IVAP Analysis Report April 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakistan Since 1947, When It Helped the Government Establish Refugee Camps for the Millions of People Displaced by the Partition

FACTS & FIGURES January – March 2012 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa / FATA The ICRC has been active in Pakistan since 1947, when it helped the government establish refugee camps for the millions of people displaced by the partition. Since 1980s, the ICRC remained in Pakistan, providing relief and medical assistance to the victims of the Afghan War. The ICRC has been permanently present in Peshawar since 1980 continuously helping vulnerable people. Distribution of food and other necessary items ICRC. Moreover, ICRC is also supporting a two-year Animal In cooperation with the Pakistan Red Crescent Society Husbandry In-Service Training Institute, Peshawar. (PRCS), the ICRC donated firewood and body soap to 138 internally displaced families residing in Risalpur Camp. Post distribution monitoring of the beneficiaires who Moreover, wheat flour (50 kg per household), blankets, received seeds, fertilizers and tools kits in DI Khan, Swat, cloth, mattresses, pillows and other items were also donated Buner and Malakand is continuously conducted to assist to five NGOs and community based organizations, PRCS more than 5,000 farmers in the area for improving overall branches in KP and FATA. A total of 2,000 affected families wheat production. The ICRC conducted monitoring of 1,673 from KP and FATA benefited from this distribution. vegetable growers in Barikot, Kabal and Madiyan farm service centers at the department of agriculture in Swat Production support district. Small business grants were provided to 13 people under the micro-economic initiatives program in Lower Dir (10) and Water and sanitation Swat (03) in January 2012. Second round verification of the Buner: The ICRC has completed Kalpani I and II water 254 income generated projects supported by the ICRC in supply schemes including changing of pumping machineries lower and upper Dir districts was conducted in March. -

Floods in Pakistan Pakistan Health Cluster Bulletin No 13 21 August 2010

Floods in Pakistan Pakistan Health Cluster Bulletin No 13 21 August 2010 Vaccination campaign at an IDP camp at Government Girls High School in Taluka Sehwan, Jamshoro district, Sindh province. • Number of reporting disease cases is increasing. Until 18 August, 204 040 of acute diarrhoea, 263 356 cases of skin diseases and 204 647 of acute respiratory have been reported in flood-affected provinces. More than 1.5 million patient consultations have been conducted in flood-affected provinces since 29 July. • Daily number of reported acute diarrhoea cases, monitored since 31 July is rising, particularly in Charsadda, Nowshera and Peshawar. • From 16-18 August, 6 new suspected acute diarrhoea alerts reported from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK). • WHO establishing diarrhoeal treatment centres in flood-affected districts with government and partner support. • Health Cluster to have access to UNHAS flights for delivery of medical items. • Health Cluster coordination active in 5 hubs - Islamabad, Peshawar, Multan, Sukkur, Quetta. • WHO delivers large shipment of medicines to Sukkur coordination hub on 20 August. • In first 3 days of emergency vaccination campaign launched in Peshawar and Charsadda on 16 August, 104 640 children under 5 years were vaccinated against polio. All aged over 6 months (92 269 children) also vaccinated against measles and received vitamin A capsules. • As of 21 August, 39% of the US$56.2 million requested to support the health response has been funded. • According to the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), more than 20 million people have been affected by the floods. Almost 1500 people have been reported killed and more than 2000 injured, while around 1 million are left homeless. -

Annual Development Programme

ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 16 - PROGRAMME 2015 PROGRAMME DEVELOPMENT ANNUAL GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT JUNE, 2015 www.khyberpakhtunkhwa.gov.pk FINAL ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2015-16 GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT http://www.khyberpakhtunkhwa.gov.pk Annual Development Programme 2015-16 Table of Contents S.No. Sector/Sub Sector Page No. 1 Abstract-I i 2 Abstract-II ii 3 Abstract-III iii 4 Abstract-IV iv-vi 5 Abstract-V vii 6 Abstract-VI viii 7 Abstract-VII ix 8 Abstract-VIII x-xii 9 Agriculture 1-21 10 Auqaf, Hajj 22-25 11 Board of Revenue 26-27 12 Building 28-34 13 Districts ADP 35-35 14 DWSS 36-50 15 E&SE 51-60 16 Energy & Power 61-67 17 Environment 68-69 18 Excise, Taxation & NC 70-71 19 Finance 72-74 20 Food 75-76 21 Forestry 77-86 22 Health 87-106 23 Higher Education 107-118 24 Home 119-128 25 Housing 129-130 26 Industries 131-141 27 Information 142-143 28 Labour 144-145 29 Law & Justice 146-151 30 Local Government 152-159 31 Mines & Minerals 160-162 32 Multi Sectoral Dev. 163-171 33 Population Welfare 172-173 34 Relief and Rehab. 174-177 35 Roads 178-232 36 Social Welfare 233-238 37 Special Initiatives 239-240 38 Sports, Tourism 241-252 39 ST&IT 253-258 40 Transport 259-260 41 Water 261-289 Abstract-I Annual Development Programme 2015-16 Programme-wise summary (Million Rs.) S.# Programme # of Projects Cost Allocation %age 1 ADP 1553 589965 142000 81.2 Counterpart* 54 19097 1953 1.4 Ongoing 873 398162 74361 52.4 New 623 142431 35412 24.9 Devolved ADP 3 30274 30274 21.3 2 Foreign Aid* * 148170 32884 18.8 Grand total 1553 738135 174884 100.0 Sector-wise Throwforward (Million Rs.) S.# Sector Local Cost Exp. -

The Haqqani Network in Kurram the Regional Implications of a Growing Insurgency

May 2011 The haQQani NetworK in KURR AM THE REGIONAL IMPLICATIONS OF A GROWING INSURGENCY Jeffrey Dressler & Reza Jan All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ©2011 by the Institute for the Study of War and AEI’s Critical Threats Project Cover image courtesy of Dr. Mohammad Taqi. the haqqani network in kurram The Regional Implications of a Growing Insurgency Jeffrey Dressler & Reza Jan A Report by the Institute for the Study of War and AEI’s Critical Threats Project ACKNOWLEDGEMENts This report would not have been possible without the help and hard work of numerous individuals. The authors would like to thank Alex Della Rocchetta and David Witter for their diligent research and critical support in the production of the report, Maggie Rackl for her patience and technical skill with graphics and design, and Marisa Sullivan and Maseh Zarif for their keen insight and editorial assistance. The authors would also like to thank Kim and Fred Kagan for their necessary inspiration and guidance. As always, credit belongs to many, but the contents of this report represent the views of the authors alone. taBLE OF CONTENts Introduction.....................................................................................1 Brief History of Kurram Agency............................................................1 The Mujahideen Years & Operation Enduring Freedom .............................. 2 Surge of Sectarianism in Kurram ...........................................................4 North Waziristan & The Search for New Sanctuary.....................................7 -

Afghan Refugees Camp Population in KP March, 2018

SOLUTION STRATEGY UNIT COMMISSIONERATE AFGHAN REFUGEES KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA, PESHAWAR March, 2018 CAMP WISE AFGHAN REFUGEES POLULATION IN KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA S/No Name of District Name of Admn Camp Cluster Camps Population FAM IND 1 Kababian 2,3 764 4194 Kababian Michani/Warsak 30 196 2 Badaber 2840 14438 3 Khazana Khazana / Wahid Gari 921 4434 4 Naguman 410 2437 5 Khurasan 376 2259 Mere Kachori, Zandai 541 3400 6 Peshawar Mera Kachori Baghbanan 2149 9770 7 Shamshatoo Gul Badin, Old/ Molvi Khalid 3631 18817 Sub-Total Peshawar 11662 59945 8 Utmanzai 535 3268 Munda - I-II 1007 5099 9 Munda Ekka Gund 363 1471 10 Hajizai 501 2880 Sub-total Charsadda 2406 12718 Charsadda Akora Khattak Akora new, Hawai, 4509 22606 11 Kheshki 210 1710 12 Khairabad Khairabad 1926 9239 13 Turkaman Turkaman/Jalozai 410 2820 Nowshera Sub-Total Nowshera 7055 36375 14 Lakhti Banda 294 2085 Kata Kani 1000 6007 15 Kata Kani Kotki 297 2054 Kahi-I-II 1020 7937 16 Kahi Doaba 46 1165 17 Darsamand I-II 1640 10916 Hangu 18 Thall Thall-I-II 1270 12035 Sub-Total Hangu 5567 42199 19 Gamkol Gamkol -I-II-III 4932 30713 Oblen 1338 8081 20 Oblen Jarma 375 1067 Ghulam Banda 1021 6208 21 Ghulam Banda Shin Dhand 236 1426 22 Chichana 611 3901 Sub-Total Kohat 8513 51396 23 Jalala Jalala 1,2,3 1496 8187 Baghicha 481 2743 24 Baghicha Kagan 249 1352 Mardan Sub-Total Mardan 2226 12282 25 Barakai 2013 12606 Barakai Fazal 810 2731 26 Gandaf 2823 18226 Swabi Sub-Total Swabi 5646 33563 27 Zangal Patai 696 4125 Sub-Total Malakand 696 4125 Malakand Kohat Koga 1680 7972 28 Buner Sub-Total Buner 1680 -

HEALTH CLUSTER PAKISTAN Crisis in NWFP WEEKLY BULLETIN No

HEALTH CLUSTER PAKISTAN Crisis in NWFP WEEKLY BULLETIN No 12 9 September 2009 HIGHLIGHTS • The IDP return process continues. Health Cluster partners are moving forward with health interventions in the districts of Swat, Buner, Lower Dir and Upper Dir while continuing to support IDPs who remain in the camps. To date, a total of 235 159 families have returned to their respective districts. (Source: PDMA/PaRRSA.) • The latest data from the National Database Registration Authority (NADRA) show there has been an influx of returnees in Waziristan. A total of 17 375 families, including 8281 in D.I. Khan District and 2756 in Tank District, have registered. Maternal, neonatal and and child health remains a priority among health interventions in NWFP • An assessment of health facilities in D.I. Khan was completed on 28 August. The report is being finalized and will be shared shortly. An assessment of health facilities in Swat district will begin on 13 September. • Between 22 and 28 August, a total of 69 892 consultations were reported from 226 disease surveillance sentinel sites in NWFP. This represents a 7% decrease compared to the number of consultations registered the previous week. • Seventeen DEWS sites reported 546 antenatal visits between 22 and 28 August. Data from UNFPA’s seven maternal, neonatal and child health (MNCH) care service delivery points in Lower Dir, Nowshera, Charsadda and Mardan districts showed an overall 16% increase in patient consultations in government and in-camp health facilities. However, postnatal consultations decreased from 48 to 35, and deliveries dropped from 18 to 10 at MNCH clinics. -

Guía Mundial De Oración (GMO). Noviembre 2014 Titulares: Los

Guía Mundial de Oración (GMO). Noviembre 2014 Titulares: Los inconquistables Pashtun! • 1-3 De un ciego que llevó a los Pashtunes Fuera de la Oscuridad • 5 Sobre todo Hospitalidad! • 8 Estilo de Resolución de Conflictos Pashtun • 23 Personas Mohmund: Poetas que alaban a Dios • 24 Estaría de acuerdo con los talibanes sobre esto! Queridos Amigos de oración, Yo soy un inglés, irlandés, y de descendencia sueca. Hace mil ochocientos años, mis antepasados irlandeses eran cazadores de cabezas que bebían la sangre de los cráneos de sus víctimas. Hace mil años mis antepasados vikingos eran guerreros que eran tan crueles cuando allanaban y destruían los pueblos desprotegidos, que hicieron la Edad Media mucho más oscura. Eventualmente la luz del evangelio hizo que muchos grupos de personas se convirtieran a Cristo, el único que es la Luz del Mundo. Su cultura ha cambiado, y comenzaron a vivir más por las enseñanzas de Jesús y menos por los caminos del mundo. La historia humana nos enseña que sin Cristo la humanidad puede ser increíblemente cruel con otros. Este mes vamos a estar orando por los Pashtunes. Puede parecer que estamos juzgando estas tribus afganas y pakistaníes. Pero debemos recordar que sin la obra transformadora del Espíritu Santo, no seríamos diferentes de lo que ellos son. Los Pashtunes tienen un código cultural de honor llamado Pashtunwali, lo que pone un cierto equilibrio de moderación en su conducta, pero también los estimula a mayores actos de violencia y venganza. Por esta razón, no sólo vamos a orar por tribus Pashtunes específicas, sino también por aspectos del código de honor Pashtunwali y otras dinámicas culturales que pueden mantener a los Pashtunes haciendo lo que Dios quiere que hagan. -

Dera Ismail Khan Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (DERA ISMAIL KHAN DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH DERA ISMAIL KHAN DISTRICT 1,627,132 201,301 DARABAN TEHSIL 123,933 15,007 DARABAN QH 78,938 9591 DARABAN PC 26,932 3135 DARABAN 26,932 3135 058010101 4,721 405 058010102 694 71 058010103 1,777 181 058010104 1,893 210 058010105 2,682 360 058010106 1,161 141 058010107 1,113 135 058010108 471 151 058010109 1,352 163 058010110 1,857 225 058010111 3,636 425 058010112 2,619 281 058010113 2,956 387 GANDI ASHAK PC 6,942 873 DHAUL KA JADID 1,494 196 058010206 1,494 196 GANDI ASHAK 4,165 523 058010201 2,272 267 058010202 696 97 058010203 433 58 058010204 764 101 MOCHI WAL 1,283 154 058010205 1,283 154 GANDI UMAR KHAN PC 7,246 966 GANDI UMAR KHAN 6,972 930 058010401 1,579 229 058010402 1,710 237 058010403 1,792 226 058010404 1,891 238 KHIARA BASHARAT 105 18 058010405 105 18 KHIARA FATEH MOHAMMAD 169 18 058010406 169 18 GARA MAHMOOD PURDIL PC 6,414 771 GARA KHAN WALA 450 56 058010505 450 56 GARA MAHMOOD PURDIL 1,940 230 058010502 1,940 230 KOT ISA KHAN 2,806 341 058010503 1,270 157 Page 1 of 36 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (DERA ISMAIL KHAN DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 058010504 1,536 184 MASTAN 1,218 144 058010501 1,218 144 KIKRI PC 6,058 729 GANDI ISAB 952 118 058010606 952 118 GARA MIR ALAM 996 117 058010604 996 117 GARA MURID SHAH 363 57 058010605 363 57 KIKRI 2,833 330 058010601 1,241 150 058010602 1,592 180 KOT SHAH NAWAZ 914 107 058010603 914 -

Pakistan National Nutrition Cluster Preparedness and Response Plan

National Nutrition Cluster 3 July 2013 Pakistan National Nutrition Cluster Preparedness and Response Plan The National Nutrition Cluster Preparedness and Response Plan is a common framework to guide the actions of all partners in the nutrition sector in the event of a disaster. It does not replace the need for planning by individual agencies in relation to their mandate and responsibilities within clusters, but provides focus and coherence to the various levels of planning that are required to respond effectively. It is envisioned that the Preparedness and Response Plan is a flexible and dynamic document that will be updated based on lessons learnt in future emergency responses. Each Provincial Nutrition Cluster will develop a Provincial Nutrition Cluster Preparedness and Response Plan, in cooperation with the Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA) and the Department of Health (DoH). The Provincial Plans are stand-alone documents, however are linked and consistent with the National Plan. 1. Background The 2011 Pakistan National Nutrition Survey confirmed that Pakistan’s population still suffers from high rates of malnutrition and that the situation has not improved for several decades. Two out of every five (44 percent) of children under five are stunted, 32 percent are underweight and 15 percent suffer from acute malnutrition.1 Maternal malnutrition is also a significant problem; 15 percent of women of reproductive age have chronic energy deficiency. Women and children in Pakistan also suffer from some of the world’s highest levels of vitamin and mineral deficiencies. The malnutrition rates are very high by global standards and are much higher than Pakistan’s level of economic development should warrant. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of Local Governments District Bannu Audit

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF LOCAL GOVERNMENTS DISTRICT BANNU AUDIT YEAR 2018-19 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviation…………………………………………..…………………..………i Preface ................................................................................................................. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................. iii SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS ................................................................... vii I: Audit Work Statistics ...................................................................................... vii II: Audit observations Classified by Categories .................................................. vii III: Outcome Statistics ...................................................................................... viii IV: Table of Irregularities pointed out ................................................................. ix V: Cost Benefit Ratio .......................................................................................... ix CHAPTER-1 ....................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Local Governments Bannu ............................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) .................... 5 1.1.3 Comments on the status of compliance with DAC / TAC Directives ..... 7 1.2 DISTRICT -

25 January 2013)

1213297 [2013] RRTA 91 (25 January 2013) DECISION RECORD RRT CASE NUMBER: 1213297 DIAC REFERENCE(S): CLF2012/141724 COUNTRY OF REFERENCE: Pakistan TRIBUNAL MEMBER: Amanda Goodier DATE: 25 January 2013 PLACE OF DECISION: Perth DECISION: The Tribunal remits the matter for reconsideration with the direction that the applicant satisfies s.36(2)(a) of the Migration Act. STATEMENT OF DECISION AND REASONS APPLICATION FOR REVIEW 1. This is an application for review of a decision made by a delegate of the Minister for Immigration to refuse to grant the applicant a Protection (Class XA) visa under s.65 of the Migration Act 1958 (the Act). 2. The applicant who claims to be a citizen of Pakistan applied to the Department of Immigration for the visa on [date deleted under s.431(2) of the Migration Act 1958 as this information may identify the applicant] June 2012. 3. The delegate refused to grant the visa [in] August 2012, and the applicant applied to the Tribunal for review of that decision. RELEVANT LAW 4. Under s.65(1) a visa may be granted only if the decision maker is satisfied that the prescribed criteria for the visa have been satisfied. The criteria for a protection visa are set out in s.36 of the Act and Part 866 of Schedule 2 to the Migration Regulations 1994 (the Regulations). An applicant for the visa must meet one of the alternative criteria in s.36(2)(a), (aa), (b), or (c). That is, the applicant is either a person in respect of whom Australia has protection obligations under the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees as amended by the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees (together, the Refugees Convention, or the Convention), or on other ‘complementary protection’ grounds, or is a member of the same family unit as a person in respect of whom Australia has protection obligations under s.36(2) and that person holds a protection visa. -

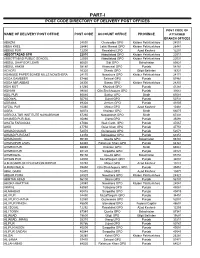

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151