Developing a Cybervetting Strategy for Law Enforcement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DMU Handout for Presentations 3 5 12

Practice Marketing Solutions Dental Marketing Universe provides you with a wide array of proven marketing solutions designed to help your practice grow. Whether your practice is looking for a simple website, referral marketing, team training or a direct to consumer marketing campaign, we have the right solutions for you. A comprehensive program for building your speciality practice referrals. The ReferralZone delivers patients to the general dentist directly from the speciality practice. What better way ReferralZone™ to build referrals! Sending patients to your referrals couldn’t be easier! DMU manages the entire program so you and your referring practices can do what you do best, practice dentistry! Benefits – Builds loyalty with your referring practices and delivers patients directly to the general dentist. The next generation website solution for dental professionals who want the ultimate Web presence for their practice. In addition to spectacular site styles, each website is powered by an exclusive Web Engine technology that provides the dentist with unique ability to control ProSites™ virtually every aspect of their website, without any knowledge of programming or web design skills. Stop paying web designers to make changes to your website. Search Engine Optimized (SEO), complete editing control. Get your website up and running in less than a day! Ask about our zero interest financing! Benefits – Helps inform, educate and deliver new patients. You may have a great web presence but when potential patients visit your website on a mobile device they may find it difficult to navigate your site. AT&T research indicates that over 72% of these people leave your website never to return. -

List of Search Engines Listed by Types of Searches

List of Search Engines Listed by Types of Searches - © 09-14-2014 - images removed Copyright - Professional Web Services Internet Marketing SEO Business Solutions - http://pwebs.net - All Rights Reserved List of Search Engines Listed by Types of Searches by ProWebs - Article last updated on: Saturday, July 28, 2012 http://pwebs.net/2011/04/search-engines-list/ To view images click link above. This page posting has been updated with the addition of some of the newer search engines. The original search engine page was dealing mainly with B2B and B2C search. However, with today's broad based Internet activity, and how it relates to various aspects of business usage, personal searches, and even internal intranet enterprise searches, we wanted to highlight some of the different search market segments. This list of the various search engines, is posted here mainly for research and education purposes. We felt it is nice to be able to reference and have links to some of the different search engines all in one place. While the list below does not cover each and every search engine online, it does provide a broad list of most of the major search companies that are available. Also note that some of the search engine links have been redirected to other sites due to search buyouts, mergers, and acquisitions with other companies, along with changes with the search engines themselves (for example: search companies have changed brand names, different URLs, and links). You will also notice that some of the search websites go back a number of years. If you would like to read more about the details of any particular search engine, take a look at the Wikipedia Search Engines List article, and follow the links to each specific search engine for a descriptive overview. -

Web Search Engine

Web Search Engine Bosubabu Sambana, MCA, M.Tech Assistant Professor, Dept of Computer Science & Engineering, Simhadhri Engineering College, Visakhapatnam, AP-531001, India. Abstract: This hypertext pool is dynamically changing due to this reason it is more difficult to find useful The World Wide Web (WWW) allows people to share information.In 1995, when the number of “usefully information or data from the large database searchable” Web pages was a few tens of millions, it repositories globally. We need to search the was widely believed that “indexing the whole of the information with specialized tools known generically Web” was already impractical or would soon become as search engines. There are many search engines so due to its exponential growth. A little more than a available today, where retrieving meaningful decade later, the GYM search engines—Google, information is difficult. However to overcome this problem of retrieving meaningful information Yahoo!, and Microsoft—are indexing almost a intelligently in common search engines, semantic thousand times as much data and between them web technologies are playing a major role. In this providing reliable sub second responses to around a paper we present a different implementation of billion queries a day in a plethora of languages. If this semantic search engine and the role of semantic were not enough, the major engines now provide much relatedness to provide relevant results. The concept higher quality answers. of Semantic Relatedness is connected with Wordnet which is a lexical database of words. We also For most searchers, these engines do a better job of made use of TF-IDF algorithm to calculate word ranking and presenting results, respond more quickly frequency in each and every webpage and to changes in interesting content, and more effectively Keyword Extraction in order to extract only useful eliminate dead links, duplicate pages, and off-topic keywords from a huge set of words. -

Local Online Directories

MARKETINGLOCAL BUSINESS The Marketing Guide for Local Businesses Owners November 2014 How To Get Local Online Your Local Directories: Business Why it is Critical your Noticed on Business is Listed! Black Friday • The Ultimate List of Local Online Directories 10 Free Tools to Test Your Website’s Speed Facebook Bans Fan-Gating: 3 Alternatives Usability 101: Tips for Improving the Visitor Experience of Your Website Infographic: Local Search Ranking Factors FREE! Proudly Provided by LMS Solutions, Inc. MARKETINGLOCAL BUSINESS Inside This Each November we’re reminded to pause and Month’s Issue think about those things that we are truly thankful for. 4 Marketing Calendar Aside from the traditonal things, such as family and health, we have many things to be thankful 5 Facebook Bans Fan-Gating: for, and we don’t take them for granted. 3 Alternatives We’re thankful for our valued clients! 7 Building Better Business Curb Appeal We’re thankful that you find value in this magazine! 8 Curb Appeal Checklist We’re thankful for the number of client referalls we receive! 9 How To Get Your Local Business Noticed on Black We’re thankful that the services we provide help Friday our clients grow their business. Time To Start Planning We’re thankful for you! If you aren’t yet one of 12 Holiday Gifts: our clients, we look forward to the day we can count you as part of our business family. But what should you give? If you have any comments about this issue or 14 Usability 101: Tips for would like us to help you with your marketing Improving the Visitor please do not hesitate to contact us. -

What You Need to Know About Google Local Edited V4

Google Local? What Every Lawyer Needs To Know to Dominate It’s The New Yellow Pages! by Tom Foster and George Murphy Why Should You Care About Google Local? Understanding Google Local – The Basics What is Google Local and why do you care? First of all, recognize the importance that Google, the #1 search engine and fastest growing technology company ever, has placed on Google Local. Below is an example of a typical search for “DUI Attorney Richmond VA” Notice that “Local business results for dui attorney near Richmond, VA” are listed directly beneath “Sponsored Links” (Google Adwords) and before organic search results. Clicking on the red pushpin (annotated by letter in the map) will open Google Maps. Maps will provide directions and provide a GPS guide to the listed address. Google Local is considered by many to be the “new” Yellow Pages. As such, it is a very powerful marketing vehicle that all attorneys who are focusing on geo-location based practice areas (like my example) must take advantage of. Just for clarity sake, Google Local listings rely on the Google Maps GPS technology. 2 Why Should You Care About Google Local? It seems to be a mystery, no matter what service or product you’re offering, as to how to increase your rankings on Google Local searches. The devil is in the details and this is true for Google Local listing and placement as well. Whether you’re a local attorney, doctor, dentist, barbershop or retail store, higher rankings on the local Google search is just as important as your organic search engine rankings because of the increased online exposure that it offers as the first displayed results. -

Internet Marketing for Local Business

Internet Marketing For Local Business Internet Marketing For Local Business Edward Kundahl, Ph.D., M.B.A. BusinessCreator, Inc. www.BusinessCreatorPlus.com Internet Marketing For Local Business DEDICATION This book is dedicated to all the men, women, teens and children who aspire to live the entrepreneurial dream in a democratic environment. I give thanks to the technology era, while we further expose ourselves, we can leverage the Internet era to flourish the dream that the little guy can still make it. I dedicate my work, effort, direction, ideas and passion put forth in my work to and from my mom and dad. Internet Marketing For Local Business Forewords This book has come from several years’ worth of work and education and experience as a business owner. I opened my first small business-marketing agency in 2000, recognizing early on the advent of Google would change the face of how business is done on the Internet. Our industry of Internet marketing has become very confusing and cluttered with technology gurus, executives, spammers and newbies. This has made it very difficult for the local business owner to push their business through. Fortunately great companies like Google were built on something organic. Like the food you eat, organic is good. Word of mouth advertising is the best form of marketing, it’s organic, and it is natural. While Google is a massive company with dozens of amazing products, their foundation is search. You can’t buy organic results. Hence Google must give great results, make their users’ happy, or they won’t come back. -

By Content/Topic

Different search engines This is a list of Wikipedia articles about search engines, including web search engines, selection-based search engines, metasearch engines, desktop search tools, and web portals and vertical market websites that have a search facility for online databases. By content/topic General Baidu (Chinese, Japanese) Bing Blekko Google Sogou (Chinese) Soso.com (Chinese) Volunia Yahoo! Yandex (Russian) Yebol Yodao (Chinese) WireDoo P2P search engines FAROO Seeks (Open Source) YaCy (Free and fully decentralized) Metasearch engines See also: Metasearch engine Brainboost ChunkIt! Clusty DeeperWeb Dogpile Excite Harvester42 HotBot Info.com Ixquick Kayak LeapFish Mamma Metacrawler MetaLib Mobissimo Myriad Search SideStep WebCrawler Geographically limited scope Accoona, China/United States Alleba, Philippines Ansearch, Australia/United States/United Kingdom/New Zealand Biglobe, Japan Daum, Korea Goo, Japan Guruji.com, India Leit.is, Iceland Maktoob, Arab World Miner.hu, Hungary Najdi.si, Slovenia Naver, Korea Onkosh, Arab World Rambler, Russia Rediff, India SAPO, Portugal/Angola/Cabo Verde/Mozambique Search.ch, Switzerland Sesam, Norway, Sweden Seznam, Czech Republic Walla!, Israel Yandex, Russia Yehey!, Philippines ZipLocal, Canada/United States Accountancy IFACnet Business Business.com GenieKnows (United States and Canada) GlobalSpec Nexis (Lexis Nexis) Thomasnet (United States) Enterprise See also: Enterprise search AskMeNow: S3 - Semantic Search Solution Concept -

Web Search Engine

Web search engine A web search engine is designed to search for information on the World Wide Web and FTP servers. The search results are generally presented in a list of results and are often called hits. The information may consist of web pages, images, information and other types of files. Some search engines also mine data available in databases or open directories. Unlike Web directories, which are maintained by human editors, search engines operate algorithmically or are a mixture of algorithmic and human input. How web search engines work:- A search engine operates, in the following order 1. Web crawling 2. Indexing 3. Searching Web search engines work by storing information about many web pages, which they retrieve from the html itself. These pages are retrieved by a Web crawler (sometimes also known as a spider) — an automated Web browser which follows every link on the site. Exclusions can be made by the use ofrobots.txt. The contents of each page are then analyzed to determine how it should be indexed (for example, words are extracted from the titles, headings, or special fields called meta tags). Data about web pages are stored in an index database for use in later queries. A query can be a single word. The purpose of an index is to allow information to be found as quickly as possible. Some search engines, such as Google, store all or part of the source page (referred to as a cache) as well as information about the web pages, whereas others, such as AltaVista, store every word of every page they find. -

Dbpedia - a Linked Data Hub and Data Source for Web and Enterprise Applications

Conference Organization Programme Chairs Raoul-Sam Daruwala Cong Yu Programme Committee Gustavo Alonso Srikanta Bedathur Kevin Chang Isabel Drost Ariel Fuxman Lee Giles Sharad Goel Richard Hankins Jeffrey Korn Chris Mattmann Charles McCathieNevile Peter Mika Stelios Paparizos Eugene Shekita Jimeng Sun Jian Shuo Wang Ding Zhou Aoying Zhou Local Organization Table of Contents Creating Your Own Web-Deployed Street Map Using Open Source Software and Free Data :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 Christopher Adams, Tony Abou-Assaleh Query Portals :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 4 Sanjay Agrawal, Kaushik Chakrabarti, Surajit Chaudhuri, Venkatesh Ganti, Arnd Konig, Dong Xin A Semantic Web Ready Service Language for Large-Scale Earth Science Archives ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 Peter Baumann Silk ^aA Link Discovery Framework for the Web of Data ::::::::::::::: 10 Christian Bizer, Julius Volz, Georgi Kobilarov, Martin Gaedke Improving interaction via screen reader using ARIA: an example :::::::: 13 Marina Buzzi, Maria Claudia Buzzi, Barbara Leporini, Caterina Senette A REST Architecture for Social Disaster Management ::::::::::::::::: 16 Julio Camarero, Carlos A. Iglesias Integration at Web-Scale: Cazoodle's Agent Technology for Enabling Vertical Search ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 19 Kevin Chang, Govind Kabra, Quoc Le, Yuping Tseng The Future of Vertical Search Engines with Yahoo! Boss ::::::::::::::: 22 Ted DRAKE CentMail: Rate Limiting via Certified Micro-Donations -

Radio Frequency Identification Based Smart

ISSN (Online) 2394-2320 International Journal of Engineering Research in Computer Science and Engineering (IJERCSE) Vol 3, Issue 10, October 2016 History and Web Search Engines Works [1]Saurabh Kumar, [2] Maneesh Kumar, [3] Vipul Agarwal M .Tech Scholar, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Dr. A.P.J Abdul Kalam Technical University, Lucknow (U.P), Abstract: -- A web search engine is a software system that is designed to search for information on the World Wide Web. The search results are generally presented in a line of results often referred to as search engine results pages(SERPs). The information may be a mix of web pages, images, and other types of files. Some search engines also mine data available in databases or open directories. Unlike web directories, which are maintained only by human editors, search engines also maintain real- time information by running an algorithm on a web crawler. I. INTRODUCTION Lycos Active Search engine is a web software program or Infoseek Inactive web based script available over the Internet that searches documents and files for keywords and returns the list of results containing those keywords. Today, there are 1995 AltaVista Inactive, redirected to Yahoo! numbers of different search engines available on the Internet, each with their own techniques and specialties. Daum Active Search Engine Optimization is a technique to improve visibility of a website in search engine. Magellan Inactive II. HISTORY Excite Active Timeline (full list) SAPO Active Year Engine Current status Yahoo! Active, -

Search Engine: a Survey

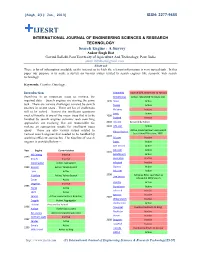

[Singh , 2(1): Jan., 2013] ISSN: 2277 -9655 IJESRT INTERNATIONAL JOURNA L OF ENGINEERING SCI ENCES & RESEARCH TECHNOLOGY Search Engine : A Survey Ankur Singh Bist Govind Ballabh P ant University of Agriculture And Technology, Pant, India [email protected] Abstract There is lot of information available on the internet so to fetch the relevant information is very typical task . In this paper our purpose is to make a survey on various issues related to search engines li ke semantic web search technology. Keywords: Crawler, Ontology .. Introduction AlltheWeb Inactive (URL redirected to Yahoo!) Searching is an important issue to retrieve the GenieKnows Active, rebranded Yellowee.com required data . Search engines are serving the same 1999 Naver Active task . There are various challenges covered by search Teoma Active engines in recent years . There are lot of challenges Viv isimo Inactive still to be solved . Answer the intelligent questions Baidu Active most efficiently is one of the major issue that is to be 2000 handled by search engines semantic web searching Exalead Inactive approaches are evolving that are responsible for 2002 Inktomi Acquired by Yahoo! making an appropriate results for intelligent input 2003 Info.com Active query . There are also various issues related to Active, Launched own web search Yahoo! Search vertical search engines that needed to be handled by (see Yahoo! Directory, 1995) 2004 applying efficient approaches .The timeline of search A9.com Inactive engines is provided below:-- Sogou Active AOL Search Active -

Search Engines: the Propellers of Information Diffusion Jagandeep Singh

ISSN 2229-5984 Search Engines: The Propellers of Information Diffusion Jagandeep Singh ABSTRACT Assistant Professor Gone are the days when one used to grope in the dark for a relevant piece of UIAMS, information. In the present day world, one is inundated with information, Panjab University, Chandigarh. courtesy the World Wide Web. This surfeit of information brings in its wake, a different challenge; that of information overload. The search engines, led by Google, enable surfers to dig into this enormous set of information and fish out the requisite data. To that extent these search engines are a sine qua non and the flag bearers of information dissemination. The present paper is a modest attempt to understand the functioning of these search engines. The Correspondence to: paper, by enlisting the various search engines and their purpose, tries to Dr. Jagandeep Singh highlight the range of options available to surfers. Finally the paper attempts [email protected] to envisage as to what the future would look like in the terrain of Internet search. Introduction How the Search Engine Works Communication and data dissemination in the present To a layman, Google is, and rightly so, synonymous to a day world happens at the speed of thought. If search engine. Simply put, a search engine is nothing but technological advances in the telecommunication a program that searches the World Wide Web for industry have made communication possible even to the keywords entered by the user and returns an output remotest part of the world, the search engines have lend which is nothing but a range of documents where such a hand in ensuring that the requisite information reaches keywords were present.