskrit term “ avatar ” to [one’s] real-time presence in an online world’ (Global Neighbourhood 2011). Soon after, the novelist Neal Stephenson popularized this usage in Snow Crash (1992) and in little over a decade, the word has gained phenomenal currency in Game Studies, discussions of gameplay, virtual reality, social networking and even in a blockbuster film. This, arguably, is more popular than the original Sanskrit usage. The concept of the avatar is the key point of departure for analyses of in-game identity and involvement. What relationship players have with their avatars has always been a moot question for Games Studies scholars. There are, obviously, extremes such as the avatar in James Cameron’s film where the protagonist’s consciousness seamlessly leaves his human body and wakes up into his avatar body. He is also able, at the end of the story, to sever ties forever with his real body and remain as his avatar. This seamlessness, although claimed as the characteristic experience of gameplay in early Game Studies theory, is too simplistic a description of the relationship between players and their online presence. Likewise, the description of the avatar as the ‘graphical representation of the user’s alter-ego’ is also extremely limited. In videogames, the player and the avatar can operate in complex ways such as when the player is simultaneously aware of and experiencing both her non-game and in-game identities. -

Virtual Justice: the New Laws of Online Worlds

VIRTUAL JUSTICE VIRTUAL JUSTICE the new laws of online worlds greg lastowka / new haven and london Portions of this work are adapted, with substantial revisions, from my prior writ- ings on virtual worlds, including “! e Laws of the Virtual Worlds” (with Dan Hunter), 92 California Law Review 1 (2004); “Virtual Crimes” (with Dan Hunter), 49 New York Law School Law Review 293 (2004); “Amateur- to- Amateur” (with Dan Hunter), 46 William & Mary Law Review 951 (2004); “Against Cyberproperty” (with Michael Carrier), 22 Berkeley Technology Law Journal 1485 (2007); “Decoding Cy- berproperty”, 40 Indiana Law Review 23 (2007); “User-Generated Content & Virtual Worlds,” 10 Vanderbilt J. Entertainment & Technology Law 893 (2008); “Planes of Power: EverQuest as Text, Game and Community,” 9 Game Studies 1 (2009); and “Rules of Play,” 4 Games & Culture 379 (2009). Copyright © 2010 by Greg Lastowka. All rights reserved. Subject to the exception immediately following, this book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying per- mitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. ! e author has made an online version of this work available under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 License. It can be accessed through the author’s Web site at http://www.chaihana.com/pers.html. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, busi- ness, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U. S. o# ce) or [email protected] (U. -

On Virtual Economies

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Castronova, Edward Working Paper On Virtual Economies CESifo Working Paper, No. 752 Provided in Cooperation with: Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Suggested Citation: Castronova, Edward (2002) : On Virtual Economies, CESifo Working Paper, No. 752, Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/76069 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu ON VIRTUAL ECONOMIES EDWARD CASTRONOVA CESIFO WORKING PAPER NO. 752 CATEGORY 9: INDUSTRIAL ORGANISATION JULY 2002 An electronic version of the paper may be downloaded • from the SSRN website: www.SSRN.com • from the CESifo website: www.CESifo.de CESifo Working Paper No. -

An Analysis in Aesthetic, Ethical, and Religious Movements Heather C

Free to Play: An Analysis in Aesthetic, Ethical, and Religious Movements Heather C. Ohaneson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Heather C. Ohaneson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Free to Play: An Analysis in Aesthetic, Ethical, and Religious Movements Heather C. Ohaneson In this dissertation, I investigate five forms of play with reference to freedom and constraint in order first to ascertain what relationship holds between play and liberty and then to see how the activity of play—and the attitude of playfulness—might contribute to a full and flourishing human life. To do so, I turn to an interdisciplinary set of figures, including Erik Erikson, Friedrich Schleiermacher, Blaise Pascal, Plato, and the contemporary scholars of improvisation Gary Peters and Danielle Goldman. It is my contention that the dialectical interrelation of liberty and limitation constitutes the essence of play and that the free engagement of constraints is a proper feature of eudaimonistic ethics. Instead of being regarded as a dispensable disposition, then, playfulness should be upheld alongside traditional virtues as a trait worthy of deliberate cultivation in adulthood. Seeking to enact the claim that boundaries give rise to expansive possibility, I provide a firm structure for this study and organize my analysis according to Søren Kierkegaard’s conceptions of the aesthetic, ethical, and religious spheres of existence. Liberty and limitation appear differently under each of these categories. Further, their forms change depending on whether they are viewed in light of children’s play, videogames, gambling, puppetry, or improvisation, the iterations of play and playful identity under consideration in this study.