Bryce Macek Supervisors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acute Limb Ischemia Secondary to Myositis- Induced Compartment Syndrome in a Patient with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Acute limb ischemia secondary to myositis- induced compartment syndrome in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection Russell Lam, MD, Peter H. Lin, MD, Suresh Alankar, MD, Qizhi Yao, MD, PhD, Ruth L. Bush, MD, Changyi Chen, MD, PhD, and Alan B. Lumsden, MD, Houston, Tex Myositis, while uncommon, develops more frequently in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. We report a case of acute lower leg ischemia caused by myositis in such a patient. Urgent four-compartment fasciotomy of the lower leg was performed, which decompressed the compartmental hypertension and reversed the arterial ischemia. This case underscores the importance of recognizing compartment syndrome as a cause of acute limb ischemia. (J Vasc Surg 2003;37:1103-5.) Compartment syndrome results from elevated pressure compartment was firm and tender. Additional pertinent laboratory within an enclosed fascial space, which can occur after studies revealed creatine phosphokinase level of 53,350 U/L; fracture, soft tissue injury, or reperfusion after arterial isch- serum creatinine concentration had increased to 3.5 mg/dL, and emia.1 Other less common causes of compartment syn- WBC count had increased to 18,000 cells/mm3. Venous duplex drome include prolonged limb compression, burns, and scans showed no evidence of deep venous thrombosis in the right extreme exertion.1 Soft tissue infection in the form of lower leg. Pressure was measured in all four compartments of the myositis is a rare cause of compartment syndrome. We right calf and ranged from 55 to 65 mm Hg. -

Evaluation of Suspected Malignant Hyperthermia Events During Anesthesia Frank Schuster*, Stephan Johannsen, Daniel Schneiderbanger and Norbert Roewer

Schuster et al. BMC Anesthesiology 2013, 13:24 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2253/13/24 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Evaluation of suspected malignant hyperthermia events during anesthesia Frank Schuster*, Stephan Johannsen, Daniel Schneiderbanger and Norbert Roewer Abstract Background: Malignant hyperthermia (MH), a metabolic myopathy triggered by volatile anesthetics and depolarizing muscle relaxants, is a potentially lethal complication of general anesthesia in susceptible patients. The implementation of modern inhalation anesthetics that research indicates as less potent trigger substances and the recommended limitations of succinylcholine use, suggests there may be considerable decline of fulminant MH cases. In the presented study, the authors analyzed suspected MH episodes during general anesthesia of patients that were referred to the Wuerzburg MH unit between 2007 and 2011, assuming that MH is still a relevant anesthetic problem in our days. Methods: With approval of the local ethics committee data of patients that underwent muscle biopsy and in vitro contracture test (IVCT) between 2007 and 2011 were analyzed. Only patients with a history of suspected MH crisis were included in the study. The incidents were evaluated retrospectively using anesthetic documentation and medical records. Results: Between 2007 and 2011 a total of 124 patients were tested. 19 of them were referred because of suspected MH events; 7 patients were diagnosed MH-susceptible, 4 MH-equivocal and 8 MH-non-susceptible by IVCT. In a majority of cases masseter spasm after succinylcholine had been the primary symptom. Cardiac arrhythmias and hypercapnia frequently occurred early in the course of events. Interestingly, dantrolene treatment was initiated in a few cases only. -

The Rigid Spine Syndrome-A Myopathy of Uncertain Nosological Position

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.48.9.887 on 1 September 1985. Downloaded from Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1985;48:887-893 The rigid spine syndrome-a myopathy of uncertain nosological position W POEWE,* H WILLEIT,* E SLUGA,t U MAYR* From the University Clinic for Neurology, Innsbruck, * and the Neurological Instiute ofthe University of Vienna, Vienna,t Austria SUMMARY Four patients meeting the clinical criteria of the rigid spine syndrome are presented; they are one girl with a positive family history and three boys. Clinical and histological findings are discussed in relation to the 14 cases of rigid spine syndrome reported in the literature. The delineations of the syndrome from other benign myopathies with early contractures are discussed suggesting that the rigid spine syndrome probably does not represent a single nosological entity. In 1965 Dubowitz' drew attention to a muscular Case reports disorder resembling muscular dystrophy at the time guest. Protected by copyright. of its onset in infancy but of benign and non progres- Since 1978 the authors have had the opportunity to sive nature with the development of only mild examine clinically, electrophysiologically and by muscle weakness. The central clinical feature in this condi- biopsy four cases of a muscle disorder fulfilling the clinical criteria of rigid spine syndrome as described by tion is marked limitation of flexion of the cervical Dubowitz.' The patients were three males and one and dorsolumbar spine with the development of female, whose sister is thought to suffer from the same scoliosis and associated contractures of other joints, disorder. -

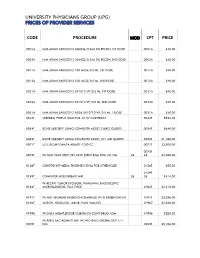

Code Procedure Cpt Price University Physicians Group

UNIVERSITY PHYSICIANS GROUP (UPG) PRICES OF PROVIDER SERVICES CODE PROCEDURE MOD CPT PRICE 0001A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 30MCG/0.3ML DIL RECON 1ST DOSE 0001A $40.00 0002A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 30MCG/0.3ML DIL RECON 2ND DOSE 0002A $40.00 0011A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 100 MCG/0.5 ML 1ST DOSE 0011A $40.00 0012A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 100 MCG/0.5 ML 2ND DOSE 0012A $40.00 0021A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 5X1010 VP/0.5 ML 1ST DOSE 0021A $40.00 0022A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 5X1010 VP/0.5 ML 2ND DOSE 0022A $40.00 0031A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 AD26 5X10^10 VP/0.5 ML 1 DOSE 0031A $40.00 0042T CEREBRAL PERFUS ANALYSIS, CT W/CONTRAST 0042T $954.00 0054T BONE SURGERY USING COMPUTER ASSIST, FLURO GUIDED 0054T $640.00 0055T BONE SURGERY USING COMPUTER ASSIST, CT/ MRI GUIDED 0055T $1,188.00 0071T U/S LEIOMYOMATA ABLATE <200 CC 0071T $2,500.00 0075T 0075T PR TCAT PLMT XTRC VRT CRTD STENT RS&I PRQ 1ST VSL 26 26 $2,208.00 0126T CAROTID INT-MEDIA THICKNESS EVAL FOR ATHERSCLER 0126T $55.00 0159T 0159T COMPUTER AIDED BREAST MRI 26 26 $314.00 PR RECTAL TUMOR EXCISION, TRANSANAL ENDOSCOPIC 0184T MICROSURGICAL, FULL THICK 0184T $2,315.00 0191T PR ANT SEGMENT INSERTION DRAINAGE W/O RESERVOIR INT 0191T $2,396.00 01967 ANESTH, NEURAXIAL LABOR, PLAN VAG DEL 01967 $2,500.00 01996 PR DAILY MGMT,EPIDUR/SUBARACH CONT DRUG ADM 01996 $285.00 PR PERQ SAC AGMNTJ UNI W/WO BALO/MCHNL DEV 1/> 0200T NDL 0200T $5,106.00 PR PERQ SAC AGMNTJ BI W/WO BALO/MCHNL DEV 2/> 0201T NDLS 0201T $9,446.00 PR INJECT PLATELET RICH PLASMA W/IMG 0232T HARVEST/PREPARATOIN 0232T $1,509.00 0234T PR TRANSLUMINAL PERIPHERAL ATHERECTOMY, RENAL -

Compartment Syndrome

Rowan University Rowan Digital Works Stratford Campus Research Day 23rd Annual Research Day May 2nd, 12:00 AM A Case of Atraumatic Posterior Thigh Compartment Syndrome Nailah Mubin Rowan University Brian Katt M.D. Rothman Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/stratford_research_day Part of the Cardiovascular Diseases Commons, Hemic and Lymphatic Diseases Commons, Nephrology Commons, Orthopedics Commons, Pathological Conditions, Signs and Symptoms Commons, and the Surgery Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy - share your thoughts on our feedback form. Mubin, Nailah and Katt, Brian M.D., "A Case of Atraumatic Posterior Thigh Compartment Syndrome" (2019). Stratford Campus Research Day. 47. https://rdw.rowan.edu/stratford_research_day/2019/may2/47 This Poster is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences, Events, and Symposia at Rowan Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Stratford Campus Research Day by an authorized administrator of Rowan Digital Works. A Case of Atraumatic Posterior Thigh Compartment Syndrome Nailah Mubin OMS-III1, Brian Katt MD2 1Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine, 2Brielle Orthopedics at Rothman Institute Introduction Hospital Course Compartment syndrome (CS): intra-compartmental pressures exceed Day 1 4:40am Day 1 5pm Day 4 Day 5 Day 9 Day 12 Day 16 Day 18 Day 19 to a point where arterial, venous and lymphatic circulation of local 1 tissues, muscles and nerves is compromised ER Admit Fasciotomy Cr=7.54 First Closure Pt reports Complete Cr=5.25 Cr=4.09 Discharge 2 • Most common after a traumatic injury . Usually occurs in the leg Dialysis Initiated Attempt increased sensation Closure Cleared by Nephro or forearm and less commonly in the thigh3 • Thigh compartment syndrome (TCS) is rare due to its larger size Surgical Intervention Discussion and more compliant borders. -

ICD-9-CM Coordination and Maintenance Committee Meeting September 28-29, 2006 Diagnosis Agenda

ICD-9-CM Coordination and Maintenance Committee Meeting September 28-29, 2006 Diagnosis Agenda Welcome and announcements Donna Pickett, MPH, RHIA Co-Chair, ICD-9-CM Coordination and Maintenance Committee ICD-9-CM TIMELINE .................................................................................................... 2 Hearing loss, speech, language, and swallowing disorders ........................................... 8 Kyle C. Dennis, Ph.D., CCC-A, FAAA and Dee Adams Nikjeh,Ph.D., CCC-SLP American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Urinary risks factors for bladder cancer ...................................................................... 13 Louis S. Liou, M.D., Ph.D., Abbott Chronic Total Occlusion of Artery of Extremities....................................................... 15 Matt Selmon, M.D., Cordis Osteonecrosis of jaw ....................................................................................................... 17 Vincent DiFabio,M.D., American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons Intraoperative Floppy Iris Syndrome ........................................................................... 18 Priscilla Arnold, M.D., American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery Septic embolism............................................................................................................... 19 Parvovirus B19 ................................................................................................................ 21 Avian Influenza (Bird Flu)............................................................................................ -

4Th Quarter 2001 Medicare a Bulletin

In This Issue... Medicare Guidelines on Telehealth Services Benefit Expansion, Coverage and Conditions for Reimbursement of These Services ............... 5 Medicare eNews Now Available Join Florida Medicare eNews Mailing List to Receive Important News and Information ........ 9 Expansion of Coverage on Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty Coverage Expansion and Claim Processing Instructions for Hospital Inpatient Services ..... 12 Skilled Nursing Facility Consolidated Billing Clarification to Health Insurance Prospective Payment System Coding and Billing Guidelines .............................................................................................................................. 15 Final Medical Review Policies 10060, 55873, 67221, 71250, 74150, 84155, 85007, 88141, 92225, 93303, A0430, G0030,G0104, G0108, J1561, J1745, J9212, and M0302 ...................................... 22 Outpatient Prospective Payment System Update and Changes to the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System ...................... 87 Bulletin Reader Survey Provide your Comments and Feedback on the Medicare Part A Publication and/or our Provider Web Site ................................................................................................................ 103 Features From the Medical Director 3 he Medicare A Bulletin should be shared with all Administrative 4 T health care practitioners and General Information 5 managerial members of the General Coverage 11 provider/supplier staff. Publications issued after End Stage Renal Disease 13 -

Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome of the Lower Leg

UMEÅ UNIVERSITY MEDICAL DISSERTATIONS Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome of the lower leg A novel diagnosis in diabetes mellitus A clinical and morphological study of diabetic and non-diabetic patients David Edmundsson Umeå 2010 From the Department of Surgery and Perioperative Science, Division of Orthopaedics, Umeå University Hospital and Department of Integrative Medical Biology, Section for Anatomy, Umeå University, Umeå, SWEDEN UMEÅ UNIVERSITY MEDICAL DISSERTATIONS New series no: 1334 ISSN 0346-6612 ISBN 978-91-7264-957-6 Department of Surgery and Perioperative Science, Division of Orthopaedics, Umeå University Hospital and Department of Integrative Medical Biology, Section For Anatomy, Umeå University, Umeå, SWEDEN 2 To my wife Thorey and my son Jonathan 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVATIONS..................................................................................................................... 6 POPULÄRVETENSKAPLIG SAMMANFATTNING............................................................. 7 ABSTRACT............................................................................................................................... 8 ORIGINAL PAPERS.................................................................................................................9 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................... 10 COMPARTMENT SYNDROMES.......................................................................................... 10 CHRONIC EXERTIONAL COMPARTMENT -

3Rd Quarter 2002 Medicare B Update

! Highlights In This Issue... Modifier SG— Ambulatory Surgical Center (ASC) Facility Service ..................................................................................................................................... 8 Payment Allowance for Injectable Drugs ................................................................................................................................... 23 New and Revised Local and Focused Medical Review Policies ................................................................................................................................... 29 pdate Administration Simplification Compliance Act (ASCA)—Questions and Answers ................................................................................................................................... 61 Changes to the Standard Paper Remittance Advice U ................................................................................................................................... 69 Medicare Education and Outreach— Calendar of Upcoming Events ................................................................................................................................... 74 Features he Medicare B Update! A Physician’s Focus ..................................... 3 Tshould be shared with all Adminstrative ............................................... 4 health care practitioners and managerial members of the Claims ......................................................... 5 provider/supplier staff. Issues Coverage/Reimbursement .......................... -

(Ptdp-43) Aggregates in the Axial Skeletal Muscle of Patients with Sporadic and Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Matthew D

Cykowski et al. Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2018) 6:28 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-018-0528-y RESEARCH Open Access Phosphorylated TDP-43 (pTDP-43) aggregates in the axial skeletal muscle of patients with sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Matthew D. Cykowski1,2*, Suzanne Z. Powell1,2,3, Joan W. Appel3,4, Anithachristy S. Arumanayagam1, Andreana L. Rivera1,2,3 and Stanley H. Appel2,3,4 Abstract Muscle atrophy with weakness is a core feature of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) that has long been attributed to motor neuron loss alone. However, several studies in ALS patients, and more so in animal models, have challenged this assumption with the latter providing direct evidence that muscle can play an active role in the disease. Here, we examined the possible role of cell autonomous pathology in 148 skeletal muscle samples from 57 ALS patients, identifying phosphorylated TAR DNA-binding protein (pTDP-43) inclusions in the muscle fibers of 19 patients (33.3%) and 24 tissue samples (16.2% of specimens). A muscle group-specific difference was identified with pTDP-43 pathology being significantly more common in axial (paraspinous, diaphragm) than appendicular muscles (P = 0.0087). This pathology was not significantly associated with pertinent clinical, genetic (c9ALS) or nervous system pathologic data, suggesting it is not limited to any particular subgroup of ALS patients. Among 25 non-ALS muscle samples, pTDP-43 inclusions were seen only in the autophagy-related disorder inclusion body myositis (IBM) (n =4),wherethey were more diffuse than in positive ALS samples (P = 0.007). As in IBM samples, pTDP-43 aggregates in ALS were p62/ sequestosome-1-positive, potentially indicating induction of autophagy. -

Muscle Pathology in Total Knee Replacement for Severe Osteoarthritis: a Histochemical and Morphometric Study

Henry Ford Hospital Medical Journal Volume 34 Number 1 Article 7 3-1986 Muscle Pathology in Total Knee Replacement for Severe Osteoarthritis: A Histochemical and Morphometric Study Mark A. Glasberg Janet R. Glasberg Richard E. Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.henryford.com/hfhmedjournal Part of the Life Sciences Commons, Medical Specialties Commons, and the Public Health Commons Recommended Citation Glasberg, Mark A.; Glasberg, Janet R.; and Jones, Richard E. (1986) "Muscle Pathology in Total Knee Replacement for Severe Osteoarthritis: A Histochemical and Morphometric Study," Henry Ford Hospital Medical Journal : Vol. 34 : No. 1 , 37-40. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.henryford.com/hfhmedjournal/vol34/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Henry Ford Health System Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Henry Ford Hospital Medical Journal by an authorized editor of Henry Ford Health System Scholarly Commons. Muscle Pathology in Total Knee Replacement for Severe Osteoarthritis: A Histochemical and Morphometric Study Mark R. Glasberg, MD,* Janet R. Glasberg, BS,* and Richard E. Jones, MD^ We evaluated a series of 12 biopsies from 11 patients with total knee replacements for severe osteoarthritis. All 12 biopsies showed denervation atrophy, while five cases had significant myopathic changes. Morphometric studies indicated a positive atrophy factor (greater than 150) in the type I myofibers in seven cases, the IIA myofibers in nine cases, and the IIB myofibers in all 12 cases. Type I predominance occurred in six cases, HA paucity in two cases, and IIB paucity in two cases. The results indicate that patients with severe osteoarthritis ofthe knee have both significant neuropathic and myopathic changes in quadriceps biopsies. -

Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain Dysfunction in Muscle from Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain Dysfunction in Muscle From Patients With Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Veronica Crugnola, MD; Costanza Lamperti, MD, PhD; Valeria Lucchini, MD; Dario Ronchi, PhD; Lorenzo Peverelli, MD; Alessandro Prelle, MD; Monica Sciacco, MD, PhD; Andreina Bordoni, BS; Elisa Fassone, PhD; Francesco Fortunato, BS; Stefania Corti, MD; Vincenzo Silani, MD; Nereo Bresolin, MD; Salvatore Di Mauro, MD; Giacomo Pietro Comi, MD; Maurizio Moggio, MD Background: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a of 100 fibers), 8 had moderate (5-10 COX-negative fibers major cause of neurological disability and its pathogen- of 100), and 7 had severe (Ͼ10 COX-negative fibers of 100) esis remains elusive despite a multitude of studies. Al- COX deficiency. Spectrophotometric measurement of res- though defects of the mitochondrial respiratory chain have piratory chain activities showed that 3 patients with severe been described in several ALS patients, their pathogenic histochemical COX deficiency also showed combined en- significance is unclear. zyme defects. In 1 patient, COX deficiency worsened in a second biopsy taken 9 months after the first. Among the pa- Objective: To review systematically the muscle biopsy tients with severe COX deficiency, one had a new mutation specimens from patients with typical sporadic ALS to search in the SOD1 gene, another a mutation in the TARDBP gene, for possible mitochondrial oxidative impairment. and a third patient with biochemically confirmed COX de- ficiency had multiple mitochondrial DNA deletions detect- Design: Retrospective histochemical, biochemical, and able by Southern blot analysis. molecular studies of muscle specimens. Conclusions: Our data confirm that the histochemical Setting: Tertiary care university. finding of COX-negative fibers is common in skeletal Subjects: Fifty patients with typical sporadic ALS (mean muscle from patients with sporadic ALS.